The Motion the Court Never Answered

How a Filed Accusation of Judicial Bias Failed to Receive a Reviewable Docket Disposition and Why That Silence Undermines Judicial Authority

When the Record Fails, Authority Becomes Unverifiable

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, LSW

Investigative Journalist, Government Accountability Reporter

Editor-in-Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker (LSW)

Public Records Litigant & Research Analyst

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

Courts do not earn legitimacy through reputation, tenure, or the assumption that judges act in good faith. They earn legitimacy through records that can be examined, challenged, reviewed, and appealed. Every exercise of judicial authority is supposed to leave a paper trail that shows what was filed, what was considered, what was decided, and why. That is not an administrative preference. It is the mechanism that separates lawful power from unchecked discretion. When the record becomes incomplete, inconsistent, or selectively silent, the problem is no longer about a disputed ruling. It becomes a question of whether the court itself can still be trusted to accurately reflect what occurred within its own proceedings.¹

When the record becomes incomplete, inconsistent, or selectively silent, the problem is no longer about a disputed ruling.

This story arises from Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc., a case filed in the Lorain County Court of Common Pleas involving a homeowner asserting statutory consumer protections under Ohio law following defective home improvement work, and a contractor and related entities seeking to enforce a contract and pursue foreclosure.² The plaintiff, Dennis Schlessman, brought claims under Ohio’s Consumer Sales Practices Act and Home Solicitation Sales Act, statutes that provide consumers with cancellation rights, rescission remedies, and explicit limits on enforcement when contracts are obtained or performed in violation of law.³ Plaintiff’s counsel, Robert J. Gargasz, presented those claims through detailed pleadings and a comprehensive trial and mediation brief grounded in Ohio Revised Code 1345.09, which provides that statutory rescission voids the underlying contract and eliminates the supplier’s ability to enforce it, including through foreclosure.⁴ The presiding judge was Melissa Kobasher.⁵

After the court dismissed all statutory consumer protection claims while allowing the supplier’s foreclosure posture to survive, plaintiff’s counsel did not simply register disagreement or proceed directly to appeal. He filed a Motion for Reconsideration and Correction of Error and requested recusal.⁶ That motion alleged that the court’s ruling could not be reconciled with controlling Ohio law, that statutory mandates had been disregarded, that foreclosure had been permitted in direct contradiction of rescission principles, and that the outcome reflected extreme bias, prejudice against counsel, and unethical considerations unrelated to the facts and law of the case. Whether one agrees with the substance or tone of those allegations is not the threshold issue. The filing itself carried institutional consequences. A motion of that nature must be docketed and must receive a documented procedural disposition so that litigants, reviewing courts, and the public can determine how the allegation was handled.⁷

A motion of that nature must be docketed and must receive a documented procedural disposition so that litigants, reviewing courts, and the public can determine how the allegation was handled.

That did not occur in a manner reflected by the contemporaneous public record. During a defined and critical period, documented through retained docket history and access captures, the motion was not reliably reflected on the docket and did not receive a disposition that produced a traceable, reviewable public record.⁸ There is no contemporaneous entry showing receipt during that period, no order denying reconsideration, no order addressing recusal, and no written explanation resolving the allegations.

Although the motion later appeared on the docket, that belated visibility did not cure the defect. No ruling followed. No disposition was entered. The record still contains no explanation resolving the allegations. At the same time, the case continued forward. Chambers issued entries. The court exercised authority over subsequent proceedings. Communications between counsel treated the motion as operative, including a demand from opposing counsel for a copy and an expressed intent to pursue a motion to strike, conduct incompatible with a filing that did not exist.⁹ Proceedings advanced as though the motion both existed and did not exist at the same time. That contradiction is not rhetorical. It is a record integrity failure.¹⁰

Proceedings advanced as though the motion both existed and did not exist at the same time.

Judges are permitted to be wrong. They are permitted to misapply statutes. They are permitted to issue rulings that appellate courts later reverse.¹¹ What the system does not permit is the absence of a reviewable docket disposition for a filed motion that challenges the court’s impartiality and ethical compliance. Without a ruling, there is nothing to appeal. Without reliable docketing during the period when review rights attach, there is no transparency. Without documented disposition, there is no accountability.¹² When a court proceeds while such a motion remains procedurally unresolved in the record, judicial legitimacy no longer rests on law. It rests on silence.

When a court proceeds while such a motion remains procedurally unresolved in the record, judicial legitimacy no longer rests on law. It rests on silence.

This story is not about whether Judge Kobasher should have granted reconsideration or recused herself. Reasonable minds can disagree about bias, statutory interpretation, and judicial error.¹³ In Ohio, disqualification of a common pleas judge is typically pursued through the statutory procedure set forth in R.C. 2701.03, which makes accurate docketing and documented handling of filings alleging judicial bias especially critical. A filing that implicates that process must leave a visible procedural footprint showing how the court treated it, whether by referral, rejection, or other documented action that preserves review.

This story is about why a motion accusing the court of bias and ethical failure failed to receive a timely, reviewable docket disposition, why that failure occurred during the period when it mattered most, and what it means for the judicial system when the record stops functioning as a reliable account of judicial action. When a court file cannot be trusted to show what was filed and how it was resolved, authority itself becomes unverifiable, and that failure extends beyond the parties to the integrity of the system itself.

A Clean Record Before the Break

Before the motion that later became the center of the docket problem, the case file was notable precisely because it looked ordinary in the best sense of the word. Plaintiff’s counsel did not begin this litigation by attacking the court, probing boundaries, or loading the docket with accusations. The filings reflected conventional, methodical advocacy rooted in Ohio consumer protection law. The Plaintiff’s Trial and Mediation Brief presented a structured analysis of alleged violations under the Consumer Sales Practices Act and the Home Solicitation Sales Act, anchored in Ohio Revised Code 1345.09 and related statutory provisions. The brief explained the mechanics of statutory rescission in plain terms, laid out why rescission voids the underlying contract, and articulated why foreclosure cannot lawfully proceed once a home improvement contract has been cancelled under the statute. It identified the remedies the statutes expressly contemplate and relied on appellate authority, including Ninth District law, as the governing framework the trial court was asked to apply.

Just as important as what the brief contained is what it deliberately did not contain. There was no personal criticism of the presiding judge. There were no allegations of political animus, ethical failure, or improper motive. The court’s integrity was not questioned. The brief assumed neutrality, competence, and institutional regularity, and it proceeded from the baseline expectation that when statutes are presented clearly and precedent is cited accurately, the court will engage with the law and explain its reasoning on the record. In tone and substance, the filing reflected respect for the institution and confidence in the process, not hostility toward it.

It begins with ordinary litigation conduct, presented in a way that would typically lead to an ordinary litigation outcome: a ruling that can be evaluated, challenged if necessary, and reviewed through normal appellate channels.

That context matters because it establishes baseline credibility before the record fractured. This was not a case launched as a public campaign against the bench. The record does not begin with inflammatory rhetoric or serial attacks on judicial legitimacy. It begins with ordinary litigation conduct, presented in a way that would typically lead to an ordinary litigation outcome: a ruling that can be evaluated, challenged if necessary, and reviewed through normal appellate channels. When later events introduced confusion about what was filed, when it was visible, and whether it was ever procedurally resolved, that confusion did not arise out of a long-standing pattern of conflict with the court. It arose after a conventional presentation of statutory claims, followed by an adverse ruling that counsel believed could not be reconciled with the statutes invoked, followed by a procedural silence that prevented the normal mechanisms of review from functioning as designed.

In other words, the escalation that followed is best understood as a reaction to a perceived breakdown, not as the starting posture of the case. What follows does not begin with a lawyer looking for a fight. It begins with a lawyer who expected the law to be applied, the docket to reflect what was filed, and the system to function the way courts of record claim they function: through traceable entries, documented decisions, and a reviewable paper trail.

