A Record of Retaliation for Doing Exactly What I Was Trained to Do

Who I Am, How This Began, and Why It Matters Beyond Me

By Aaron Knapp

Investigative Journalist

Founder and Editor, Unplugged with Knapp

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

My name is Aaron Christopher Knapp. I am a licensed social worker in the State of Ohio and an investigative journalist. I am not a lifelong Ohio resident. I came to this state to attend The Ohio State University, was educated here, trained here, licensed here, and like many who pass through Ohio’s public institutions, chose to remain and build a career rooted in the communities my education was designed to serve.

I was trained under the curriculum of The Ohio State University College of Social Work and under the ethical, legal, and professional frameworks that govern social work practice in Ohio. That training was neither abstract nor aspirational. It was explicit, operational, and repeatedly reinforced through coursework, supervision, field education, and licensure standards. Social workers are taught that their professional responsibility does not stop at service delivery. It extends to systems, institutions, and power. We are trained to identify harm, to document it, and to act when policies, practices, or officials place people at risk.

One principle was emphasized above all others. When a social worker observes misconduct, abuse of authority, civil rights violations, or systemic harm, they are not merely permitted to speak. They are ethically obligated to do so. Silence in those circumstances is not neutrality. Silence is complicity.

This obligation is not limited to clinical settings. It applies to macro practice, community advocacy, policy engagement, and institutional accountability. The profession explicitly recognizes that many of the harms faced by vulnerable people are not accidental. They are produced by systems that resist scrutiny and punish those who challenge them. Social workers are trained to expect that resistance, to document carefully, and to persist lawfully.

Before any of this became personal, I encountered a moment of reflection that now frames everything that followed. I heard a story on NPR that centered on a difficult truth. Ethical principles only matter when they cost something. Otherwise they are simply words repeated in classrooms and codes of conduct. The story argued that sometimes good people are placed in positions where doing the right thing carries real risk, and that those moments are not chosen. They arrive unannounced, often early, often unexpectedly, and they force a decision about who you are going to be.

Aaron Knapp

Not long after, I was presented with that decision.

My involvement with the Lorain Police Department did not begin as a personal conflict or a professional dispute. It began as a response to a public incident that raised constitutional, ethical, and systemic concerns. I engaged with that incident exactly as I had been trained to do. I reviewed publicly available information. I asked questions through lawful channels. I submitted public records requests under Ohio law. I raised concerns openly, transparently, and on the record about government conduct that affected the public and vulnerable individuals.

I did not act anonymously. I did not act recklessly. I did not act for personal gain. I attached my name, my credentials, and my reputation to what I said because accountability requires ownership. I believed explainers about constitutional limits, records access, and public trust were not optional additions to public service. I believed they were the core.

The response to that engagement was not dialogue or correction. It was escalation.

In my first year on the job, the Chief of Police questioned my education, attacked my licensure, and initiated actions that placed my career and professional standing at risk. Rather than addressing the substance of the concerns raised, the response reframed ethical advocacy as misconduct and transparency as threat. At that moment, the abstract lesson I had absorbed during my training became concrete. I had to decide whether my ethics were conditional or real.

I understood the stakes. I understood the unspoken alternative. I could disengage, recast the issue as personal rather than systemic, and quietly retreat to preserve my own stability. Many professionals do. Systems rely on that calculation. They do not need to silence everyone. They only need to make an example of a few.

I chose not to retreat.

I chose to act in accordance with my training, my licensure, and the ethical obligations that define the social work profession. What followed was not an isolated disagreement, a misunderstanding, or a clash of personalities. It was a sustained pattern of retaliation, exclusion, and professional pressure that extended beyond a single agency and into interconnected systems.

This matters because the issue documented here is not whether one social worker experienced retaliation. The issue is what happens to an entire profession, and to public accountability itself, when ethical training collides with institutional self protection. When professionals learn that speaking up results in surveillance, isolation, and career harm, silence becomes the rational choice. Ethics become performative. Oversight becomes hollow.

Ohio promotes a culture of “see something, say something.” Social work education reinforces that mandate. Public records law is designed to facilitate it. Constitutional protections exist to safeguard it.

Yet my experience demonstrates a contradictory lesson. When you see something and say something, you become the problem. When you document, you are labeled disruptive. When you persist, you are marginalized. When you refuse to go away, the system waits you out.

This record exists so that this pattern can be examined in full, not as a personal grievance, but as a systemic failure. It exists so that those charged with oversight can evaluate not only what was done, but how much was done verbally, informally, and off the record. It exists because ethical training should not function as a professional trap.

I did exactly what I was trained to do. If that choice now carries consequences, then the problem is not the training. It is the system that punishes its use.

Aaron Knapp, LSW

The Ethical Obligation That Set Everything in Motion

What Social Work Actually Teaches and Why It Exists

Social work as a profession does not train people to look away from harm. It exists precisely because harm is often produced, maintained, or concealed by systems that function without sufficient accountability. From its earliest foundations, social work has recognized that individual suffering is frequently the predictable outcome of institutional decisions, policy failures, and abuses of authority. As a result, the profession is structured not only around service delivery, but around intervention at the systems level.

Macro practice is not an optional extension of social work, nor is it a personal preference exercised at the discretion of individual practitioners. It is a recognized, protected, and essential function of the profession. Social workers are trained to operate across micro, mezzo, and macro levels because ethical practice requires attention to both individual impact and systemic cause. Limiting professional responsibility to direct service while ignoring institutional harm is expressly contrary to the values the profession is built upon.

Reporting misconduct, challenging unlawful or unconstitutional policies, insisting on transparency, and advocating for communities that lack political or institutional power are not deviations from social work ethics. They are the direct application of those ethics. The profession’s codes, educational curricula, and licensure standards emphasize that social workers have a duty to promote social justice, protect human dignity, and challenge structures that perpetuate inequity or abuse. These obligations do not disappear when the source of harm is a government agency or a public official.

I was trained that when systems harm people, documentation is the first ethical response. When officials misuse authority, raising concerns through lawful and appropriate channels is not optional. When agencies close ranks to avoid scrutiny, persistence becomes a professional obligation, not a personal choice. At every stage, the method matters. Ethical advocacy does not involve harassment, fabrication, coercion, or retaliation. It relies on evidence, records, law, and transparency. It seeks correction, not retribution.

This framework exists because social workers are uniquely positioned to observe patterns others may dismiss or normalize. We work in proximity to vulnerable populations, within institutions that exercise power over people’s lives, and alongside systems that often resist external oversight. The profession therefore anticipates institutional discomfort and backlash when ethical obligations are exercised. That possibility is not treated as a reason to remain silent. It is treated as a known risk that must be navigated with care, professionalism, and documentation.

The ethical standards governing social work are not aspirational statements meant to be honored only when convenient. They are operational mandates designed to function under pressure. They assume that ethical action may provoke resistance, hostility, or attempts to discredit the professional raising concerns. That is precisely why the profession emphasizes adherence to law, reliance on records, and the maintenance of a clear evidentiary trail.

My actions were taken within that framework. I documented what I observed. I raised concerns through lawful channels. I relied on public records, statutory rights, and established professional standards. I did not act impulsively or anonymously. I did not seek attention or personal advantage. I did exactly what I was trained to do, in the manner I was trained to do it.

If adherence to those ethical obligations is now treated as misconduct, then the issue is not an individual practitioner’s judgment. It is a systemic failure to tolerate the very accountability mechanisms that social work, as a profession, is designed to provide.

The City and County Response Was Not Correction, It Was Containment

Social Media, Public Records, Juvenile Court Materials, and the First Retaliation

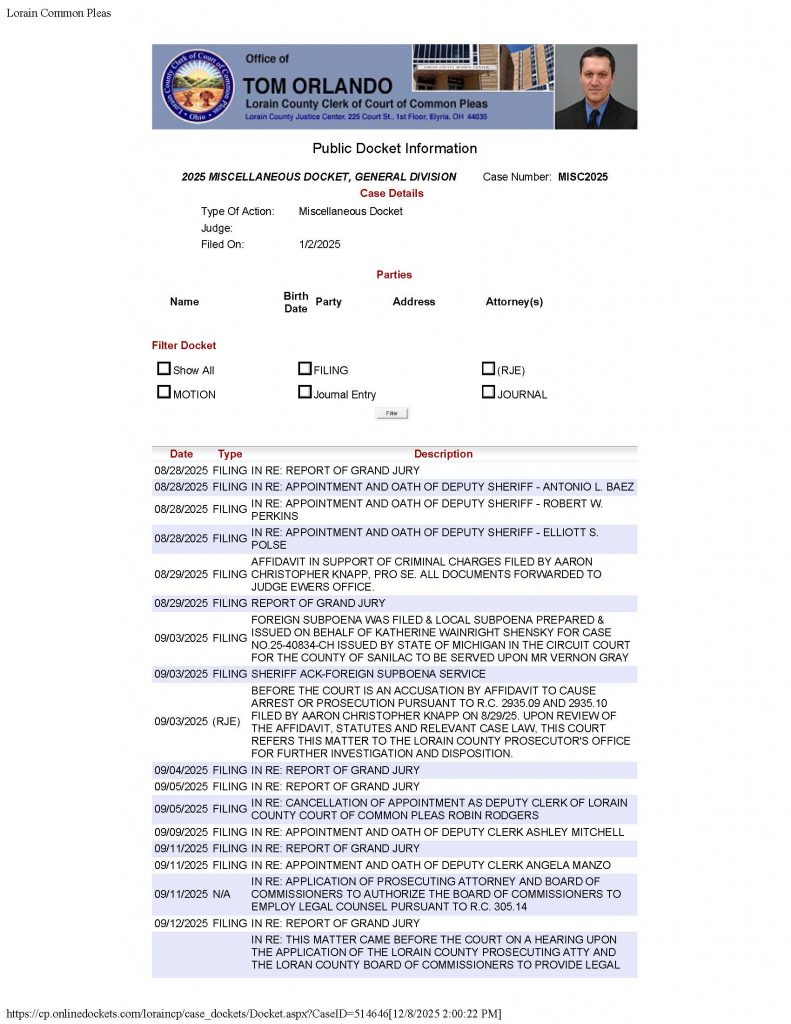

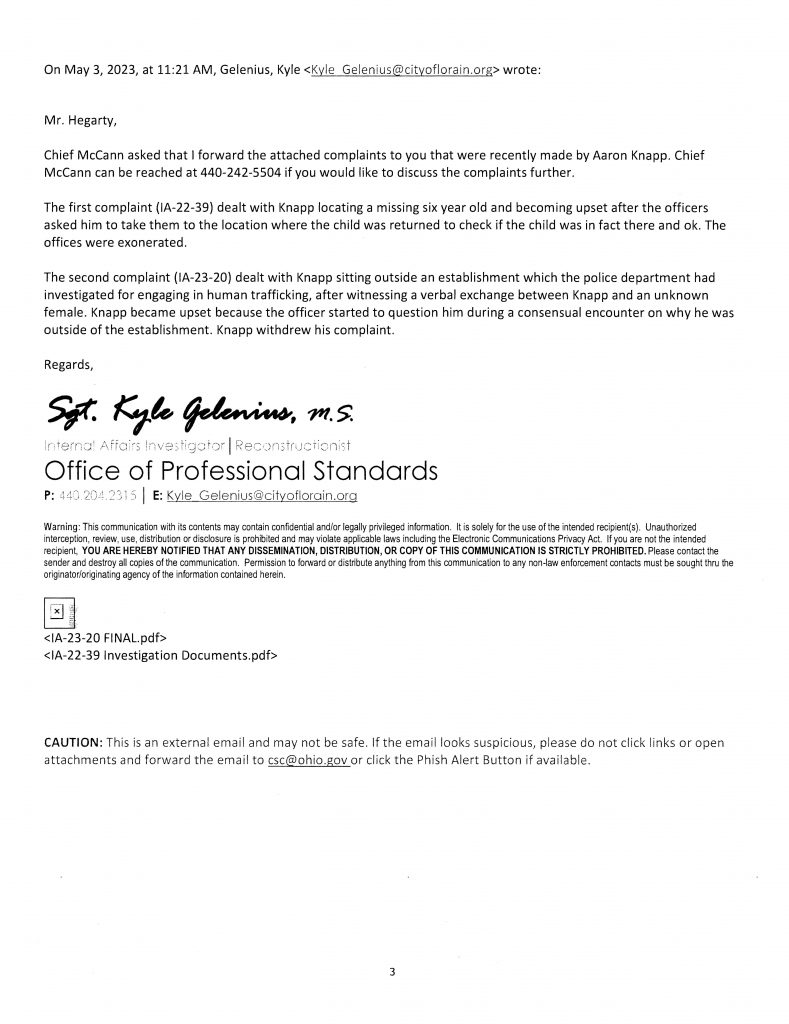

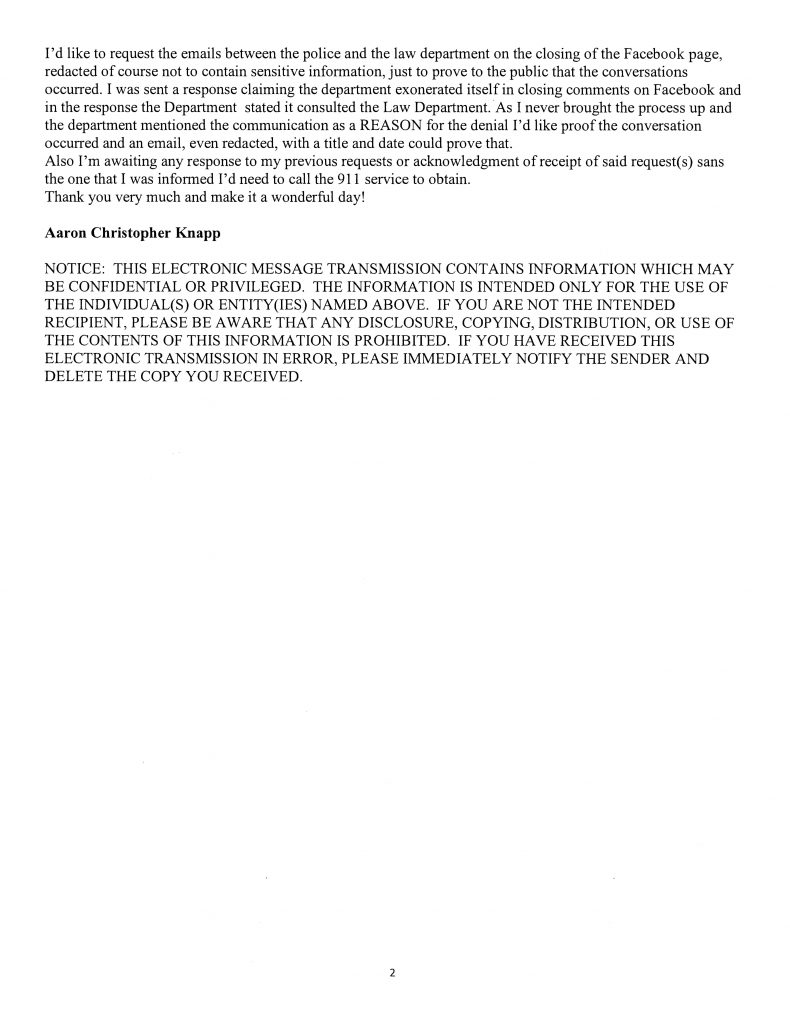

The first major flashpoint in this matter involved the Lorain Police Department and its response to public scrutiny following a police incident at 126 West 27th Street. As criticism increased, the department disabled public comment on its official social media platforms. These were not private accounts or discretionary communication channels. They were government operated forums used to publish official statements, disseminate information, and shape public narrative on matters of law enforcement and public concern.

The restriction of comments was selective and context driven. Posts unrelated to the incident or favorable to the department continued to permit interaction, while posts drawing criticism did not. This distinction is legally significant. Government operated social media pages that invite public engagement function as designated public forums and are subject to First Amendment constraints. That framework was well established at the time and formed the basis of the concerns I raised.

