The Disqualification Attempt That Breaks the Law

How Sheffield Lake’s leadership is trying to overturn a certified election, silence seventy two percent of voters, and rewrite Ohio law to block Aden Fogel from taking office.

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, LSW

Investigative Journalist and Government Accountability Reporter

Editor in Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker, LSW

Public Records Litigant and Research Analyst

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

I. Introduction: A Certification the City Suddenly Pretends Does Not Count

When the Lorain County Board of Elections certified the results of the 2025 Sheffield Lake municipal election, that was supposed to be the end of the story. Certification is not a suggestion. It is the formal legal acknowledgment that a democratic contest has been conducted according to law, that the ballots were properly counted, and that the voters will is final.

Aden Fogel did not squeak into office. He received roughly seventy two percent of the vote. That is not a fluke. It is not a razor margin. It is not the product of confusion. It is a landslide. In a functioning democracy, a landslide matters. Under Ohio law, a landslide backed by a certified result should be the last word.

Fogel’s past was not a secret. His convictions are decades old. They did not stop him from filing to run. They did not stop the Lorain County Board of Elections from accepting his petitions. They did not stop the Board from certifying him to the ballot. They did not stop the election from taking place. They did not stop the Board from certifying the results. They did not trigger any pre election protest. They did not cause the Secretary of State to issue any advisory warning the Board that he was ineligible.

Ohio’s statutory scheme is also not a mystery. Felony convictions in general do not automatically bar someone from running for or holding municipal office. Only specific types of public corruption crimes, like bribery and theft in office under R C 2921.02 and 2921.43, create a permanent disqualification from public office. Fogel’s record does not fit within that narrow category.

Lorain County itself is proof that Ohio does not impose a blanket ban on felons in local office. The county has literally had a council member with a felony recently seated with no legal challenge, no secretary of state intervention, and no attempt to invalidate the voters choice.

Yet, after all of this, after the election, after the certification, after seventy two percent of voters said yes, Sheffield Lake is now trying to reinvent the law in real time. The city’s law director and certain political voices are claiming that the Secretary of State somehow will not certify a felon, that this supposed refusal empowers the city to block Fogel from taking his seat, and that this is simply the way Ohio law works.

It is not.

What is happening in Sheffield Lake is not a neutral interpretation of the Revised Code. It is a political effort to undo an election result that a particular set of insiders did not like. It is an attempt to override the voters. And it does not stand alone. It sits on top of a long history of rule bending and selective enforcement inside Sheffield Lake government.

II. What Ohio Law Actually Says About Felony Convictions and Who Decides Eligibility

Ohio’s Constitution and the Ohio Revised Code are built around a simple principle. Elections belong to the voters. Courts and government actors are supposed to interfere with certified results only when there is a clear, specific legal command to do so.

Under R C 2961.01, a felony conviction may temporarily affect a person’s right to vote until those rights are restored. But only certain specific felonies involving corruption in public office create a permanent disability to hold public office. These are crimes like bribery, theft in office, and misuse of public authority. There is no statewide law that says any person with any felony is forever barred from running for or holding a city council seat. If the legislature intended to impose such a sweeping ban, it could have written that into the statute. It did not.

Furthermore, the question of who decides whether a candidate is eligible for the ballot is not left to improvisation. R C 3501.11 and R C 3501.21 place the responsibility for candidate qualification, petition review, and ballot eligibility squarely and exclusively on the county Board of Elections before the election. Under Ohio law, the Board of Elections is the gatekeeper of ballot access.

That means that when a candidate files petitions, the Board is required to conduct all of the statutory checks. The Board must verify signatures, confirm the petitions are timely and in the correct form, confirm that the candidate meets basic legal eligibility, and then either certify or reject the candidate. Once the Board certifies a candidate to the ballot, that determination is presumptively final unless someone acts during the narrow window of time that the law provides for challenges.

Those challenges have defined mechanisms. A formal protest can be filed under R C 3513.05 before the election. A writ of mandamus action can be filed in the Supreme Court of Ohio before the election to compel the Board to remove an ineligible candidate from the ballot. In both cases, the law is explicit. If there is a problem, it must be raised before the first ballot is cast, not after the last one has been counted.

None of that happened in this case. There was no pre election protest filed against Fogel’s candidacy. There was no mandamus action asking the Supreme Court to remove him. There was no attempt by the city’s law director to challenge his placement on the ballot during the time the law clearly allows. The statutory deadlines came and went in complete silence.

Once those deadlines pass and the election proceeds, Ohio courts treat the voters decision with extreme deference. Post election disqualification efforts are strongly disfavored because they overturn the expressed will of the people and destabilize the entire electoral process. The Supreme Court of Ohio has repeated this theme across multiple cases.

The city had every tool it needed to raise eligibility concerns before the election. It chose not to use any of them. The Board of Elections certified Fogel to the ballot. The Board ran the election. The Board certified the results. Under Ohio’s legal framework, that should be the end of any argument about whether he can be seated.

Sheffield Lake is now trying to resurrect an eligibility argument that expired months ago. They are not doing this because the law suddenly changed. They are doing it because the voters refused to produce the outcome that certain officials wanted. Under the doctrine of finality, and under basic principles of fairness, that is not how Ohio elections are supposed to work.

III. The Secretary of State Narrative: A Claim Without Legal or Statutory Basis

Central to the city’s public position is a claim that has been repeated in conversations, emails, and social media comments. The claim goes something like this. The Secretary of State will not certify a felon. Because the Secretary supposedly will not certify a felon, the city now has grounds to treat the election result as invalid and refuse to seat Fogel.

This claim sounds authoritative when stated in a Facebook comment or whispered in a council hallway. It collapses the moment it is held up against actual law.

Under R C 3501.11, the county Board of Elections is responsible for reviewing petitions, determining whether a candidate is qualified to appear on the ballot, and certifying candidates and results. That statute lays out the Board’s duties in detail. The Board checks signatures. The Board reviews forms. The Board verifies residency and other requirements. The Board places names on the ballot. The Board certifies the vote totals when the election is over.

Under R C 3501.04, the Secretary of State is designated as the chief election officer of the state. That role includes issuing directives, preparing statewide forms, prescribing uniform rules, supervising Boards of Elections, and generally ensuring that Ohio’s election machinery runs according to law. What it does not include is the power to conduct a second, post election eligibility review of municipal winners and reject individual candidates after a local Board of Elections has already certified the result.

There is no statute that authorizes the Secretary of State to dig into a municipal council member elect’s criminal history after an election and unilaterally declare the person unqualified. There is no directive that describes such a process. The Ohio Election Official Manual does not describe any second certification step in which the Secretary re evaluates municipal officeholders. The Secretary certifies statewide results and oversees statewide administration. Municipal winners certified by county Boards are not subject to a secret second round of vetting.

Ohio courts have reinforced this structure. In State ex rel. Polo v. Cuyahoga County Board of Elections, the Supreme Court of Ohio made clear that eligibility challenges must be brought during the statutory protest period and that attempts to raise them later are barred. In State ex rel. Brown v. Summit County Board of Elections and in other decisions, the Court has underscored that the Board of Elections is the proper forum for pre election qualification disputes, and that once the Board acts and the election is held, courts are reluctant to disturb that outcome.

