The Barilla Judgment and What the Court Actually Found

How a Public Records Mandamus Case Exposed Deliberate Withholding, Escalating Liability, and the Real Cost of Treating Transparency as Optional Governance in Lorain County

By Aaron Knapp

Investigative Journalist

Founder, Unplugged with Knapp

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

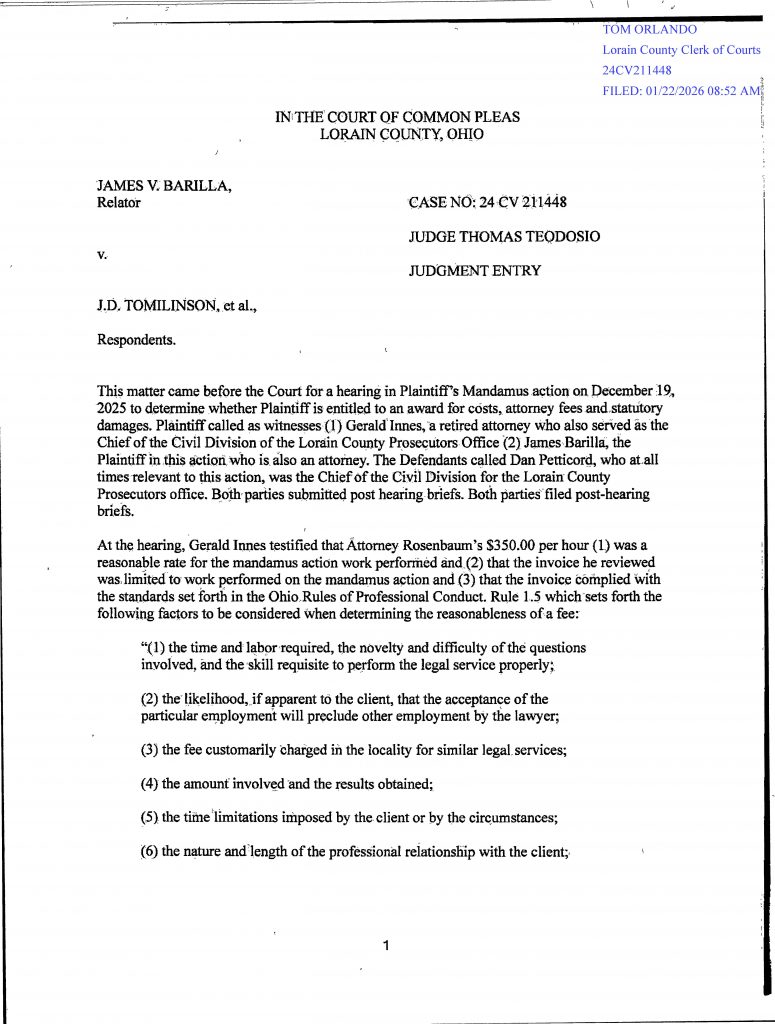

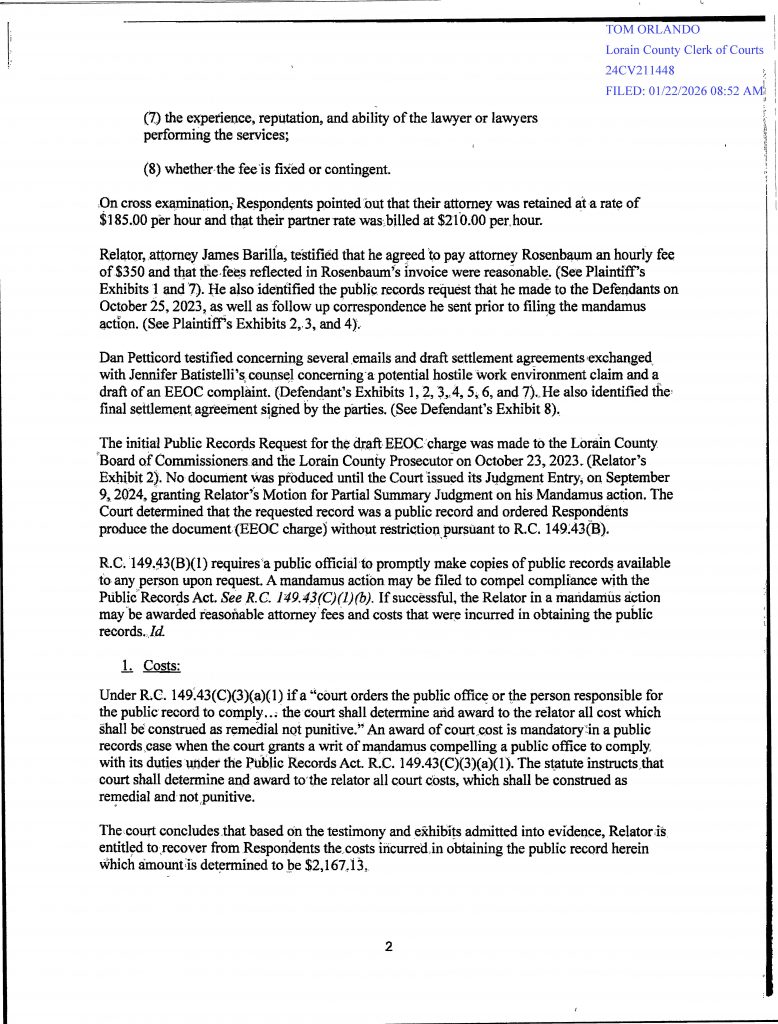

On January 22, 2026, a visiting judge entered judgment against Lorain County in James V. Barilla v. J.D. Tomlinson, et al., Case No. 24 CV 211448, a public-records mandamus action that never should have existed in the first place. The case arose from the County’s refusal to produce a draft EEOC complaint, a document the court found to be a public record as a matter of law. The procedural posture matters. This was not an emergency ruling or a paper decision. The court conducted a full evidentiary hearing, heard sworn testimony, reviewed exhibits, and then issued a detailed judgment entry that left no ambiguity about what happened or why the County lost.

The court’s findings were direct and unambiguous. It found that the requested document was a public record under Ohio law, that it was wrongfully withheld, and that mandamus relief was required to compel compliance. The court then applied Ohio Revised Code 149.43(C) exactly as written, awarding the relator costs, reasonable attorney fees, and statutory damages. There was no suggestion that the law was unsettled or that the County was navigating a gray area. The court found the violation and imposed the statutory consequences that follow when a public office refuses to comply with a mandatory disclosure obligation.

The final judgment ordered Lorain County to pay $2,167.13 in costs, $30,000.00 in reasonable attorney fees, and $1,000.00 in statutory damages.

The final judgment ordered Lorain County to pay $2,167.13 in costs, $30,000.00 in reasonable attorney fees, and $1,000.00 in statutory damages. In doing so, the court made findings that are especially damaging to any claim that this outcome was unavoidable. The court expressly found that relator’s counsel reasonably expended 120 hours litigating the mandamus action, that the hourly rate charged was consistent with fees customarily charged in Lorain County for comparable legal services, and that the work performed was necessary only because the County chose not to comply when it was legally required to do so. This was not a fee windfall. It was compensation for time the court found should never have been required.

This was not a close call, and the record proves it. Months before the final judgment, the court had already granted partial summary judgment in favor of the relator, explicitly finding that the County improperly withheld the requested record and ordering its production. At that point, the County had a clear off-ramp. It could have complied, produced the document, and substantially limited its financial exposure. Instead, it chose to continue litigating, to defend a position the court had already rejected, and to force additional motion practice and hearing time. The result was entirely predictable. The County lost again, this time on attorney fees, precisely because it refused to stop when the law told it to stop.