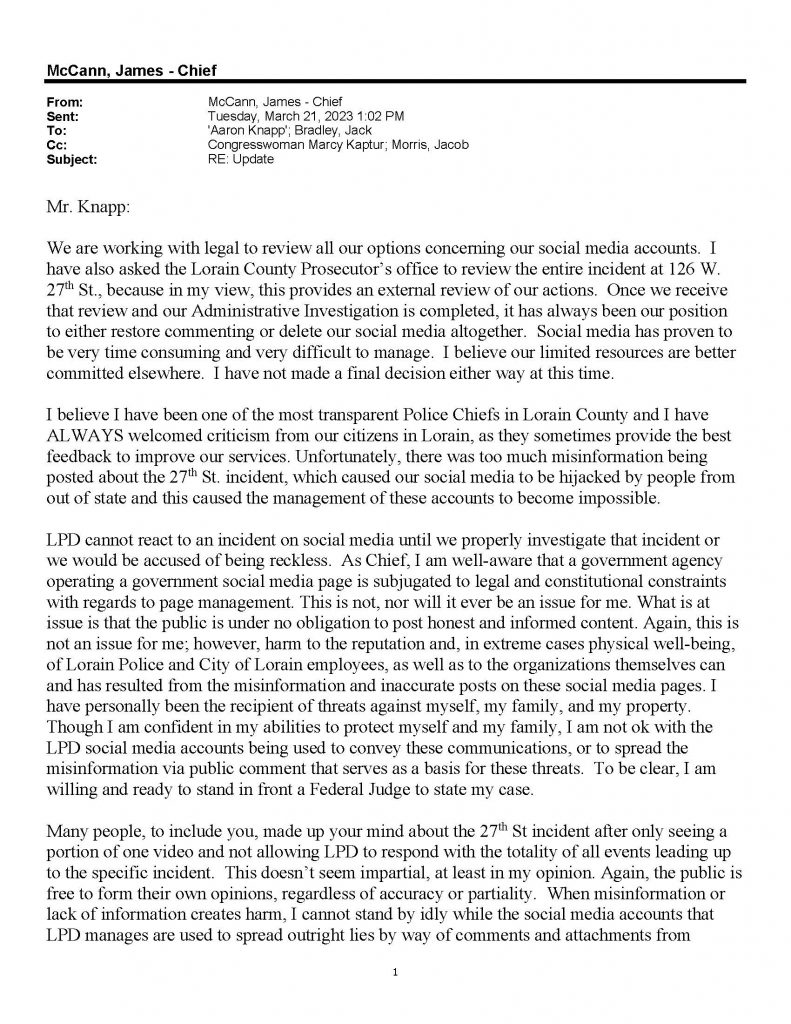

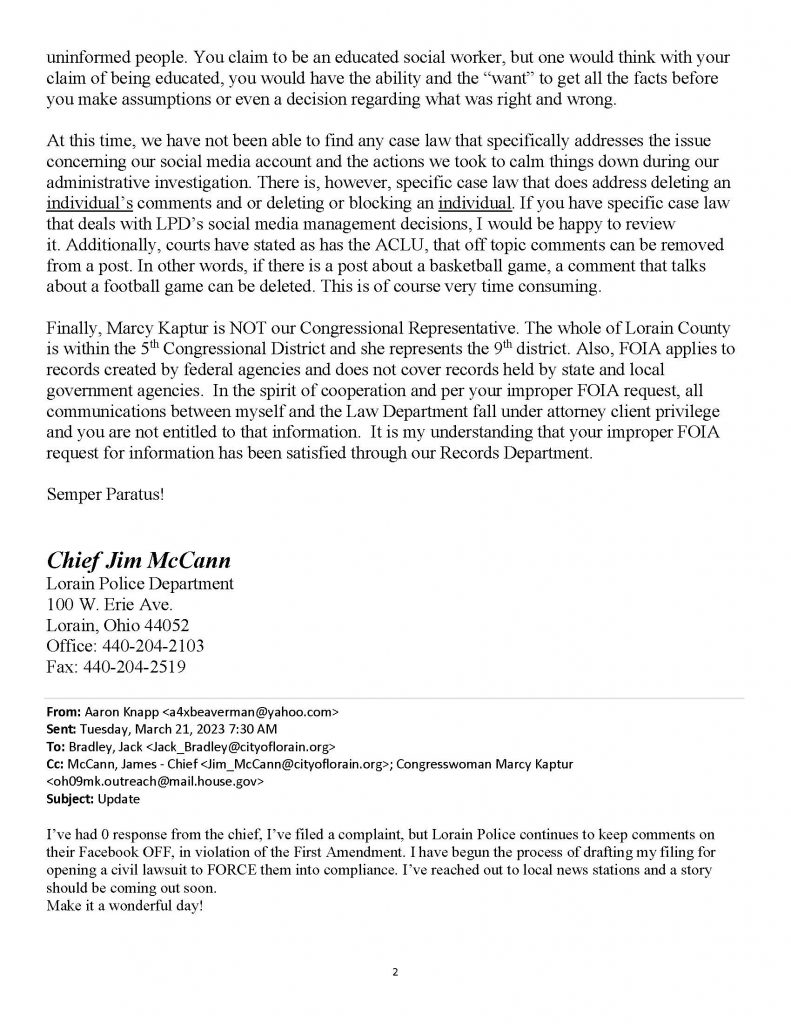

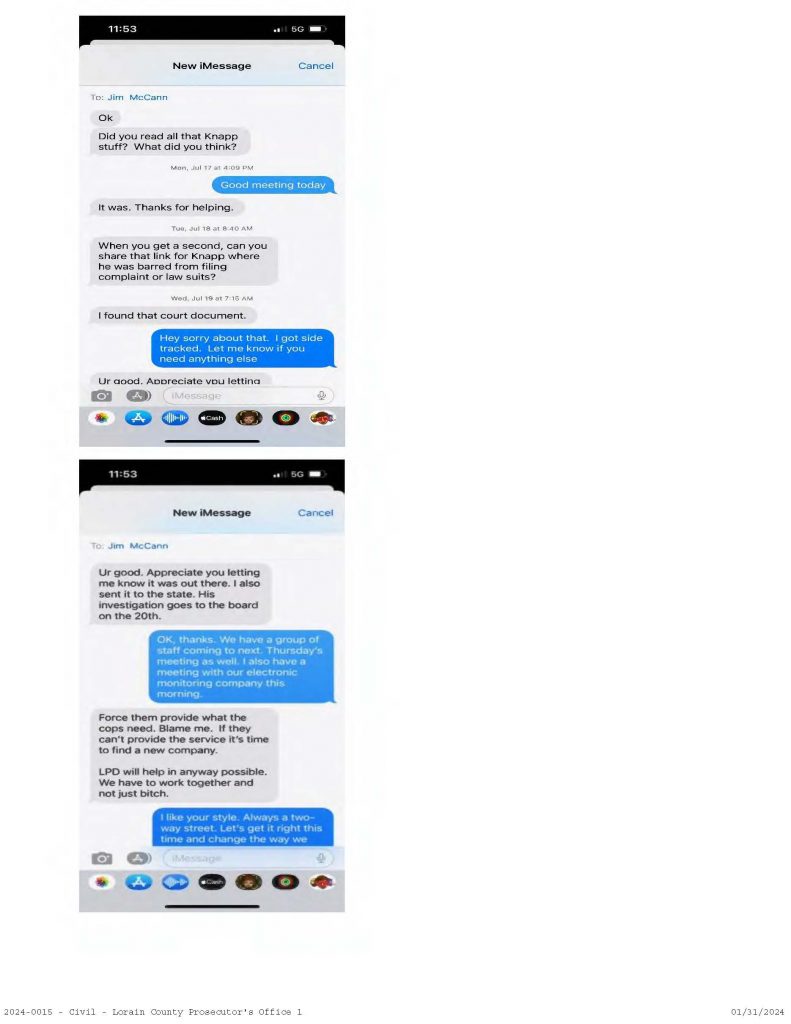

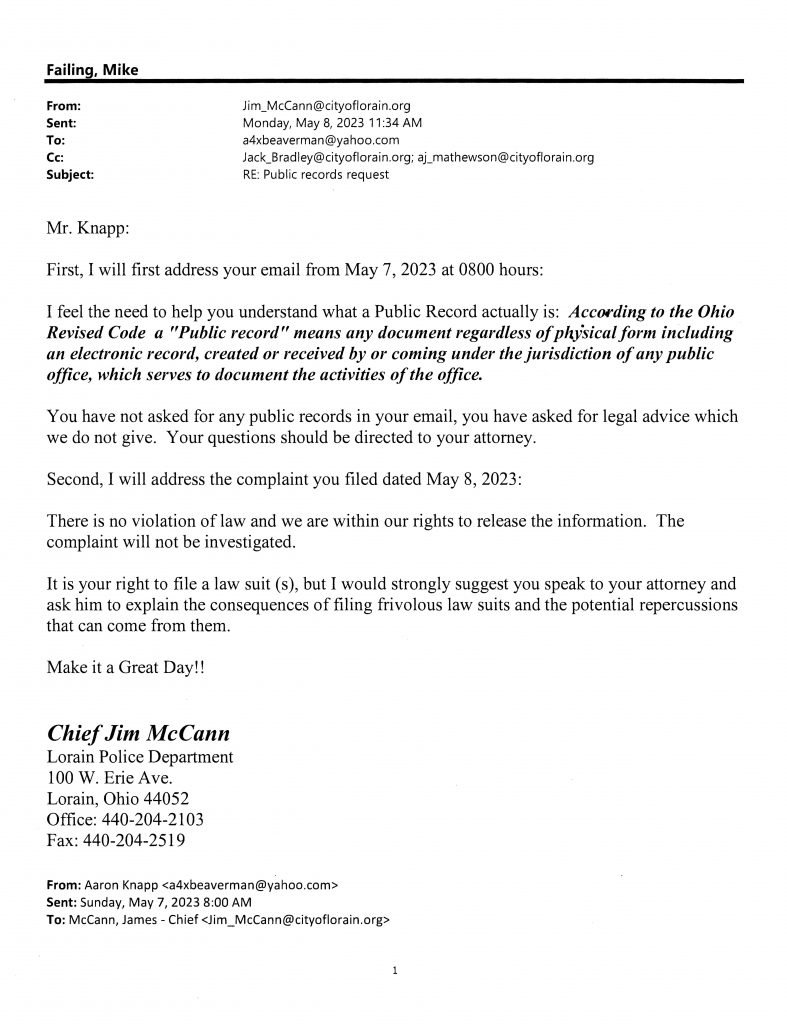

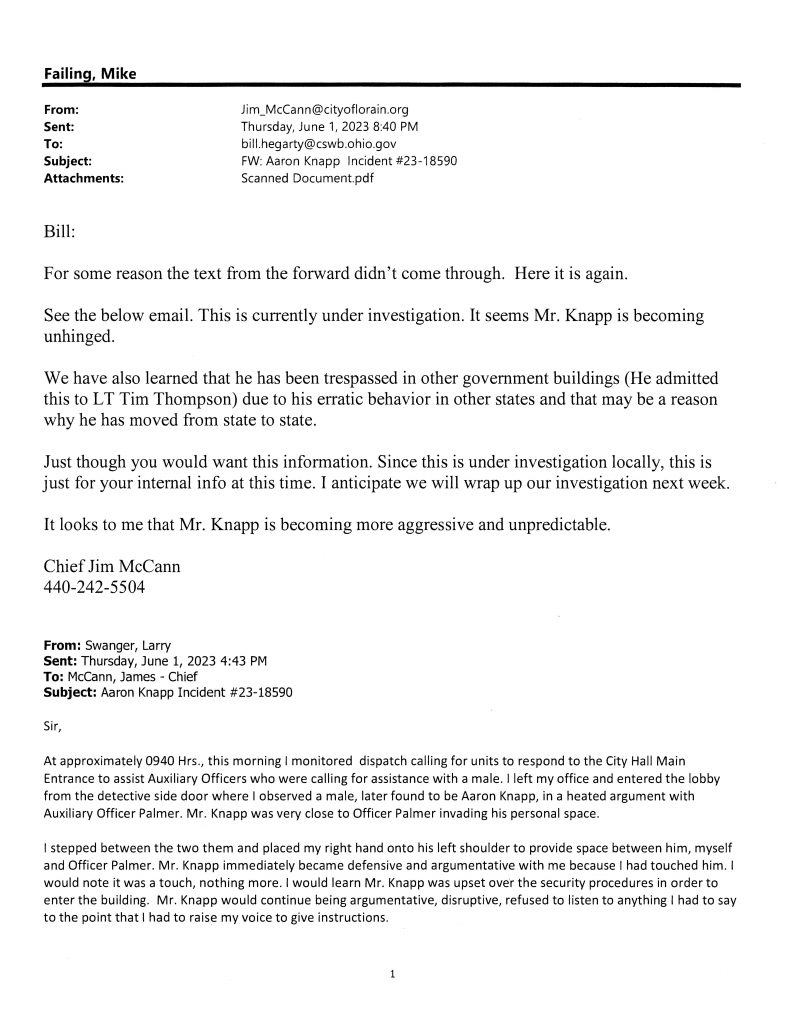

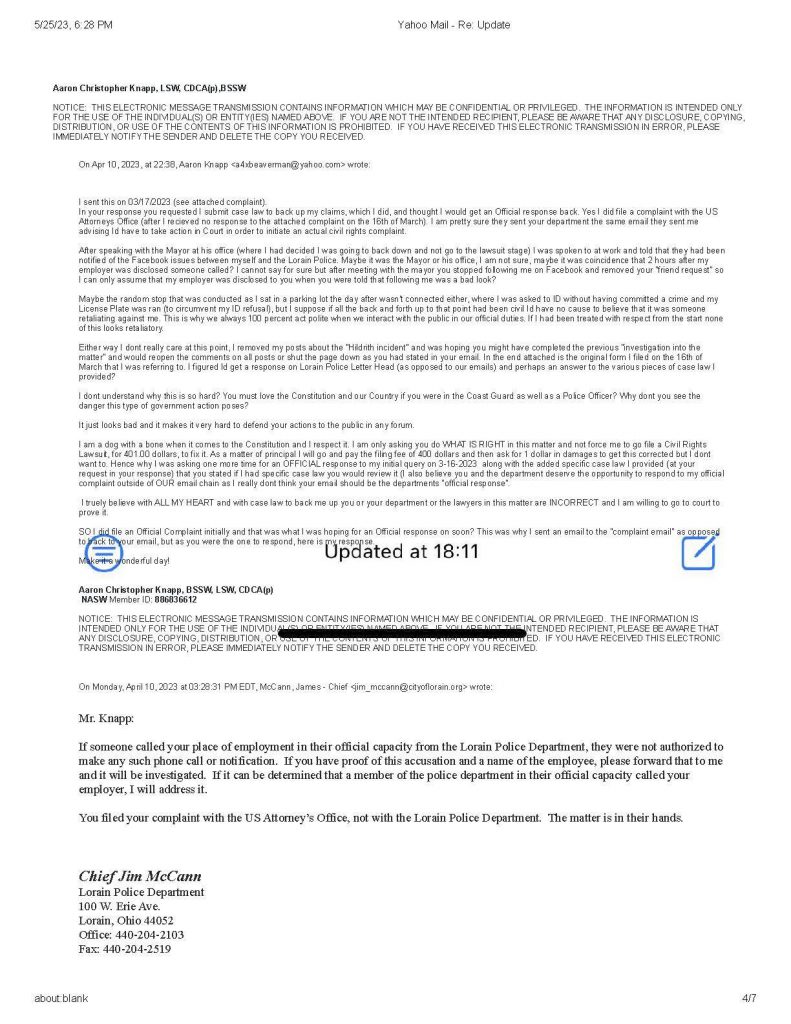

When comments were disabled, I raised the constitutional implications openly and directly. I did not do so casually or rhetorically. At the express request of Police Chief James McCann, I prepared and submitted a structured, written response citing relevant case law and articulating the governing First Amendment standards applicable to government operated social media. That response was sent directly to Chief McCann after he specifically asked me to provide legal authority addressing the department’s actions.

The department did not dispute that constitutional limits applied. Chief McCann acknowledged in writing that a government agency operating a government social media page is subject to constitutional constraints. Yet despite that acknowledgment, the restriction remained in place. No written legal determination was issued. No formal policy was adopted. No response was provided addressing the case law I submitted. The action continued without articulated legal justification.

Instead of engaging the substance of the constitutional analysis, the response shifted in tone and focus.