There is no line of cases anywhere in Ohio law that establishes a special power for the Secretary of State to swoop in after a municipal election and retroactively disqualify a winner for a non disqualifying felony. That theory has no statutory hook, no rule based support, and no precedent.

What it does have is political utility.

When a story circulates that the Secretary of State will not certify a felon, it creates the impression that what is happening is inevitable and legally mandated. It suggests that the city has no choice. It is a way of laundering a political preference through a misrepresentation of law.

When a narrative is not grounded in any statute, directive, or case law but is repeated anyway as if it were binding, the question is not what the law allows. The question is who benefits from people believing that it does. In this case, the answer is obvious. The people who benefit are those who lost at the ballot box and want a second chance to get rid of a candidate whom seventy two percent of the voters supported.

The law director who leans on this Secretary of State narrative is not faithfully interpreting the Revised Code. They are inventing a process that does not exist in order to justify an outcome that the law does not authorize.

IV. The Voters Spoke, and Now Their Will Is Being Undone

Aden Fogel won seventy two percent of the vote. That number should not be treated as background noise. It is central to understanding why what Sheffield Lake is doing is so dangerous.

In a representative democracy, the people speak through elections. Under Ohio law, once an election has been conducted according to statute and the results certified, the voters decision is entitled to the highest level of respect and protection. This is not a slogan. It is a doctrine that the Supreme Court of Ohio has enforced consistently for decades.

In State ex rel. Quoist v. Board of Elections of Cuyahoga County, the Court stressed that elections belong to the people and that post election attacks on eligibility are inherently suspect because they invalidate votes cast in reliance on the rules in place at the time. In State ex rel. Polo, the Court held that parties who fail to use the tools available before an election cannot wait to see the outcome and then seek to disqualify the winner. In State ex rel. Brown, the Court emphasized that once results are certified, they are presumptively valid and should only be overturned in the rarest circumstances and under clear statutory authority.

Other cases, like State ex rel. Hansen v. Reed and State ex rel. Pennington v. Biviano, underline the same theme. Hansen warns that permitting post election procedural challenges would invite chaos and destabilize elections by encouraging losing parties to scour the process for technicalities after the fact. Pennington holds that even when there are technical defects that could have been discovered before the election, they cannot be used afterward to unseat a candidate when the challenger sat on their rights.

All of this reflects a single overarching concept. It is known as the doctrine of finality. Once the public has voted under the legal framework in place, the result is final unless the law clearly commands otherwise. Elections are not practice rounds. They are the point.

What Sheffield Lake is attempting to do violates this doctrine at its core. The city is treating the voters choice as provisional, as if their decision were an initial recommendation subject to a second round of review by insiders who did not like the outcome. Instead of respecting the certified result, the city is trying to change the eligibility standard after the ballots have already been cast.

If this maneuver succeeds, the damage will extend far beyond one council seat. It will send a message to every voter that their participation does not truly decide anything. It will teach losing factions that they can ignore pre election deadlines and wait to see how the numbers fall before deciding whether to raise eligibility arguments. It will undermine the legitimacy of every future election, because people will reasonably wonder whether the published result is the end or merely the beginning of a second, hidden contest waged in back rooms under the guise of legal interpretation.

This is not fairness. It is not legality. It is not due process. It is disenfranchisement dressed up as ethics. And Ohio’s own election jurisprudence has spent decades warning us about exactly this kind of post election manipulation.

V. The Calm Ends Here Because This Did Not Begin With Aden Fogel

Up to this point, this article has stayed focused on statutory text and case law. That was necessary, because the legal issues alone are enough to show that Sheffield Lake is out of bounds. But to understand how the city arrived at a place where it feels comfortable trying to undo a certified election, one has to look beyond the four corners of the Revised Code and examine the history of how power has actually been exercised inside Sheffield Lake government.

This did not begin with Fogel.

For years, Sheffield Lake has been governed by a culture in which rules are flexible for insiders and inflexible for outsiders. It is a culture in which overlapping roles, blurred lines of authority, and quiet structural adjustments have been used to concentrate power in the hands of a relatively small group. That culture is not speculative. It is documented in civil service rules, memoranda, ethics opinions, and appointment patterns that show how the city has repeatedly been willing to stretch or ignore structural safeguards when doing so benefited those already on the inside.

