City of Lorain Authorizes Public Funds to Defend Individual Defendants in Federal Civil Rights Case

Documents show executives coordinated investigations while taxpayers funded personal legal defenses.

The City of Lorain has authorized the use of public funds to retain private legal counsel for Police Chief James McCann and Assistant Law Director Joseph LaVeck in the federal civil rights lawsuit Knapp v. City of Lorain, et al., pending in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. Both McCann and LaVeck are sued strictly in their individual capacities and face personal civil liability exposure under multiple counts of the verified complaint, including claims brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 1983 and Ohio Revised Code 2307.60. The operative pleadings further seek punitive damages against individual defendants based on allegations of intentional, willful, and retaliatory conduct, as well as civil liability arising from alleged criminal acts.

This authorization was issued while Mayor Jack Bradley and Safety Service Director Rey Carrion also remain named individual defendants in the same action, facing personal liability exposure arising from the same nucleus of factual allegations. The approval and funding of private legal defense for McCann and LaVeck were processed through City administrative authorization and paid through contractual services accounts controlled by the same executive branch officials who are named as defendants in the litigation. As a result, City officials with direct personal exposure in the pending lawsuit participated in or remained embedded within the authorization structure for the expenditure of public funds used to defend individual defendants from personal liability.

These funding approvals do not exist in isolation. They now coexist with a documented record of executive level coordination involving the selection and handling of an administrative investigation concerning Chief McCann, the transmission of complaint materials to the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office and Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office for review, and direct mayoral participation in investigative decision making related to the same subject matter forming the basis of the pending federal claims. Internal correspondence confirms that Safety Service Director Carrion coordinated review of the complaint with the Sheriff’s Office, that a complete compilation of complaints was forwarded to the Prosecutor for evaluation, and that Mayor Bradley subsequently requested access to that investigatory material. Separate City correspondence further confirms that Mayor Bradley directly participated in determining who would conduct the administrative investigation and expressed his availability to respond to investigative questioning.

At the time these investigative coordination actions occurred, Mayor Bradley, Safety Service Director Carrion, and Police Chief McCann each had an active or foreseeable personal legal exposure arising from the same underlying factual matters. Those same matters now form the basis of the personal liability claims pending in federal court.

The City’s later decision to fund individual defense counsel for McCann and LaVeck occurred against this documented backdrop of executive involvement in investigation selection, prosecutorial review coordination, and internal handling of allegations that subsequently became the subject of individual capacity civil rights litigation.

The totality of this record establishes that the authorization of public funds for private defense counsel in this matter was not undertaken in a vacuum. It occurred contemporaneously with documented executive branch involvement in investigation management, prosecutorial coordination, and internal complaint handling, all while multiple participants in those processes remained named individual defendants in the litigation. These facts present an objective intersection between investigative control, prosecutorial review coordination, and financial authorization for personal legal defense that properly falls within the scope of legislative, ethics, and judicial inquiry.

Status of the Federal Lawsuit and Individual Capacity Claims

The operative verified complaint in Knapp v. City of Lorain, et al., pending in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, names James McCann, Rey Carrion, Jack Bradley, Joseph LaVeck, and Tim Weitzel strictly as individual capacity defendants. Each defendant is alleged to have acted under color of law while engaging in conduct asserted to fall outside the protections of lawful, good faith governmental activity.

The causes of action pled include First Amendment retaliation under 42 U.S.C. 1983, destruction or concealment of public records in violation of Ohio Revised Code 149.351, and civil liability for injuries caused by criminal acts pursuant to Ohio Revised Code 2307.60, along with related state law claims such as tortious interference with contract and intentional infliction of emotional distress. The complaint alleges that the acts at issue were intentional, willful, retaliatory, concealed, and carried out with knowledge of their unlawful nature.

Punitive damages are sought against multiple individual defendants based upon allegations of malicious, oppressive, and reckless conduct. These punitive claims are directed exclusively at the individual defendants and not the municipal corporation.

The pleaded facts arise from a multi year sequence of public records disputes governed by Ohio Revised Code 149.43, administrative complaints and licensing board communications involving the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage and Family Therapist Board, and a series of alleged retaliatory actions following civic advocacy, protected speech, and investigative reporting. The pleadings assert that adverse governmental actions followed those protected activities and were carried out through coordinated administrative, law enforcement, and legal channels.