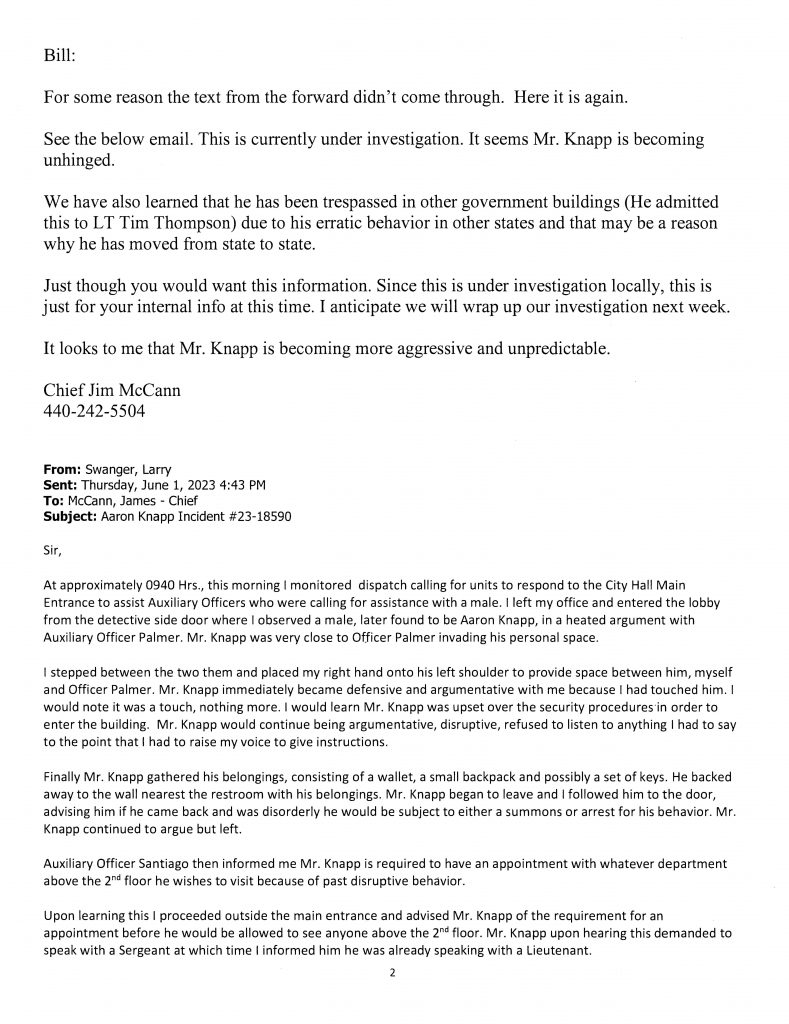

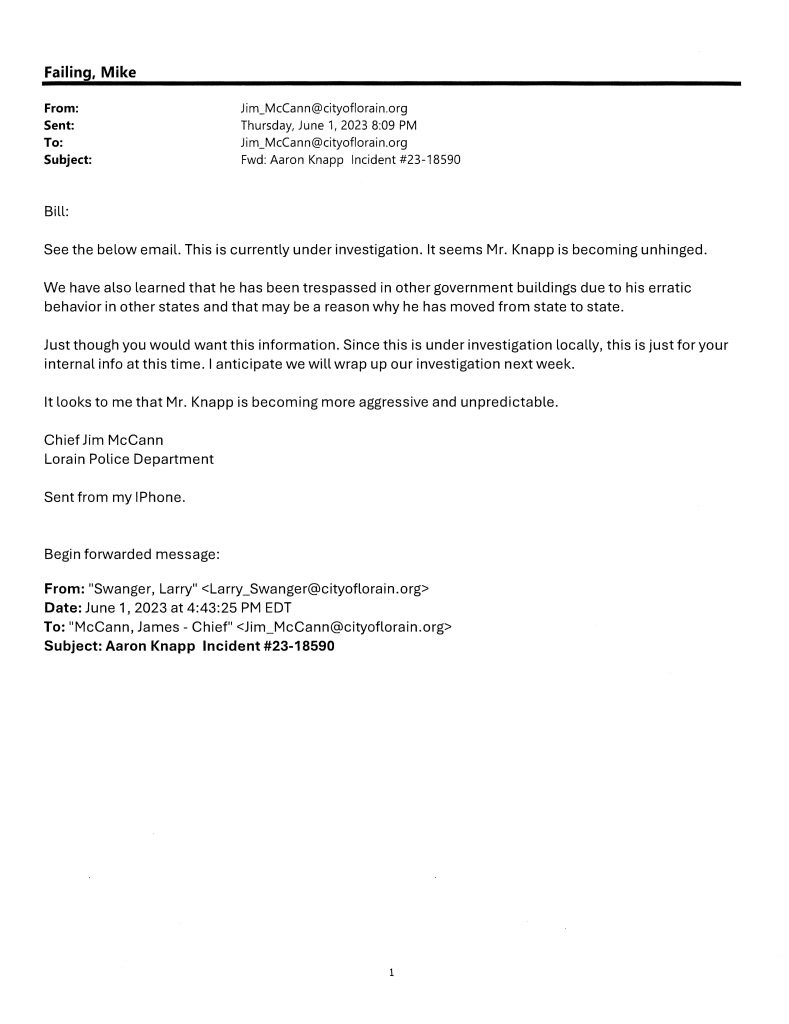

Chief McCann accused the public of spreading misinformation without defining the term or identifying objective criteria.

He asserted that threats had been made against himself and his family, but did not distinguish between criminal threats and protected speech, nor did he provide documentation tying those assertions to the comments being restricted. Criticism was dismissed while transparency was simultaneously claimed.

At the same time, his communications challenged my education and professional credibility rather than addressing the legal issue raised. My training, licensure, and professional role were invoked not as context, but as a basis for questioning my motives and judgment. This marked the first instance in which my professional identity as a social worker became a target rather than a qualification.

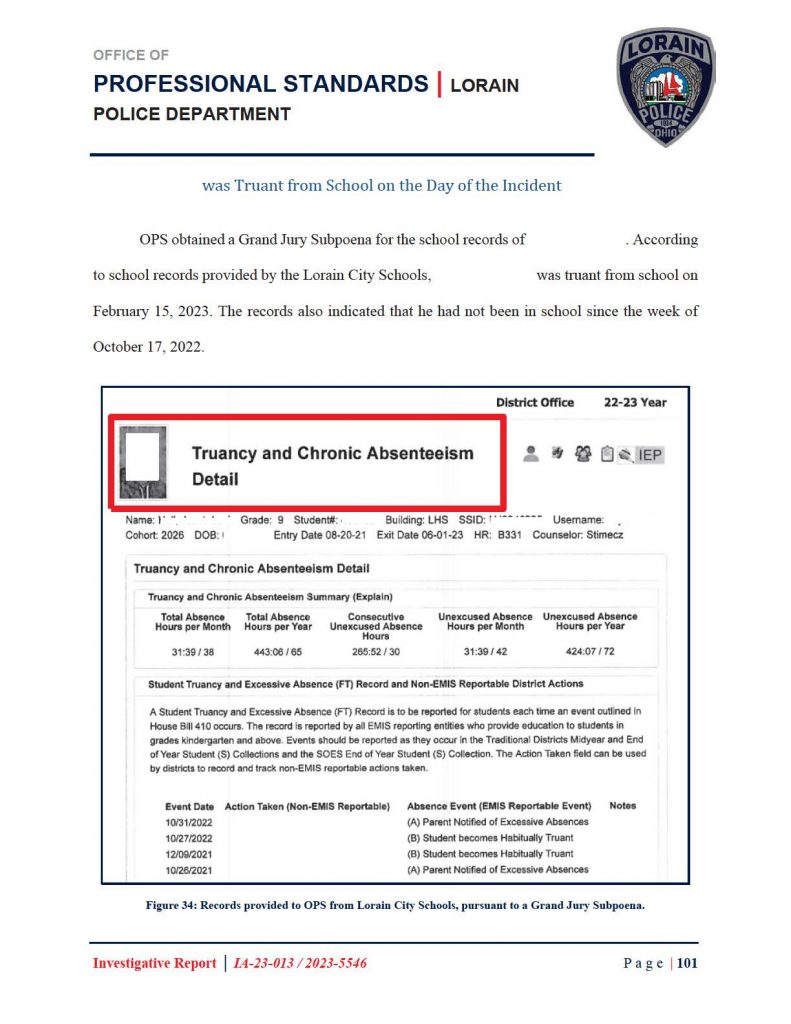

What significantly deepened the gravity of this episode was the department’s handling of juvenile related materials in the same public forum. As part of its public response to the incident, the Lorain Police Department posted and maintained documents originating from the Juvenile Court system. These materials included sensitive juvenile records, including letters that juveniles were assisted in writing to victims as part of court related processes.

At the time, I was contracted within the juvenile court system. I understood, firsthand and professionally, the strict legal and ethical protections governing juvenile records. Those protections exist precisely because disclosure can cause lasting harm to minors and undermine the rehabilitative goals of the juvenile justice system. Despite this, the documents remained publicly accessible on the department’s website for approximately three years.

When concerns were raised about the presence of juvenile court materials online, the response was not prompt correction. Instead, the continued publication suggested an institutional indifference to the protections owed to minors. In Chief McCann’s public statements addressing the controversy, responsibility appeared to be shifted outward, at times framing the issue in a way that implicitly placed blame on the judiciary or judicial process itself for the content of the records.

The contrast is instructive. Public speech criticizing police conduct was restricted in the name of safety and order. Juvenile records deserving heightened protection were left publicly available.

One category of expression was treated as dangerous. The other, involving minors, was treated as expendable.

What Followed Was Escalation, Not Resolution

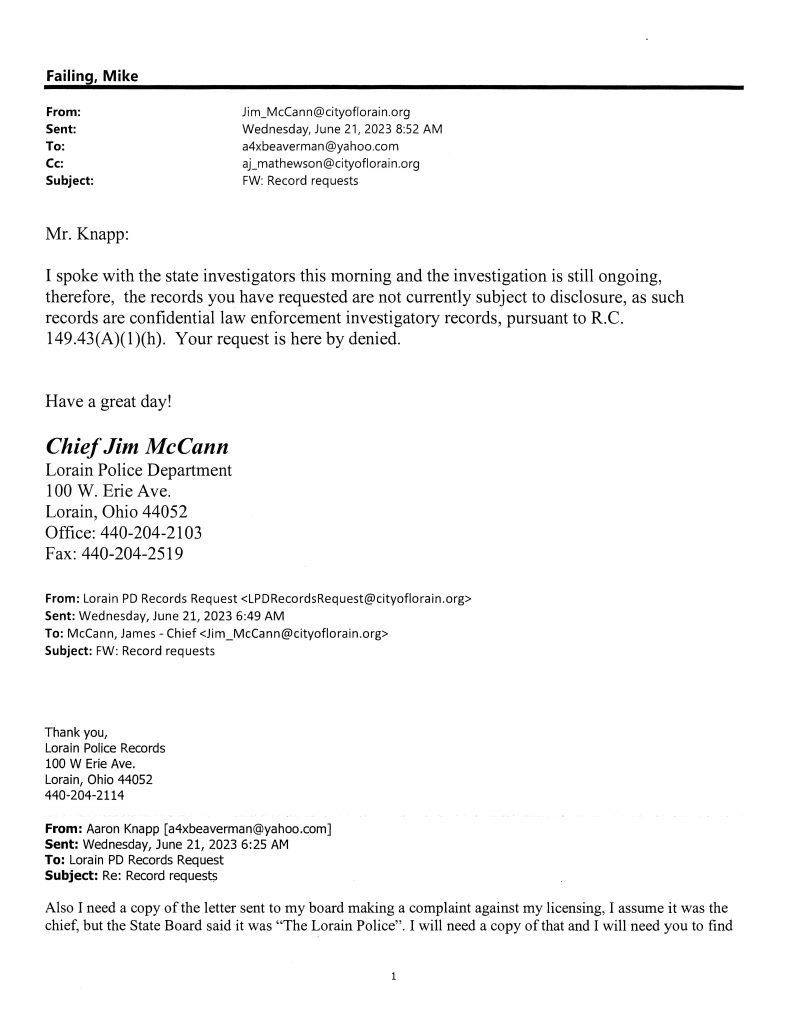

Board Communications, Court Interference, and the Expansion of Retaliation Beyond City Hall