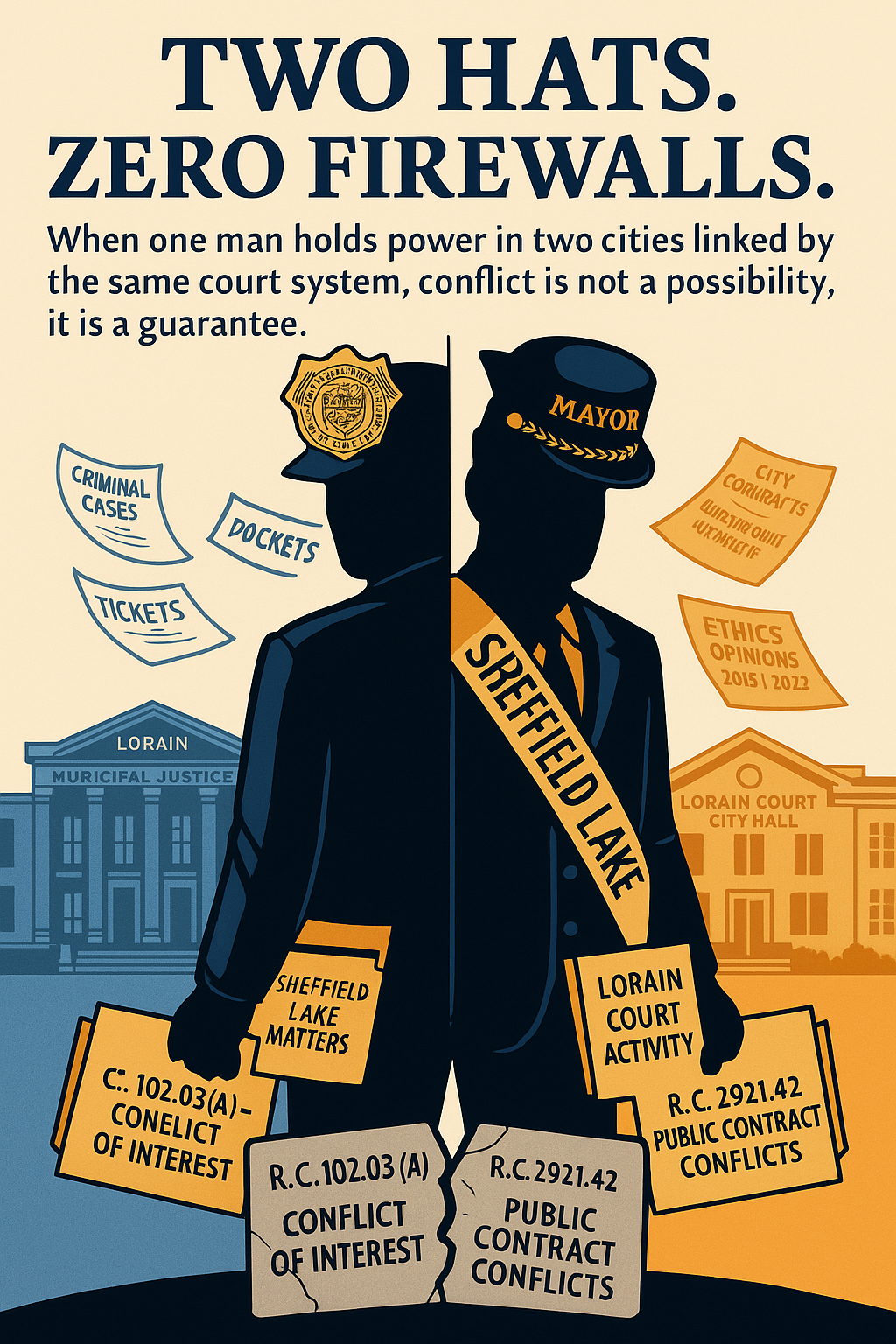

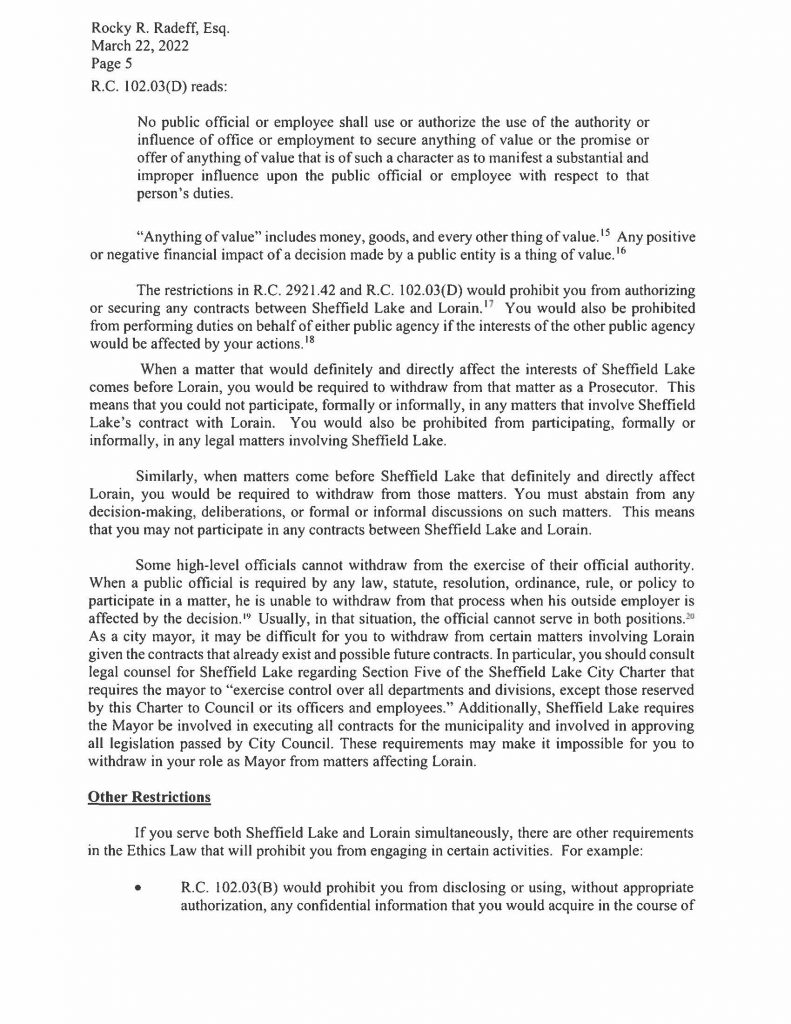

The period associated with Rocky Radeff is one of the most revealing. During that time, Radeff occupied multiple roles inside the city in a configuration that raised direct conflict of interest concerns under Ohio ethics law. Public officials are not supposed to wear several hats at once in ways that place them on both sides of the same decision. Yet the city allowed this structure to persist. Instead of disentangling the roles so that each had clear and independent lines of authority, the city rationalized the overlapping arrangement. The so called one hat rule, which exists to prevent exactly this kind of concentrated authority, was functionally ignored.

The era associated with David Graves followed a similar pattern of informal power flowing through personal networks rather than clear, transparent channels of authority. In that environment, access and influence often depended less on institutional position and more on proximity to the insider circle. Administrative decisions and political considerations became intertwined in ways that are difficult to justify under any model of neutral governance.

Taken together, these histories reveal a city that has grown comfortable treating structure as negotiable. Conflicts of interest rules became less like guardrails and more like obstacles to navigate around. Ethical boundaries became malleable for those who enjoyed favor and rigid for those who did not.

When that is the environment inside a government, it becomes much easier to see how a law director can decide, after the fact, that the city should reinterpret eligibility rules and attempt to undo a certified election. It is not that the law changed. It is that the same habits that once allowed overlapping roles and blurred lines to persist are now being applied to the democratic process itself.

The attempt to disqualify Fogel after a seventy two percent victory is not an isolated overreach. It is the predictable next step of a system that has long believed rules can be bent to protect its preferred configuration of power. The difference now is that the target is not a job assignment or an internal appointment. The target is the voters decision.

And that is what makes this moment different, and far more dangerous.