The Moment the Record Broke

The Motion That Should Have Forced an Answer and Instead Produced Silence

What changed this case was not disagreement with a ruling. It was the filing of a motion that the judicial system cannot lawfully ignore, followed by the absence of any traceable, reviewable record showing how the court acknowledged or handled it. A Motion for Reconsideration and Recusal is not a casual filing. It is not correspondence to chambers and it is not rhetorical posturing. It is a formal procedural demand that requires the court to confront a direct challenge to its own legal reasoning and impartiality. Once such a motion is filed, the system has an obligation to process it in a way that leaves a visible procedural footprint. That obligation exists regardless of whether the motion is persuasive, overstated, ultimately rejected, or deemed improper. Silence is not among the available options.

Once such a motion is filed, the system has an obligation to process it in a way that leaves a visible procedural footprint.

The motion at issue alleged that the court issued a ruling that could not be reconciled with Ohio Revised Code 1345.09, that foreclosure was permitted to proceed despite statutory rescission that voided the contract as a matter of law, and that the outcome reflected bias and prejudice against counsel rising to the level of an ethical concern. It requested two forms of relief only. It asked the court to reconsider a ruling asserted to be legally indefensible, and it asked the presiding judge to recuse herself from further proceedings. Those requests triggered well established procedural expectations. The court could deny the motion summarily. It could strike it as improper. It could refer the disqualification question through the channels contemplated by Ohio law. It could issue a written explanation rejecting the allegations. What it could not do was proceed as if the motion never existed.

And yet that is what the docket reflects during the critical period when review rights attach. The motion was not reliably entered in a manner that allowed contemporaneous verification. There was no docket notation showing receipt when it mattered. There was no order denying reconsideration. There was no order addressing recusal. There was no written explanation resolving or rejecting the allegations. The absence is not subtle or partial. It is complete. The motion did not fail on the merits in the record. It failed to exist in the record in a way that produced a disposition capable of review.

What is extraordinary here is not that a motion accused a judge of bias. What is extraordinary is that the record never shows the court answering it.

That absence becomes more troubling when viewed alongside the surrounding conduct of the parties and the court. Opposing counsel acknowledged the motion’s existence by demanding access to it and threatening to move to strike it if it was not properly produced. Court staff continued to issue entries moving the case forward. Chambers communications continued. The litigation proceeded as though the case posture was fully understood. Everyone behaved as if the motion had been filed. But the docket, the only authoritative public account of what the court received and how it acted, told a different story. It showed nothing. That contradiction cannot be dismissed as a harmless clerical oversight without explanation, because clerical errors are corrected through entries. Here, no corrective entry appears. No nunc pro tunc clarification appears. The silence persists.

This is where the issue crosses from alleged legal error into institutional failure. The docket is not a convenience tool or a courtesy log. It is the mechanism by which litigants preserve appellate rights and by which the public verifies that courts are operating within procedural bounds. When a motion alleging judicial bias is not reliably docketed and not dispositioned during the period when review is possible, the practical effect is to foreclose scrutiny. Without a ruling, there is nothing to appeal. Without a traceable entry, there is no way to establish that the issue was ever formally before the court. The absence does not merely disadvantage a litigant. It insulates the challenged conduct from review.

Courts do not have discretion to neutralize uncomfortable filings by declining to acknowledge them. Judicial legitimacy depends on the principle that challenges are met with reasoned responses, not erased through omission. A court confronted with an allegation of bias must either reject it on the record or take the procedural steps required by law to address it. Doing neither creates the appearance that the court has placed itself beyond challenge, which is precisely the condition judicial ethics rules are designed to prevent.

The missing motion matters because it is the hinge on which everything else turns. If the motion was properly filed and not addressed, the court failed to carry out its procedural obligations. If it was received and not reliably docketed during the critical period, the integrity of the record is compromised. If it was later made visible without disposition, the failure remains unresolved. Each possibility raises a different question, but all lead to the same conclusion. A filing that should not have been capable of disappearing was never explained.

This is not a dispute about tone, civility, or aggressive advocacy. Courts encounter sharply worded motions every day and deny them routinely. What is extraordinary here is not that a motion accused a judge of bias. What is extraordinary is that the record never shows the court answering it. In a system that claims legitimacy through transparency, unanswered accusations do not simply fade away. They remain unresolved, calling into question not only the ruling that preceded them, but the integrity of the process that followed.

The Ruling That Made No Sense

The court’s dismissal of all Consumer Sales Practices Act and Home Solicitation Sales Act claims while simultaneously permitting the supplier’s foreclosure posture to remain intact was not merely an adverse outcome for the plaintiff. It was an outcome that is difficult to reconcile with the statutory framework governing consumer rescission in Ohio. Under Ohio Revised Code 1345.09, rescission is not framed as a discretionary equitable preference that a court may apply or withhold based on circumstance. It is a statutory consequence that voids the underlying contract as a matter of law once the statutory conditions are satisfied. When a home solicitation contract is rescinded, the legal relationship created by that contract ceases to exist. A voided contract cannot supply the legal foundation for enforcement, collection, or foreclosure, because all such remedies presuppose the continued existence of a valid, enforceable agreement. Foreclosure is not an independent cause of action detached from contract validity. It is entirely derivative of enforceability.

Judicial authority does not rest on infallibility. It rests on traceability.

The court was presented with this framework clearly and repeatedly. The pleadings and trial and mediation briefing explained the mechanics of statutory rescission, identified the notice and timing requirements imposed by the Home Solicitation Sales Act, cited Ohio appellate authority addressing the effect of rescission, and articulated the legal consequence that once rescission occurs, the supplier is barred from enforcing the contract or pursuing remedies that flow from it. Allowing foreclosure to proceed after rescission is not a marginal interpretive dispute or a close question of statutory construction. It collapses the distinction between a void contract and a merely contested one. It treats statutory cancellation as functionally meaningless. It renders mandatory consumer protections optional in practice. In doing so, it produces a result that the General Assembly enacted the statute to prevent.

When a court reaches a result that appears to contradict both the statutory text presented and the precedent cited, without explaining how that contradiction is resolved, counsel is placed in a genuine ethical and professional bind. Lawyers are not permitted to disregard apparent legal error simply because it originates from the bench. At the same time, they are not entitled to presume misconduct from every adverse ruling. The system provides a narrow and structured mechanism to navigate that tension. Counsel may accept the ruling and preserve the issue for appeal, or counsel may ask the court to reconsider and correct the error at the trial level before the consequences become irreversible. Where a ruling permits foreclosure to continue despite asserted statutory rescission, that second option is not merely strategic. It becomes a professional obligation to protect the client from ongoing harm that cannot later be undone.

That context matters because it explains what followed. The filing of a motion for reconsideration was not escalation for its own sake. It was the predictable and ethically required response to a ruling that, as written, could not be squared with Ohio law as presented. Counsel did not immediately accuse the court of bias or impropriety. He invoked the corrective process the judicial system itself provides for addressing alleged legal error at the trial level. The motion that followed was not performative. It was the direct consequence of a ruling that, if left unchallenged, would have reduced statutory consumer protections to empty words while allowing enforcement mechanisms to proceed as though rescission had never occurred.

The Motion That Should Have Changed Everything

The Motion for Reconsideration and Correction of Error marked the point at which this case moved from ordinary litigation into territory the judicial system is specifically designed to confront rather than avoid. The motion did not hedge its language or soften its conclusions. It alleged that the court’s ruling could not be reconciled with governing law and instead reflected extreme bias and prejudice against plaintiff’s counsel, the influence of considerations unrelated to the facts or controlling statutes, and an intentional disregard of mandatory provisions of Ohio Revised Code 1345.09 that bar enforcement and foreclosure once rescission has occurred. It did not seek clarification or supplemental explanation. It asked the court to correct what was asserted to be a fundamental legal error and to address whether the presiding judge could continue to preside consistent with the appearance of impartial adjudication.