Use of Public Funds for Personal Legal Defense

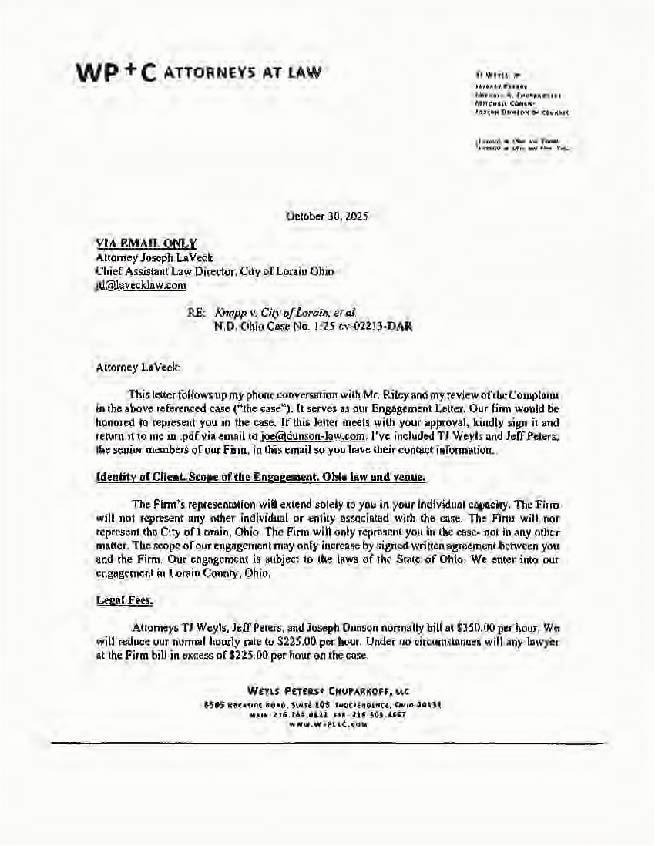

Despite the strictly individual-capacity posture of the claims asserted in Knapp v. City of Lorain, et al., the City of Lorain authorized the use of public funds to retain private legal counsel for former Police Chief James McCann and Assistant Law Director Joseph LaVeck for their personal defense in the pending federal civil rights litigation.

Both McCann and LaVeck are sued individually and face direct personal civil liability exposure under federal and Ohio law. The defense approvals were processed through City administrative authorization and funded through contractual services accounts of the same municipal government that remains a named defendant in the case.

At the time these defense authorizations were issued, Mayor Jack Bradley and Safety Service Director Rey Carrion were themselves named individual defendants in the same federal action and remained embedded within the executive and administrative structure through which the defense funding approvals were processed. As a result, City officials with direct personal exposure in the litigation participated in or remained situated within the authorization chain approving the expenditure of public funds to defend co-defendants from individual liability.

The operative effect of this authorization is straightforward and undisputed. Taxpayer funds are being used to pay for the private legal defense of individual defendants sued for personal misconduct, while the same executive branch structure that authorized those expenditures remains populated by officials who themselves face individual civil liability arising from the same nucleus of factual allegations.

These defense funding approvals exist independently of any adjudication on the merits. They do not arise from a judicial finding of statutory entitlement, a court-ordered indemnification ruling, or a completed immunity determination. They are administrative spending decisions undertaken in real time, within an active litigation environment in which multiple approving officials remain direct participants as individual defendants.

For purposes of the public record, the relevant facts are narrow but significant. The City is paying for personal legal defense. The beneficiaries of that funding are sued in their individual capacities. The authorization structure includes officials who themselves face individual exposure in the same case. The defense expenditures therefore sit at the direct intersection of public finance authority and private civil liability.

At present, no publicly released City record reflects the appointment of independent special counsel for neutral review of these indemnification and conflict issues, no designation of a special prosecutor to independently evaluate potential criminal exposure, no initiation of an independent ethics investigation, and no authorization of funding for an outside investigative review. The only documented defense related expenditure thus far concerns the personal legal defense of individual defendants sued for retaliatory and criminally alleged conduct.

Under Ohio fiduciary law, municipal officers act as trustees of public funds and are prohibited from authorizing expenditures for private benefit absent clear statutory authority. Where individual defendants with direct personal liability exposure participate in or remain embedded within the authorization structure approving public expenditures for personal legal defense, those approvals become subject to legislative scrutiny, ethics review, and judicial oversight for compliance with Ohio statutory and common law limitations on public spending.

Executive Coordination With Sheriff and Prosecutor Regarding Knapp Complaints

Internal City records titled Re: Aaron Knapp Conflict document direct executive-level coordination between Mayor Jack Bradley, Safety Service Director Rey Carrion, the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office, and the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office concerning complaints submitted by Aaron Knapp regarding Chief James McCann.

Those records establish that Safety Service Director Carrion communicated directly with Major Richard Bosley of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office regarding review of the complaints. Following that exchange, Captain Robert Vansant of the Sheriff’s Office transmitted a thumb drive containing the full compilation of Knapp’s complaints to the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office for prosecutorial review. After that transfer occurred, Mayor Bradley requested access to the same investigative materials.

This communication chain places the City’s top executive officers inside the external law-enforcement and prosecutorial review process for complaints that later became part of the factual basis of the federal civil rights litigation now pending in the Northern District of Ohio.