Aaron Knapp

VI. The Radeff Files: Ethics Warnings That Were Ignored While the Conflicts Deepened

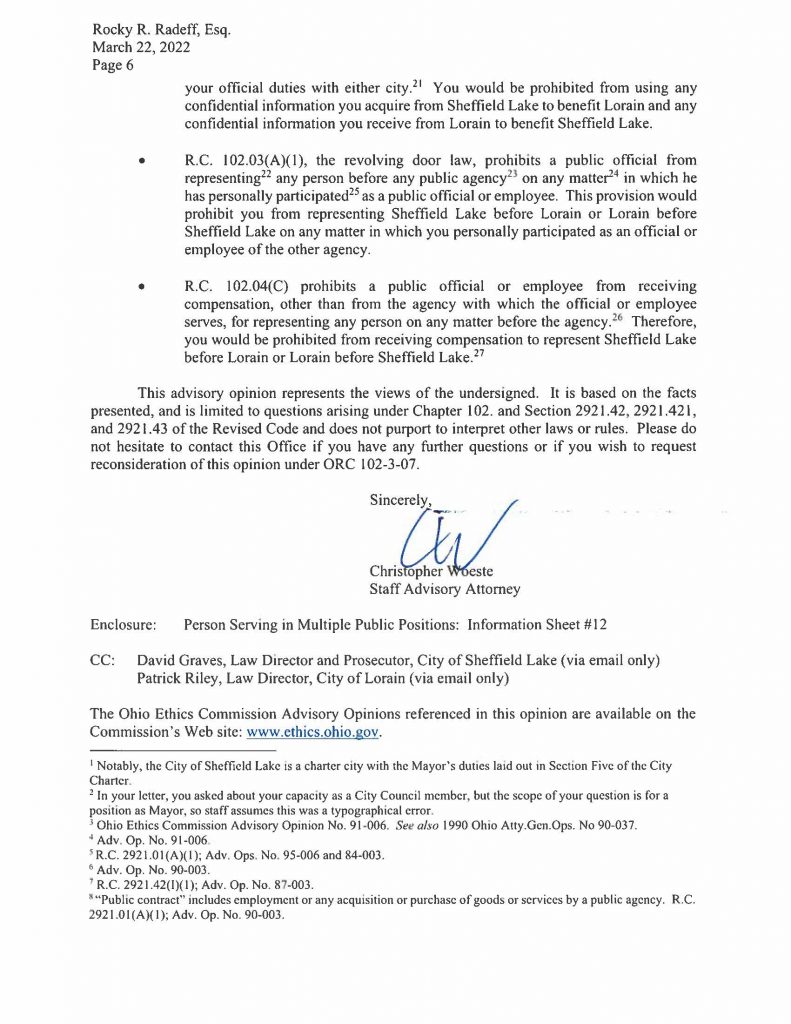

The ethics advisory opinions involving Rocky Radeff were not theoretical exercises or distant hypotheticals. They were issued while he was an active Sheffield Lake councilman, addressing concrete conflicts already present within the city’s governmental structure. These letters were written because he was simultaneously occupying roles and engaging in duties that placed him at the intersection of competing public responsibilities. The Ethics Commission made its concerns explicit. In 2018, it stated that a public official cannot serve in positions where the individual’s public authority overlaps with supervisory or employment ties that create an improper influence. In 2022, the Commission emphasized that continuing in such a dual arrangement would constitute a prohibited conflict of interest under R C 102.03, particularly when public authority could be used, intentionally or otherwise, to benefit a secondary role or external entity.

Despite these clear warnings, the structure of Sheffield Lake government remained largely unchanged. The overlapping duties persisted. The city did not create meaningful firewalls, did not restructure the positions, and did not treat the ethics analysis as binding guidance that required institutional correction. The conflict became part of the fabric of city governance rather than an issue to be resolved. The message was unmistakable. When conflicts implicated insiders, compliance with ethics law became optional.

These concerns were magnified by the deeper relationship between Sheffield Lake and the City of Lorain, especially through the Lorain Municipal Court. Sheffield Lake’s criminal and traffic cases are prosecuted and adjudicated in that court system, which means that prosecutorial decisions, charging judgments, and enforcement priorities flow through an institution that is not merely adjacent to Sheffield Lake but contractually and functionally intertwined with it. Any public official who simultaneously wields prosecutorial authority within the Lorain court structure and executive or policymaking authority in Sheffield Lake is not simply juggling two roles. They are embedded in a feedback loop where decisions made in one capacity can influence, and be influenced by, obligations in the other.

When Radeff later sought ethics guidance in connection with pursuing the mayor’s office, the request did not fully confront the implications of this arrangement. The opinion framed the issue broadly but did not directly address the fact that Sheffield Lake’s prosecutions are handled in Lorain’s municipal court, or that the individual seeking the opinion could find himself occupying positions of power in both systems simultaneously. The advisory did not explore how decisions made as mayor regarding policing, budgeting, interagency contracts, or enforcement priorities would intersect with the same court where he exercised prosecutorial authority. It did not examine how contracts between Sheffield Lake and Lorain, or agreements governing legal services, could create interests prohibited by R C 2921.42, which bars public officials from using their office to benefit from public contracts in which they have a direct or indirect interest.

The absence of this analysis is not a small omission. It goes to the core of what Ohio ethics law is designed to prevent. R C 102.03 restricts public officials from using public authority to secure anything of value that could create a substantial and improper influence upon them. It prohibits them from participating in actions where their personal, financial, or professional interests intersect with their official duties. R C 2921.42 goes further by prohibiting officials from having an unlawful interest in a public contract, including situations where an official’s secondary role is tied to an entity or system that contracts with or serves the public office they hold.

When a city relies on another municipality’s court system for its criminal prosecutions, and a single individual is simultaneously positioned to influence both systems, the conflict is not theoretical. It is built into the structure. Every enforcement decision in Sheffield Lake, every discussion about contracts with Lorain, every policy relating to policing, budget allocations, or legal services becomes intertwined with the official’s prosecutorial interests in Lorain’s court. The official stands at the convergence of multiple streams of governmental authority that ethics law was specifically written to keep separate.

This is not merely a close call. It raises the very concerns that the ethics opinions warned about years earlier. When those warnings first appeared, they were not taken seriously. Instead of restructuring the roles or removing the overlapping authority, the city allowed the arrangement to deepen. And now, that same governmental culture is attempting to portray itself as rigidly bound by law when dealing with a councilman elect chosen overwhelmingly by the voters.

The inconsistency is striking. When ethics rules limited insiders, the rules were minimized or ignored. When statutory deadlines limited the city’s ability to remove an outsider, those deadlines were treated as irrelevant. But the moment an outsider wins seventy two percent of the vote, the same city claims it is legally compelled to take action against him because of an ethics or eligibility framework that does not actually apply. This is not principled governance. It is the selective invocation of law to preserve an existing power structure.

The hypocrisy becomes even clearer when considering the ethical implications of a mayor simultaneously connected to a prosecutorial system that directly serves his own city. If one were to apply the same strict standard Sheffield Lake is now attempting to impose on Fogel, the individual pushing this disqualification effort would himself be the first person barred from taking office. Far from standing on high legal ground, he is positioned squarely in the kind of conflict of interest that Ohio law treats with the greatest concern. Under the plain language of R C 102.03 and R C 2921.42, combined with the documented intergovernmental relationships between Sheffield Lake and Lorain, he is operating in a landscape where divided loyalties are not only possible but structurally embedded.

When one examines this context, the city’s sudden commitment to rigid legal interpretation appears less like fidelity to ethics and more like strategic convenience. The law becomes flexible when insiders benefit and uncompromising when outsiders win the support of the electorate. That is not the rule of law. It is the rule of selective enforcement, and it is the logical continuation of the same patterns identified in the Radeff ethics opinions years before.

LEGAL SIDEBAR: Why the Mayor Role and Prosecutorial Role Are Incompatible in Sheffield Lake

Ohio law is not vague about the dangers of a single official sitting on both sides of the same stream of power. The Ohio Revised Code draws firm lines around conflicts of interest, public contracts, and overlapping duties, especially when those duties touch law enforcement and the courts. Those lines exist to prevent divided loyalties, self dealing, and structural bias from corrupting the operation of government. When a mayor in Sheffield Lake is also tied into the prosecutorial machinery of the Lorain Municipal Court, those lines are not just brushed against. They are crossed.

The conflict begins with R C 102.03, Ohio’s central ethics statute for public officials. This law prohibits a public official from using the authority or influence of their office to secure anything of value that could have a substantial and improper influence on the official with respect to their public duties. It also restricts officials from participating in matters where their private interests or secondary roles conflict with their public responsibilities. Ohio ethics training materials and outlines frame this as a bright line rule. An official must not use the public position to benefit themselves, their outside employer, or any entity with which they have a personal or financial tie. The statute is preventative. It does not wait for an actual payoff to occur. The existence of a conflicting role is enough to require the official to step back. Ohio Laws+2Ohio Laws+2

Layered on top of that is R C 2921.42, the criminal prohibition against having an unlawful interest in a public contract. Under this statute, a public official is forbidden from knowingly authorizing, negotiating, or having an interest in a public contract that involves the governmental entity they serve when the official stands to benefit from it financially or professionally. Violations can constitute a felony or misdemeanor depending on the division violated. The Attorney General and Auditor of State have repeatedly emphasized that this statute is meant to bar officials from sitting on both sides of a contract, either directly or through outside positions that give them a stake in how that contract is structured or enforced. Ohio Attorney General+3Ohio Laws+3Ohio Laws+3