Whether one agrees with the tone or substance of that filing is irrelevant to its procedural significance. Courts are not insulated from sharply worded motions, particularly where statutory rights and foreclosure consequences are implicated. This was not an informal complaint, correspondence to chambers, or an off-the-record grievance. It was a formal pleading bearing counsel’s signature, properly captioned, served on opposing counsel, and represented as filed with the court. In procedural terms, it was among the most consequential filings a party can submit at the trial court level because it directly challenged the court’s impartiality and demanded an on-the-record response. Motions of this kind require disposition. They must be denied, granted, struck, or otherwise addressed in a way that preserves transparency and appellate review. They cannot be nullified through inaction.

Motions of this kind require disposition. They must be denied, granted, struck, or otherwise addressed in a way that preserves transparency and appellate review. They cannot be nullified through inaction.

For a critical period, however, the motion did not exist where its existence mattered most. It was not reliably reflected on the docket. There was no contemporaneous entry acknowledging receipt. There was no order denying reconsideration. There was no ruling addressing recusal. There was no explanation stating that the allegations were rejected, procedurally improper, or declined on any stated basis. The public record was silent. In a court of record, silence is not a neutral condition. It is an affirmative absence that deprives litigants of reviewable rulings and deprives the public of the ability to verify how judicial authority is exercised. The failure of the docket to reflect the filing and disposition of this motion is not a minor irregularity. It is the point at which the integrity of the record itself is called into question, because courts do not retain legitimacy by allowing the filings that most directly test their neutrality to pass without trace or resolution.

The Missing Entry Problem

This is the point at which the case stops being about disagreement with a ruling and becomes a question of institutional integrity. Courts are not evaluated solely by the substance of their decisions, but by whether their records accurately reflect what occurred. The legitimacy of judicial authority depends on the reliability of the docket, because the docket is the court’s official memory. When that memory becomes incomplete, inconsistent, or contradictory, the problem is no longer adversarial. It is systemic.

Opposing counsel’s response to the Motion for Reconsideration is critical because it provides independent confirmation that the motion was understood to exist within the case. Opposing counsel did not deny that a motion had been submitted. She did not accuse plaintiff’s counsel of inventing a filing. Instead, she demanded a copy of the motion and threatened to move the court to strike it if it was not properly produced. That posture only arises when a filing is perceived as real but procedurally irregular, inaccessible, or defective in form. Lawyers do not threaten to strike documents that do not exist. They threaten to strike documents that exist but cannot be located or reviewed through ordinary channels. That distinction matters because it shows the motion occupied a recognized, if anomalous, position within the litigation.

At the same time, the court itself continued to function as though it possessed full awareness of the case posture. Chambers issued entries. The civil assistant circulated communications to all counsel. The presiding judge continued to exercise authority over the matter, signing orders and allowing proceedings to move forward without interruption. There was no pause in judicial control and no notation that a significant motion was pending but unresolved. There was no entry indicating uncertainty about the status of recent filings. The machinery of the court continued to operate normally, as though the record before it was complete.

That juxtaposition creates a contradiction the record never resolves. Either the motion was submitted for filing or it was not. If it was not, opposing counsel’s demand for a copy and threat to strike it are inexplicable. If it was submitted and received, the absence of a contemporaneous docket entry acknowledging receipt or disposition reflects a failure of record integrity. If it was submitted, received, and known to the court, the absence of any ruling addressing reconsideration or recusal represents a procedural omission that directly impairs review. Each possibility raises a different concern, but all of them lead to the same conclusion: the court file cannot be relied upon to accurately reflect what occurred during the critical period when review rights attach.

The missing entry is not a footnote to this case. It is the point at which the record stopped functioning as a record, and where silence displaced the transparency that judicial legitimacy requires.

These are not rhetorical questions designed to provoke outrage. They are mechanical questions that go to the basic operation of courts. Judicial systems live and die by mechanics, because mechanics are what transform authority into law. A court that cannot reliably show what motions were presented and how they were handled cannot credibly claim that its decisions are subject to correction, accountability, or appellate oversight. The missing entry is not a footnote to this case. It is the point at which the record stopped functioning as a record, and where silence displaced the transparency that judicial legitimacy requires.

Constructive Knowledge Becomes Actual Knowledge

There is a point in any judicial proceeding where plausible deniability ceases to exist, not because of speculation or inference, but because the court’s own conduct makes ignorance implausible. Once a motion accusing the presiding judge of bias and ethical misconduct has been circulated, treated as operative by opposing counsel, and exists within the active litigation environment, constructive knowledge gives way to actual institutional awareness. Courts do not operate in sealed compartments where chambers can manage a case, issue entries, and move proceedings forward while remaining unaware of filings that directly challenge the court’s impartiality. Active case management presumes familiarity with the contents of the case file as a whole, particularly filings that implicate the judge’s authority to continue presiding.

That reality is underscored by what happened after the recusal motion was submitted. Chambers continued to issue entries. Court staff communicated with counsel. Orders were signed. Proceedings advanced without pause, reservation, or notation of uncertainty. Those actions are inconsistent with a court that lacks awareness of its own docket posture. They reflect ongoing judicial control exercised on the assumption that the record before the court was complete and current. In that context, ignorance is no longer a credible explanation for the absence of a response to a motion of this magnitude. What remains is silence.

At this stage, silence is not an oversight. It is a choice.

At this stage, silence is not an oversight. It is a choice. The record contains no order denying the motion for reconsideration. It contains no order addressing or denying the request for recusal. It contains no explanation rejecting the allegations, no clarification that the motion was untimely or procedurally improper, and no notation indicating that the court considered and declined to act. The absence is comprehensive. The motion did not fail on the merits in any recorded sense. It was not denied after consideration. It simply ceased to exist in the only place where judicial truth is preserved.

In a court of record, motions do not vanish on their own. They are either entered and ruled upon, or entered and disposed of through some documented mechanism. When a motion alleging judicial bias disappears without acknowledgment while the court continues to exercise authority over the case, the disappearance itself becomes the most consequential act. It transforms what could have been a contested but reviewable dispute into an unreviewable silence. That transformation is not neutral. It deprives the litigants of a ruling to appeal, deprives oversight bodies of a clear record to examine, and deprives the public of assurance that challenges to judicial conduct are met with transparency rather than omission.

Once constructive knowledge ripens into actual institutional awareness, silence no longer preserves neutrality. It undermines the integrity of the process the court is charged with safeguarding.

Why This Matters More Than Any Ruling

Judges are permitted to be wrong, and the judicial system is built on the expectation that error will occur. Courts issue rulings that appellate courts reverse every day, sometimes narrowly and sometimes emphatically. That process is not a failure of the system. It is the system functioning as designed. What the system does not tolerate, and cannot survive, is a record that becomes unreliable as an account of what was filed, what was considered, and how disputes were resolved. Judicial authority does not rest on infallibility. It rests on traceability. When the record cannot be trusted, the legitimacy of every ruling that follows is placed in doubt, regardless of whether those rulings are substantively correct.

A wrong ruling can be appealed and corrected. A missing record cannot.

A missing motion alleging judicial bias and ethical impropriety is not a clerical inconvenience or a technical defect that can be dismissed as harmless. It is a structural failure that strikes at the core of procedural justice. Such a motion is not filed merely to persuade the trial judge. It exists to create a reviewable record. It forces transparency. It ensures that allegations directed at the court itself are either addressed, rejected, or preserved for appellate or disciplinary review. When that motion disappears from the docket without explanation and without disposition, the litigant is deprived of the ability to appeal because there is no ruling to challenge. The public is deprived of transparency because there is no official account of how the court responded. Oversight bodies are deprived of a clear record because there is no documentation showing that the issue was ever confronted.