The legal significance of this judgment cannot be minimized. Under R.C. 149.43(B), compliance with a public-records request is mandatory, not discretionary. Once a public record is requested in a manner that reasonably identifies it, a public office has an affirmative duty to promptly produce that record. The statute does not allow delay because disclosure is embarrassing, politically inconvenient, or damaging to internal narratives. It does not authorize a public office to withhold records to manage fallout or to protect officials from scrutiny. When a public office violates that duty and forces a requester to file a mandamus action, R.C. 149.43(C) requires courts to award costs and authorizes the award of attorney fees and statutory damages. The court’s fee award here was not punitive. It was remedial, exactly as the statute directs, designed to place the financial burden of noncompliance where the law says it belongs, on the public office that refused to follow it.

In plain terms, this loss was optional.

In plain terms, this loss was optional. The County was not trapped by unclear law or unforeseen consequences. It was warned by the statute, warned by prior case law, and warned again by the court’s partial summary judgment. It chose to proceed anyway. The resulting judgment is not bad luck or hindsight criticism. It is the direct and foreseeable cost of a deliberate decision to withhold a public record in violation of Ohio law.

Petticord’s Role and the Cost of Withholding

The record in the Barilla mandamus action establishes that Dan Petticord, serving at the time as Chief of the Civil Division of the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office, was not a peripheral figure in this dispute but a central participant. Testimony and exhibits admitted at the evidentiary hearing show that Petticord was aware of the existence of the draft EEOC complaint, aware that a formal public-records request had been made for it, and involved in communications concerning that document and related settlement discussions with outside counsel. This was not a situation where a record was lost, overlooked, or misunderstood. The evidence shows contemporaneous knowledge and deliberate decision-making at the highest civil level of the Prosecutor’s Office.

The court record further reflects that Petticord testified regarding emails and draft settlement agreements exchanged with counsel for the parties, including discussions tied to a potential hostile work environment claim and the first settlement agreement that was ultimately signed. The court rejected the County’s attempt to characterize the draft EEOC complaint as something other than a public record, explicitly finding that the document was subject to disclosure under Ohio law. That rejection is critical. It means the court did not accept the premise that withholding the record was reasonable, cautious, or legally justified. The court found the opposite. The County’s position failed under straightforward application of the Public Records Act.

Once a public office knows a record exists, knows it is responsive to a request, and knows that its status as a public record is at least reasonably clear, the legal risk of noncompliance is no longer abstract. It becomes calculable.

This is the point at which the narrative shifts from a single adverse ruling to a demonstrable pattern of risk creation through deliberate withholding. Once a public office knows a record exists, knows it is responsive to a request, and knows that its status as a public record is at least reasonably clear, the legal risk of noncompliance is no longer abstract. It becomes calculable. Ohio Revised Code 149.43(C) fixes statutory damages on a per-day basis once a mandamus action is filed, and it authorizes courts to award reasonable attorney fees when a requester is forced to litigate to obtain records that should have been produced voluntarily. Every additional day of noncompliance increases exposure. Every hour spent defending a position that does not survive judicial scrutiny increases the fee award the public will ultimately pay.

Despite that reality, the County still chose to fight. Even after partial summary judgment was entered finding the record was improperly withheld, the County continued litigating instead of complying and mitigating damage. That decision cannot be explained as caution or uncertainty. At that stage, it was defiance of a judicial determination, and the consequences that followed were not accidental. They were the predictable result of refusing to accept the legal boundary the court had already drawn.

Critically, this decision did not occur in a vacuum. The withheld document was not a routine administrative record. It implicated a settlement involving J.D. Tomlinson and Battistelli, a settlement whose legality, approval process, and surrounding conduct have already raised serious questions in other proceedings and public reporting. Transparency carried risk for the County, but that risk was political and reputational, not legal. The legal risk came from choosing concealment over compliance. The refusal to produce the record did not shield the County from scrutiny. It intensified it, converted internal discomfort into public liability, and culminated in a judgment that now stands as a permanent part of the County’s record.