Then there is the jurisdictional framework created by R C Chapter 1901 for municipal courts. Lorain Municipal Court is not just another court somewhere out in the state. By statute, it has territorial jurisdiction over the City of Lorain, the City of Sheffield Lake, and Sheffield Township. That means criminal and traffic cases arising in Sheffield Lake are heard in Lorain Municipal Court, and that the court’s daily work includes enforcing ordinances and misdemeanor laws that directly affect Sheffield Lake residents. The city’s own materials and annual reports confirm that Sheffield Lake is part of the Lorain Municipal Court district. City of Lorain+5Ohio Laws+5Ohio Laws+5

When those three pieces are placed together, the incompatibility of a combined mayor and prosecutor role comes into focus. A mayor in Sheffield Lake has executive authority over policing priorities, budget allocations, departmental oversight, and intergovernmental relationships, including any agreements related to court services and law enforcement. A prosecutor in Lorain Municipal Court has authority over charging decisions, plea negotiations, sentencing recommendations, and the handling of every criminal and traffic case that comes through that court from Sheffield Lake. If the same person sits in both chairs, that person is simultaneously setting the policy that determines how Sheffield Lake residents are policed and appearing in court as the legal voice of the state in cases that flow from those policies.

That situation invites multiple conflicts under R C 102.03. When the mayor decides whether to expand enforcement of particular ordinances, fund certain policing initiatives, or support specific intergovernmental agreements, the prosecutor side of that same individual has an interest in how those decisions will shape their caseload, courtroom leverage, and professional standing. When the prosecutor decides whether to push for higher fines, greater use of certain charges, or specific plea structures, the mayor side of that same individual has an interest in the resulting revenue streams, political optics, and departmental outcomes. The public cannot be expected to believe that these decisions are insulated from each other when they are housed in the same person.

R C 2921.42 sharpens this concern wherever there are contracts or formal arrangements connecting Sheffield Lake to Lorain. Municipal courts rely on statutory cost allocations and, often, intergovernmental understandings about how costs, fees, and services are shared. Lorain Municipal Court’s own reports describe how it collects and distributes money for the city, for the county, and for state programs in connection with its caseload. When Sheffield Lake residents are processed through that court, the financial and operational consequences of those cases are intertwined with the contracts and arrangements between the jurisdictions. A mayor who influences or approves those arrangements, while also working inside the court structure that administers them, risks falling squarely into the zone that 2921.42 was written to police. City of Lorain+2City of Lorain+2

The incompatibility is not limited to money. It goes to the integrity of the justice system itself. A mayor who oversees or influences the police department may also have access to information, strategy, or pressure points that are relevant when those cases reach court. If that same individual is involved in prosecution, the distinction between independent executive oversight and courtroom advocacy collapses. The public must be able to trust that charging decisions are made based on law and evidence, not based on how a mayor wants to shape statistics, please allies, punish critics, or manage political narratives.

Ohio’s ethics law was designed to keep these roles apart. The Ethics Commission, in its training materials and outlines, explains that public officials must avoid any outside employment or secondary role that is incompatible with the proper discharge of their duties or that would tend to impair their independence, judgment, or action. Conflicts do not always announce themselves with a bag of money on a table. Often, they appear exactly in these kinds of structural overlaps, where the same person quietly occupies two roles that pull in different directions. American Legal Publishing+3Ohio Auditor+3Sopec Ohio+3

When one looks at a mayor who is simultaneously tied into the prosecutorial structure of the very court that serves his city, while that court’s territorial jurisdiction and financial operations are bound up with the fate of his constituents, it becomes hard to imagine a cleaner example of what the conflict of interest statutes are meant to prevent. The dual roles do not merely raise abstract questions. They cut directly against the independence required of both the executive and the judicial arms of local government. Under the spirit and the text of R C 102.03 and R C 2921.42, a Sheffield Lake mayor linked into Lorain Municipal Court prosecution is not standing near a gray area. He is planted squarely in the middle of an ethics minefield.

Seen against that backdrop, the city’s attempt to invoke ethics language to remove a councilman elect whose past does not fall within Ohio’s specific disqualification statutes is not a display of high principle. It is a selective deployment of legal rhetoric by a system already balancing on its own unresolved conflicts. The law that is being waved like a banner in one direction is being stepped on in another. That is why the incompatibility of the mayor and prosecutorial roles is not a side note in this story. It is the core of the hypocrisy that makes the Fogel disqualification effort so offensive to both law and basic fairness.

VII. The Living Insider Network: How Radeff and Graves Still Shape Power in Sheffield Lake

To understand why the Fogel disqualification effort is unfolding the way it is, one must understand that Sheffield Lake does not operate through the formal machinery described in its organizational charts. It operates through something older, more entrenched, and far more difficult to confront. It operates through a living insider network that continues to shape who holds influence, who has access, who gets protected, and who gets targeted. This network is not theoretical. It is visible in the documents, the patterns, and the decisions that continue to circulate through City Hall. And two figures stand at the center of this structure: Rocky Radeff and David Graves.

The ethics opinions related to Radeff were issued because he held overlapping public and private roles that fundamentally conflicted with the duties imposed by R C 102.03. The Ethics Commission was not issuing an abstract warning. It was responding to a real conflict that existed inside Sheffield Lake and that continues to echo today. The Commission made it clear that a public official may not use the authority of their office to influence matters where they have personal or supervisory interests. It made it clear that dual roles create impermissible conflicts when public duties intersect with private obligations. And it made it clear that such conflicts impair independence and create opportunities for undue influence.

Yet despite these warnings, the system was not untangled. It was normalized. The overlapping roles remained, the structure survived, and the culture adjusted around it. That culture is still present. It continues to shape how the city operates and how decisions are made.

This continuity becomes even more evident when examining the ongoing role of David Graves. His name is not incidental in the city’s documentation. It appears in the internal record with a consistency that reveals a deeper truth about the city’s actual governance structure. It shows up in memos, facility logs, procedural notes, administrative decisions, interdepartmental communications, and operational materials that do not belong to any single lane of authority. It appears in reference chains where he is not merely receiving information but influencing its direction. His involvement is not passive. It is threaded through the daily machinery of City Hall.

He is still there. He is still active. He is still appearing in places where the authority should be exercised by elected officials or top-level administrators. In some cases his involvement appears in areas that directly intersect with ethics restrictions placed on others. In other cases it appears in the points where discretionary judgment is exercised behind the scenes. The pattern is unmistakable. Graves functions as a stabilizing axis within the insider network, a point through which information moves and decisions are influenced, regardless of what the official hierarchy suggests.

When those two legacies, the Radeff conflict and the Graves operational influence, are placed side by side, a portrait emerges of a city that has grown accustomed to a system where internal alignment matters more than formal structure. Decisions are made not simply through ordinances or administrative processes but through the internal dynamics of individuals who have held influence for years and who continue to shape the culture regardless of official titles.

This environment explains more than internal politics. It explains why certain rules are enforced fiercely against outsiders and selectively against insiders. It explains why binding ethics warnings were absorbed and then disregarded. It explains why overlapping roles were maintained despite statutory prohibitions. It explains why key administrative decisions often appear to be coordinated within a small circle. And it explains why the attempt to remove Fogel feels less like a legal action and more like a coordinated response to an electoral disruption.