What remains in the absence of a reliable record is inference. Observers are left to reconstruct events from emails, conduct, and circumstantial gaps rather than from authoritative entries and orders. That condition is corrosive to a judicial system that claims legitimacy through documentation rather than discretion. Courts do not earn trust by insisting that their actions were proper. They earn trust by leaving behind records that allow others to verify that claim. When a court file omits a material filing and offers no explanation for its absence, it forces every interested party to guess what occurred. In a system of law, guessing is unacceptable.

This is why the disappearance of the motion matters more than the correctness of any single ruling issued in this case. A wrong ruling can be appealed and corrected. A missing record cannot. Once the paper trail stops telling the full story, the system loses the very mechanism it relies upon to correct itself. At that point, the harm extends beyond the parties involved and beyond the outcome of one case. It undermines confidence in the process itself, because a court that cannot be trusted to maintain an accurate record cannot credibly demand deference to its authority.

The Question No One Answered

And the Moment Silence Became Intentional

The central issue raised by this case is not whether the presiding judge should have granted reconsideration or recused herself. Reasonable lawyers, judges, and observers can disagree about the merits of a recusal request or about whether a ruling reflects legal error rather than judicial discretion. The judicial system is designed to accommodate that disagreement through written orders, reasoned explanations, and appellate review. Those mechanisms exist so that contested decisions can be evaluated, corrected, or affirmed within a transparent and orderly framework.

The problem here is more basic and more troubling. A filing alleging judicial bias and ethical impropriety entered the litigation environment, was acknowledged, disputed, and escalated through official channels, yet was not docketed and dispositioned in a reviewable manner during the critical period in which appellate rights and procedural accountability depended on a traceable public record.

By October 10, 2025, plaintiff’s counsel stated in writing that the Motion for Reconsideration and Correction of Error had been filed. Defense counsel treated it as such, demanding copies, disputing access, and threatening to move the court to strike it. On October 13, 2025, defense counsel escalated that dispute and copied John Gill of the Lorain County Clerk of Courts, placing the Clerk’s Office on direct notice that a motion was being treated as operative but was not readily accessible. That same day, plaintiff’s counsel directly communicated with Magistrate John Gill and copied defense counsel, transmitting a Notice of Authority and continuing to press the underlying statutory issues.¹⁴

What followed was not clarification of the record, but something far more consequential.

Rather than disputing whether a motion had been filed, Magistrate Gill expressly refused to engage with the substance of counsel’s communications and warned that if counsel wished to bring matters to the court’s attention, he must “file a motion with the court.” That admonition is notable not for its tone, but for its implication. It presupposes that the proper vehicle for raising concerns is a motion, even as the record already reflected an active dispute over the existence, accessibility, and procedural handling of a motion counsel asserted had been filed.

Counsel was instructed to “file a motion” while simultaneously dealing with opposing counsel and the Clerk over the existence and accessibility of a motion that was already being treated as operative and that later appeared on the docket.

At no point in that exchange did Magistrate Gill state that no motion had been filed. At no point did he clarify that the Clerk had not received it. At no point did he direct counsel to refile, correct a deficiency, or cure a procedural defect. Instead, the response sidestepped the filing question entirely while warning of sanctions for continued communication outside formal motion practice.

This created a contradiction the record never resolved. Counsel was instructed to “file a motion” while simultaneously dealing with opposing counsel and the Clerk over the existence and accessibility of a motion that was already being treated as operative and that later appeared on the docket. The system was aware of the dispute. The Clerk was copied. The magistrate responded. Yet no official clarification of filing status, no corrective docket entry, and no documented disposition followed.

Although the motion later appeared on the docket, that belated visibility did not cure the defect. There remains no order denying reconsideration, no order addressing recusal, and no explanation resolving the allegations. The filing exists in the record only in its raw presence, not in a form that shows how the court treated it. The court continued to issue entries and exercise authority while the most serious procedural challenge in the case remained unresolved in any reviewable way.

In Ohio, disqualification of a common pleas judge is typically pursued through the statutory process set out in R.C. 2701.03, which makes accurate docketing and documented handling of filings alleging judicial bias especially critical. Any filing that implicates that process must leave a visible procedural footprint showing whether it was referred, rejected, or otherwise acted upon in a manner that preserves review.

This is not a matter of tone or professional disagreement. It is a structural failure of recordkeeping and response. If the filing was procedurally improper, it should have been struck or rejected with explanation. If it was properly filed, it required disposition. If it was inaccessible due to clerical error, the Clerk was in a position to correct that error once notified. None of those things occurred.

The unanswered question, then, is no longer hypothetical. It is concrete. Why did a filing alleging judicial bias, acknowledged by defense counsel, copied to the Clerk, addressed indirectly by a magistrate, later visible on the docket, and never resolved through a reviewable entry or order, remain procedurally unresolved?

Until that question is answered, nothing else in this case can be evaluated with confidence. Arguments about the correctness of the underlying ruling, the tone of counsel’s filings, or the propriety of escalation are secondary to the threshold issue of whether the court’s record accurately reflects what occurred and how the court responded when its impartiality was challenged.

Courts resolve disputes through records. When the record documents awareness without disposition, acknowledgment without resolution, and later appearance without explanation, it deprives litigants, reviewing courts, and the public of the ability to determine what happened and why. In that environment, analysis gives way to inference, and inference is incompatible with a system that claims legitimacy through documentation rather than silence.