In short, the cost imposed by the Barilla judgment was not the cost of transparency. It was the cost of resisting it after the law, the statute, and the court had all made the obligation unmistakably clear.

Public Records Law Is Not Optional Governance

Ohio’s Public Records Act is written to be intentionally unforgiving, and that design is not accidental. Revised Code 149.43(C) exists precisely because experience has shown that public offices frequently do not comply with disclosure obligations voluntarily. The General Assembly resolved that problem by removing discretion from the equation. The statute flips the incentive structure in unmistakable terms. If a public office complies with the law, there is no lawsuit, no fee award, and no damages. If it refuses, delays, or withholds a record it is legally required to produce, and the requester is right, the public office pays. There is no middle ground built into the statute and no safe harbor for strategic noncompliance.

The Barilla judgment reinforces a principle that now appears repeatedly across Lorain County litigation and public-records disputes. Delay is not neutral. Withholding is not cost-free. Obstruction does not preserve leverage. It multiplies liability. Every day a record is withheld after a mandamus action is filed increases statutory exposure. Every motion filed to defend an untenable position increases attorney-fee exposure. What may begin as an attempt to control information predictably ends as a transfer of public funds to cover the cost of resisting transparency.

This outcome is not the product of hindsight or evolving legal standards. It is the direct application of settled law. Ohio courts have repeatedly held that the Public Records Act must be construed liberally in favor of disclosure and strictly against the public office that withholds records. The statute is clear, the remedies are explicit, and the consequences are well known. County prosecutors, county commissioners, and law directors are presumed to know this framework because it governs their daily work. They are not permitted to treat compliance as a matter of judgment, convenience, or political calculation.

The lesson of the Barilla case is therefore not subtle.

The lesson of the Barilla case is therefore not subtle. Public-records law is not a policy preference. It is not guidance. It is not aspirational. It is mandatory governance backed by financial consequences that attach the moment a public office chooses concealment over compliance. The judgment simply enforced what the law has said all along.

See the Case File Here: https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:va6c2:ba11861b-ecfc-4a48-b2ed-ac1c36caf578

The Barilla Loss in Context of Broader Fiscal Exposure

Standing alone, a judgment in the range of thirty-three thousand dollars can be brushed aside as routine litigation expense, the kind of cost public entities expect to absorb over time. That framing collapses, however, once the Barilla loss is placed in its actual fiscal context. This judgment did not arise in isolation. It landed on top of a series of major financial decisions that have already exposed Lorain County to extraordinary and compounding risk, much of it self-inflicted and much of it still ongoing.

The Midway Mall acquisition is the clearest starting point. Approximately $13.9 million in public funds were committed to a declining enclosed mall at a time when retail vacancy, structural obsolescence, and market contraction were well documented. That money was not merely spent. It was locked into an asset that generated continuing operational losses. By the County’s own figures, those losses approached roughly $750,000 per year, year after year, while the principal remained tied up and unavailable for other public needs. The opportunity cost alone, including lost interest and foregone investment in core services, represents a permanent drain on County finances that cannot be recovered by optimism or post-hoc justification.

Layered on top of that exposure is the County’s approximately $20 million commitment to the MARCS radio system. Whatever the merits of the system itself, the transition has not been clean, uncontested, or insulated from legal risk. Ongoing litigation, including the Cleveland Communications case, means the County is still spending public funds on legal defense, consultants, and internal resources to sustain decisions that continue to be challenged. These are not speculative costs. They are real expenditures occurring now, with the added risk of adverse judgments or settlements still unresolved.

Against that backdrop, repeated public-records losses take on a different character. The Barilla judgment is not an outlier or an unfortunate fluke. It is the predictable product of a governance approach that treats transparency as a threat to be managed rather than a legal duty to be fulfilled. Each time the County chooses to withhold records, delay compliance, or litigate disclosure obligations that are clearly defined by statute, it adds another layer of unnecessary financial exposure. Attorney-fee awards, statutory damages, and court costs are not incidental. They are the built-in consequences of choosing concealment over compliance.

When these elements are viewed together, the problem is no longer a single bad decision or an isolated misjudgment. It is a pattern. Public money is committed to high-risk projects without adequate safeguards. When scrutiny follows, records are withheld. When withholding triggers litigation, the County fights rather than complies. When the County loses, it pays with public funds. The cycle then repeats. Governance by concealment leads to litigation, and litigation leads to payment, all while the underlying financial exposures remain unresolved.

The Barilla loss fits squarely within that pattern. It did not create the County’s fiscal vulnerability. It revealed it.

Accountability Does Not Expire With Office

One of the most enduring and corrosive myths in local government is the idea that accountability ends when a term of office ends. It does not. Authority may rotate, titles may change, and election cycles may reset the seating chart, but responsibility does not evaporate with the calendar. Paper trails do not dissolve. Emails do not lose relevance. Decisions do not become untethered from their origins simply because an oath was taken at a later date or a different title was assumed. Public accountability is anchored to conduct, not to the convenient boundaries of electoral timelines.

When the record shows that decisions were initiated, encouraged, coordinated, or shaped before an individual formally took office, that history remains fully relevant to evaluating their role in what followed. There is no legal doctrine that insulates someone from scrutiny because they were “not yet sworn in” when groundwork was laid. Participation does not require authorship. Being present, signaling approval, facilitating continuity, or declining to object when objection is warranted all carry weight. Ohio law does not recognize a defense based on passive concurrence. Ignorance of the law is not a defense. Silence in the face of known risk is not neutrality. There is no such thing as rubber-stamp immunity in public office.

This principle is especially important in contexts where appointments to bodies such as port authorities, boards, or advisory entities precede elections and later translate seamlessly into policy continuity once those individuals assume elected office. When the same actors appear before and after an election advancing the same objectives, approving the same strategies, or benefiting from the same arrangements, the dividing line of Election Day becomes legally and ethically irrelevant. The public does not experience governance in fragments. It experiences outcomes. Accountability therefore follows the continuity of conduct, not the convenience of officeholding dates.

To suggest otherwise is to invite a system where responsibility is endlessly deferred, where decisions are made in advance and ratified later, and where no one is ever answerable because each step can be attributed to a different moment in time. That is not how public trust is preserved, and it is not how Ohio law understands accountability. When public money is committed, when risks are assumed, and when transparency is resisted, responsibility attaches to the people who participated in that process, regardless of when their name first appeared on the ballot.

The Ethics Gap and Prosecutorial Discretion

There is a structural problem in Ohio’s accountability framework that is too often ignored because acknowledging it is uncomfortable. It deserves sober analysis rather than rhetorical dismissal, because it goes directly to how misconduct can persist without formal adjudication even when documentary evidence exists.

The Ohio Ethics Commission has no arrest power and no independent authority to bring criminal charges. Its role is investigative and referential. When the Commission identifies potential violations of ethics law, it refers those matters to the appropriate prosecuting authority. From that point forward, the fate of the referral rests entirely with the prosecutor. If the prosecutor acts, the matter proceeds. If the prosecutor declines, delays indefinitely, or chooses not to pursue charges, the case effectively dies on the vine. There is no mandatory explanation required. There is no external override. There is no public accounting obligation built into that decision.

That structural reality does not, by itself, prove wrongdoing. It does, however, create a significant risk point in the accountability chain, one that becomes impossible to ignore when the same individuals and institutions appear repeatedly across settlements, approvals, refusals to disclose records, and decisions not to prosecute. When ethics referrals, public-records disputes, and settlement negotiations intersect around the same actors, prosecutorial discretion stops being an abstract concept and becomes a material factor in whether accountability is realized or quietly extinguished.

The Barilla record illustrates how fragile public accountability becomes when transparency is resisted and discretion is exercised without explanation. The refusal to disclose records delayed public scrutiny. The continued litigation multiplied public cost. The eventual disclosure came only after a court order and a fee award. That same dynamic applies, with even higher stakes, when ethics matters are involved. Without transparency, the public cannot evaluate whether discretion was exercised prudently, politically, or protectively. Without records, there is no way to distinguish between a reasoned declination and a quiet burial.

This is where public trust erodes. Not because discretion exists, but because it operates behind closed doors while the financial and ethical consequences are borne by the public. Prosecutorial discretion is a necessary feature of the justice system, but it is not meant to function as an invisibility cloak. When discretion is combined with secrecy, withheld records, and recurring involvement by the same officials, accountability does not merely weaken. It collapses.

The lesson from Barilla is not limited to public-records law. It is broader and more troubling. When transparency is resisted at the records level and discretion is unexamined at the prosecutorial level, the mechanisms designed to check misconduct fail in tandem. What remains is a system where outcomes are controlled not by law, but by who decides what the public is allowed to see and which referrals are allowed to move forward.

What Was Lost and What Has Now Been Set

The most damaging losses in this record are not confined to a single judgment entry or a line item on a budget spreadsheet. They include consequences that will compound quietly over time, long after the headlines fade. Every dollar spent defending avoidable litigation is a dollar that cannot be spent on deputies, first responders, senior services, infrastructure maintenance, or rate stabilization. Those foregone investments do not reappear when a case closes. They simply vanish from the list of things government could have done but chose not to prioritize.

By expressly finding that $350.00 per hour constituted a reasonable market rate for public-records mandamus litigation in Lorain County, the court did not just resolve one fee dispute. It set a benchmark.

The Barilla judgment adds another, more consequential layer to that loss. By expressly finding that $350.00 per hour constituted a reasonable market rate for public-records mandamus litigation in Lorain County, the court did not just resolve one fee dispute. It set a benchmark. That finding now exists as part of the public judicial record, and it will be cited. Attorneys handling public-records cases against Lorain County, the City of Lorain, and other county agencies can now point to a court-approved rate and argue, with support, that this is the going rate for competent representation in these matters. Courts do not evaluate fee requests in a vacuum. They look to prior findings. Barilla has now supplied one.

That means the cost of future noncompliance has effectively increased. Every ongoing and future public-records case carries with it the real possibility of attorney-fee awards calculated at that same hourly rate, multiplied by however many hours the public office forces counsel to expend by refusing to comply promptly. What may once have been dismissed as “manageable exposure” is now measurably more expensive, precisely because the County chose to litigate rather than comply and lost.

Against that backdrop, the broader financial harm becomes impossible to ignore. Forty million dollars, whether aggregated through speculative investments, recurring operational losses, unnecessary litigation, lost interest, or now escalating fee exposure, is not abstract. It is material harm to residents who never consented to have their tax dollars used as leverage in secrecy-driven decision making. It represents patrol hours not funded, equipment not purchased, programs not expanded, and rates not stabilized. It represents opportunity permanently surrendered.

The true loss, then, is not just what the County has already paid. It is what it has normalized. By choosing concealment over compliance, litigation over transparency, and discretion without explanation, the County has made future accountability more expensive by design. That cost will not appear all at once. It will surface incrementally, case by case, judgment by judgment, until the cumulative effect becomes undeniable.

Those losses will never be fully counted. But they will be felt.

When the Government Admits the Risk and Chooses Delay Anyway

There is an additional fact that makes the Barilla outcome even more damning, and it strips away any remaining claim that these losses were unforeseen or unavoidable. Inside Lorain government buildings, the City itself has posted signage summarizing Ohio public-records law. That signage explicitly acknowledges that unreasonable delay or denial of public records can result in litigation and that, if the requester prevails, the public office will be required to pay reasonable attorney fees.