A system that has long relied on internal continuity will inevitably perceive an outsider, especially one chosen decisively by the voters, as a threat. The insider network has been accustomed to moving decisions through informal channels, leveraging relationships, and shaping outcomes without public confrontation. The arrival of a council member elected by seventy two percent of the vote disrupts that flow. It introduces a variable the internal system did not select. And in that disruption, the instinct is not adaptation. The instinct is resistance.

This is why the disqualification effort must be understood through the lens of the insider network. It is not merely a misinterpretation of law. It is the system attempting to reassert control by invoking a statute that does not apply, constructing a barrier that does not exist, and framing a decades-old felony as an urgent legal crisis only after the voters expressed a preference that diverged from the internal network’s expectations. It is the same pattern observed in the ethics cases involving structural conflicts. It is the same pattern observed in the ongoing administrative role of Graves. It is the same pattern observed in the city’s prior response to political criticism during the Morrow incident. It is the system reacting to the loss of control over an outcome it did not engineer.

The insider network did not disappear after the ethics advisories. It did not dissolve as new elections occurred. It did not fade as personnel changed titles. It adapted. It persisted. And it continues to operate today in ways that make the attempted removal of Fogel not only predictable but inevitable. The city’s relationship with its own rules is shaped by who benefits from those rules at any given time. When the rules protect insiders, they are treated as authoritative. When the rules constrain insiders, they are treated as flexible. When the voters impose a result the network did not choose, the network attempts to impose a correction.

In Sheffield Lake, the conflict over Fogel is not a legal dispute. It is a collision between democratic legitimacy and an internal system accustomed to operating without meaningful challenge. The documents that record the roles of Radeff and Graves reveal a pattern of governance that exists outside the formal structures of law. The voters disrupted that pattern. The network is trying to restore it. And the disqualification attempt is the mechanism through which that restoration is being attempted.

This is the environment in which the Fogel controversy exists, and this is the context that makes the city’s actions not only troubling but revealing. The insider network is still alive. It is still functioning. And it is still willing to reinterpret rules to maintain its continuity.

VIII. The Continuity of Abuses: The Morrow Letter and the Blueprint for Targeting Fogel

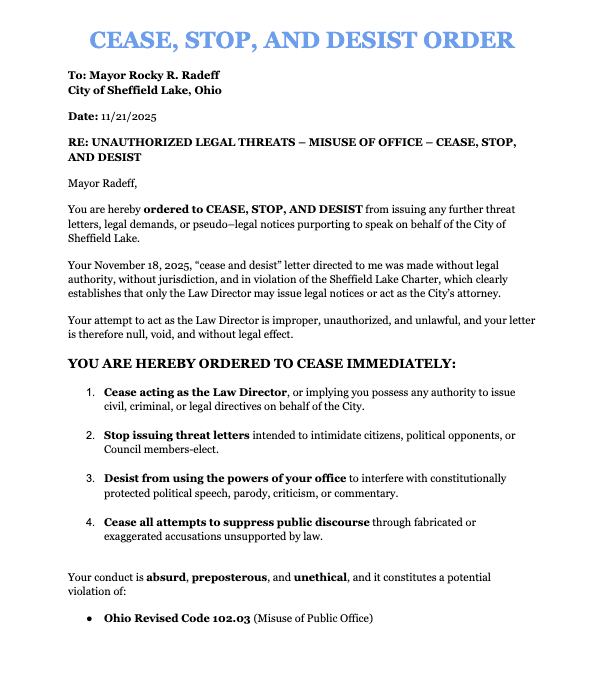

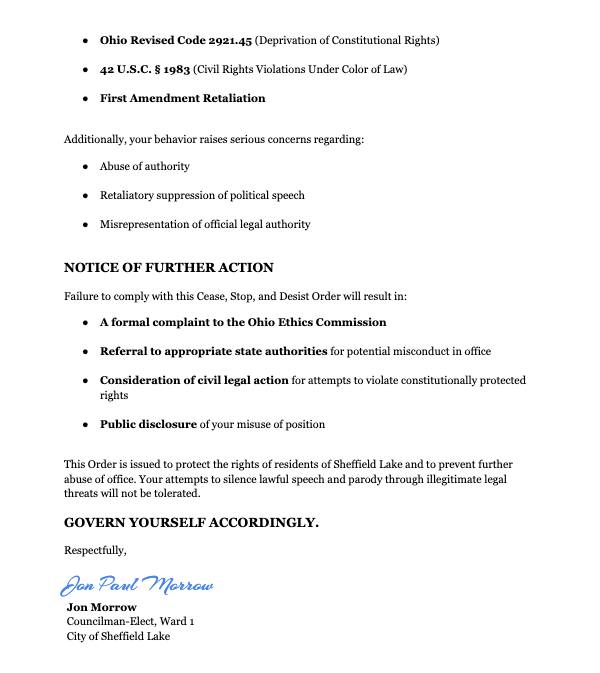

The attempt to remove Aden Fogel from office becomes far easier to understand when viewed against the backdrop of another recent episode, one that laid bare the city’s willingness to escalate political disagreement into legal confrontation. That episode involved Councilman-elect Jon Morrow, a website he created, and a cease-and-desist letter sent by Mayor Rocky Radeff that revealed a stunning willingness to brand protected political speech as criminal conduct when it served the interests of those in power.

The conflict began with a simple website. Morrow created an online platform, sheffieldlake.community, which he openly described as a work of irony and a civic forum for residents to evaluate city leadership and propose ideas for improvement. It had been available to the public for more than a year without any objection from the city. It was public, unhidden, and unmistakably political. Nothing about it resembled deception. Nothing about it suggested fraud. Nothing about it implied an attempt to impersonate the city.

Only when Morrow posted a survey asking residents to evaluate the mayor’s performance and to indicate whether he should be recalled did the city suddenly respond with accusations of criminality. The mayor sent a formal cease-and-desist letter on behalf of the city that read less like a cautionary note and more like an indictment. It accused Morrow of intentionally misleading the public. It alleged that his website was designed to resemble an official city page. It claimed that residents were at risk of identity theft and financial loss. It suggested that Morrow’s survey was an unauthorized collection of personal data. And it warned that failure to take down the site within ten days would leave the mayor no choice but to pursue all available civil and criminal remedies.

The letter cited potential violations such as identity fraud, telecommunications fraud, unauthorized use of personal data, and computer fraud and abuse. The tone and content of the letter created a clear impression that Morrow’s criticism was not merely unwelcome but potentially illegal, and that the city was preparing to brand his political activity as criminal misconduct. It was a communication designed to intimidate. It was a communication designed to chill speech. And it was issued in the middle of an election in which Morrow was a candidate.

If any part of the accusation were sincere, the city would have pursued it. It did not. Instead, the mayor reversed course after Morrow made only two minor cosmetic changes to the site: replacing a phrase and adding a photo to a disclaimer. The survey remained unchanged. The website continued to ask residents whether the mayor should be recalled. And with those superficial modifications, the mayor declared that the concerns had been resolved.

Nothing about the stated threats made sense if the allegations were genuine. If the mayor truly believed the site endangered residents or violated criminal statutes, then cosmetic adjustments would not eliminate the supposed risks. If identity theft or data misuse were real possibilities, the city would have acted on those concerns. The reversal revealed what the threat actually was: a political weapon disguised as legal enforcement.