At the time of this coordination, Mayor Bradley and Safety Service Director Carrion were already connected to the subject matter of the complaints through internal records handling, administrative oversight, and direct executive supervision of Chief McCann. Those same officials are now sued in their individual capacities based on the same core factual events.

This contemporaneous overlap between executive investigative coordination and later personal civil liability establishes that the complaint handling process, the external prosecutorial routing, and the present litigation are not separate institutional events. They are sequential phases of a continuous executive-controlled response to the same underlying allegations.

This coordination record therefore forms part of the structural backdrop against which later defense funding decisions were authorized.

Mayoral Involvement in the McCann Administrative Investigation

Separate internal City correspondence titled Re: Administrative Investigation re: A. Knapp documents direct involvement by Mayor Jack Bradley in the initiation and procedural handling of the internal administrative investigation concerning Police Chief James McCann.

That correspondence establishes that Mayor Bradley was not merely notified of the investigation but actively participated in directing how it would be conducted. The Mayor instructed that Lori Kokoski be engaged to perform the administrative investigation and further stated that he would remain available to answer questions arising during the investigative process.

This written exchange places the Mayor inside the investigative chain itself as an active participant in investigator selection and investigative response availability rather than as a detached supervisory official.

At the time this investigative participation occurred, Mayor Bradley was already connected to the subject matter of the allegations through public records disputes, executive oversight of the Police Department, and internal complaint routing involving the same underlying conduct attributed to Chief McCann.

The investigation therefore did not occur at arm’s length from the executive branch. It unfolded under direct mayoral procedural involvement before the filing of the federal civil rights action that now names the Mayor as an individual defendant based on overlapping factual allegations.

This record establishes that executive investigatory control preceded the current litigation and forms part of the continuous administrative response to the same core dispute that now exists in federal court.

McCann’s Personal Control Over Public Records in Direct Conflict With Ohio Supreme Court Precedent

On June 13, 2023, then Chief of Police James McCann issued a written communication asserting that communications between himself and the Lorain Law Department were protected by attorney client privilege and therefore not subject to disclosure under the Ohio Public Records Act. In that same communication, he simultaneously asserted that no responsive records existed while acknowledging that at least one responsive email had been forwarded internally and would later be provided in PDF format.

On June 20, 2023, the Lorain Police Department formally denied access to requested body camera and lobby video recordings, citing the existence of an ongoing administrative investigation and asserting that the materials constituted confidential law enforcement investigatory records under Ohio Revised Code 149.43(A)(1)(h).

On June 21, 2023, Chief McCann issued a written directive asserting that during the pendency of any active criminal or administrative investigation, video evidence was categorically not a public record until the investigation was completed. In that same written directive, McCann further ordered that employees of the Lorain Police Department were no longer to respond to any public records requests submitted by Aaron Knapp and that all such requests were to be forwarded exclusively to Captain A. J. Mathewson and to McCann himself for disposition.

Through that directive, Chief McCann personally centralized all decision making authority over public records acknowledgments, denials, investigative exemptions, and disclosure timing within his own office.

These directives directly conflict with controlling Ohio Supreme Court precedent governing the Ohio Public Records Act.

In State ex rel. Cincinnati Enquirer v. Hamilton County, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that whether a document is a public record is determined by the content and function of the record, not by the identity of the custodian or the subjective purpose asserted by a public office.

In State ex rel. Beacon Journal Publishing Co. v. City of Akron, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that public offices may not withhold records simply because they are connected to an investigation unless the statutory elements of the investigatory exemption are strictly satisfied.

In State ex rel. Ohio Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association v. Mentor, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that investigatory exemptions must be strictly construed and that a public office bears the burden of proving that each statutory element applies to each specific withheld record.

In State ex rel. Glasgow v. Jones and State ex rel. Ware v. Kurt, the Supreme Court of Ohio reaffirmed that the Public Records Act is to be construed liberally in favor of access and that exemptions are to be narrowly applied.

Ohio Revised Code 149.43 further provides that body worn camera recordings and security video are subject to statutory disclosure analysis and enumerated exemptions, and that requesters possess express statutory rights to seek relief through mandamus or the Ohio Court of Claims when access is denied.

Chief McCann’s categorical declaration that video evidence is not a public record during any active investigation is directly contrary to both the statutory text and multiple controlling holdings of the Supreme Court of Ohio.

At the time these written directives were issued, the City of Lorain had not initiated any special counsel review, independent prosecutorial conflict evaluation, or ethics investigation concerning the handling of public records arising from these disputes. All decision making authority remained consolidated within the same executive structure that was the subject of the records disputes themselves.

These written actions by Chief McCann establishing personal control over public records determinations form part of the factual basis of the later federal civil rights claims and establish a continuous chain of personal decision making authority over records access that existed before litigation was initiated.