This is not buried legal advice or obscure statutory language. It is an affirmative acknowledgment by the City, displayed on its own walls, that delay equals lawsuits and lawsuits equal financial liability. In other words, the risk has been formally recognized, internalized, and communicated by the government itself.

That matters.

When a public office has posted notice that noncompliance with Ohio Revised Code 149.43 can and will result in attorney-fee awards, it cannot later plausibly argue surprise when exactly that outcome occurs. The Barilla judgment did not introduce a new rule. It enforced the very consequence the City already warns about in its own facilities. The law was not hidden. The remedy was not obscure. The exposure was openly acknowledged.

This transforms the narrative from one of alleged misunderstanding into one of conscious choice. When delay persists despite written requests, narrowing, cure attempts, in-person inspection demands, and now posted acknowledgment of liability, the conclusion is unavoidable. The public office is not operating under confusion. It is operating under calculation.

That calculation appears repeatedly in the record. Delay is treated as leverage. Withholding is treated as strategy. Compliance is deferred until a court intervenes. The posted signage proves that officials understand the consequences of that approach. They simply chose to proceed anyway, shifting the cost of that decision onto taxpayers once litigation became unavoidable.

In this context, Barilla is not merely a loss. It is the predictable execution of a risk the City and County already knew existed and publicly warned about. The judgment confirms that courts will not excuse delay simply because it was intentional, bureaucratic, or lawyer-driven. Knowledge of the law does not mitigate liability under the Public Records Act. It aggravates it.

For those currently litigating public-records access against the City of Lorain, this admission matters going forward. It reinforces arguments of bad faith, unreasonable delay, and willful noncompliance. It undermines claims that denials were procedural or inadvertent. When the government posts a warning that delay leads to lawsuits and attorney fees, then proceeds to delay anyway, the resulting liability is not accidental. It is self-inflicted.

Barilla proves the warning was real. The posted sign proves the warning was known. Together, they eliminate any remaining fiction that these outcomes are the cost of doing business. They are the cost of ignoring a law the City itself tells the public it understands.

That is not misinterpretation. That is documented awareness followed by documented refusal. And once that sequence is established, accountability is no longer a matter of opinion. It is a matter of record.

Final Observation

Why Barilla Is Not an Isolated Loss and Why It Matters to Every Ongoing Records Fight in Lorain

The Barilla case is not about one requester, one document, or one moment where a public office made a bad call and paid for it. It is a case study in how a governing culture behaves when it assumes that compliance is optional, delay is consequence free, and accountability can be managed rather than honored. That culture is now documented, adjudicated, and priced by a court of law.

For those of us who have spent months, and in some cases years, fighting for basic public-records access in Lorain County and the City of Lorain, Barilla reads less like a surprise and more like confirmation. It confirms what repeated experience has already shown. When a public office decides that it will not produce records unless forced, the dispute does not resolve quietly. It escalates. It hardens. It becomes litigation. And once it becomes litigation, the public office is no longer controlling cost or outcome. The statute is.

The court in Barilla corrected a false assumption that has clearly taken root in local government practice. That assumption is that the worst consequence of withholding records is irritation, criticism, or a demand letter that eventually goes away. The court made clear that the real consequence is financial, structural, and permanent. The bill is now public. The judgment is final. The record cannot be rewritten, explained away, or buried in internal talking points.

What makes this especially significant is that Barilla does not stand alone. It now exists alongside ongoing and active public-records litigation against the City of Lorain and other county agencies, including cases where the same patterns are present. Prolonged delay. Repeated refusals to permit inspection. Failure to identify custodians. Failure to cite statutory exemptions. Blanket privilege assertions untethered from record-specific analysis. Attorney-driven denials after months of notice and narrowing. These are not hypotheticals. They are documented practices already laid out in verified complaints, cure requests, motions for expedited inspection, and proposed contempt frameworks that are now part of the public court record.

The significance of Barilla is not just that the County lost. It is that the court validated the economic reality of public-records enforcement. By expressly finding that $350 per hour is a reasonable market rate for public-records litigation in Lorain County, the court did more than resolve a fee dispute. It reset the cost structure for noncompliance going forward. Every public office that now chooses delay over disclosure does so knowing that the meter runs at a court-approved rate, and that the statute places that cost squarely on the government, not the requester.

For those currently litigating records access against the City of Lorain, that matters. It means future courts will not be evaluating fee requests in a vacuum. They will be looking at Barilla as proof of market reasonableness. It means arguments that fees are excessive, inflated, or opportunistic have already been weakened by a judicial finding entered after an evidentiary hearing. It means that every additional hour spent resisting inspection, every unnecessary motion, every attorney-issued denial after notice, carries a quantifiable and escalating public cost.

This is where the real loss lies, and why it cannot be captured by a single number. The most damaging losses are not always reflected neatly on a balance sheet. They appear as opportunity cost. Every dollar spent defending avoidable litigation is a dollar not spent on deputies, firefighters, EMS staffing, senior services, infrastructure repair, or rate stabilization. Forty million dollars, whether aggregated through speculative investments, recurring operational losses, unnecessary litigation, lost interest, or now escalating attorney-fee exposure, is not abstract. It is material harm imposed on residents who never consented to have their money used to subsidize secrecy-driven decision making.

Barilla also exposes a deeper institutional failure. Public accountability does not collapse all at once. It erodes through small, repeated choices. A delay justified internally as caution. A denial framed as process. A privilege claim asserted reflexively. A refusal to permit inspection because review is not yet complete. Each choice pushes accountability one step further away from the public and one step closer to the courthouse. By the time a judge enters judgment, the damage is already done. The money is already spent. The trust is already depleted.

Everything that follows from here will rise or fall on documents, emails, and sworn testimony, not on rhetoric, spin, or after-the-fact explanations. That is exactly where these stories belong. Public-records law exists to ensure that governance is evaluated on evidence, not assurances. Courts exist to enforce that promise when public offices refuse to honor it voluntarily.

And yes, this is one man’s opinion. But it is an opinion grounded in judgments, statutes, verified pleadings, and records that no longer belong to the County or the City to hide. The Barilla decision did not create these problems. It exposed them, priced them, and put them on the record. What happens next will depend entirely on whether Lorain’s public offices finally accept that transparency is not optional governance, or whether they continue to learn that lesson one judgment at a time.

Legal Disclosure and Editorial Notice

This article is an investigative analysis and commentary based on publicly available court records, filed pleadings, statutory law, sworn testimony, and judicial findings. It reflects the author’s interpretation of those materials and is published for informational and journalistic purposes only.

Nothing contained herein constitutes legal advice, creates an attorney client relationship, or should be relied upon as a substitute for consultation with qualified legal counsel. All legal conclusions discussed are derived from publicly entered judgments, statutes, and procedural records as of the date of publication and may evolve as additional filings, appeals, or related litigation proceed.

All matters referenced involve public officials, public offices, and issues of public concern. Allegations remain allegations unless and until adjudicated by a court of competent jurisdiction. Findings attributed to courts are quoted or paraphrased from official judgment entries and hearing records.

This publication is protected expression under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution. The work reflects the author’s opinions, analysis, and reporting, grounded in documentary evidence and the public record.

Images, illustrations, or visual elements accompanying this article may include AI assisted or AI generated graphics used for illustrative purposes only and not as factual representations of real persons or events unless expressly stated.

© 2026 Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction without permission is prohibited.

Does Lorain’s government really believe in transparency or is that public records Notice published on the wall of Lorain City Hall merely a Deception?

Why must citizens in Lorain being refused for months public records?

What is being hidden? Why?