The Case Western Reserve University First Amendment Clinic reviewed the letter and the website and concluded that the mayor’s threat had no basis in law. The content was protected political speech. The disclaimer was sufficient to prevent confusion. And even without a disclaimer, the site would still have been protected under the First Amendment. The statutes cited by the mayor did not apply. They were invoked in a way that was legally unsound and constitutionally impermissible.

This episode did not fade into obscurity. It became part of the living structure of governance in the city. It revealed how the administration responds when criticism emerges from outside the insider network. It showed how quickly political dissent is reframed as misconduct. It demonstrated that the use of legal language in Sheffield Lake often mirrors the use of internal rules: flexible toward insiders and weaponized toward outsiders.

In this context, the attempt to remove Fogel follows the same blueprint. Fogel is not being targeted because the statutes require his removal. He is being targeted because he enters the government without the blessing of the internal network and because the voters elevated him with a level of support that made him impossible to ignore. His victory was not narrow. It was overwhelming. It represented a rejection of the insider structure’s preferred direction, and in that rejection, the system reacted.

The same city that insisted Morrow’s satire was fraud now insists Fogel’s decades-old conviction renders him uniquely dangerous to the public trust, despite the fact that Ohio law clearly permits individuals with past felony convictions to run for and hold municipal office unless the offense involved public corruption. The same city that ignored ethics warnings when they constrained insiders now claims to be bound by legal purity when the law protects an outsider. The same leadership that retracted a legally indefensible threat only after public scrutiny now advances a legally indefensible disqualification theory because the voters selected someone who did not emerge from inside the network.

The Morrow incident was not an isolated mistake. It was a preview. It demonstrated how the system reacts to political threats, how it reframes criticism as criminality, and how it uses the language of law to pursue outcomes that have little to do with the law itself. It established the pattern. Fogel’s disqualification is the next iteration of that pattern, not an independent event. It is a continuation of a strategy that regards the ballot box as a variable to be managed rather than a decision to be respected.

Seen through this lens, Fogel was an obvious target, not because the law disqualifies him, but because his election disrupted a network that has long operated without challenge and without accountability. The Morrow incident provided the blueprint. The Fogel dispute is the execution.

IX. Legal Endgame: When Policy Opposition Turns Into Legal Warfare

The question now is not simply whether the technical arguments for removing a duly elected councilman hold up under Ohio law. The more fundamental question is this: what does the push to disqualify Aden Fogel, in the wake of the Morrow cease-and-desist fiasco, actually represent? Viewed through the lens of how local power is wielded in Sheffield Lake, the legal arguments are just the tip of a deeper strategy. This is not law enforcement. This is political enforcement.

A City Divided by Redevelopment — and Who Happens to Oppose It

For more than two years, the top of Sheffield Lake’s agenda has been a sweeping redevelopment plan, championed by long-time insiders. The proposals have involved major zoning changes, new development contracts, public-private partnerships, revisions to city ordinances, and reallocation of tax and service revenues. The insiders have framed these initiatives as an economic salvation plan — but several council members and community activists have emerged as outspoken critics. Among them are two men: the recently elected councilman Aden Fogel and the other recently elected Councilman Jon Morrow whose online platform drew the ire of the mayor.

These men consistently opposed key aspects of the redevelopment agenda: the transfer of public infrastructure under long-term contracts, the privatization of municipal services, changes to the civil service rules favoring “contracted management,” and the loosening of transparency controls around city-vendor relationships. Their opposition was public, well-documented in city council minutes, and amplified in door-to-door canvassing, public forums, and online criticism.

Because they resisted — loudly, repeatedly, and effectively — they became inconvenient anomalies inside a system primed to run on compliance, not conflict. In that context, the effort to strip them of office or chill their speech with threats is not legal ambiguity. It is political survival.

The Dual Levers: Legal Threats and Eligibility Laws

When a political network is strong enough to embed itself across executive, prosecutorial, and administrative layers, the tools for controlling dissent expand beyond persuasion and persuasion’s milder cousin, outreach. They come to include legal pressure, institutional gatekeeping, and selective application of eligibility standards. The same mechanisms that were once used to protect insiders now appear ready to regulate, retroactively, who may hold office.

The cease-and-desist letter sent to Morrow displayed the first lever in action: turn public criticism into criminal threats, using overbroad legal language about fraud and data misuse to attempt to silence dissent. When that failed under public scrutiny, the network paused, recalibrated, and deployed the second lever: eligibility law. Now the target is Fogel, whose record the insiders hope will survive being framed as disqualifying, despite precedents and relevant statutes. Their hope is that by keeping the threat alive — even if unlikely to succeed, the mere cloud of legal jeopardy will intimidate others from opposing the redevelopment agenda in the future.

Why the Courts Must Resist This Legal Weaponization

Ohio’s election law and public-office statutes were never written to grant political insiders a do-over after a landslide loss. They were written to preserve voter choice, to enforce clear disqualification only where public corruption or office-related crimes occur, and to prevent charges of impropriety from being used as political cudgels.

If the courts permit Sheffield Lake’s current effort, to unseat someone based on a decades-old conviction unrelated to public office, after the election has already been certified, they will effectively sanction a new form of political control: the indefinite eligibility challenge. That would empower any local government to subvert electoral results not through persuasion at the ballot box, but through legal intimidation afterward.

By doing so, they would not uphold Ohio law. They would enable a new precedent of retroactive political disqualification, undermining both the letter and spirit of democratic representation, and opening the door for abuse under every possible political realignment.

The Stakes for Sheffield Lake, and Beyond

If this attempt fails, if courts recognize what the law plainly states and demand election finality, the redevelopment agenda must compete on substance, not leverage. Constituents will have the opportunity to cast votes, public hearings will have meaning, and transparency will once again matter.

If this attempt succeeds, or even remains viable, Sheffield Lake will become a case study not of civic progress, but of how power can be maintained by legal architecture. It will signal that electoral wins can be undermined not by public debate but by private strategy; that contracts and court relationships can insulate insiders; and that the voters’ will can be reversed by lawyers, not ballots.

That is not governance. That is gatekeeping.

X. Final Thought: The Pattern Is Bigger Than Sheffield Lake

For the past two years, I have been writing about the quiet but unmistakable erosion of accountability in local government, beginning first in Lorain and then expanding outward as patterns emerged that were simply too consistent to ignore. What is happening in Sheffield Lake is not an isolated political spat. It is not a one-off dispute over an eligibility statute or a disagreement about a website. It is part of a broader regional pattern that stretches across municipal borders and connects directly to the same institutions, the same personalities, and the same structural failures that have already caused massive harm in Lorain.

The parallels are impossible to miss. In Lorain, I wrote extensively about the misconduct tied to the Lorain Municipal Court, a court that spent months issuing hundreds of illegal parking citations, suspending the driver’s licenses of residents who had committed no crime, and generating revenue through an enforcement scheme that had no lawful basis. More than six hundred people were penalized under a system that should never have existed. Their licenses were suspended. Their fines were collected. Their records were damaged. All of it was unlawful. All of it was avoidable. And all of it was upheld by silence until these abuses finally came to light.

That same court is the court where Sheffield Lake Mayor Rocky Radeff serves as a prosecutor.

That is the part no one wants to say out loud. That is the part that connects these stories. When I covered the Lorain illegal ticket scandal, I wrote about how that court’s structural flaws created a system that punished citizens without legal authority, and how the internal actors involved continued operating without meaningful oversight. Those patterns mirror what is now happening in Sheffield Lake: government actors wielding law not as a standard to follow, but as a tool to direct at those who stand in their way.

Whenever a political system becomes accustomed to bending rules for insiders, it eventually begins bending rules against outsiders. The Lorain Municipal Court bent rules to generate revenue. Sheffield Lake is now bending rules to preserve political power. The mechanics differ, but the philosophy is the same. It is governance by convenience. It is accountability by selectivity. And it is legality by interpretation rather than legality by statute.

Aaron Knapp

The same court that unlawfully suspended licenses now sits at the intersection of the mayor’s influence and the city’s prosecutorial apparatus. The same court that operated without correction now forms part of the ethical terrain through which Sheffield Lake’s leadership navigates conflicts, political disputes, and intergovernmental relationships. And now, that same structure is being used as the backdrop to justify why a man the voters overwhelmingly selected should be denied the seat they chose him to hold.

When the Lorain ticket scandal broke, the city tried to pretend it was an administrative accident. But the documents told a different story. They told a story about a system that had come to believe it did not need to follow the rules because it assumed no one would ever challenge it. The same assumption is at work in Sheffield Lake. The insiders believe they can reinterpret eligibility law. They believe they can weaponize cease and desist letters. They believe they can reframe political criticism as fraud. And they believe they can erase seventy two percent of the voters if they can construct a narrative to make it sound legal.

This is why the fight over Fogel matters. It matters not just for Sheffield Lake but for everyone who lives within the reach of a municipal system that has grown too comfortable with its own power. It matters because the same people who oversaw a court that issued hundreds of unlawful penalties now claim to be guardians of legal purity. It matters because the same structures that ignored ethics warnings about overlapping roles now insist that they must intervene to protect the public trust from a conviction that occurred decades ago. And it matters because the same system that tried to intimidate Morrow with invented criminal allegations is now trying to erase the will of the voters with invented interpretations of election law.

I have written about these issues because they are not confined to one city or one official. They are symptoms of a larger pattern in which municipal power has ceased to be transparent and has begun to operate for its own preservation. What is happening in Sheffield Lake is tied to what has been happening in Lorain. What is happening in the court is tied to what is happening in City Hall. And what is happening to Fogel is tied to what has happened to every resident who ever found themselves at the mercy of a system that had forgotten who it was supposed to serve.

In the end, the law is not complicated. The statute is clear. The voters spoke. The election was certified. And nothing in Ohio law authorizes the city to undo what the people decided. The only thing complicating this is the same thing that has complicated every abuse I have documented: the will of those in power to reshape the rules whenever the public refuses to cooperate.

The voters of Sheffield Lake chose their councilman. The city now has a choice of its own. It can accept the result of a democratic process, or it can continue down the path already worn into place by redevelopment interests, insider networks, and a court system that has already shown the public what happens when the rules are treated as suggestions.

This is also where I need to be transparent with readers. I have not been some long-time defender of either Jon Morrow or Aden Fogel. In fact, I have been publicly critical of both of them. I have disagreed with things they have said. I have pushed back on their comments. There was a period where I had Fogel blocked, and for personal reasons I wanted nothing to do with him. Only recently, after he apologized for things he said online, did I unblock him and set that aside. I did that because I am a man of my word and because I believe in correcting course when someone extends genuine effort to make amends.

But none of my past disagreements change the truth in front of us. They do not change the law. They do not change the vote totals. They do not change the fact that what Sheffield Lake is doing is wrong.

Some people will try to twist this into a matter of alliances or loyalties, but that is not what this is. This is about a city government attempting to undo an election because it did not like the outcome. This is about power, not principle. This is about a political network using legality as a weapon after the voters refused to cooperate.

And my personal history with either of these individuals does not diminish the seriousness of what is unfolding. If anything, it underscores it, because I am saying all of this not out of friendship, not out of preference, and not out of political alignment, but because the truth is the truth even when it comes wrapped in people you once fought with.

There is no escaping the reality of what is happening here. The law is not complicated. The statute is clear. The voters spoke. The election was certified. And nothing in Ohio law authorizes the city to undo what the people decided.

There is only the question of whether the law will win or whether familiarity will. And that, more than any legal theory, is the real test Sheffield Lake is now facing.

Legal & Editorial Disclaimer

This article is grounded exclusively in publicly available government records, Ohio Ethics Commission advisory opinions, statutory provisions, administrative rules, certified court filings, election-law materials, and archival documents obtained through lawful public-records requests. It reflects the author’s independent analysis, investigative commentary, and journalistic conclusions drawn from those materials. It is not, and should not be interpreted as, legal advice, legal representation, or instruction on how to pursue or defend any legal claim. Readers should consult qualified legal counsel for any matter requiring legal interpretation beyond the scope of public commentary.

Nothing contained herein asserts or implies that any named individual has committed a criminal offense, civil violation, ethical breach, or administrative infraction unless such finding has been formally rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction or an authorized investigative body. All individuals referenced in this article are presumed innocent unless and until proven otherwise in a court of law, and any allegations described are based solely on documented records, public statements, or official actions as reflected in the public domain.

This article is protected as journalistic speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution, and applicable case law governing public commentary on governmental affairs, public officials, and matters of public concern. Any errors of fact will be corrected upon verification.

AI USE DISCLOSURE

This article was drafted with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools to help organize information, research statutes and cases, and structure the narrative. All conclusions, interpretations, and editorial choices are solely those of the author.

To understand why the Fogel disqualification effort is unfolding the way it is, one must understand that Sheffield Lake does not operate through the formal machinery described in its organizational charts. It operates through something older, more entrenched, and far more difficult to confront. It operates through a living insider network that continues to shape who holds influence, who has access, who gets protected, and who gets targeted.

As an Example:

Fogel helped Mauricio.

Knapp helped Mauricio.

Petty helped Mauricio.

Radeff involved himself as prosecutor against Petty despite knowing that Riley and Zaleski were both witnesses.

Radeff (prosecutors & Staff) failed to provide Brady (exculpatory evidence in Petty criminal prosecution) choosing to hide and conceal evidence that was required to be disclosed. Radeff was peacefully confronted in the Public hallway, and there and then, he refused to shake Petty’s offered handshake nor apologize for the deliberate and intentional behavior of a cabal of politicians and scheming individuals who sought to misuse the LMC and police and prosecution machinery they themselves thought they could use to silence a critic and make him a criminal.

Radeff’s demonstrated F…Y… moment in the public hallway was evidently a demonstration of his true colors and a blatant display of his loyalty not to his role as a minister of JUSTICE, but as an assassin to the Rule of Law!

Is there really any doubt left as to how and why the Contempt controversy and the devised scheme for money-making parking tickets and driver’s license suspension debacle has been propagated under the conflicted watch of those installed for purposes other than to act as guardians of, for, and by The People?

Radeff and Riley and the other members of the orchestra are playing musical instruments but these musicians are ethically challenged and are not facing the music, nor playing the music of Justice.

Exposure of their behaviors may well bring about needed changes, scrutiny, and charges necessary and called for to rebuke them.

Moral of the story, when you refuse a handshake to an individual you have sought to actively harm, appreciate your witnessed behavior especially when your on camera in a public hallway. When will the conflicts be addressed and resolved?