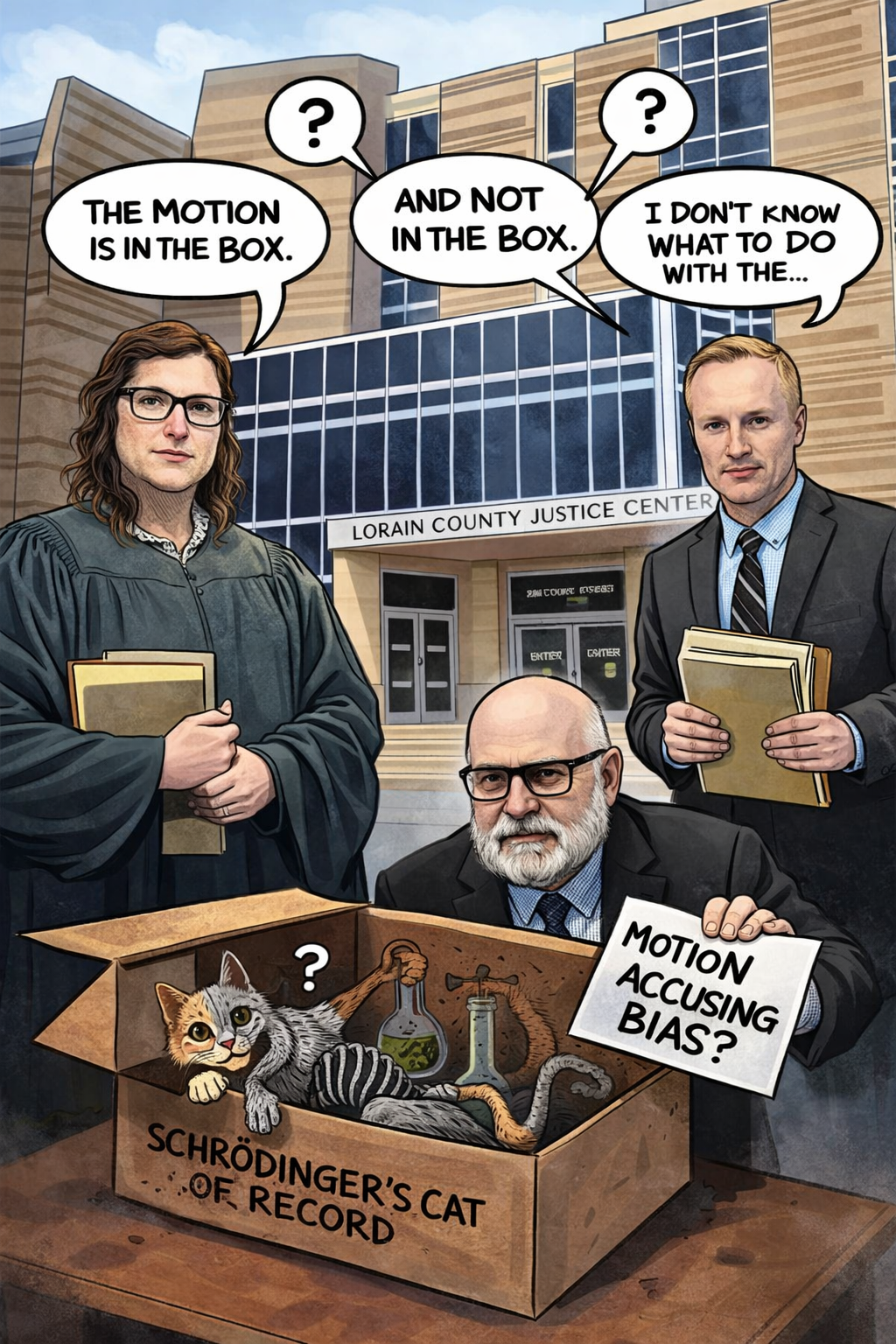

Schrödinger’s Cat in a Court of Record

There is an analogy from physics that exists for one purpose: to describe a condition that cannot logically persist once observation is required. Schrödinger’s cat is the classic illustration. A cat is placed into a closed box with a mechanism that may or may not kill it. Until the box is opened and the system is observed, the cat is described as occupying two mutually exclusive states at once, alive and dead, not because reality tolerates contradiction, but because the observer has been denied the single act that resolves it. The thought experiment is unsettling precisely because it demonstrates how uncertainty can be manufactured by insulation rather than by truth.

In ordinary life, you open the box. In a system governed by law, the equivalent act of observation is the docket. Opening it is not optional. The defining feature of a court of record is that uncertainty does not survive contact with the public file.

The defining feature of a court of record is that uncertainty does not survive contact with the public file.

That is why the contradiction in this case is not rhetorical. It is structural. The motion is treated as real by the participants, yet is not reliably reflected as real by the record during the period when procedural clarity mattered most. Opposing counsel demands a copy and threatens to strike it, conduct that presupposes the filing exists and requires procedural handling. The court continues issuing entries and exercising authority over the case, conduct that presupposes a complete and knowable case posture. Yet the docket, the only official instrument that converts events into reviewable legal history, provides no contemporaneous confirmation that the motion was received, entered, or procedurally resolved.

The result is a procedural version of Schrödinger’s box. The motion is simultaneously treated as operative and treated as absent, acknowledged through conduct and inaccessible through the record. In any other institutional setting, such a contradiction would be resolved through documentation. In a court of record, the docket is supposed to be that act of observation, the mechanism that collapses ambiguity into verifiable fact.

Here, that collapse does not occur. The motion’s existence is inferred through behavior, correspondence, and adversarial response, yet its procedural status never becomes visible where it must become visible for review to function. A motion of this magnitude cannot remain in a suspended state because appellate review depends on traceable disposition, not implication. Oversight depends on documentation, not reconstruction. Public confidence depends on records, not assumption.

When the docket fails to resolve the contradiction, the court does not merely leave a question unanswered. It creates a condition in which the question cannot be answered at all, because the system’s own record refuses to commit to a single account of what occurred.

That is the heart of the problem. The unanswered question is not simply whether the motion was granted or denied, or even whether the judge was biased. The deeper question is why the system permitted a record condition in which two mutually exclusive procedural realities remained simultaneously plausible. Either a motion challenging impartiality entered the case in a manner requiring procedural handling, or it did not. Either it existed as a pending demand for action, or it did not. Either it was procedurally defective and should have been rejected with explanation, or it was valid and should have been addressed.

A court of record is not a place where such contradictions are tolerated. It is the place they are resolved, on paper, in public, with a timestamp and an entry that allows review. When that resolution does not occur, the motion becomes the cat, the docket becomes the closed box, and silence becomes the mechanism that preserves manufactured uncertainty.

In physics, uncertainty can be a feature of the model. In a courthouse, uncertainty is a defect in the record.

When Silence Becomes the Story

“Judges can be wrong or right. They can even be reversed. They are not above ethical challenge within our system of justice. But the justice system depends on the record showing what happened and how challenges were handled. When a motion has been filed and exists in practice but not in disposition, the problem is not the motion. It is the silence. Courts are entitled to reject arguments, deny motions, and rule against parties. What they are not entitled to do is allow a filed motion challenging judicial impartiality to exist without a reviewable disposition. A filed motion may not disappear from the docket for any period without explanation to the parties and the public. This article does not ask anyone to accept allegations at face value. It asks a much narrower and more important question: whether the public record accurately reflects what was filed and how the court responded. When a docket fails to answer that question, the issue is no longer advocacy or disagreement. It is record integrity. And record integrity is foundational to judicial authority.”

Robert J. Gargasz, counsel of record in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc.,

Robert J. Gargasz, counsel of record in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc., stated:

“Judges can be wrong or right. They can even be reversed. They are not above ethical challenge within our system of justice. But the justice system depends on the record showing what happened and how challenges were handled. When a motion has been filed and exists in practice but not in disposition, the problem is not the motion. It is the silence.

Courts are entitled to reject arguments, deny motions, and rule against parties. What they are not entitled to do is allow a filed motion challenging judicial impartiality to exist without a reviewable disposition. A filed motion may not disappear from the docket for any period without explanation to the parties and the public.

This article does not ask anyone to accept allegations at face value. It asks a much narrower and more important question: whether the public record accurately reflects what was filed and how the court responded. When a docket fails to answer that question, the issue is no longer advocacy or disagreement. It is record integrity. And record integrity is foundational to judicial authority.”

Judicial misconduct does not always announce itself through overt acts, hostile exchanges, or authority abused in plain view. More often, it appears in quieter and more corrosive forms that are easier to overlook and harder to confront. It manifests through omissions rather than actions, through absences rather than statements, and through records that no longer align with the events they are meant to document. A missing docket entry, an unaddressed motion, or the absence of a ruling where one is required can be just as consequential as an openly improper act, because the legitimacy of the judicial system depends not only on what judges do, but on what the record shows they have done.

In a court of record, disappearance is not a neutral condition. It is a breakdown.

This case does not present a single dramatic moment that can be isolated and condemned. It presents something more subtle and more troubling. It presents the unresolved disappearance of a motion that accused the court itself of bias and ethical failure, a motion that was treated as operative by opposing counsel, circulated within the litigation environment, and yet never acknowledged or resolved in the official record. In a court of record, disappearance is not a neutral condition. It is a breakdown. Courts exist to produce written explanations for the exercise of power. When a filing of this magnitude vanishes without explanation, the absence itself becomes the most probative fact in the case.

That is why the missing motion sits at the center of this story. Not because its disappearance alone proves intent, corruption, or malice, and not because silence by itself establishes misconduct. It matters because it marks the point at which the paper trail ceased to function as a reliable account of judicial action. The integrity of the judicial process depends on the assumption that filings will be reflected, challenges will be addressed, and decisions will be preserved in a form that allows review and accountability. When that assumption fails, the system no longer speaks through law. It speaks through omission.

Once the record stops reliably showing what was filed and how it was handled, the court forfeits the benefit of the doubt that normally accompanies judicial silence. Transparency is not optional in a system that claims legitimacy through documentation. Silence, in this context, is not restraint and it is not neutrality. It is the story itself.