Findings of Fact Regarding Ohio Supreme Court Public Records Precedent

The following Ohio Supreme Court decisions constitute controlling authority governing the public records conduct described in this case:

In State ex rel. Cincinnati Enquirer v. Hamilton County, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that whether a document is a public record is determined by its content and function, not by the identity of the custodian or a unilateral designation by a public office.

In State ex rel. Beacon Journal Publishing Co. v. City of Akron, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that public offices may not withhold records simply because they are connected to an investigation unless the specific statutory elements of the investigatory exemption are strictly met.

In State ex rel. Ohio Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association v. Mentor, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that investigatory records exemptions must be strictly construed and that a public office bears the burden of proving that each element of the exemption applies to each withheld record.

In State ex rel. Glasgow v. Jones, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that a public office may not deny access to records by routing communications through counsel or by asserting privilege where the content and function of the record serve a public purpose.

In State ex rel. Ware v. Kurt, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that the Public Records Act is to be construed liberally in favor of access and that exemptions must be narrowly applied.

Together, these cases establish that investigative status alone does not extinguish public records status, that privilege claims cannot be used to reclassify otherwise public records, and that unilateral control by a chief executive or law enforcement official cannot override statutory disclosure duties imposed by Ohio Revised Code 149.43 and 149.01.

Taxpayer Standing and Public Funds Enforcement Under Ohio Law

Under Ohio law, municipal officers act as trustees of public funds and owe a fiduciary duty to the taxpayers of the political subdivision. Public officials are prohibited from authorizing the expenditure of public funds for private benefit absent clear statutory authority.

Ohio Revised Code 733.56 authorizes any taxpayer of a municipal corporation to bring an action in the name of the municipality to restrain the misapplication of funds or the abuse of corporate powers. This statute provides a direct mechanism for taxpayers to challenge the unlawful expenditure of public money.

Ohio courts have consistently held that when public funds are expended in violation of statute or for an ultra vires purpose, taxpayers possess standing to seek injunctive relief, restitution, and judicial review of the expenditure.

Ohio Revised Code 2744.07 permits defense and indemnification of public employees only when the employee acted within the scope of employment and without malicious purpose, in bad faith, or in a wanton or reckless manner. Where pleadings allege intentional, retaliatory, malicious, or criminal conduct, the legal availability of public defense funding is placed into dispute at the outset of the litigation.

When public funds are advanced to defend individual defendants accused of conduct that may legally bar indemnification, and when officials with direct personal liability exposure participate in or remain embedded within the authorization structure for those expenditures, taxpayer standing is triggered for judicial review of the legality of the expenditure.

Under these statutes and controlling precedent, expenditures of public funds for personal legal defense in circumstances involving alleged bad faith, malicious conduct, or criminally rooted acts fall within the proper scope of taxpayer enforcement actions, legislative inquiry, and judicial oversight.

The Rosenbaum Representation and the Structural Collapse of the Indemnification Firewall

The City of Lorain selected and authorized the use of public funds to retain attorney Jonathan E. Rosenbaum as private defense counsel for former Police Chief James McCann in his individual capacity in the federal civil rights action Knapp v. City of Lorain, et al., pending in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. McCann is sued personally under 42 U.S.C. 1983, Ohio Revised Code 149.351, and Ohio Revised Code 2307.60, with punitive damages expressly pled based upon allegations of intentional retaliation, public records obstruction, and civil liability arising from criminal acts.

Rosenbaum’s selection carries unique and legally consequential historical weight within Lorain County. For nearly two decades, Rosenbaum served as a senior assistant prosecutor in the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office and was one of the lead prosecutors in the 1994 Head Start prosecutions that resulted in the convictions of Nancy Smith and Joseph Allen. Those convictions were later overturned, and the case is now recognized as one of the most severe wrongful conviction scandals in county history. At the original trials, Jack Bradley, now Mayor of the City of Lorain and a current individual defendant in this federal action, served as defense counsel for Nancy Smith. That adversarial relationship arising from prosecutorial power and executive protection is an undisputed matter of public record.

Following his departure from the Prosecutor’s Office, Rosenbaum entered private civil practice and remains deeply embedded in public records enforcement litigation against government actors. Most notably, Rosenbaum presently represents James Barilla in a high profile Ohio Public Records Act enforcement action against Lorain County Prosecutor J.D. Tomlinson and County officials arising under Ohio Revised Code 149.43. In that litigation, Rosenbaum has affirmatively advanced the statutory obligations of public offices to release records, challenged claims of investigatory exemption, and litigated against unlawful concealment, delay, and obstruction of public records by government officials.