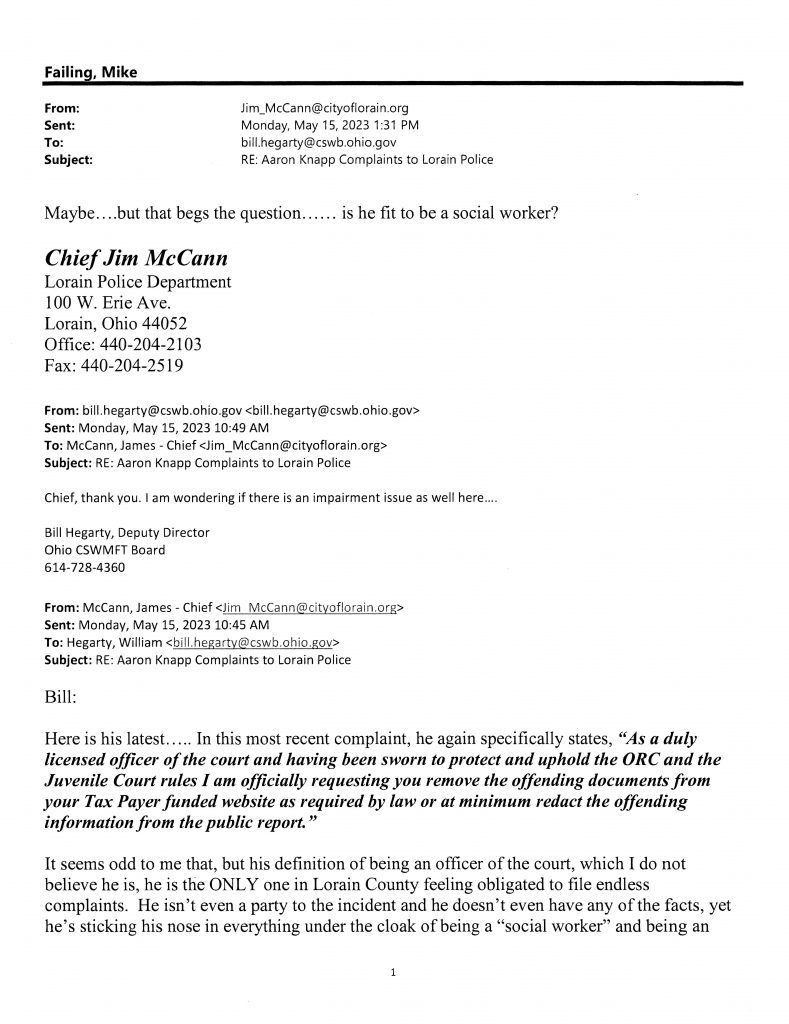

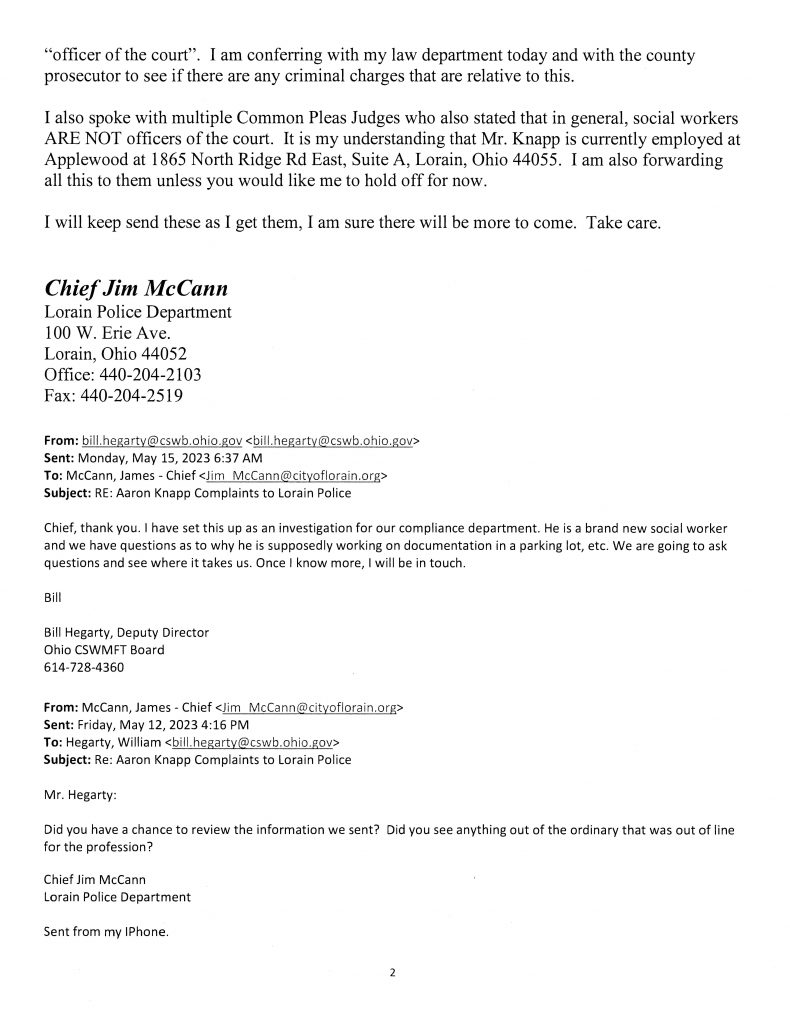

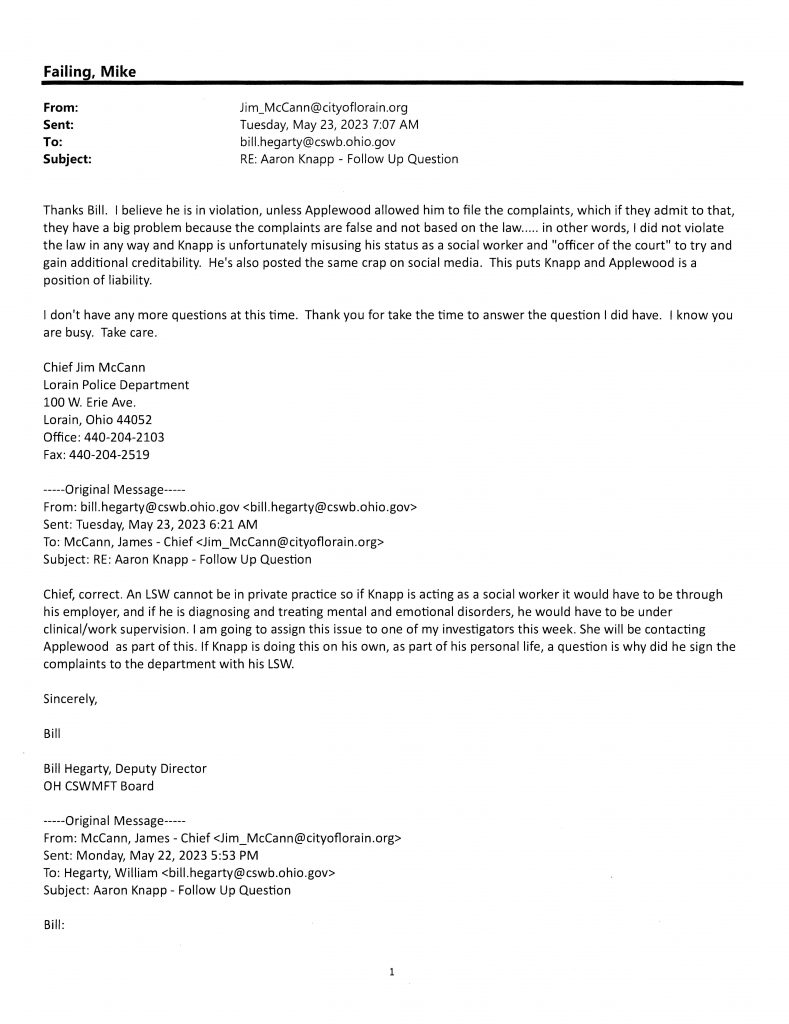

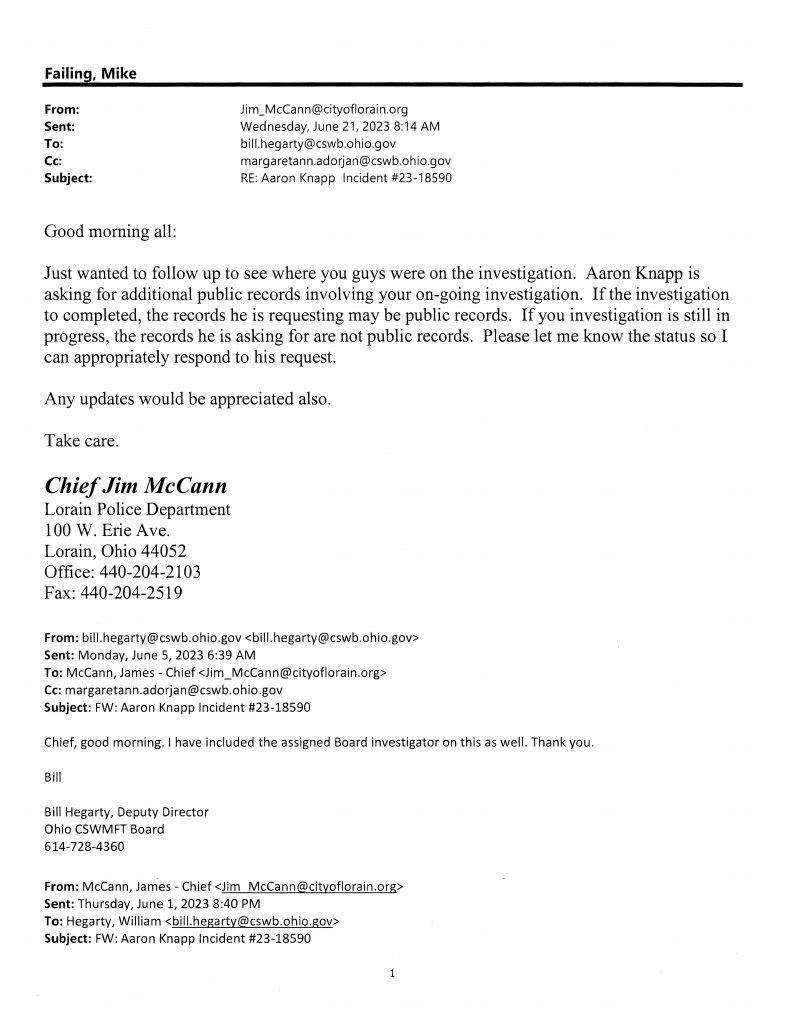

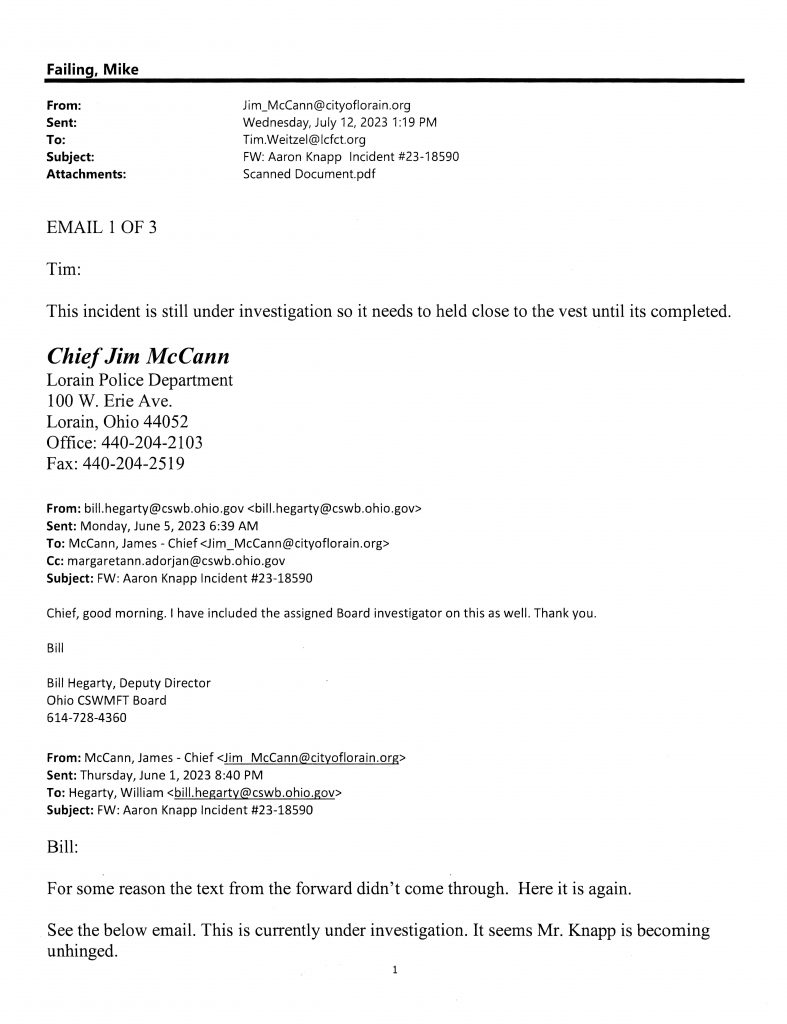

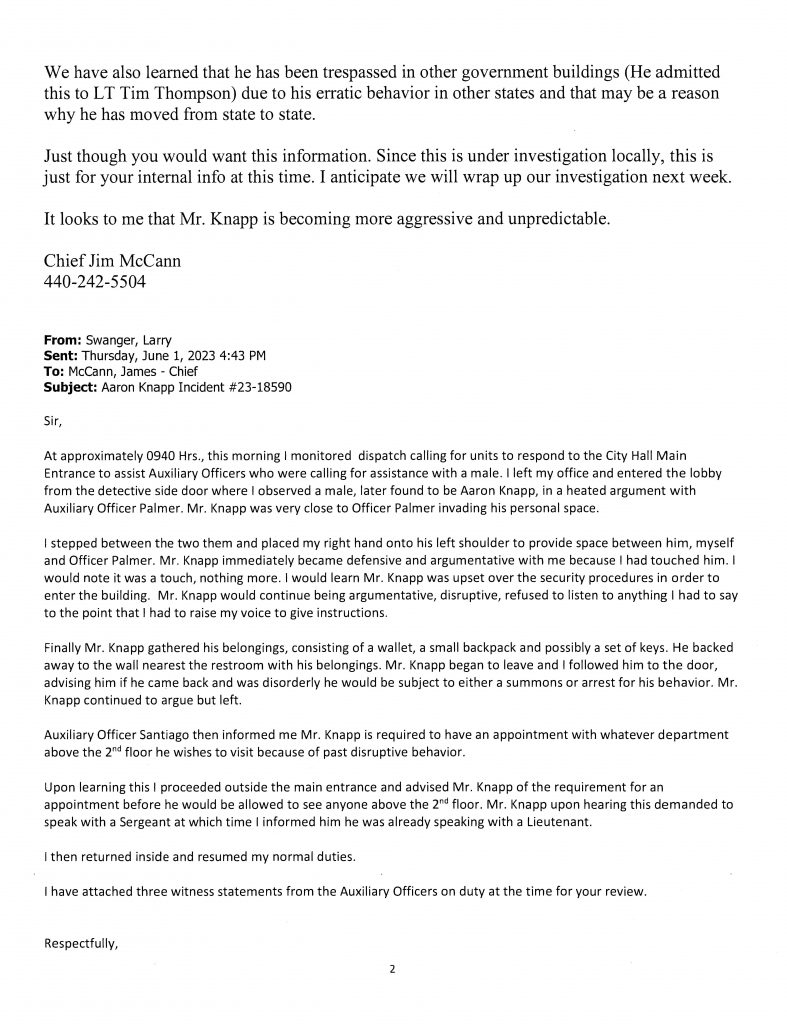

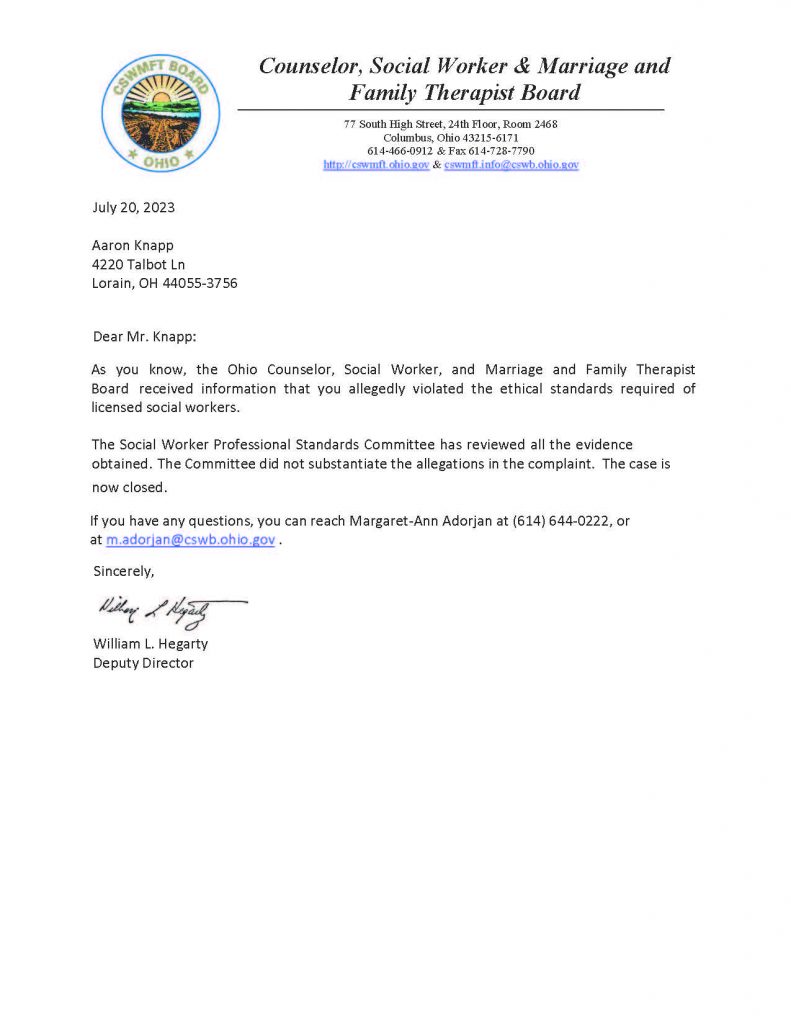

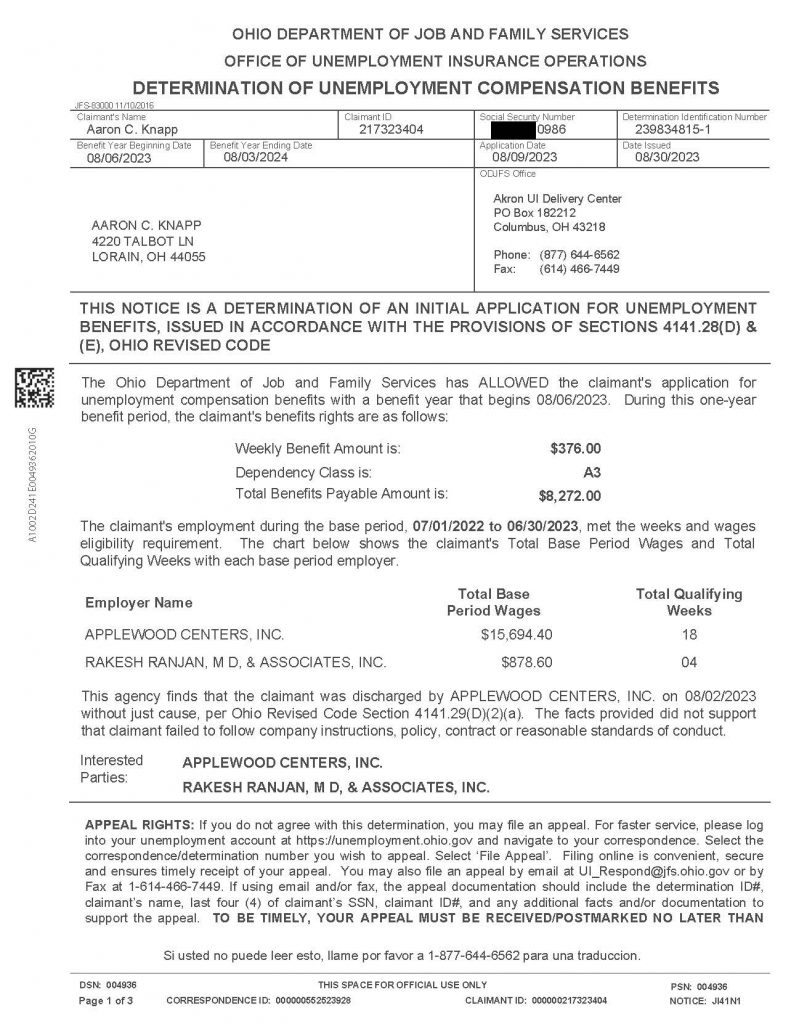

After the social media dispute and the submission of case law directly to Chief James McCann, the matter did not de escalate. Instead, it expanded outward into areas that directly implicated my professional licensure, my standing within the juvenile court system, and my ability to continue working in my chosen field.

Rather than addressing the constitutional and records based concerns on their merits, communications began appearing that reframed the issue as one of my professionalism rather than government conduct. This shift was not incidental. It marked a transition from disagreement to containment through credentialed harm.

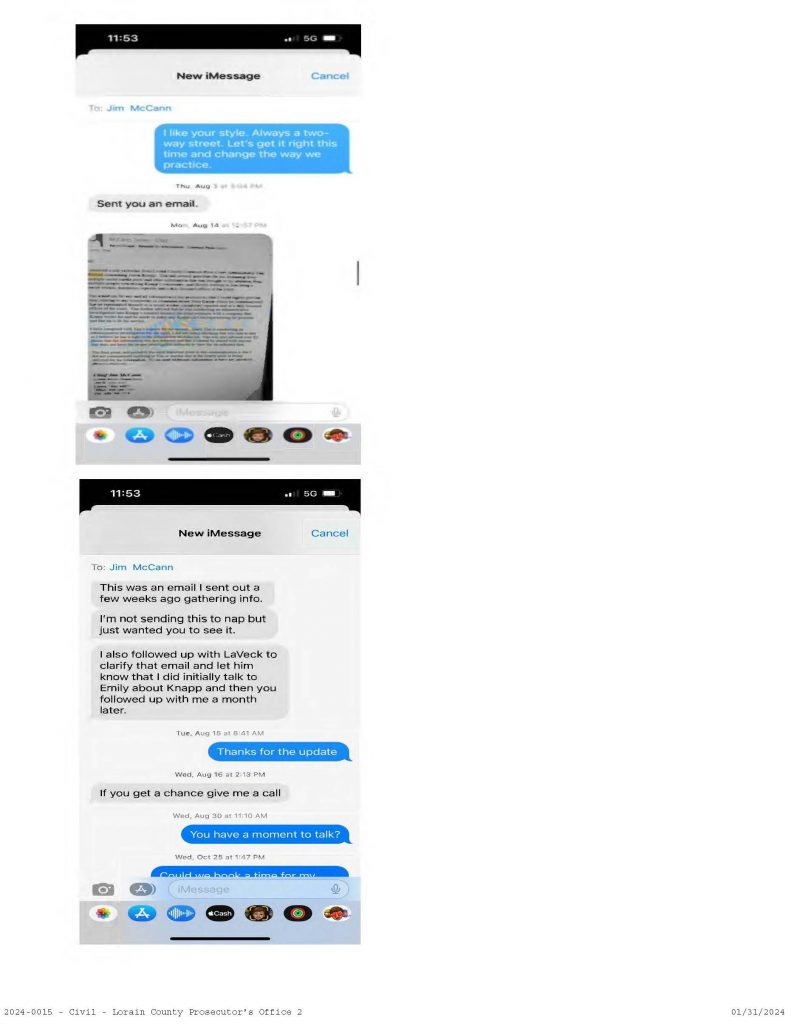

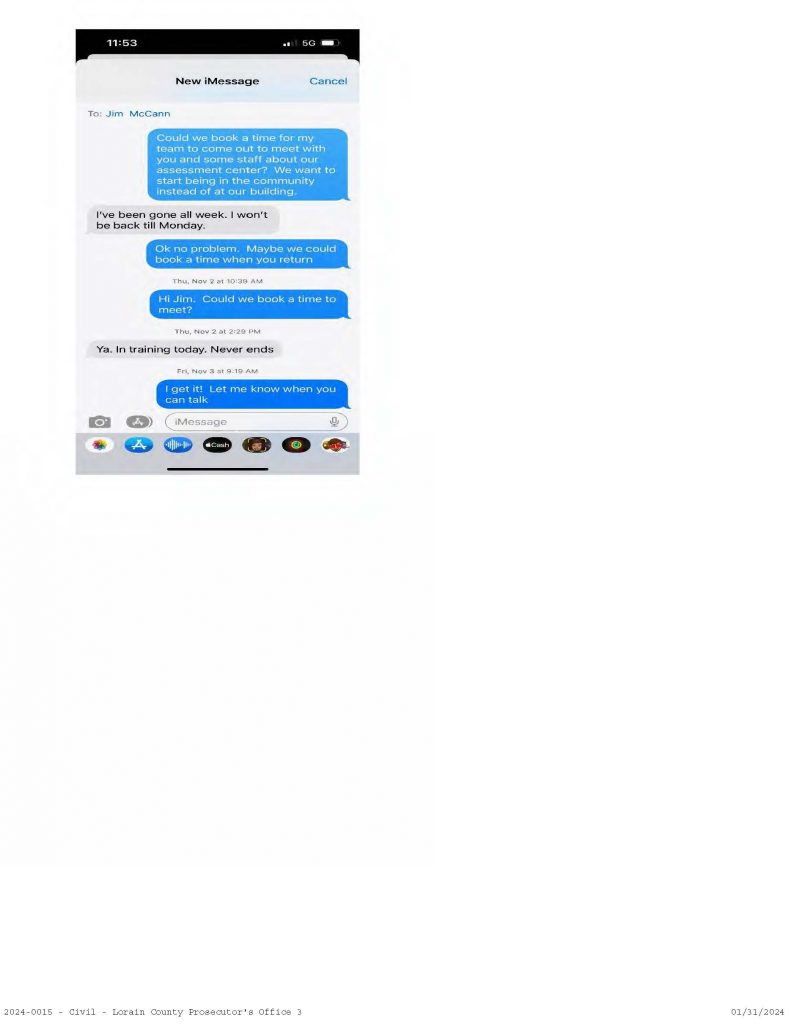

Emails were sent to external actors referencing my license, my mental state, and my role within the juvenile court system. These communications did not occur in a vacuum and they were not routed through neutral oversight channels. They were directed toward individuals and institutions with the practical power to disrupt my employment and reputation without triggering immediate judicial review.

Among those contacted was the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist Board, the regulatory body governing my professional license. The framing of those communications was not that of a routine ethics inquiry supported by objective findings. Instead, they conveyed concerns about my conduct that closely mirrored the narrative used to dismiss my constitutional and public records advocacy.

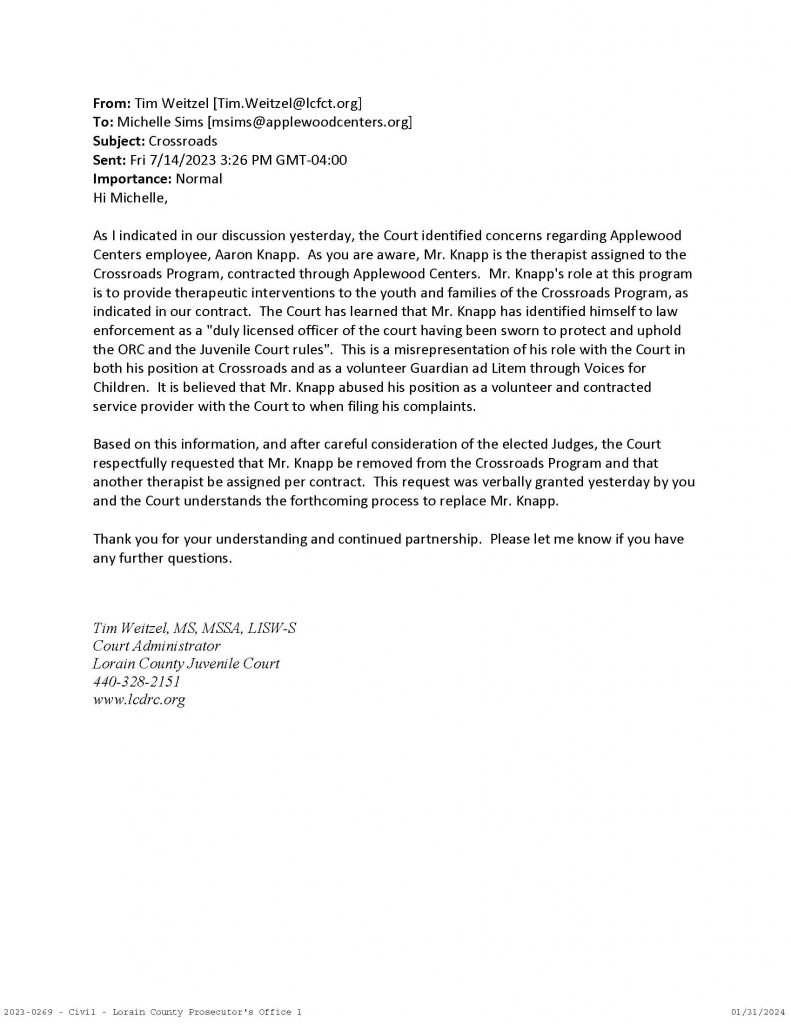

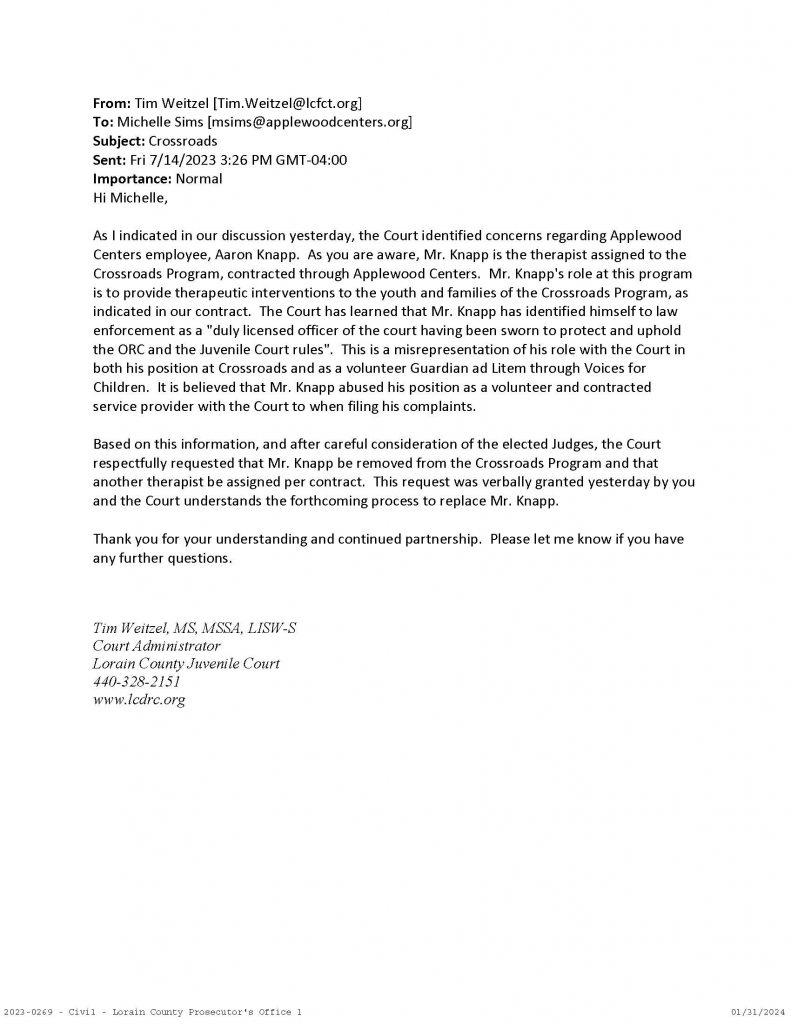

At the same time, communications were sent to individuals within the juvenile court system, including Tim Weitzel, with whom I had no disciplinary history and no prior professional conflict. These messages referenced my involvement in the social media dispute and public criticism of the police department, despite those matters having no legitimate nexus to my contractual performance within the juvenile court.

This distinction is critical. Advocacy directed at police conduct and government transparency is not misconduct under social work ethics. It is protected activity. Yet the effect of these communications was to reframe protected conduct as a professional liability, creating pressure points that did not require formal charges or findings to produce harm.

The practical impact was immediate and chilling. Access narrowed. Professional relationships cooled without explanation. No written allegation was provided. No hearing was scheduled. No corrective plan was proposed. The consequences occurred without process.

This is how retaliation operates when it is sophisticated. Institutions communicate sideways. They plant concerns. They circulate character narratives. They allow uncertainty to do the work of exclusion.

Court Controlled Status Was Stated, Then Quietly Scrubbed

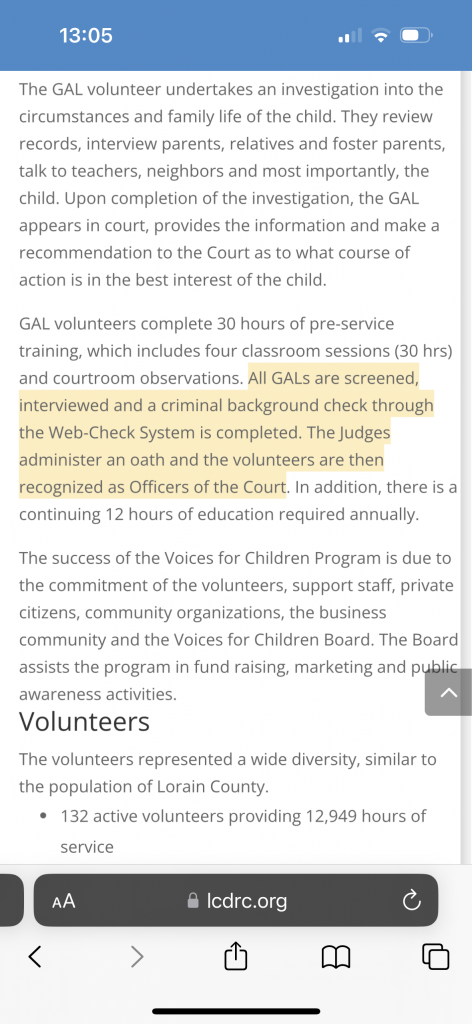

A key evidentiary piece that belongs in this record, and that changes how any neutral reader understands later exclusion, is the juvenile court related website language you preserved in a screenshot. The language is not ambiguous and it is not casual marketing copy. It describes a process that includes screening, interviewing, background checks, a judge administered oath, and then states that the volunteers are “recognized as Officers of the Court.”

That description matters because it is the court, speaking in plain language to the public, describing how it conceptualizes the role. It is an institutional representation of status and function. It directly supports the claim that the GAL role is not a hobby relationship with staff but a court governed role rooted in oath, screening, and expectations of integrity.

It matters even more because you have documented that the county later changed the website and removed the “Officers of the Court” language. When an institution removes clarifying language after conflict arises, the question becomes why. If the language was inaccurate, one would expect an explanation, a correction notice, or a replacement description that clarifies the precise status. If instead the language is simply scrubbed, what is left is the appearance of retroactive recharacterization.

In the context of this record, this screenshot becomes the anchor for one of my strongest arguments. This was not merely a community volunteer position you lost for interpersonal reasons. It was a court associated role described by the court as involving oath and recognition, and the later handling of your access lacked the basic attributes of due process and transparency that should attach to anything the court itself is publicly describing as “Officer of the Court” adjacent.

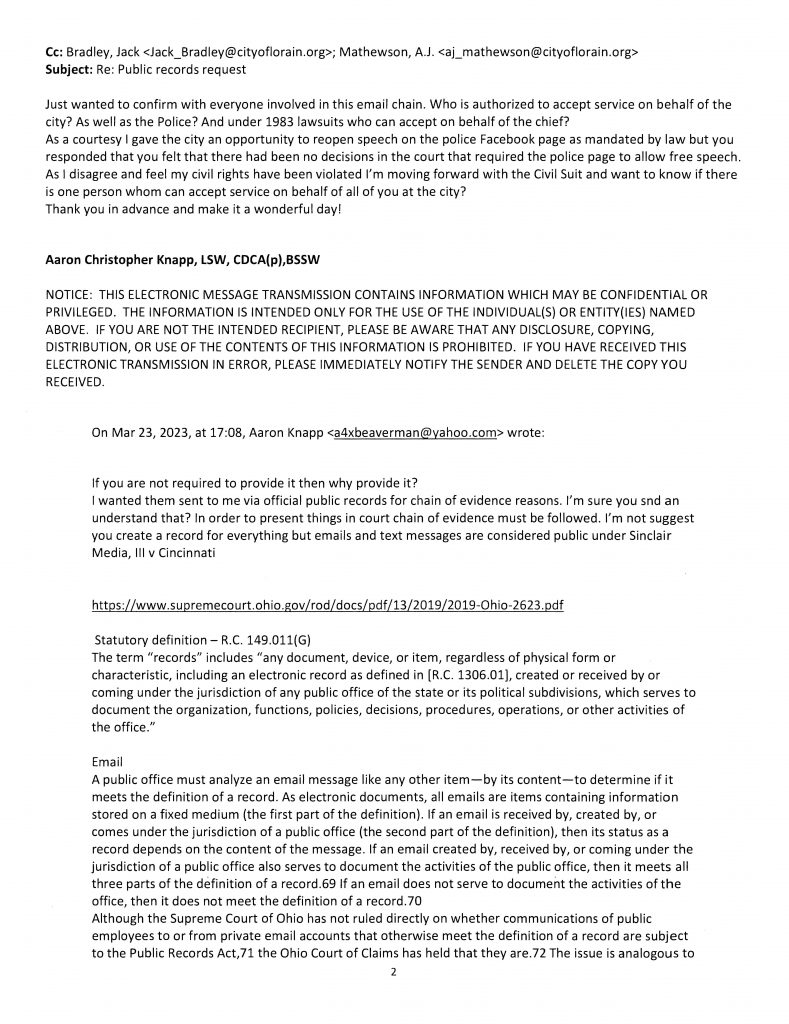

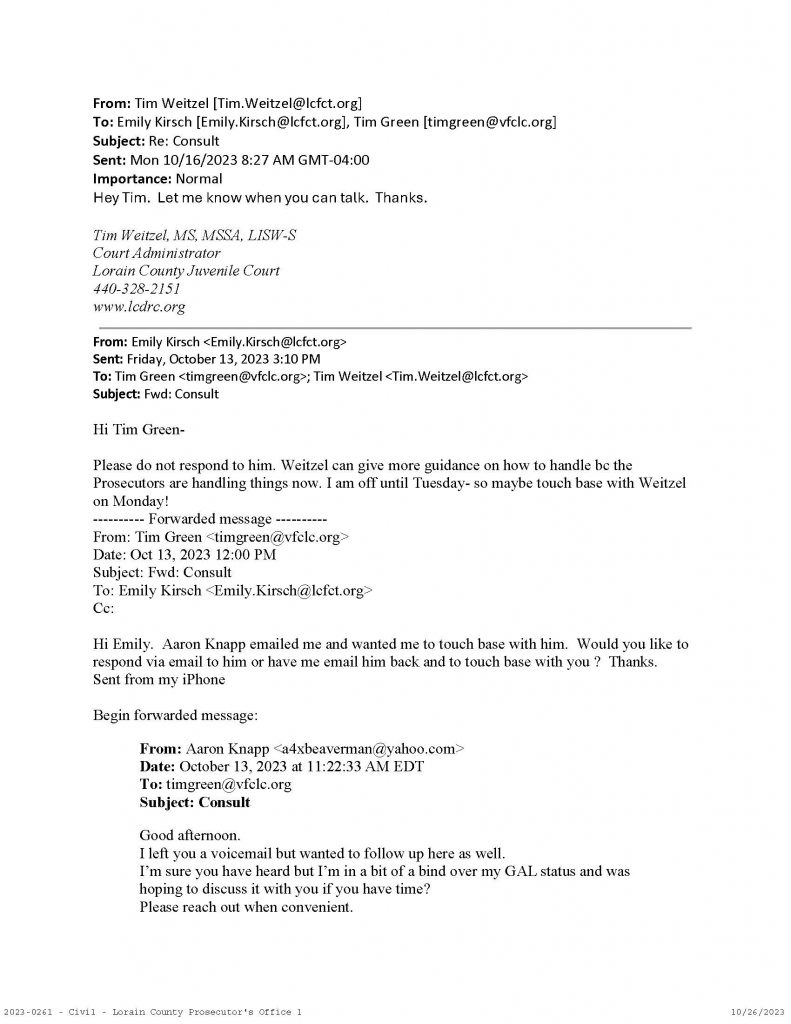

The Email Record Shows Gatekeeping and Prosecutor Control

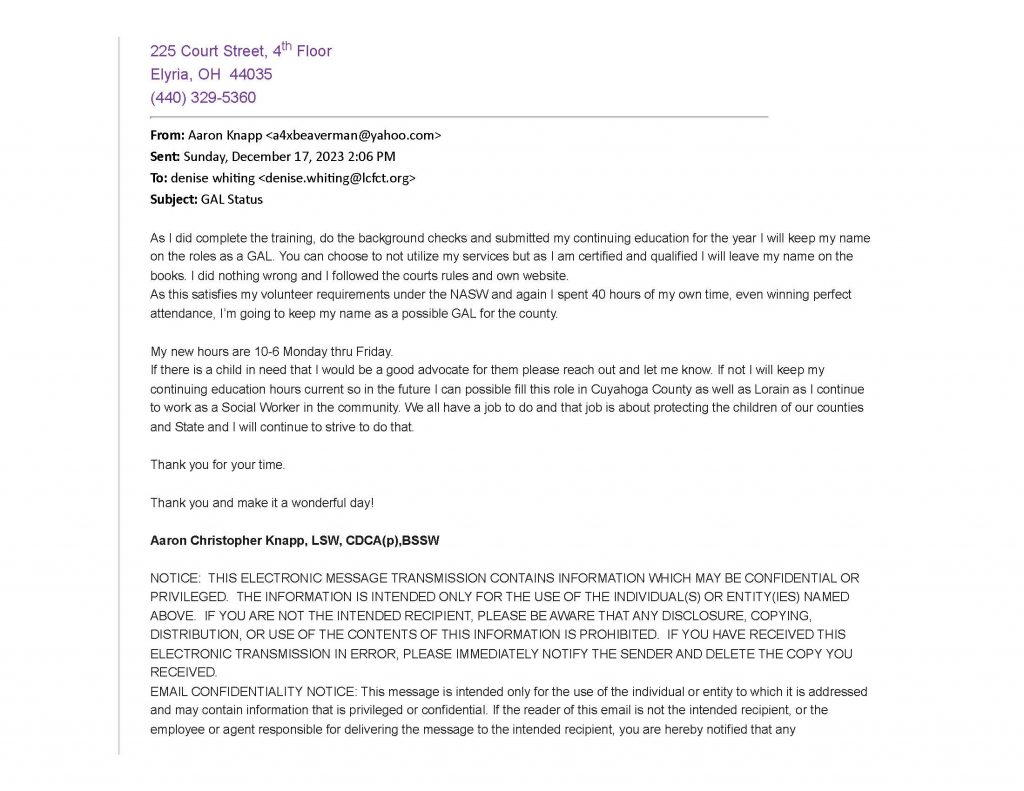

Another addition that shifts the story from narrative to demonstrable mechanism is the email chain Below involving Tim Weitzel, Emily Kirsch, and Tim Green, with the underlying email from me requesting a consult about your GAL status.

The structure of the chain is simple, and that simplicity is the point. I reached out politely, asked for a consult, and explicitly framed it as a practical bind over my GAL status. A third party then asked internal leadership how to respond, and the answer from within that ecosystem was effectively, do not respond, and Weitzel can give more guidance because “the Prosecutors are handling things now.”

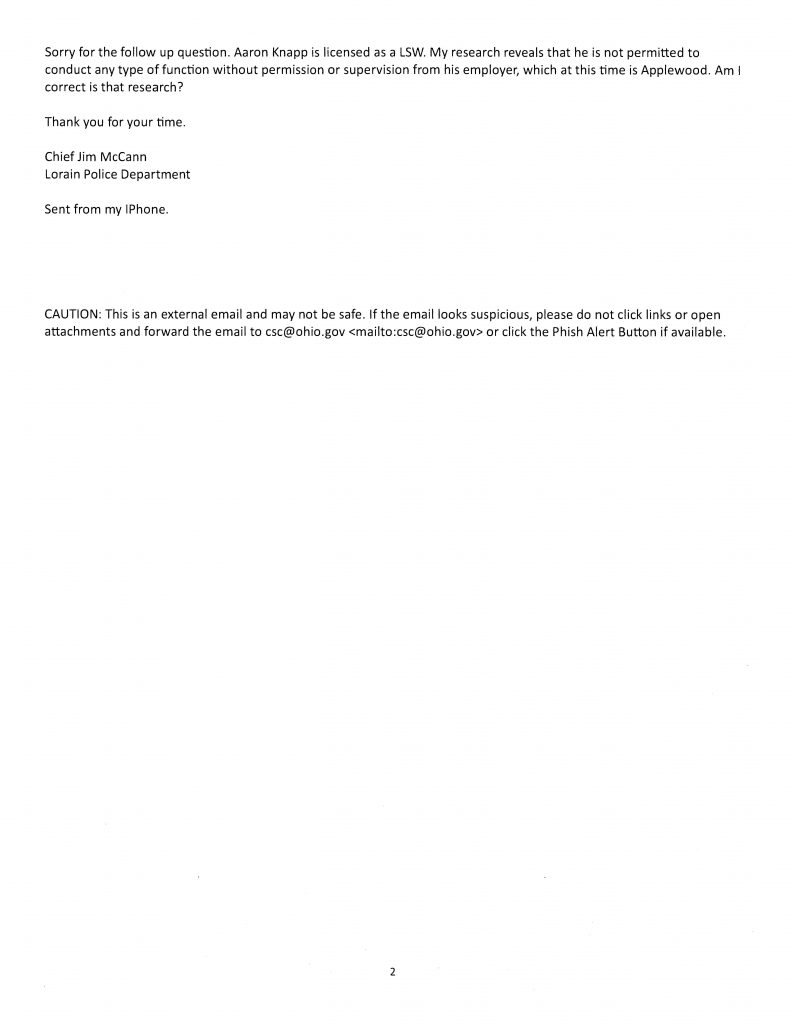

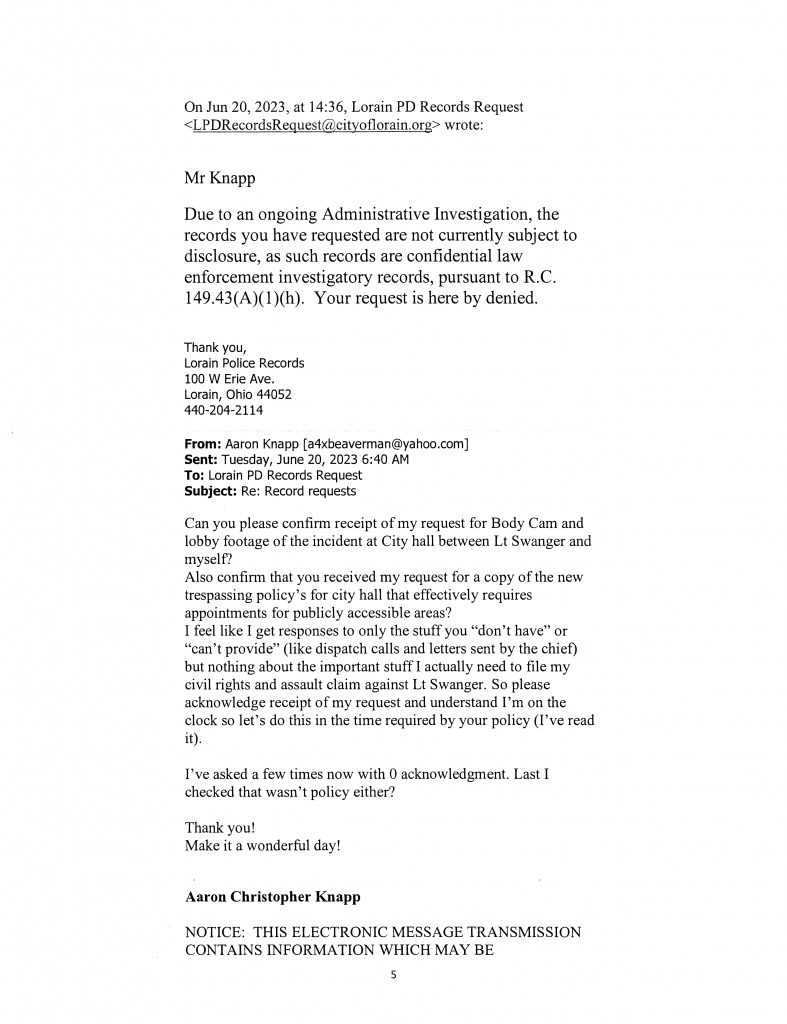

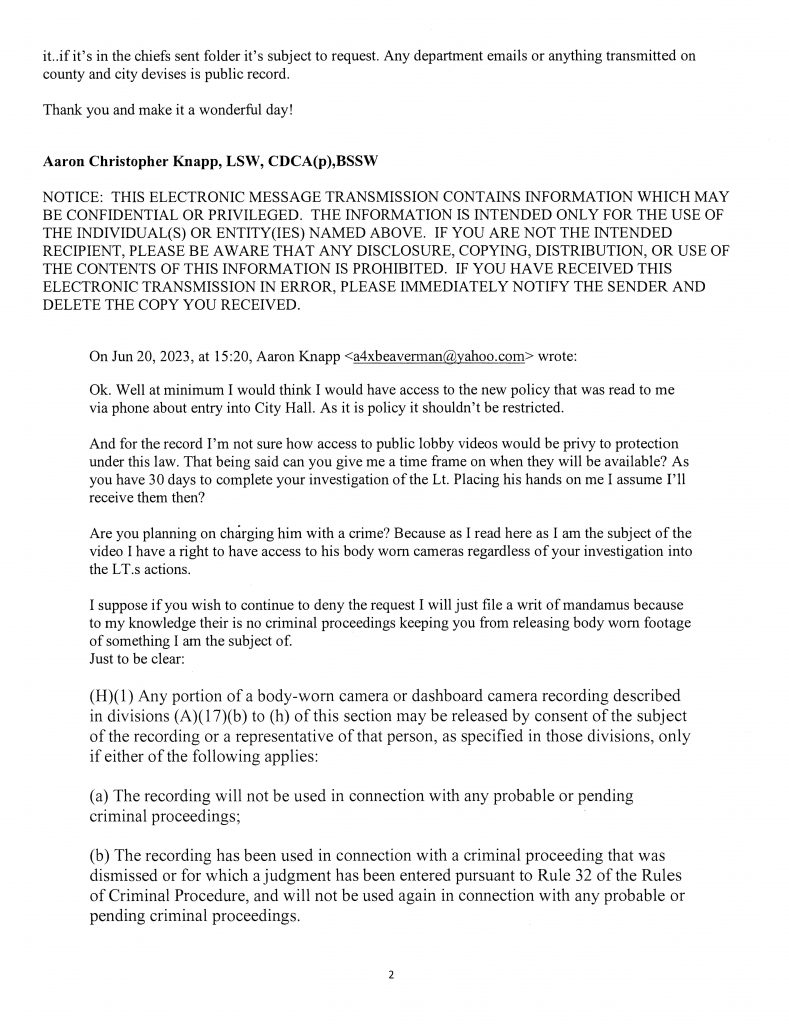

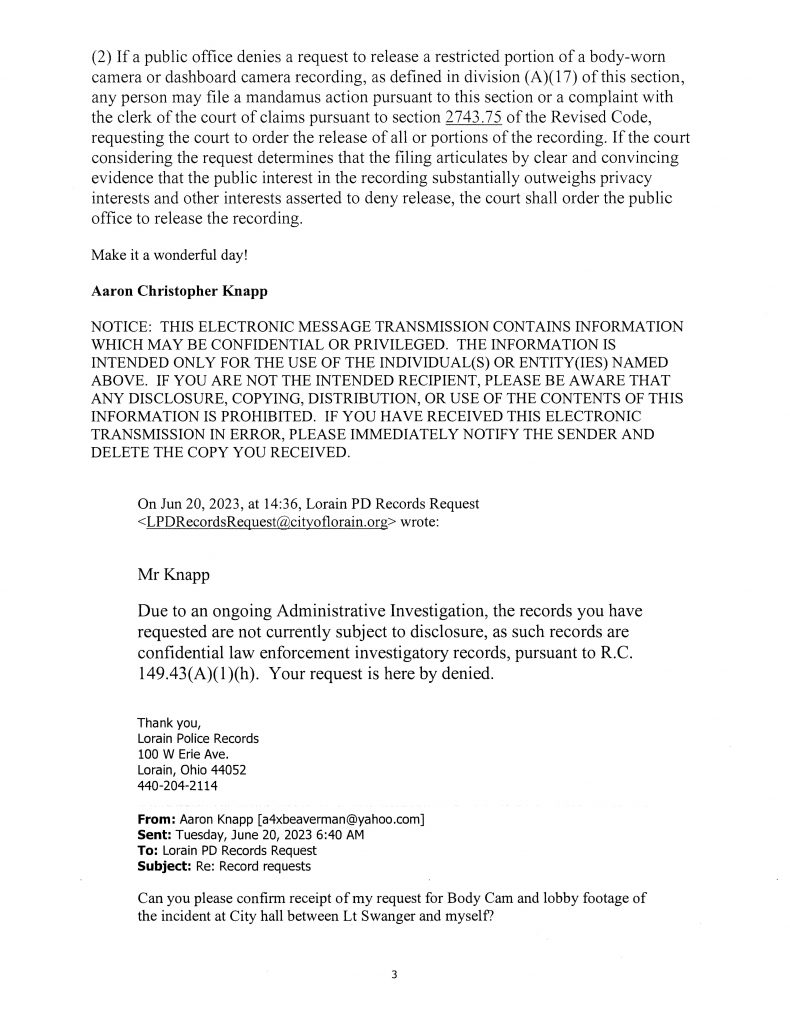

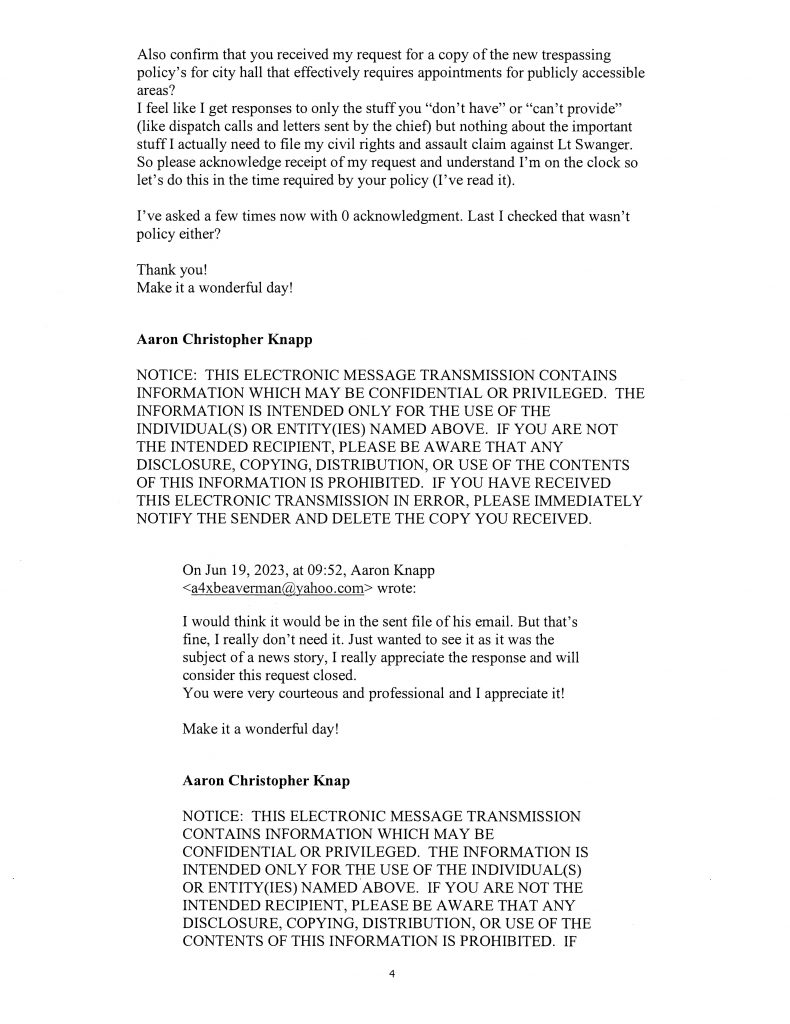

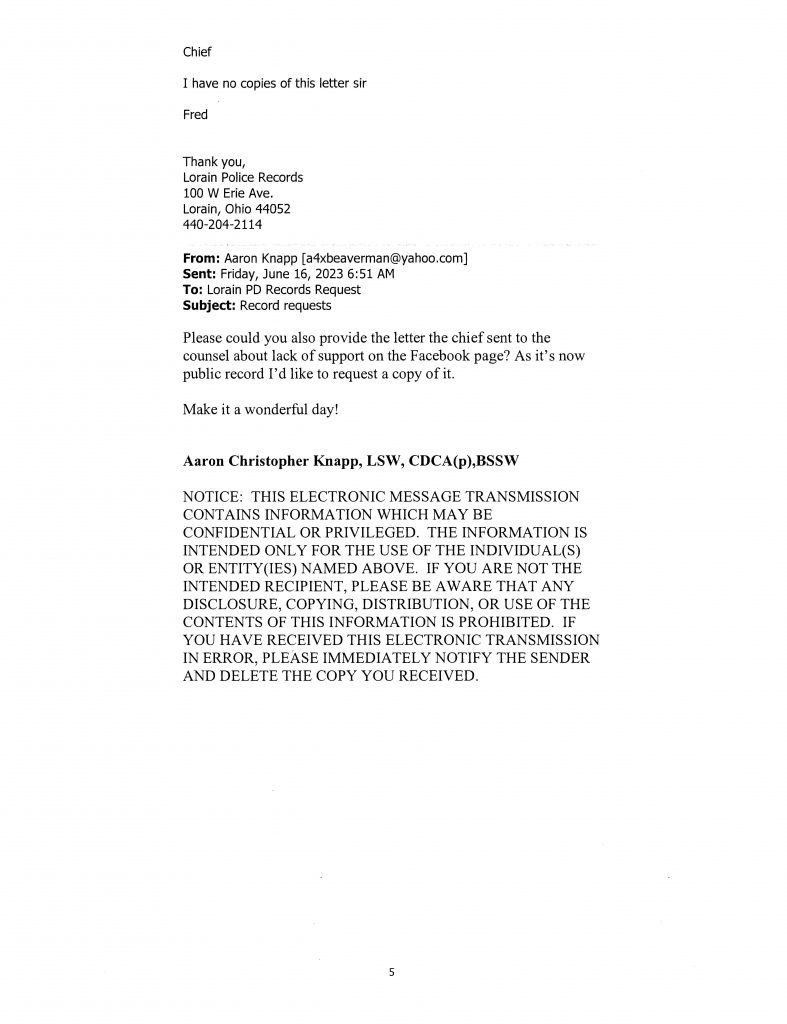

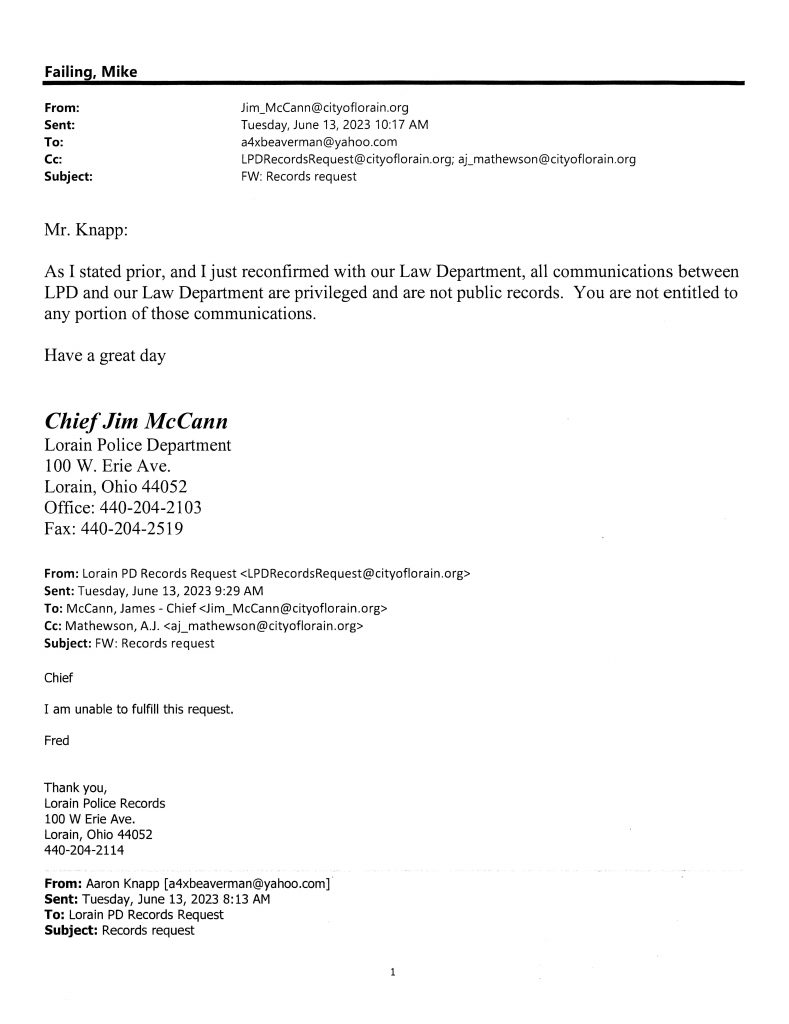

Public Records Requests Became a Trigger, Not a Right

When Asking for Records Became a Punishable Act

Ohio public records law is explicit and intentionally uncomplicated. A requester is not required to justify the request, explain motive, demonstrate relevance, or seek permission. The statute exists precisely to remove discretion from officials whose interests may be implicated by disclosure. Access to records is a right, not a favor, and it is designed to function even when the requester is inconvenient, persistent, or critical.

Yet each time I requested records touching law enforcement, the courts, or politically sensitive actors, the response followed a consistent and recognizable pattern that departed sharply from that statutory design.

Initial responses were delayed well beyond reasonable timeframes, often without written explanation. Records were declared nonexistent, only to later surface in partial or redacted form. Disclosures that were eventually produced directly contradicted earlier assertions that no responsive records existed. Claims of privilege were invoked broadly, without accompanying privilege logs or statutory citations sufficient to allow meaningful review. Decisions that should have been documented in writing were instead conveyed verbally, insulating them from challenge and leaving no record to appeal or examine.

This pattern did not occur once. It repeated across requests, across offices, and across subject matter. Each request that touched a sensitive issue followed the same arc. Delay. Denial. Informal explanation. Partial release. Silence.

As I persisted, the tone and posture of the responses shifted. I was no longer treated as a member of the public exercising a statutory right. I was treated as a disruption to be managed. Communications became guarded. Written responses narrowed. Responsibility for decisions was deflected between offices. Questions were answered indirectly or not at all. The process itself became the barrier.

Over time, the process itself became punitive. Each delay increased the cost of persistence. Each informal explanation eliminated a paper trail. Each partial disclosure forced additional requests. Each verbal decision foreclosed review. What unfolded was exhaustion by design.

Resistance does not require overt denial to be effective. It relies on friction, delay, ambiguity, and the quiet reassignment of responsibility.

See Hundreds of emails and denials here:

https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:VA6C2:bf86ce6a-f174-4759-9dcf-20c848426ac9

When Education, Licensure, and Regulation Demand Courage but Institutions Punish It

How the Gap Between What Is Taught, What Is Licensed, and What Is Tolerated Produces Harm by Design

The warning reflected in this record cannot be fully understood without examining the expectations imposed by social work education, professional licensure, and state regulation in Ohio, and then measuring those expectations against what institutions actually tolerate when those standards are honored in practice. The harm documented here does not arise from confusion about my role or misunderstanding of professional boundaries. It arises from a structural contradiction built directly into the profession’s training and oversight framework.

Social work education in Ohio is explicit and unambiguous about the role of conscience, advocacy, and ethical resistance. Programs such as those taught at The Ohio State University College of Social Work do not train social workers to function as passive service providers operating safely within fixed institutional hierarchies. They train them as ethical actors. Students are taught that harm is often systemic, that injustice is frequently embedded in policy and practice, and that professional responsibility does not end at individual service delivery. It extends to documentation, advocacy, and intervention when systems themselves become sources of abuse, discrimination, or civil rights violations.

This is not implied instruction. It is explicit. Students are taught that neutrality in the face of institutional harm is not professionalism. It is abandonment. They are taught that silence is not ethical restraint when power is misused. It is complicity. Macro practice, policy advocacy, and systems level accountability are presented not as optional career paths, but as legitimate and necessary expressions of professional identity.

That expectation does not end at graduation. It is reinforced and formalized through licensure by the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist Board. By granting a license, the State of Ohio affirms that a social worker is ethically bound to uphold standards that explicitly reject silence in the face of wrongdoing. Licensure is not merely a credential. It is a declaration that the individual has been trained, evaluated, and authorized to exercise ethical judgment, including judgment that may challenge institutional behavior.

The Board’s ethical framework emphasizes integrity, accountability, social justice, and the obligation to address systemic injustice. Continuing education requirements reinforce these principles year after year. The regulatory message is consistent. Ethical courage is not optional. It is expected.

Yet the lived reality documented here exposes a stark and damaging disconnect between what social workers are taught, what they are licensed to do, and what institutions actually permit without retaliation.

When a social worker applies training and licensure obligations within a narrowly tolerated service role, institutions are comfortable. Ethics are celebrated when they are symbolic. Advocacy is applauded when it is abstract. Accountability is welcomed when it does not threaten power, reputation, or control.

But when those same obligations are applied outward, toward law enforcement practices, court related conduct, public records compliance, or government accountability, the posture changes. Ethical action is no longer treated as professional integrity. It is treated as disruption. Documentation becomes “fixation.” Persistence becomes “harassment.” Lawful oversight becomes “threatening behavior.”

At that point, the system does not argue with the ethics themselves. It does not rebut the training. It does not challenge the licensure standards. Instead, it contains the practitioner.

Containment does not require formal discipline. It does not require revocation of license or written findings of misconduct. It operates through informal pressure points. Communications are redirected. Access narrows. Professional standing becomes precarious. Regulatory systems that exist to protect ethical practice are quietly invoked as instruments of risk rather than shields against retaliation.

This is the core contradiction. The same system that educates social workers to challenge injustice, licenses them to act with ethical independence, and publicly promotes accountability fails to tolerate those actions when they implicate powerful institutions. Ethics are demanded in theory and punished in practice.

This contradiction is not accidental. It is structural. It allows institutions to benefit from the moral legitimacy social workers provide while neutralizing that legitimacy when it becomes inconvenient. The profession is celebrated for its values, but constrained in its application. Courage is required, but only up to an invisible line that cannot be crossed without consequence.

The result is predictable harm. Social workers learn, often early in their careers, which parts of their training are safe to apply and which parts carry unacceptable professional risk. Advocacy is compartmentalized. Ethics are selectively enforced. Silence becomes a survival strategy rather than a moral failure.

From an oversight perspective, this gap is deeply dangerous. It creates a profession that appears ethically robust on paper while being operationally constrained in reality. It preserves the appearance of ethical governance while hollowing out its substance. No single action looks retaliatory in isolation. No single actor appears solely responsible. Each decision can be justified as discretionary. Each silence can be framed as restraint. Together, they produce professional harm by design.

This record exists to make that contradiction visible.

It exists to show that the issue is not whether one social worker exercised poor judgment, but whether a system can continue to demand ethical courage while punishing those who exercise it beyond institutionally comfortable boundaries. If licensure requires advocacy, but advocacy results in exclusion, then licensure becomes a liability rather than a safeguard.

That is not a personal grievance. It is a structural warning.

Licensure cannot be both a mandate for ethical courage and a vulnerability to be exploited when that courage becomes inconvenient.

When the Court Ordered Scrutiny and the Executive Quietly Closed the File

Judicial Referral, Conflicted Actors, and the Meaning of a “Do Not Present” Decision

At a critical point in this matter, the process moved beyond informal complaints, internal discretion, and administrative maneuvering and entered the judicial sphere. That transition matters. Once a court directs that an investigation occur, the question is no longer whether an agency prefers to act, or whether an executive office finds the inquiry convenient. The question becomes whether the rule of law itself is being respected.

Judicial referral is not advisory commentary. It is not a suggestion. It is an exercise of judicial authority intended to impose structure, independence, and accountability where other mechanisms have failed. Courts do not direct investigations so that they may be handled casually, resolved informally, or extinguished quietly. They do so because unresolved allegations implicate legal standards, constitutional duties, or public trust in a way that demands a documented, reviewable process.

Judge Ewers reviewed the matter and directed that it be investigated. That act carried with it an expectation that evidence would be gathered, witnesses evaluated, conclusions reached, and the outcome communicated on the record, including back to the court that ordered the inquiry. Whether the ultimate conclusion favored prosecution or declination was not the central issue. Process was. Independence was. Documentation was.

What followed did not meet that standard.

Rather than receiving a written investigative report, findings, or a formal declination notice transmitted to the court, I received a verbal communication. Prosecutor Tony Cillo contacted me by phone and stated that the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office had reached a “do not present” decision, commonly referred to as a DNP.

There was no accompanying documentation. There was no written explanation of the scope of the investigation. There was no indication of what evidence was reviewed, which witnesses were interviewed, or what legal standards were applied. There was no memorandum, no report, no declination letter, and no notice transmitted back to Judge Ewers. A judicially initiated inquiry was terminated verbally by an executive office without a paper trail.

This is not a minor procedural defect. It is a breakdown in the separation of powers.

A “do not present” decision is not a finding of fact. It is not an adjudication. It is not an exoneration. It is a discretionary prosecutorial decision not to present a case for charging. That discretion is legitimate only when exercised transparently, independently, and free of disqualifying conflicts. When it is conveyed orally, without documentation, by actors whose neutrality is already compromised, it loses the institutional legitimacy the term is meant to carry.

Equally important is what did not happen. The court was not notified in writing that its directive had been fulfilled. There was no return to the judge explaining the outcome. There was no opportunity for the court to assess whether its referral had been handled with independence or whether the inquiry had been prematurely foreclosed. The judicial branch was effectively cut out of its own referral.

This inversion matters. Courts do not exist to rubber stamp executive discretion after the fact. When a judge orders scrutiny, executive actors do not acquire authority to quietly override that scrutiny through informal closure. Doing so transforms judicial oversight into a symbolic gesture rather than a meaningful check on power.

The absence of documentation also foreclosed oversight by any external body. A verbal decision cannot be appealed. It cannot be evaluated. It cannot be independently reviewed. It leaves no record for the public, for oversight authorities, or for the judiciary itself to examine. Informality in this context does not reflect efficiency. It reflects insulation.

What makes this especially troubling is the context in which the decision was made. At the time the DNP was communicated, conflicts of interest were not hypothetical. They were already documented and unresolved. The same offices controlling the investigative outcome were entangled in related disputes, public records conflicts, and prior communications directly touching the subject matter. Yet no special prosecutor was appointed. No independent investigative agency was engaged. No recusal occurred.

The result was predictable. A process that should have been formal, independent, and documented was instead closed quietly, verbally, and without accountability.

I was not asking for a particular outcome. I was not demanding charges. I was asking for process. I was asking for independence. I was asking for a record that could be examined, challenged, or defended on its merits. What I received instead was a conclusion without findings, a decision without explanation, and a closure that could not be scrutinized.

From an oversight perspective, this moment is pivotal. It demonstrates how judicial authority can be neutralized not through open defiance, but through procedural erosion. When executive actors respond to court ordered scrutiny with undocumented discretion, the rule of law is weakened without ever being openly challenged.

This was not the end of the pattern. It was its confirmation.

The same approach that characterized earlier stages of this matter reappeared here. Avoid written findings. Avoid formal responses. Route decisions through informal channels. Preserve deniability. Exhaust the individual raising concerns rather than address the concerns themselves.

That is not justice. It is how accountability is quietly dismantled.

A judicially directed investigation was closed through an executive phone call, not through a written notice to the referring judge.

Conflict of Interest Was Not Addressed, It Was Ignored

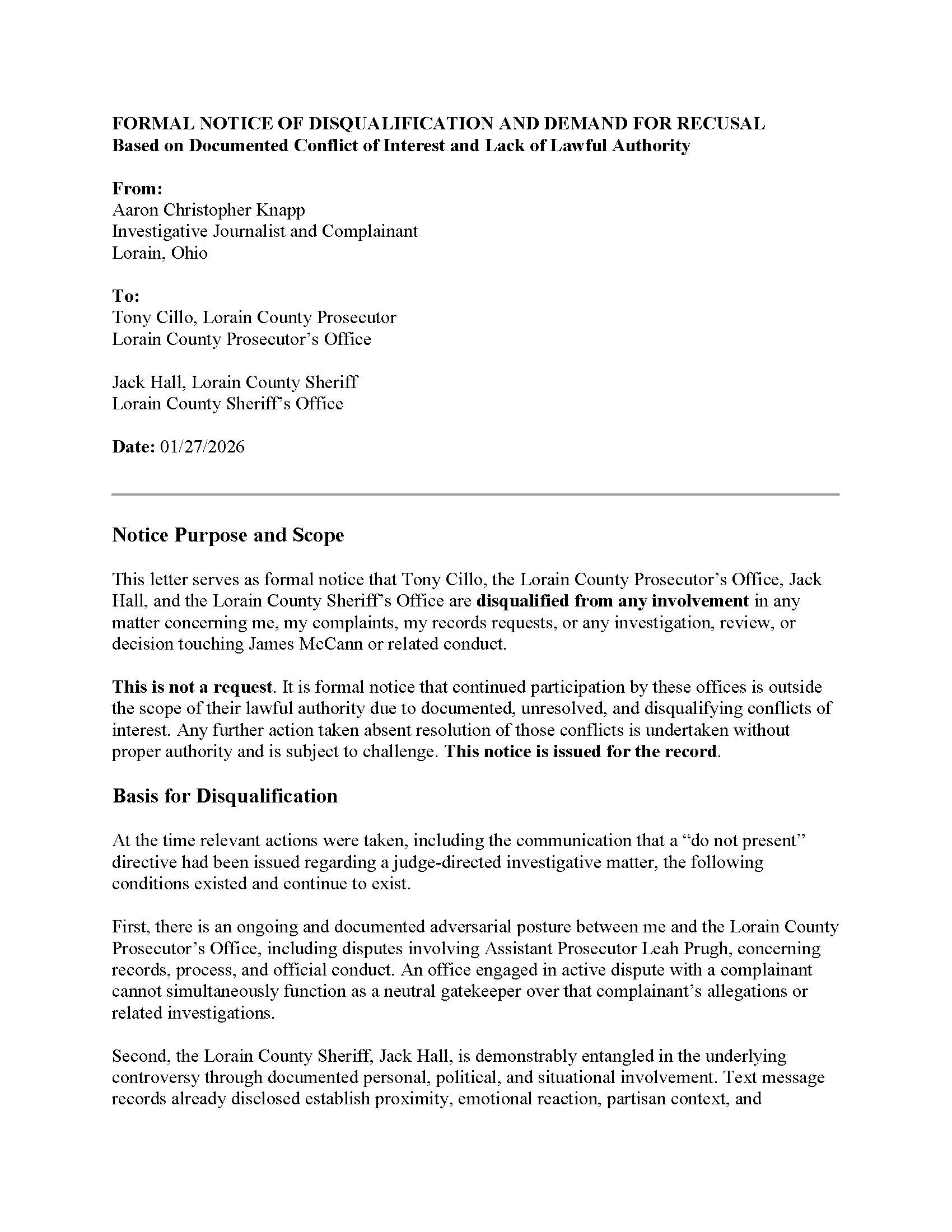

Why Recusal Was Required and Never Meaningfully Considered

At the time the “do not present” decision was communicated, the existence of conflict was neither hypothetical nor speculative. It was already active, documented, and unavoidable. I was engaged in an ongoing and adversarial dispute with the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office concerning public records compliance, statutory interpretation, and official conduct. That dispute was concrete. It involved specific records requests, specific denials, specific legal positions taken by the office, and ongoing challenges to those positions. The Prosecutor’s Office was not a neutral observer. It was a party with its own exposure and interests at stake.

An office that is actively defending its own conduct against a complainant cannot simultaneously serve as a neutral gatekeeper over matters involving that same individual. That principle is not controversial. It is foundational to due process, administrative fairness, and public trust. Neutrality is not preserved by assertions of professionalism or good faith. Neutrality is preserved by structural separation when conflicts arise.