Judge Melissa Kobasher: A Record That Includes Both Deference and Dispute

Judge Melissa Kobasher has presided over a wide range of civil matters in the Lorain County Court of Common Pleas, including consumer disputes, foreclosure actions, and contract cases. Her docket reflects decisions that, in many instances, adhere closely to procedural norms and dispose of cases efficiently. There are rulings in which her application of law has gone unchallenged and where outcomes align with settled precedent. Any honest assessment must acknowledge that fact. Judges who never issue defensible rulings do not remain on the bench, and nothing in the public record suggests otherwise here.

At the same time, Judge Kobasher’s record includes decisions that have generated controversy, particularly in cases involving statutory consumer protections and remedial statutes designed to limit enforcement power when suppliers fail to comply with the law. In several matters, litigants and counsel have argued that her rulings reflect a narrow construction of statutes such as the Consumer Sales Practices Act and the Home Solicitation Sales Act, especially where those statutes impose mandatory consequences such as rescission, fee shifting, or restrictions on foreclosure. These disputes center on interpretation, not personality, and on statutory force, not judicial temperament.

Standing alone, those disagreements do not establish misconduct. Judges are permitted to interpret statutes differently, to reject counsel’s arguments, and to reach conclusions that parties believe are legally wrong. Appellate courts exist precisely to correct those outcomes when error occurs. Disagreement over statutory meaning, even repeated disagreement, remains within the normal bounds of judicial decision-making.

What elevates certain cases into a different category is not the outcome itself, but the court’s response when that outcome is formally challenged through the procedures the system provides. When a ruling is contested through a motion for reconsideration, or when the court’s impartiality is questioned through a recusal request, the integrity of the process depends on what happens next. Those filings are not mere advocacy. They are mechanisms designed to force transparency, preserve review, and ensure that challenges to judicial authority are resolved on the record rather than absorbed by silence.

In most cases, those mechanisms function as intended. Motions are denied, struck, or referred, and the record reflects how the court addressed the challenge. The presence of many routine, well-documented cases on Judge Kobasher’s docket underscores that point. It demonstrates that the court is capable of producing clean records, issuing reasoned orders, and resolving disputes in a manner that preserves appellate review.

The Schlessman case stands apart not because it involved statutory disagreement, but because the record fails at the precise moment when transparency matters most. The issue is not whether Judge Kobasher has issued controversial rulings in other cases. It is whether, in this case, the system failed to do the one thing it must always do when judicial authority is challenged: leave behind a clear, reviewable record showing how the challenge was handled.

That distinction matters. A mixed record of outcomes invites appellate scrutiny. A missing record of response invites institutional concern. This analysis does not ask the reader to infer motive or intent. It asks only whether the record in this case functions the way a court of record is required to function. On that question, Schlessman raises issues that cannot be resolved by reference to Judge Kobasher’s routine cases, because routine cases did not test the system in the same way.

The Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction case is not significant because it involved Judge Kobasher as an individual, but because it exposes a procedural failure that cannot be explained by disagreement over law alone. In that case, the court dismissed Consumer Sales Practices Act and Home Solicitation Sales Act claims while allowing foreclosure to proceed, a result that raised substantive legal questions about the application of Ohio Revised Code 1345.09 and the legal effect of rescission. Those questions were not left to implication or informal objection. They were formally presented to the court through a Motion for Reconsideration and Recusal that alleged statutory disregard, bias, and ethical impropriety.

What distinguishes Schlessman from routine appellate disputes is not the existence of that motion. Courts receive motions for reconsideration and recusal with regularity, and most are denied without incident. What distinguishes this case is what followed. The motion was treated as operative by opposing counsel, referenced in contemporaneous correspondence, and functioned within the active litigation environment. Yet it was not reliably reflected as filed on the docket during a critical period, and it was never addressed through a written ruling denying reconsideration, addressing recusal, or otherwise disposing of the allegations on the record. Despite that absence, the court continued to issue entries and exercise authority over the case.

That silence does not, by itself, establish misconduct. It does, however, raise questions that cannot be resolved by debating the correctness of the underlying ruling alone. When a motion directly challenging judicial impartiality is neither acknowledged nor dispositioned in the record, the issue ceases to be one of judicial discretion and becomes one of institutional accountability. Courts are permitted to be wrong. They are not permitted to leave unanswered, undocumented challenges to their own neutrality while continuing to act as though no such challenge exists.

Why Patterns Matter More Than Individual Outcomes

A single case does not define a judge, and no serious evaluation of judicial conduct should rest on an isolated ruling or outcome. Judicial systems tolerate error, disagreement, and even reversal as part of their design. What warrants closer examination is not whether a judge ruled correctly in one matter, but whether similar procedural anomalies recur across cases in ways that suggest something more than coincidence. Patterns matter because they reveal how a system behaves under pressure, not how it performs in routine or uncontested circumstances.

The purpose of examining Judge Kobasher’s record alongside other cases in Lorain County is not to single her out or to imply misconduct by inference. It is to ask a narrower and more responsible question: whether the procedural breakdown observed in Schlessman appears elsewhere, either in her docket or across the court more broadly, particularly in cases involving statutory consumer protections, foreclosure authority, or challenges to judicial decision-making. If unaddressed motions, unexplained docket gaps, or prolonged procedural silence recur across judges or case types, the issue is more likely institutional than personal.

The opposite conclusion is equally significant. If Schlessman proves to be an isolated failure rather than part of a broader pattern, that finding strengthens confidence in the judiciary rather than weakens it. Transparency is not a one-way instrument. It serves to identify problems, but it also serves to confirm when concerns are unfounded or exceptional. What erodes trust is not the presence of controversy, but the inability of the record to answer basic questions about what was filed, what was considered, and how challenges were resolved.

Courts earn legitimacy not by avoiding scrutiny, but by producing records that allow scrutiny to reach a conclusion. Patterns matter because they determine whether silence is an anomaly or a feature. Until the record provides a clear answer, the question remains open, and openness, not accusation, is the posture this analysis maintains.

A Living Review, Not a Final Verdict

This section is not a verdict on Judge Melissa Kobasher’s career, competence, or character. It is a record-based snapshot grounded in the materials presently available and in the recognition that judicial authority, like all public authority, requires periodic examination. The analysis offered here is necessarily provisional. It will evolve as additional cases are reviewed, as appellate outcomes are issued, and as broader patterns across the Lorain County judiciary either emerge or fail to materialize.

Judges do not operate in isolation, and scrutiny of judicial action should not occur in isolation either. Courts function within institutional systems that include clerks, magistrates, chambers staff, docketing processes, and procedural norms that shape how cases are handled and how records are maintained. Evaluating any one judge without regard to that context risks both overstatement and understatement. A system that resists examination invites suspicion. A system that permits careful, record-based review strengthens its own legitimacy.

This inquiry is not an attack on the judiciary. It is an insistence on accountability in the precise form the judiciary itself demands of others. Courts require parties to preserve records, to meet procedural requirements, and to submit to review based on what the record shows. That same standard must apply inward. Judicial legitimacy depends not only on the substance of decisions, but on the integrity of the record that documents how those decisions were reached, challenged, and resolved.

This review remains open by design. Its conclusions will be shaped by evidence, not assumption, and by documentation, not inference. That posture does not weaken confidence in the courts. It is the mechanism by which confidence is earned.

Examining the Broader Record

What Other Kobasher Rulings Reveal and What They Do Not

Any meaningful evaluation of judicial conduct must look beyond a single case and ask whether the concerns raised appear elsewhere in a judge’s body of work or whether they remain confined to a specific dispute. The materials compiled in the judicial dossier concerning Melissa Kobasher include rulings across multiple civil contexts, including foreclosure actions, consumer disputes, and contract cases. Taken together, those decisions present a mixed record. They include outcomes that align with settled law and procedural norms, as well as rulings that have drawn criticism from litigants and counsel for their treatment of statutory protections and remedial schemes.

In several matters reflected in the dossier, Judge Kobasher issued decisions that resolved cases efficiently and without controversy. These rulings followed standard procedural paths, applied familiar legal principles, and did not generate post-judgment disputes over docketing, record accuracy, or procedural transparency. Those cases matter. They demonstrate that Judge Kobasher is capable of maintaining orderly records, issuing clear decisions, and concluding litigation without unresolved procedural anomalies. Any serious analysis must acknowledge that such outcomes exist and that they undermine any claim that procedural irregularities are universal or inevitable.

At the same time, the dossier reflects a subset of cases in which litigants have raised concerns that resemble those present in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction. In those matters, parties have argued that statutory consumer protections were narrowly construed or effectively neutralized through dismissal, that remedial statutes designed to limit enforcement power were treated as discretionary rather than mandatory, and that foreclosure or collection mechanisms were permitted to proceed despite unresolved statutory defenses. Standing alone, those criticisms do not establish judicial misconduct. Judges are entitled to interpret statutes and to disagree with counsel’s reading of the law. Appellate courts exist precisely to resolve such disagreements.

What elevates certain rulings into a different category is not the substantive outcome, but the procedural aftermath. The dossier includes examples in which post-decision challenges were met with limited explanation or where the record provides little insight into how statutory arguments were weighed and rejected. In those instances, litigants have complained not merely about losing, but about the absence of transparent reasoning sufficient to permit meaningful review. This theme does not appear uniformly across Judge Kobasher’s docket, but its recurrence in consumer and foreclosure-related matters is notable.

The Schlessman case stands apart because it combines substantive controversy with a procedural breakdown that goes beyond disagreement over interpretation. In other cases, the dispute centers on outcome. In Schlessman, the dispute centers on the integrity of the record itself. The disappearance of a Motion for Reconsideration and Recusal alleging judicial bias is not mirrored elsewhere in the dossier in precisely the same form, but the underlying concern about how challenges to statutory enforcement are handled finds echoes in other rulings. That connection does not establish intent or pattern. It does, however, caution against dismissing Schlessman as an inexplicable anomaly without further examination.

Importantly, the dossier does not support a narrative of indiscriminate judicial hostility toward consumers or counsel. Nor does it establish a consistent pattern of ethical violations. What it reveals instead is unevenness. Some rulings exhibit careful engagement with statutory frameworks and produce clean records suitable for review. Others resolve disputes in ways that leave litigants and observers questioning whether statutory mandates received full consideration or whether procedural safeguards functioned as intended. Unevenness is not misconduct, but it is the condition from which accountability questions arise.

That distinction is critical. The purpose of integrating these examples is not to portray Judge Kobasher as uniquely problematic, but to situate the Schlessman case within a broader landscape of judicial decision-making that includes both defensible outcomes and unresolved concerns. The presence of competent rulings strengthens, rather than weakens, the significance of the missing motion. It demonstrates that the procedural failure in Schlessman was not inevitable, which makes its occurrence more consequential rather than less.

Viewed through this lens, the dossier does not deliver a verdict on Judge Kobasher. It delivers context. It shows a judge capable of maintaining proper records and issuing routine decisions, alongside cases where statutory protections appear diminished and procedural transparency thins. The unanswered questions in Schlessman therefore cannot be explained away as mere administrative chaos or systemic incapacity. They must be examined as specific failures within a system that otherwise demonstrates the capacity to function correctly.

That is why this review remains ongoing. As additional rulings are examined and as appellate outcomes develop, patterns may either solidify or dissipate. If the concerns raised here prove isolated, that conclusion should be documented as clearly as the concerns themselves. If they recur across cases or judges, the issue becomes institutional rather than individual. Either outcome serves the public interest.

Aaron C Knapp LSW, BSSW

Judicial authority does not require insulation from scrutiny. It requires records that can withstand it. Integrating these rulings into a coherent profile is not an attack on the bench. It is a recognition that courts, like all public institutions, earn trust through transparency, consistency, and a record that tells the whole story.

Footnoted Case Scope and Record Limitations

This review distinguishes between matters that are fully documented and those referenced only for contextual purposes based on publicly available docket information. The analysis does not assume equivalence across cases and does not draw conclusions beyond what the existing record supports. Where documentation is complete, the discussion is specific. Where review remains preliminary, that limitation is stated explicitly.

The Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc. matter is central to this article because it is the only case for which a complete procedural record is presently compiled, including pleadings, correspondence between counsel, docket history, and post-ruling conduct. In that case, the plaintiff asserted violations of the Consumer Sales Practices Act and the Home Solicitation Sales Act and invoked statutory rescission under Ohio Revised Code 1345.09. The court dismissed all statutory consumer claims while permitting the supplier’s foreclosure posture to proceed, notwithstanding arguments that rescission voided the contract as a matter of law. Following that ruling, plaintiff’s counsel filed a Motion for Reconsideration and Correction of Error and requested recusal, alleging bias, ethical impropriety, and disregard of statutory mandates. That motion was treated as operative by opposing counsel and existed within the active litigation environment, yet it was not reflected as filed on the docket during a critical period and was never addressed through a written ruling. The court continued to issue entries and manage the case without acknowledging or resolving the motion. The significance of Schlessman lies not solely in the substantive ruling, but in the unresolved absence of a reviewable disposition of a motion challenging judicial impartiality.

In addition to Schlessman, a review of publicly available Lorain County Common Pleas dockets presided over by Judge Melissa Kobasher reveals other consumer, foreclosure, and contract matters in which litigants have raised concerns regarding the treatment of statutory defenses and remedial provisions. These matters are referenced only to provide contextual background. They are not fully documented in the present record and are not offered as findings of misconduct or pattern. At this stage, what is notable is not the outcomes themselves, which may ultimately be defensible, but the recurring assertion by litigants that statutory defenses were not substantively engaged in written rulings in a manner that clearly explains their rejection. Unlike Schlessman, these matters do not presently involve documented docket omissions or missing motions.

The same docket review also reflects numerous routine civil cases over which Judge Kobasher presided that concluded without controversy, procedural irregularity, or post-judgment dispute. These cases include contract matters and standard motion practice resolved through ordinary entries that produced clean, reviewable records. Their inclusion here is deliberate. They demonstrate that the procedural failure documented in Schlessman is not an inherent or unavoidable feature of the court’s operations. Rather, it represents a deviation from otherwise functional judicial administration, which makes the breakdown in that case more consequential rather than less.

This section is included to define scope, not to aggregate allegations. Schlessman is documented and specific. Other matters are identified as preliminary context only. Routine dispositions are acknowledged expressly. As additional records are obtained and reviewed, this section may be expanded, narrowed, or revised to reflect what the record ultimately supports. The analysis throughout this article rests on documentation, not inference, and on what the record shows as much as on what it fails to show.

Why These Footnotes Matter

The purpose of these summaries is not to construct an indictment by accumulation or to imply misconduct through volume. Their purpose is narrower and more disciplined. They establish a factual baseline that distinguishes between what is fully documented, what is preliminarily observed, and what remains unresolved in the public record. Schlessman is treated as central because it is supported by a complete procedural narrative. Other matters are referenced only to provide context, not to substitute conjecture for proof. Clean rulings are acknowledged explicitly because credibility depends on accuracy, not selectivity.

This structure allows the record to speak for itself without forcing conclusions the documents do not yet support. It prevents the analysis from drifting into generalization and confines scrutiny to what can be shown, what can be verified, and what can be fairly questioned based on existing materials. Where the record is complete, the discussion is specific. Where the record is incomplete, the limitation is stated plainly.

As additional case files, orders, and appellate materials are obtained, these footnotes may be expanded into full case studies or narrowed if further review warrants it. If future examination shows that Schlessman is an isolated procedural failure, that conclusion will be recorded with the same clarity as the concerns raised here. If it reveals recurring issues across cases or judges, that conclusion will likewise be documented. Either outcome depends on records, not inference.

Judicial review does not begin with accusations. It begins with documentation. It begins with footnotes.

Footnotes and Sources

1. State ex rel. Morgan v. New Lexington, 112 Ohio St.3d 33, 2006-Ohio-6365. This decision addresses the integrity of public records and the obligation of a public office to maintain records that accurately reflect official actions and decisions.

2. Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc., Lorain County Court of Common Pleas, Case No. 24CV211620. All factual statements in this article describing filings, docket entries, judicial assignment, and attorney correspondence in this matter are supported by the pleadings, docket captures, and communications compiled in the consolidated source packet linked at the end of this article.

3. Ohio Consumer Sales Practices Act, Ohio Revised Code Chapter 1345, and Home Solicitation Sales Act, Ohio Revised Code §§ 1345.21–1345.28. These statutes govern consumer transaction protections, cancellation and rescission rights, and remedies applicable to home solicitation and home improvement transactions.

4. Ohio Revised Code § 1345.09. This provision sets forth civil remedies available for Consumer Sales Practices Act violations, including rescission and damages. The discussion in this article reflects the legal arguments advanced in the plaintiff’s trial and mediation briefing and the authorities cited therein, all of which are included in the consolidated source packet.

5. Lorain County Court of Common Pleas case assignment records, Case No. 24CV211620. References to the presiding judge and assignment are drawn from docket entries and court orders contained in the consolidated source packet.

6. Motion for Reconsideration and Correction of Error and Motion for Recusal, filed by plaintiff’s counsel in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc. The descriptions of the motion’s content, allegations, and requested relief are based on the filed motion included in the consolidated source packet.

7. Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct, Rule 2.11 (Disqualification); Ohio Constitution, Article IV, Section 5(C) (Supreme Court authority over judicial disqualification); Ohio Revised Code § 2701.03 (procedure for disqualification of a common pleas judge); In re Disqualification of Celebrezze, 74 Ohio St.3d 1231 (1991). These authorities govern judicial impartiality, recusal, and the procedural handling of disqualification allegations.

8. Lorain County Clerk of Courts docket history and retained access captures, Case No. 24CV211620. These materials document a period during which the motion described in this article was not reflected as filed on the docket as accessed, followed by later docket visibility of the motion. The record does not reflect any corresponding ruling, disposition, or explanatory entry addressing reconsideration or recusal.

9. Correspondence between counsel, Case No. 24CV211620. References to opposing counsel acknowledging the motion’s existence, demanding a copy, and threatening procedural action are supported by emails and related correspondence included in the consolidated source packet.

10. Welsh-Huggins v. Jefferson County Prosecutor’s Office, 163 Ohio St.3d 337, 2020-Ohio-5371. This decision emphasizes the legal significance of complete and accurate public records and recognizes that omissions and failures of record integrity carry institutional consequences.

11. Ohio Constitution, Article IV. This provision establishes the structure of Ohio’s judiciary and the constitutional framework for judicial authority and appellate review.

12. Ohio Revised Code § 2505.02. This statute defines final, appealable orders and governs appellate jurisdiction, which is directly implicated when the record does not contain an order resolving a filed motion.

13. Liteky v. United States, 510 U.S. 540 (1994); Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct, Rule 2.11. These authorities articulate standards governing judicial bias and disqualification and distinguish between adverse rulings and legally cognizable bias.

14. Email correspondence dated October 14, 2025, between plaintiff’s counsel Robert J. Gargasz and officials of the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, with a forwarded response from Magistrate John Gill of the Lorain County Court of Common Pleas. This correspondence documents that court personnel and opposing counsel were contemporaneously aware of disputes concerning a Motion for Reconsideration and Recusal in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc., including challenges to statutory interpretation under Ohio Revised Code § 1345.09, while the docket did not reflect a contemporaneous entry or disposition addressing that motion. The emails are included in the consolidated source packet linked at the end of this article and are cited for notice, timing, and procedural context only, not for the truth of any characterizations or allegations expressed therein.

About the Source Packet

The consolidated source packet linked with this article contains the underlying materials referenced throughout the footnotes and citations, including filed motions, docket access captures, time-stamped court records, and contemporaneous correspondence between counsel and court personnel in Schlessman v. Fraley & Fox Construction, Inc., Lorain County Court of Common Pleas Case No. 24CV211620. These materials are provided to document the procedural posture of the case, the existence and timing of filings discussed herein, and the condition of the public record as accessed during the relevant period.

The source packet is cited for record integrity, notice, and chronology only. It is not offered to establish the truth of any allegations, characterizations, or arguments contained in pleadings or correspondence, but to demonstrate what was filed, when it was treated as operative by participants in the case, how the docket reflected or failed to reflect those filings at specific points in time, and whether any written disposition appears in the public record.

Readers are encouraged to review the source packet directly. The analysis in this article is grounded in the existence, absence, and sequencing of record entries and related communications, not in speculation about intent or motive. Where interpretation or inference is offered, it is expressly identified as such and distinguished from documented fact.

SEE ALL THE FILES, PUBLIC RECORDS, HERE:

https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:VA6C2:8299931b-3d99-47d8-8f5b-3b72ba4b0a5a

Legal Disclaimer and Reader Notice

This publication is provided for general informational and journalistic purposes only. It is not legal advice, it is not intended as a substitute for legal counsel, and it should not be relied upon as guidance for any particular legal situation, strategy, filing, or decision. Nothing in this article creates an attorney client relationship, and no such relationship is intended or implied. Readers who need legal advice should consult a licensed attorney of their choosing. Any references to statutes, rules, case law, court procedures, ethical canons, or legal standards are presented as part of commentary on matters of public concern and are offered for educational and reporting context only.

This article discusses a sitting judge and judicial proceedings. The discussion is based on publicly accessible information, including court docket entries, filings, orders, and related public records, as well as the existence, absence, sequencing, and visibility of record entries as accessed during the relevant period. Where the article references emails, correspondence, docket access captures, or “source packet” materials, those materials are cited and described as documentation of notice, timing, and procedural context. The inclusion of any filing, allegation, argument, or characterization within a court record or correspondence does not mean the author adopts it as true. Pleadings and advocacy filings often contain disputed assertions, and readers should treat them as such. The article distinguishes, to the extent practicable, between documented events that can be verified from the record, and analysis, interpretation, inference, or opinion offered by the author. Any interpretive statements reflect the author’s good faith understanding of the available record at the time of publication.

Nothing in this article is intended to allege criminal conduct by any individual, and nothing should be interpreted as a claim that any person violated the law. This publication does not accuse any judge, court employee, clerk, attorney, party, or public official of wrongdoing as a statement of established fact. Instead, it addresses a record integrity issue as a matter of public interest, focusing on whether the public file reflects a traceable and reviewable disposition of a filed motion, and what that record condition means for transparency and review in a court of record. The article is written from the premise that courts, like all public institutions, are properly subject to scrutiny through documentation, and that public confidence depends on verifiable records rather than assumption.

If you believe any statement in this article is inaccurate, incomplete, or lacks necessary context, you are invited to provide a written correction request with supporting documentation. Corrections, clarifications, and updates will be considered in good faith and, where warranted, will be appended or incorporated with transparent dating and revision notes.

This article is protected speech concerning matters of public concern. It is published in the exercise of rights secured by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution, including the right to investigate, document, comment upon, and criticize the conduct of public officials and the operations of government institutions based on public records and verifiable documentation. The author supports lawful, peaceful accountability and encourages readers to use official channels for any complaints, motions, appeals, or public records requests.

Public Records and Source Materials Notice