In direct contrast, Rosenbaum now defends former Chief McCann in a civil rights case in which McCann is accused of personally centralizing records authority, asserting unilateral privilege to block disclosure, coordinating prosecutorial routing of records disputes, delaying and denying the release of video and email records, and engaging in conduct that directly implicates Ohio Revised Code 149.43 and Ohio Revised Code 149.351. The same attorney who presently prosecutes transparency enforcement against the County is now publicly funded to defend a former police chief accused of committing that very obstruction.

This reversal of doctrinal posture does not occur in isolation. It unfolds within the same county governance structure, the same executive network, and the same political ecosystem. Mayor Bradley remains a named individual defendant in this federal case. Safety Service Director Rey Carrion remains a named individual defendant. The City of Lorain itself remains a Monell defendant. Rosenbaum therefore occupies a position where he simultaneously litigates for transparency enforcement on behalf of citizens while receiving taxpayer funds to defend alleged transparency violations by an executive actor within the same governmental sphere.

That structural contradiction directly intersects with the statutory limits of Ohio Revised Code 2744.07. Public defense funding is permitted only where the employee acted in good faith, within the scope of employment, and without malicious purpose, bad faith, wanton misconduct, or criminal conduct. The federal complaint pleads precisely the disqualifying mental states. It further asserts personal civil liability under Ohio Revised Code 149.351 for records concealment and Ohio Revised Code 2307.60 for injuries arising from criminal acts. Those statutes impose personal liability independent of employment status and independent of municipal absorption.

By authorizing taxpayer funds to retain Rosenbaum to defend conduct that, if proven, would be statutorily non indemnifiable, the City has placed the public in the position of financing a defense against legal predicates that would, by law, prohibit indemnification. The continuity of Rosenbaum’s prosecutorial history, his present role as a public records enforcement litigator, and his current taxpayer funded defense of a former police chief accused of records obstruction collapses the conceptual firewall between public accountability and private exposure.

This is not the appearance of conflict. It is institutional continuity under a different name.

Post Retirement Defense Funding and the Statutory Collapse of the Scope of Employment Predicate

Former Police Chief James McCann formally retired from the Lorain Police Department on or about September 29, 2024. As of that date, McCann ceased to be a current employee of the City of Lorain and became a former public official. Despite this separation from active service, the City has continued to authorize and fund his private legal defense through public funds in a federal civil rights action where McCann is sued exclusively in his individual capacity and faces personal exposure under 42 U.S.C. 1983, Ohio Revised Code 149.351, and Ohio Revised Code 2307.60, with punitive damages expressly pled.

Ohio Revised Code 2744.07(A)(1) authorizes a political subdivision to provide a legal defense only where the employee’s acts or omissions occurred within the scope of employment and only where the employee did not act with malicious purpose, in bad faith, or in a wanton or reckless manner. Retirement does not expand that authority. It constricts it. Once the employment relationship ends, the statute no longer operates as a blanket defensive mechanism. The only remaining legal justification for public defense funding becomes whether the alleged conduct was strictly within the lawful scope of employment and strictly free from bad faith or malicious purpose.

The operative federal complaint pleads precisely the disqualifying elements that collapse that statutory defense as a matter of law. It alleges intentional retaliation for protected speech, coordinated obstruction and concealment of public records in violation of Ohio Revised Code 149.351, interference with statutory licensing processes, and civil liability for injuries arising from criminal acts under Ohio Revised Code 2307.60. Each of those theories, if proven, removes the conduct from the scope of lawful employment and places it into personal liability territory where indemnification is prohibited.

This is not a discretionary gray area. The Supreme Court of Ohio has repeatedly held that statutory immunity and related protections do not apply where conduct is malicious, in bad faith, or outside the scope of employment. Fabrey v. McDonald Village Police Dept., 70 Ohio St.3d 351. Cook v. Cincinnati, 103 Ohio St.3d 80. Where those conditions are ultimately established, public defense funding becomes unlawful ab initio.

By continuing to fund the defense of a retired former police chief accused of intentional constitutional retaliation, records obstruction, and criminally rooted civil liability, the City has moved the defense posture entirely outside the safe harbor of Ohio Revised Code 2744.07. At that point, the expenditure ceases to be a personnel benefit and becomes a public finance act subject to direct taxpayer enforcement, auditor scrutiny, and statutory recovery mechanisms.

Ohio law treats municipal officers as fiduciaries of public funds. When public money is expended without lawful statutory authority, it becomes subject to recovery proceedings and taxpayer restraint actions. State ex rel. White v. Cleveland, 125 Ohio St. 230. State ex rel. Dann v. Taft, 109 Ohio St.3d 364. Once a former official is funded for conduct that is alleged to be malicious or criminal in nature, the City assumes the risk that every dollar paid becomes retroactively recoverable if liability is established.

At that point, the litigation no longer concerns only whether McCann violated the Constitution or state law. It now directly implicates whether public funds were lawfully expended at all. The moment indemnification fails under Ohio Revised Code 2744.07, the defense payments convert into potential unlawful disbursements subject to audit findings, restitution orders, and taxpayer enforcement actions.