The Lorain County Sheriff’s Office was likewise not operating in a posture of detachment. The Sheriff was not a distant actor evaluating allegations from outside the controversy. Existing political, professional, and institutional entanglements placed the office squarely within the same ecosystem of influence and exposure. In oversight contexts, this distinction matters. Actual bias does not need to be proven for recusal to be required. The appearance of compromised neutrality alone is sufficient, because public confidence depends on the integrity of the process, not merely the intentions of those administering it.

In response to these conditions, I issued a formal notice of disqualification and demand for recusal. This was not a rhetorical objection, a public complaint, or an attempt to delay proceedings. It was a written notice, placed on the record, that identified the specific conflicts, explained why continued involvement was improper, and demanded removal from decision making roles to preserve procedural integrity. The purpose of the notice was corrective, not obstructive. It sought to ensure that any investigation, review, or prosecutorial determination would be handled by actors whose neutrality could not reasonably be questioned.

What followed was not a denial. It was not an explanation. It was not a referral. There was no written response addressing the substance of the conflict. There was no acknowledgment that the conflict had been evaluated. There was no referral to an independent authority. There was no response in the record at all.

Instead, there was silence.

That silence is not neutral. Silence in this context functions as avoidance. By declining to respond, conflicted actors retained control over the process while avoiding any obligation to justify their authority to do so. The absence of a response foreclosed meaningful challenge, appeal, or review. It allowed decision making to proceed as though the conflict did not exist, despite the fact that it had been explicitly identified and documented.

This matters because every action taken after that point rests on a compromised foundation. Decisions made without addressing known conflicts cannot be insulated by procedural labels or discretionary authority. When recusal is properly demanded and ignored, the integrity of subsequent actions is not merely weakened. It is structurally undermined. The issue ceases to be whether individual decisions were correct and becomes whether the process itself was capable of producing legitimate outcomes at all.

The failure to meaningfully address conflict also reveals a broader institutional pattern. When conflicts are inconvenient, they are not resolved. They are bypassed. When recusal would introduce independent oversight, silence becomes the preferred response. That pattern does not correct error. It preserves authority at the expense of credibility.

This section of the record is therefore not about personal grievance. It is about process integrity. Oversight cannot function where conflicts are identified, documented, and then ignored. A system that refuses to confront its own conflicts does not merely risk error.

It guarantees mistrust.

Silence in this context is not neutral. Silence preserves outcomes while avoiding scrutiny.

Professional Consequences Extended Beyond Government

How Ethical Advocacy Was Quietly Converted Into Professional Exclusion

As these events unfolded, the consequences did not remain confined to government offices, public agencies, or formal decision makers. They moved outward, away from the visible structures of authority and into the informal but powerful terrain of professional life. What began as institutional resistance inside government gradually transformed into something more diffuse, more deniable, and more difficult to confront: quiet professional exclusion. This shift matters because it is here, outside the reach of formal process and written decision making, that retaliation becomes most effective while remaining hardest to prove.

My professional world began to contract in ways that were unmistakable to anyone living inside it, yet nearly impossible to point to as a single act. Opportunities that had previously existed without controversy disappeared without explanation. Invitations that once arrived routinely simply stopped. Conversations that had been collegial and open became cautious, abbreviated, or ceased altogether. Relationships cooled not because of any identified misconduct, not because of any formal finding, and not because of any articulated concern, but because proximity itself appeared to carry risk. Association became something to be managed rather than assumed.

No one issued a formal ban. No one sent a termination letter citing cause. No institution documented a decision that could be appealed, challenged, or reviewed. Instead, access narrowed incrementally and almost invisibly. Cooperation became conditional. Participation required silence, distance, or disengagement from the issues that had already been labeled disruptive. The message was never stated outright, but it did not need to be. The conditions spoke for themselves.

This is how professional exclusion operates when it is sophisticated. It does not rely on overt punishment. It relies on withdrawal. It relies on the fact that professional ecosystems function through trust, reputation, referrals, and informal validation. When influential institutions or actors signal, even indirectly, that someone is “difficult,” “unsafe,” or “not worth the trouble,” others adjust their behavior accordingly. They do not need to be instructed. Risk avoidance does the work. Silence spreads faster than explanation.

What makes this form of retaliation particularly corrosive is that it leaves no clear trail. Each individual decision can be rationalized in isolation. A meeting not scheduled can be explained as a calendar conflict. An email not returned can be attributed to workload. A contract not renewed can be framed as a budgetary choice. An opportunity redirected elsewhere can be dismissed as coincidence. Viewed one at a time, none of these acts appears actionable. Taken together, they reshape a career.

For licensed professionals, this mechanism is especially damaging. Social work, journalism, and court adjacent roles depend on access, collaboration, and institutional goodwill. They depend on being allowed into rooms, onto cases, and into conversations that are rarely guaranteed by right. When those doors begin to close quietly, the effect is not merely economic. It is existential. The professional is not told they have done something wrong. They are simply made less present, less visible, and less viable.

This quiet exclusion also serves a secondary function. It sends a message to others without ever having to articulate one. Colleagues observe what happens to the person who persists, who documents, who refuses to let issues drop. They notice the shrinking circle, the absence of opportunities, the subtle reputational shift. No memo is required. The lesson is learned through observation. Silence becomes the safer path. Distance becomes self protection.

From the outside, nothing appears amiss. There is no record to subpoena. No finding to contest. No decision maker to confront. From the inside, the meaning is unmistakable. Ethical advocacy has been converted into professional liability. Not through formal discipline, but through attrition. Not through accusation, but through abandonment.

This is why retaliation cannot be evaluated solely by looking for explicit adverse actions. Modern institutional retaliation rarely looks like punishment. It looks like being slowly edged out of spaces you were trained, licensed, and ethically obligated to occupy. It looks like the steady disappearance of professional oxygen. It looks like a career narrowed not by failure, but by refusal to be silent.

The harm here is not merely personal. It is structural. When professionals observe that speaking up leads not to correction or even principled disagreement, but to quiet exclusion, they internalize a lesson no ethics course intends to teach. Ethics are aspirational, but only within limits. Accountability is encouraged, but only when it does not disturb power. Persistence is tolerated, but only until it becomes effective.

This is how systems protect themselves without ever appearing to retaliate. They comply with the appearance of legality while hollowing out its substance. Rights remain intact on paper. Protections remain nominally available. But the cost of exercising them becomes so high, and so isolating, that only the most willing to absorb sustained damage continue.

What occurred here demonstrates how ethical advocacy can be neutralized without ever being formally punished. It shows how professional exclusion can be imposed without documentation, without due process, and without accountability. And it reveals why so many professionals eventually choose silence, not because harm has ceased, but because the system has made the cost of naming it unbearable.

Modern institutional retaliation rarely looks like punishment. It looks like abandonment.

The Question the System Has Refused to Answer

Why Follow the Rules at All

Ohio publicly promotes a culture of reporting wrongdoing. Government agencies repeatedly invoke the language of transparency, accountability, and civic engagement, not as abstract ideals, but as expectations of responsible citizenship. Training materials, public statements, and official policies encourage people to speak up, to question irregularities, and to participate in oversight when government action affects the public. These messages are not subtle. They are framed as civic duties.

Social work education reinforces this mandate with even greater force. Advocacy is not optional. Ethical resistance to harm is not discretionary. Licensure standards and professional codes explicitly require social workers to act when they observe misconduct, abuse of authority, or systemic practices that place individuals or communities at risk. Silence in those circumstances is treated not as neutrality, but as failure. The profession does not merely permit advocacy. It demands it, even when doing so creates discomfort or opposition.

Public records law is designed to support the same framework. Ohio Revised Code 149.43 exists for a reason. It is structured to allow ordinary citizens, journalists, and professionals to obtain government records without having to prove motive, justify curiosity, or demonstrate institutional standing. The law presumes that oversight is a public good, and that access to records is a safeguard against misuse of power. It is meant to function precisely when officials would prefer not to be scrutinized.

The Constitution completes this alignment. Speech, petition, and the right to challenge government action are not fringe protections. They are foundational. The legal framework does not merely tolerate criticism of government. It anticipates it, protects it, and treats it as essential to democratic function. Retaliation for lawful speech and petition is not supposed to be a risk that citizens are expected to calculate.

On paper, these systems reinforce one another. Civic culture, professional ethics, statutory law, and constitutional protections all point in the same direction. See harm. Document it. Speak up. Use lawful tools. Persist.

In practice, my experience demonstrates a profoundly different lesson.

If you see something and say something, you become the problem.

If you document misconduct, you are labeled disruptive.

If you insist on records, you are treated as hostile.

If you persist lawfully, you are isolated.

If you refuse to disappear, the system waits you out.

What emerges is not an accidental contradiction. It is a structural one. The rules are celebrated publicly, but enforced selectively. Advocacy is praised in the abstract, but punished in application. Oversight is welcomed until it becomes effective. At that point, the system shifts from engagement to containment.

This is the question the system has refused to answer. If the ethical, legal, and constitutional frameworks are real, then why is adherence to them treated as a threat. Why does following the rules produce professional risk rather than institutional correction. Why does lawful persistence trigger exclusion instead of response.

The answer matters because systems teach through consequence. Professionals learn not from mission statements, but from outcomes. When ethical action results in isolation, surveillance, or career harm, the lesson transmitted to others is clear. The rules exist in theory. Compliance is conditional.

That is how oversight erodes without being formally dismantled. No law needs to be repealed. No policy needs to be rescinded. The system simply demonstrates, through repeated example, that those who rely on ethical training and legal rights will be left unsupported when pressure is applied.

This is not a personal dilemma. It is a systemic one. When institutions punish the use of the very mechanisms they claim to value, the question is no longer why someone spoke up. The question becomes why anyone would.

If the practical answer to “see something, say something” is isolation, then the slogan is dishonest.

What This Is and What It Is Not

A Record Seeking Oversight, Not Sympathy

This record is not a vendetta. It is not a campaign against individuals, personalities, or reputations. It is not an effort to assign moral blame, settle personal grievances, or demand emotional validation. It does not ask anyone to choose sides, to accept one narrative over another, or to substitute sympathy for analysis. It is not an appeal for special treatment, personal vindication, or institutional apology.

It is also not an attempt to reframe disagreement as persecution. Disputes happen. Professional tension exists. Tone can be misread. Intent can be debated. None of that is what is at issue here. This record does not hinge on subjective impressions, personality clashes, or how any individual “felt” about another’s conduct. It does not rest on speculation or inference. It rests on documents, timelines, communications, and the observable consequences that followed.

What this record seeks is independent, external oversight.

It is a request for review by someone with lawful authority, institutional distance, and no personal, professional, or political stake in the outcome. It asks for examination of the entire sequence as a system, not as disconnected moments or isolated decisions. The question is not whether any single action can be rationalized in isolation, but whether the pattern that emerges across agencies, roles, and time is consistent with lawful, ethical, and transparent governance.

This record asks for scrutiny not only of what decisions were made, but how they were made. It asks how concerns were handled once they became inconvenient. It asks how communication shifted as scrutiny increased. It asks why informal, verbal, and undocumented processes repeatedly replaced written, reviewable ones at the precise moments when accountability would have been triggered. It asks why outcomes were implemented first and justified later, if at all.

Most importantly, it asks whether professional and constitutional protections functioned as intended when pressure was applied, or whether they collapsed into discretionary enforcement once the subject of scrutiny refused to disengage.

This is not a request for belief. It is a request for examination. It does not ask anyone to accept conclusions in advance. It asks that the full record be reviewed without minimization, fragmentation, or personalization. It asks that oversight be exercised in the way oversight is meant to function: dispassionately, independently, and on the merits.

If the actions documented here withstand that review, they should be affirmed openly and without reservation. If they do not, the remedy is not silence or erasure, but correction. Either outcome requires the same first step. Someone with authority must actually look.

Informality protects outcomes while avoiding accountability.

Closing Statement for the Record

A Final Thought on Ethics, Power, Credibility, and What This Record Is Meant to Preserve

I did what I was trained to do. I did what the law permits and, in many respects, requires. I did what my profession explicitly teaches is not optional when harm, abuse of authority, or systemic failure becomes visible. I documented. I asked questions. I relied on records rather than rumor. I raised concerns through lawful channels. I persisted when silence replaced answers.

None of those actions were impulsive. None were hidden. None were taken lightly or without awareness of the personal and professional risk involved. They were taken deliberately, with full understanding that ethical principles only matter when they are applied under pressure. Ethics that function only when they are convenient, cost free, or institutionally comfortable are not ethics at all. They are slogans.

What followed was not correction. It was containment.

James McCann, as Chief of Police for the City of Lorain, failed to correct documented constitutional and juvenile records concerns when they were brought to him directly. Instead, the record shows a shift away from addressing exposure of protected juvenile information and toward questioning the credibility, motives, and mental state of the person who documented it. That choice set the tone for everything that followed.

After McCann, the continuation of false or misleading narratives did not stop. Assistant Law Director Joseph LaVeck (under the and Captain Jacob Morris, acting within law enforcement authority, perpetuated versions of events that conflicted with documented records, failed to correct known inaccuracies, and did not take steps to refer or report conduct that raised clear questions of legality. Their involvement reflects continuity, not correction.

Rey Carrion enters this record not as a neutral observer, but as an actor whose conduct intersected with the same unresolved issues and whose role was never meaningfully examined despite the gravity of the underlying concerns.

Within Internal Affairs, Kyle Gelenius failed to perform the most basic function of the office. There was no meaningful investigation, no documented findings, no referral for independent review, and no closure that met professional or statutory standards. An Internal Affairs process that produces no accountability, no transparency, and no record is not an oversight mechanism. It is an administrative dead end.

The failure did not stop at city police.

Every law enforcement officer who encountered this matter before and after the initial exposure, and who declined to treat it as a potential crime or refer it accordingly, bears responsibility for that omission. That includes the Sheriff of Lorain County, past and present, who possessed authority to investigate independent of city control and did not meaningfully exercise it.

It includes the Lorain County Prosecutor, past and present, whose office remained involved despite documented conflicts and who failed to issue a transparent charging decision, declination, or written explanation that could be reviewed or challenged.

It includes the Chief of Police for the City of Lorain, past and present, who inherited not only authority but obligation, and who did not correct the record, initiate accountability, or acknowledge the institutional failure that preceded them.

None of these actors lacked authority. None lacked access. None lacked notice.

Each took an oath of office. That oath did not require them to protect colleagues, preserve institutional comfort, or wait out scrutiny. It required them to uphold the law, to act when violations became known, and to ensure that crimes are investigated rather than managed out of existence.

This record exists to show how violations can persist without formal discipline, how investigations can be functionally closed without findings, how conflicts can be acknowledged informally while ignored procedurally, and how silence can be used as a governance strategy rather than a temporary lapse.

It exists so that no one can later claim ignorance. The emails exist. The documents exist. The timelines exist. The removals occurred. The non actions are documented.

I did not choose this conflict. I did not escalate it. I did not personalize it. I responded to it as I was trained to respond to harm and abuse of authority. With documentation. With persistence. With reliance on law rather than discretion, and process rather than influence.

If adherence to ethics, licensure obligations, and constitutional process is met with retaliation, professional exclusion, and quiet erasure, then the failure is not individual. It is institutional.

This record is not written for sympathy. It is written for history. It is written so that when institutional memory fades, the evidence does not.

If that response is now deemed unacceptable, then the failure does not belong to me. It belongs to a system that has forgotten why ethics exist, what oversight is for, and how quickly credibility collapses when conscience is punished instead of protected.

Copyright

© Aaron Knapp / Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced, republished, or redistributed without written permission, except for brief quotations used for commentary, criticism, or news reporting with attribution.

Legal Disclaimer

This publication is for informational and journalistic purposes only. It reflects reporting, documentation, and analysis based on records, correspondence, and observed events as described. It is not intended to accuse any individual of a crime, nor to assert facts beyond what is supported by the referenced record. Where allegations, interpretations, or opinions are expressed, they are presented as such. Readers are encouraged to review underlying documents and draw their own conclusions.

Not Legal Advice

Nothing in this publication constitutes legal advice. This article is not a substitute for consultation with a licensed attorney regarding any specific legal matter. If you need legal advice, consult counsel.

AI Photo and Graphics Disclosure

Some images or graphics used in connection with this publication may be generated or enhanced using artificial intelligence tools for illustrative or editorial purposes. AI generated visuals are not presented as factual depictions of real events unless explicitly stated. Document screenshots and public records images, where used, are presented as documentary evidence and are not AI generated.

Editorial Note on Juvenile Records

This article does not republish juvenile records. Where juvenile related materials are referenced, the discussion is limited to governance, process, and accountability concerns. Any document images inserted should avoid identifying information and should not display protected juvenile content.

The ethics portrayed at every level of the Nancy Smith prosecution at every stage Of the debacle expose too a system of broken and failure of ethical and professional standards. It made no difference whether it was your professional career or actual loss of Liberty and Freedom! You’re just another example of how the cabal operates then and now. Justice is elusive where its actors are amoral. Hide exculpatory evidence, refuse to investigate it, falsely testify, defraud the defendant, the citizens, the Court, lie under oath, suppress the truth, practice with satanic goals, and strive only for your perception of your own political goals and you get Lorain’s circumstances as existing today. Leadership deficiencies are rooted in amoral behaviors. Practicing only lip service to Jehovah God. Abuse of Authority and Deriliction of Duty are crimes committed by those who despite the privilege granted to them as public servants refuse to honor their Oaths of Office and THE WORD OF GOD! That my friends and enemies is the problem identified by Mr. Knapp though he expresses it in a a secular manner. If you do bad, you go to hell.

REPENT and BE SAVED.

Do good works and praise God.