That is the posture the City has now entered.

Public Funds, Fiduciary Duty, and the Taxpayer Standing Lens

Public officials act as fiduciaries over taxpayer funds and are prohibited from authorizing expenditures that are not legally permitted. The Supreme Court of Ohio has long recognized taxpayer standing to challenge unlawful public expenditures. See State ex rel. White v. Cleveland, 125 Ohio St. 230, which establishes that taxpayers may enjoin the illegal expenditure of public funds where statutory authority is lacking.

Here, Rosenbaum’s defense is funded under a statute that expressly conditions payment on the absence of bad faith or malicious conduct. At the same time, the federal complaint alleges precisely those disqualifying mental states. That contradiction alone creates a legally reviewable fiduciary breach question. When layered onto Rosenbaum’s deep historical involvement in the most consequential prosecutorial failure in Lorain County history, and his simultaneous prosecution of transparency claims against the County in Barilla, the public funds decision ceases to be a neutral administrative act and becomes a structural governance issue.

Institutional Continuity and the Recycle of Prosecutorial Power

The Nancy Smith prosecution represented a generational institutional failure marked by suppressed evidence, investigative overreach, and executive protectionism. That system collapsed only after sustained litigation and investigative exposure. The present federal civil rights litigation alleges a new generation of institutional retaliation, records suppression, executive shielding, and coordinated investigatory control. The same statutes governing transparency and accountability appear again. The same court systems appear again. The same political offices appear again. The same mechanisms of institutional protection appear again.

By placing Rosenbaum, whose career is inseparably linked to the Nancy Smith collapse and to modern public records enforcement litigation, into the publicly funded defense of a former police chief accused of structurally similar misconduct, the City has recreated institutional continuity rather than institutional reform.

This is not coincidence. It is documented recurrence.

Findings of Fact and Controlling Ohio Supreme Court Authority on Public Defense Funding

Finding of Fact No. 1. Former Chief James McCann is sued in his individual capacity under 42 U.S.C. 1983, Ohio Revised Code 149.351, and Ohio Revised Code 2307.60, with punitive damages expressly pled, placing his alleged conduct outside the statutory conditions for mandatory indemnification under Ohio Revised Code 2744.07.

Finding of Fact No. 2. Former Chief McCann formally retired from the Lorain Police Department on or about September 29, 2024. The City of Lorain is now funding the private legal defense of a former official rather than a currently serving employee.

Finding of Fact No. 3. Ohio Revised Code 2744.07(A)(1) authorizes discretionary defense funding only where the alleged acts occurred within the scope of employment and were not committed with malicious purpose, in bad faith, or in a wanton or reckless manner. The federal complaint alleges intentional retaliation, public records obstruction, and criminally rooted conduct, all of which are statutorily disqualifying if proven.

Finding of Fact No. 4. In Fabrey v. McDonald Village Police Dept., 70 Ohio St.3d 351, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that immunity and related statutory protections do not apply where the conduct is undertaken in bad faith or with malicious purpose, confirming that intentional misconduct collapses statutory protection as a matter of law.

Finding of Fact No. 5. In Cook v. Cincinnati, 103 Ohio St.3d 80, the Supreme Court of Ohio reaffirmed that political subdivision immunity and defense protections do not extend to conduct that is willful, malicious, or outside the scope of employment.

Finding of Fact No. 6. Ohio Revised Code 149.351 imposes personal civil liability on public officials who unlawfully destroy, remove, conceal, or alter public records. The statute is punitive and remedial in nature and operates independently of employment status.

Finding of Fact No. 7. Ohio Revised Code 2307.60 creates a civil cause of action for injuries arising from criminal acts, including abuse of office, retaliation, intimidation, and obstruction. Civil liability under that statute is personal and not derivative of municipal employment.

Finding of Fact No. 8. In State ex rel. White v. Cleveland, 125 Ohio St. 230, the Supreme Court of Ohio held that taxpayers possess standing to enjoin unlawful expenditures of public funds where statutory authority is lacking.

Finding of Fact No. 9. In State ex rel. Dann v. Taft, 109 Ohio St.3d 364, the Supreme Court of Ohio reaffirmed that public officials act as fiduciaries over public funds and may be restrained from expending funds in the absence of clear statutory authority.

Finding of Fact No. 10. The City of Lorain has not publicly documented any special counsel appointment, ethics referral, or independent investigatory authorization. The only documented external expenditure is the publicly funded private defense of former Chief McCann by Jonathan E. Rosenbaum.

These findings establish that the statutory conditions permitting public defense funding are in direct legal tension with the allegations pled, the retirement status of the defendant, and the punitive statutory causes of action asserted.

Indemnification Limits Under Ohio Law

Ohio Revised Code 2744.07 governs indemnification and the provision of legal defense for employees of political subdivisions. Under that statute, a public employer may provide a legal defense only where the employee acted in good faith, within the scope of employment, and without malicious purpose, bad faith, wanton misconduct, or criminal conduct. Those statutory conditions are not discretionary factors. They are legal predicates.

The pleadings in this case place every one of those statutory conditions directly into dispute. The verified federal complaint alleges willful First Amendment retaliation, intentional concealment and manipulation of public records, interference with state licensing authorities, abuse of investigatory process, and civil liability arising from criminal acts under Ohio Revised Code 2307.60. Those allegations foreclose any presumption of indemnification at the pleading stage as a matter of law.

If a trier of fact ultimately determines that any defendant acted outside the scope of lawful authority or engaged in wanton, reckless, malicious, or criminal conduct, Ohio law prohibits indemnification. Under such a determination, any public funds expended for personal defense become legally vulnerable to recovery proceedings, taxpayer enforcement actions, auditor review, and additional civil scrutiny regarding unlawful expenditure. The statutory firewall protecting public money collapses once bad faith or criminal conduct is adjudicated.

That is not hypothetical. That is the structure of the statute.

Monell Liability and Structural Conflict

The pending Monell claim alleges that the retaliatory and obstructive conduct at issue reflects official City policy, custom, or practice. Where both the municipality and individual policymakers are defendants in the same case, federal courts recognize that the interests of the public entity and the personal interests of individual defendants do not always align.

When the same officials accused of wrongdoing remain embedded within the authorization chain for defense funding, investigatory control, and administrative oversight, the separation between public defense and private defense becomes factually and legally compromised. This is especially true where defense funding decisions are made by officials who themselves face individual liability in the same case.

The defense funding decision therefore does not exist outside the litigation. It now exists inside it.

Current Posture and the Point at Which Funding Becomes a Factual Issue

At present, no findings of liability have been entered. All defendants are presumed innocent under law. That presumption does not immunize the spending decisions themselves from review. The decision to fund individual legal defenses before the adjudication of the indemnification predicates places the authorization conduct squarely within the factual landscape of the case.

What is established as public record is not speculative. The City is paying to defend individual defendants accused of personal misconduct. The authorization includes officials who are themselves named defendants. Defense counsel selected for the Chief has prior political and legal ties to City leadership and prior City litigation. Executive coordination with the Sheriff and Prosecutor regarding complaints filed by Knapp is documented. Mayoral involvement in the McCann administrative investigation is documented. The former Chief is now retired while his defense continues to be funded with public money.

Those are not allegations. Those are records.

At that point, the litigation is no longer confined to questions of individual liability alone. It now encompasses questions of fiduciary duty, statutory compliance, and the lawful use of taxpayer funds. The defense itself becomes part of the case.

The Legal Boundary Now Being Tested

Ohio law draws a clear boundary between public service and personal exposure. Ohio Revised Code 2744.07 permits defense only under narrow conditions. Ohio Revised Code 149.351 and 2307.60 impose personal civil liability for intentional misconduct. The Supreme Court of Ohio has repeatedly held that immunity and related protections fall away when conduct is malicious, in bad faith, or criminal in nature. Fabrey v. McDonald Village Police Dept., 70 Ohio St.3d 351. Cook v. Cincinnati, 103 Ohio St.3d 80.

When public money is expended on the defense of conduct that, if proven, is legally non indemnifiable, the expenditure itself becomes reviewable. State ex rel. White v. Cleveland, 125 Ohio St. 230. State ex rel. Dann v. Taft, 109 Ohio St.3d 364.

That is the legal boundary now being tested in real time.

What This Case Now Represents

This case no longer concerns only whether individual defendants violated the Constitution or state law. It now tests whether a municipality can lawfully deploy taxpayer funds to defend personal exposure while the statutory conditions for that defense remain directly disputed. It tests whether executive control over investigations and defense authorizations can persist without independent separation when the same officials populate both sides of the transaction. It tests whether public funds can continue to flow where the law expressly withdraws that protection upon a finding of bad faith.

Those issues do not arise in rhetoric. They arise in statutes. They arise in Supreme Court precedent. They arise in the invoices paid with public money while the legal predicates for payment remain unresolved.

That is the real posture of this case now.e legal advice. All defendants are presumed innocent unless and until proven otherwise in a court of law.

The Oversight and Compliance Phase Now Triggered

At this stage, the federal litigation no longer operates solely as a civil adjudication of individual misconduct. The City of Lorain’s continued authorization of public funds for the private legal defense of a retired former police chief accused of intentional constitutional retaliation, public records obstruction, and criminally rooted civil liability activates a separate and independent layer of statutory oversight under Ohio law.

Ohio Revised Code 2744.07 conditions the lawful use of public funds for defense and indemnification on the absence of malicious purpose, bad faith, wanton misconduct, or criminal conduct. Ohio Revised Code 149.351 imposes personal civil liability for unlawful destruction, removal, concealment, or alteration of public records. Ohio Revised Code 2307.60 authorizes civil recovery for injuries arising from criminal acts. These statutes do not operate in isolation. When they intersect with ongoing public expenditures, they place the expenditures themselves within the scope of compulsory compliance review.

The continued payment of public funds under statutory authority that collapses upon a finding of bad faith or criminal conduct creates a contingent liability for the municipal treasury. If the underlying conduct is ultimately adjudicated to fall outside the protections of Ohio Revised Code 2744.07, every dollar expended for personal defense becomes subject to recovery under Ohio public funds doctrine. At that point, the issue is no longer discretionary. It is one of statutory misapplication.

Under Ohio Revised Code Chapters 117 and 733, the Office of the State Auditor and municipal taxpayers each possess independent authority to examine, restrain, and seek restitution for unlawful public expenditures. The Supreme Court of Ohio has repeatedly affirmed that public officials act as fiduciaries of public funds and may be restrained when statutory authority is exceeded. State ex rel. White v. Cleveland, 125 Ohio St. 230. State ex rel. Dann v. Taft, 109 Ohio St.3d 364.

Where public money is used to defend conduct that, if proven, is legally non indemnifiable, the defense payments themselves become a live compliance issue. The legality of the underlying defense authorization shifts from internal administrative discretion into the jurisdiction of external fiscal oversight. That jurisdiction includes audit findings, recovery actions, and judicial enforcement.

At that point, the question is no longer whether the defendants will prevail on the merits of the civil claims. The question becomes whether public funds were lawfully deployed at all. That determination is not reserved to political leadership. It belongs to statutory auditors, courts of law, and the taxpayers whose funds were expended.

The record that now exists establishes three fixed points. Individual defendants face personal liability for alleged intentional misconduct. The City remains exposed under Monell liability. Public funds continue to be expended under a statute that withdraws protection upon a finding of bad faith or criminal conduct. That triad places the defense funding decision itself into the scope of mandatory public accounting.

This case has therefore crossed a structural threshold. It is no longer confined to civil rights adjudication alone. It now squarely implicates public finance law, fiduciary duty, statutory indemnification limits, and taxpayer enforcement authority.

From this point forward, the matter does not resolve only in pleadings and motions. It resolves in audit reports, compliance determinations, recovery proceedings if warranted, and judicial findings on the lawful use of public money. That is the phase the City of Lorain has now entered.

The Public Record Now Demands Public Accounting

At the point where public money is being used to defend a retired former official accused of intentional constitutional retaliation, public records obstruction, and criminally rooted civil liability, the legal analysis leaves the courtroom and enters the domain of municipal finance and public trust. Ohio Revised Code 2744.07 does not permit open-ended defense funding where bad faith and criminal conduct are squarely alleged. Ohio Revised Code 149.351 and 2307.60 impose personal liability that cannot be absorbed by taxpayers if proven. The Supreme Court of Ohio has made clear that unlawful expenditures are not insulated by political discretion and that taxpayers possess standing to demand judicial restraint of such spending. When these statutes intersect with documented executive coordination, dual defendant authorization chains, and the continued funding of private defense after retirement, the matter ripens beyond litigation strategy and into a question of government accounting. From this point forward, the record no longer concerns only whether the underlying acts occurred. It concerns whether public funds were lawfully deployed at all. That determination will rest not only with the federal court, but with auditors, lawmakers, and the public itself.

Byline

Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, LSW

Investigative Journalist, Government Accountability Reporter

Editor in Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker

Public Records Litigant and Research Analyst

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

Legal Disclosure and Notice

This publication is based entirely upon publicly available court filings, sworn pleadings, administrative records, public records produced or withheld pursuant to Ohio Revised Code 149.43, correspondence released through statutory request, and matters of public record. All factual assertions are drawn from those sources or from documents referenced herein and identified for independent verification.

This article constitutes journalistic reporting, legal analysis, and protected commentary on matters of public concern. It is not legal advice. Nothing contained herein is intended to serve as legal counsel, create an attorney client relationship, or substitute for independent legal advice from a licensed attorney.

All individuals and entities referenced are presumed innocent of any wrongdoing unless and until proven otherwise in a court of law. Allegations referenced herein reflect the contents of pleadings and filings as they exist at the time of publication. The reporting of allegations does not constitute an assertion of ultimate liability.

Any opinions expressed are constitutionally protected expressions based on disclosed facts and public records. Readers are encouraged to review the source documents directly and reach their own conclusions.

This publication is issued in the public interest for purposes of transparency, accountability, and civic oversight consistent with the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution.