When the Record Precedes the Charges

How a Sworn Narrative, a No Contest Plea, and an Unresolved Testimony Problem Collide

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, LSW

Investigative Journalist, Government Accountability Reporter

Editor-in-Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker (LSW) | Public Records Litigant & Research Analyst

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

There is a persistent and deeply misleading assumption in public discourse that a criminal plea wipes the record clean. It does not. A plea resolves criminal exposure for a defendant within the narrow confines of that case. It does not retroactively validate how the case was built, it does not cure defects in how jurisdiction was invoked, and it does not convert sworn testimony into settled or immune truth. When a matter later moves into civil court, the legal focus shifts in a fundamental way. The question is no longer whether a defendant accepted a disposition. The question becomes whether the power of the state was lawfully and truthfully exercised in the first place, what representations were made to a court under oath to justify that exercise of power, and whether those representations were supported by the record at the moment they were made.

That distinction is not academic. It is the dividing line between finality and accountability. Civil litigation exists precisely to examine what criminal proceedings often cannot or do not resolve. It asks whether investigative narratives were constructed honestly, whether sworn testimony reflected evidence rather than interpretation, and whether courts were asked to act on facts or on confidence. A plea may end a prosecution, but it does not insulate the process that produced it from later scrutiny, especially where sworn statements served as the foundation for judicial action.

That is why the testimony of Captain Jacob Morris in the Garon Petty matter continues to resurface, despite repeated efforts to frame the case as finished. Not because the criminal case remains open. It does not. Not because the plea is disputed. It is not. It resurfaces because Morris’s testimony was not incidental or peripheral. It was foundational. It was the mechanism by which an internal complaint was translated into judicial authority. It was the sworn narrative that allowed the state to cross the threshold from allegation to action. And that narrative, once sworn and relied upon, does not disappear simply because the case later closed.

That bridge between allegation and authority remains visible in the record. It can still be examined. It can still be compared against the underlying evidence. And if it does not hold up under that comparison, no plea agreement has the power to make it disappear.

“A plea may end a prosecution, but it does not insulate the process that produced it from later scrutiny.”

The Limits of a No Contest Plea

Garon Petty ultimately entered a no contest plea to reduced charges, a procedural decision that brought the criminal case to an end. Under Ohio law, however, that outcome has a defined and limited effect. A no contest plea is not an admission of liability in subsequent civil proceedings. It does not ratify the state’s version of events, it does not authenticate the investigative narrative presented by law enforcement, and it does not insulate the charging process from later review. Its legal function is narrow. It resolves criminal exposure for the defendant. It does nothing more.

Critically, a no contest plea does not operate as a retroactive seal of approval on how a case was built. It does not cure defects in charging authority, it does not legitimize sworn testimony that may have overstated or mischaracterized the evidentiary record, and it does not convert contested assertions into established fact. Ohio courts have long recognized that civil liability and institutional accountability are separate questions from criminal disposition, governed by different standards and different purposes.

For that reason, civil courts routinely examine pre charging conduct, sworn statements, and investigative decision making even after a plea has been entered. This scrutiny becomes unavoidable where claims such as malicious prosecution, abuse of process, defamation, or civil conspiracy are raised, because those claims turn on intent, knowledge, and the use of legal process itself. A plea may close the criminal file, but it does not close the factual record that preceded it. It simply shifts the forum in which that record is examined.

In practical terms, the plea closes one door while leaving another fully open. That open door leads not back to guilt or innocence, but directly to the sworn record, where representations made under oath can still be tested against the evidence that existed at the time they were made.

“A no contest plea resolves criminal exposure. It does not retroactively validate the investigative process.”

Why Captain Morris’s Testimony Matters

Captain Morris was not a peripheral witness offering background or secondary context. He was the investigating officer whose sworn testimony formed the factual backbone of the case at the probable cause stage in Lorain Municipal Court. His testimony was the vehicle through which an internal complaint was converted into judicial action. In practical and legal terms, that role carries weight. Courts rely heavily on sworn officer testimony when deciding whether legal process should issue, whether charges may proceed, and whether the state has met the minimum threshold required to invoke judicial authority.

At the probable cause hearing, Morris testified with narrative certainty. He told the court that witnesses feared physical harm, that the conduct at issue was aggressive and escalating, that access barriers were knowingly violated, and that video evidence corroborated the accounts being presented. These statements were not incidental descriptions or tentative impressions. They were affirmative factual representations offered under oath to justify the court’s involvement and to support the continuation of the prosecution. Without those representations, the legal basis for proceeding would have been materially weaker.

At the same time, Morris acknowledged significant limitations in his own knowledge and in the evidence available. He testified that he did not hear the words spoken during the interaction at issue. He conceded that no witness could recall specific threatening language. He acknowledged that the available video footage cut off before the alleged escalation and did not capture the substance of what was said. He further admitted that his conclusions were based largely on tone, demeanor, and interpretation rather than on articulated threats or direct personal observation.

That internal tension is the core problem. It is not a dispute over credibility in the abstract, nor a subjective disagreement about how events should be characterized. It is a contradiction contained within sworn testimony itself. The same testimony that asserted fear, escalation, and corroboration also acknowledged the absence of direct evidence necessary to support those assertions. When such contradictions appear in the sworn record at the point where judicial authority is invoked, they do not dissolve with the passage of time or the entry of a plea. They remain embedded in the record, waiting to be examined.

“The same testimony that asserted fear and corroboration also admitted the absence of direct evidence.”

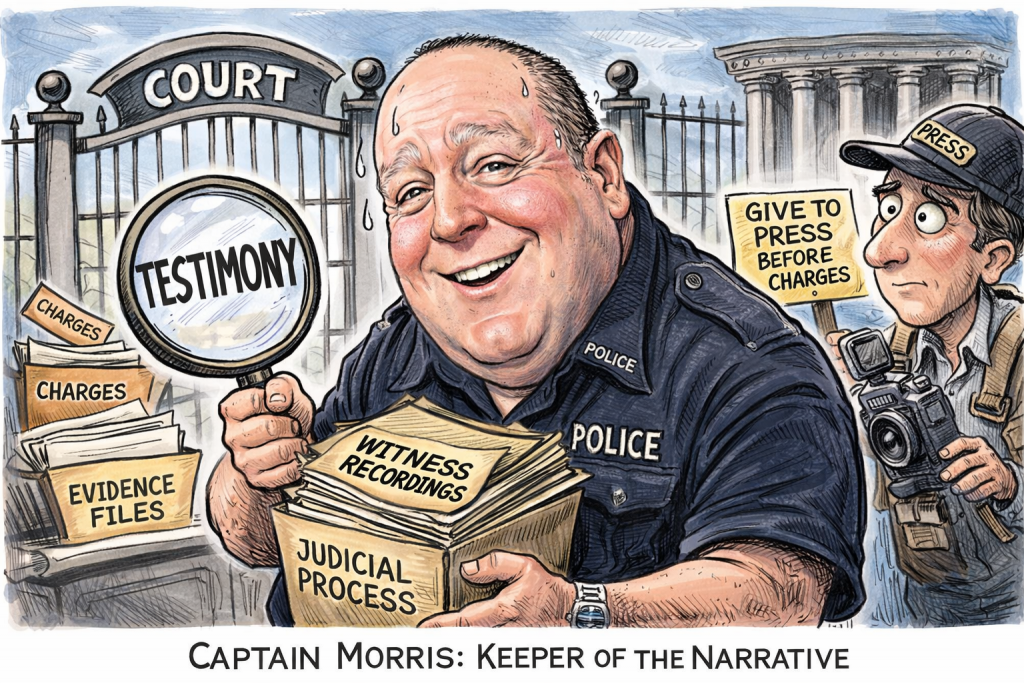

Captain Morris as the Narrative Gatekeeper

Captain Morris’s role in the Petty matter did not end with testifying at a probable cause hearing. He was not merely a conduit for information gathered by others. He was the central gatekeeper of the investigative record. He reviewed the interviews, possessed the recordings, evaluated the available video, and determined how the incident would be framed when presented to the court.

That distinction matters because Morris’s sworn testimony was not delivered in a vacuum. By the time he testified, he had already reviewed the full evidentiary file. He knew what witnesses could and could not say. He knew that no specific threatening language was identified. He knew the limitations of the video evidence. He knew where interpretation began and where direct observation ended.

This was not a case in which an officer later learned of evidentiary gaps. Those gaps were known before charges were filed and before sworn testimony was given.

Morris’s control over the investigative materials also extended beyond internal review. Prior to the filing of any criminal charges, he personally provided a journalist with the full investigative file, including interview recordings and related materials. At the time, no court had reviewed the evidence, no charges had been initiated, and no judicial process had commenced. This disclosure is documented and undisputed.

The significance of that disclosure is not about media access or public records rights. It is about knowledge. It establishes that Morris was fully aware of the content and limits of the evidence at the earliest stages of the case. It confirms that he possessed firsthand familiarity with the very materials he later characterized under oath as corroborative of fear, escalation, and threat.

When an officer with full knowledge of evidenti limitations testifies with narrative certainty, the issue is no longer whether a case was controversial or difficult. The issue becomes whether the court was presented with an accurate depiction of what the evidence could actually support. That question is not resolved by a plea agreement. It is not erased by time. And it is not answered by confidence alone.

In civil litigation, the distinction between interpretation and fact is not cosmetic. It goes directly to whether the machinery of prosecution was used appropriately or whether it was driven by a narrative that exceeded the evidence available at the time. Morris’s role as both investigator and sworn narrator places that distinction squarely at the center of the record.

“When an officer controls the file, reviews the evidence, and testifies with certainty, the question becomes whether certainty exceeded the record.”

The Pre-Charging Disclosure That Changes the Context

There is an additional fact that cannot be set aside because it bears directly on knowledge, timing, and sworn representation. Before any criminal charges were filed in the Petty matter, Captain Jacob Morris personally provided me, in my capacity as a journalist, with the full investigative file. That disclosure included documents and audio recordings of witness interviews that later formed the basis of the prosecution’s narrative. The materials were handed to me directly, prior to the initiation of any judicial process.

At the time of the disclosure, Morris stated words to the effect of, “Chief says give this to you. He knows you’ll put it online.”

No protective order existed. No charges had been filed. No court had reviewed or authorized dissemination of the materials. I did not request early access, preferential treatment, or informal disclosure. The records were provided because the investigating officer chose to provide them.

This fact is not raised as a dispute over public records access. Journalists lawfully receive government records every day, and nothing about this disclosure turns on First Amendment theory. Its significance lies elsewhere. It establishes that Morris had complete familiarity with the evidentiary record before charges were initiated and before he later testified under oath. He knew precisely what the witnesses did and did not say. He knew the limits of the interview recordings. He knew where the evidence ended and where interpretation began.

That knowledge matters because Morris later testified with certainty about fear, escalation, and corroboration. When sworn testimony is evaluated, courts do not ask whether an officer believed a narrative to be compelling. They ask whether representations made under oath accurately reflected the evidence available at the time. The pre-charging disclosure fixes Morris’s knowledge to a specific point in time and removes any ambiguity about whether evidentiary gaps were discovered later or were known from the outset.

In that context, the disclosure does not merely add color to the story. It alters the framework through which the sworn testimony must be understood.

“The disclosure fixes knowledge to a point in time. It removes the excuse of later discovery.”

The Breanna Dull Statement and the Shift in Narrative Authority

The evolution of the Petty case cannot be understood without addressing the role of Breanna Dull’s original sworn statement and how narrative authority later shifted to Captain Morris. That shift matters because it marks the moment when the case moved from a complainant driven allegation to a law enforcement driven theory of criminality.

At the outset, Breanna Dull provided a sworn statement that characterized the incident as felony menacing. That classification is significant. Felony menacing under Ohio law requires the knowing causation of fear of serious physical harm. It is not satisfied by discomfort, annoyance, or generalized unease. It requires articulated facts supporting a specific and serious threat.

Dull’s sworn statement was the foundation upon which the initial characterization of the incident rested. It was her account, not Morris’s observation, that supplied the alleged fear element. At that stage, the case stood or fell on the credibility, specificity, and internal consistency of her statement. Law enforcement did not witness the incident. The allegation was necessarily secondhand.

As the case progressed, however, the narrative center of gravity shifted. The felony menacing theory did not proceed as charged. Instead, the charging posture changed, and with it, the identity of the narrative authority changed as well. Morris became the primary sworn narrator, not merely a summarizer of Dull’s account, but the witness who testified to fear, escalation, corroboration, and intent.

This transition is not a procedural footnote. It is a substantive transformation. When a complainant’s sworn statement is insufficient to sustain a felony charge, the law does not permit certainty to be supplied by confidence or inference. The evidentiary burden remains the same. What changes is who bears responsibility for describing the facts.

In this case, Morris’s testimony did more than relay Dull’s words. It reframed the incident. Fear was no longer described solely as the subjective experience of the complainant. It was presented as an objectively corroborated condition. Escalation was no longer a perception. It was presented as an established fact. Conduct was no longer ambiguous. It was characterized as aggressive and knowingly violative.

Yet the underlying evidentiary constraints did not change. Morris did not hear the alleged statements. Witnesses still could not recall specific threats. The video still did not capture the alleged escalation. What changed was not the evidence, but the narrative voice.

That shift is critical in civil analysis because it raises a straightforward question. When the original sworn statement alleging felony menacing did not sustain the case on its own terms, what justified the elevation of certainty in later sworn testimony? The answer cannot be that the evidence improved, because the record shows it did not. The answer must lie in interpretation.

Civil courts are permitted to examine exactly that kind of shift. Not to second guess charging discretion in hindsight, but to determine whether sworn representations evolved in a way that exceeded the evidentiary record. When an officer’s testimony assumes the role of supplying certainty that a complainant’s statement could not sustain, the officer’s knowledge, framing, and discretion become central issues.

This is not about whether Breanna Dull acted in good faith. It is about how her original sworn statement was transformed into a different theory of criminality without the addition of new, direct evidence. That transformation occurred through Morris’s testimony. For that reason, the relationship between Dull’s original statement and Morris’s later sworn narrative is not ancillary. It is one of the core fault lines in the record.

“What changed was not the evidence. What changed was the narrative voice.”

Why This Issue Persists in the Civil Case

The City of Lorain did not prosecute this matter and then simply return to the status quo. The sworn narrative supplied by Captain Morris was not confined to a courtroom proceeding. It became the justification for a series of operational and policy decisions that extended well beyond the criminal case itself. Those decisions included increased security measures, restrictions on public access, the escorting of employees, the staffing of public meetings with officers, and public characterizations of Garon Petty as a safety concern. None of those actions flowed from the entry of a plea. They flowed from the investigative narrative that preceded it.

When the City now defends those actions in civil court, it necessarily relies on the factual foundation that was used to justify them at the time they were taken. That foundation is Morris’s sworn testimony. The City cannot simultaneously assert that its actions were reasonable and protective while insulating the narrative that purportedly made them necessary from scrutiny. Reliance invites examination.

Civil litigation exists for precisely this purpose. It allows courts to determine whether governmental actions were grounded in objectively reasonable facts or whether they were driven by representations that overstated the evidence available at the time. Where sworn testimony supplied the justification for ongoing restrictions, security changes, and reputational harm, that testimony becomes a live issue regardless of how the criminal case ended.

That is why the Morris testimony does not fade with the passage of time. It is not residual disagreement over a plea. It is an unresolved structural issue embedded in the record. Each time the City attempts to explain or defend what it did, the same question resurfaces. Were those actions supported by what the evidence actually showed, or by how that evidence was described under oath?

“Reliance invites examination. If the City relies on the narrative, the narrative becomes a live issue.”

What Accountability Looks Like Here

Accountability does not begin with accusations. It begins with alignment. Sworn testimony must align with the evidence that existed at the time it was given. Charging decisions must align with what the law authorizes, not what hindsight or narrative framing later suggests. Pre-charging disclosures must align with what is subsequently represented to a court as established fact rather than inference or interpretation.

When those alignments break down, the issue is no longer disagreement or perspective. It becomes institutional integrity.

That is why I will be submitting a notarized Verified Complaint to the Lorain Police Department requesting internal review. The complaint does not allege criminal conduct. It does not demand discipline. It does not seek a predetermined outcome. It documents chronology, sworn statements, pre-charging disclosures, and subsequent representations, and asks a narrow but essential question: whether departmental standards were met at each stage of this process.

This step is not an attempt to relitigate a resolved criminal case. It is an examination of whether the machinery of government was activated on a record that can withstand scrutiny when stripped of narrative gloss and measured against the evidence actually known at the time.

Transparency is not hostility. It is the minimum condition of legitimate authority.

“Accountability begins with alignment. If the record cannot align, the institution cannot demand trust.”

Final Thought

Courts derive legitimacy from records that can be examined, challenged, and reconciled against the evidence that existed at the time judicial authority was invoked. Sworn testimony is the mechanism by which that legitimacy is transmitted from investigators to the bench. When testimony is offered under oath, it is not evaluated based on how persuasive it sounds, but on whether it accurately reflects what the witness knew, what the evidence showed, and what uncertainties remained unresolved.

In the Petty matter, the sworn testimony that supplied probable cause and justified the exercise of state power contains internal tensions that have never been reconciled. Those tensions are not the product of later disagreement or hindsight. They arise directly from the witness’s own admissions under oath regarding what was not heard, what was not recalled, what was not captured on video, and what was inferred rather than observed. The record reflects that these limitations were known before testimony was given and before charges were initiated.

A criminal plea ends a case procedurally. It does not retroactively validate the investigative process that preceded it. It does not cure defects in sworn testimony. And it does not eliminate the public interest in whether the record that justified state action can withstand scrutiny when examined in full.

That scrutiny has not occurred internally. When Garon Petty sought review of the investigative conduct and sworn testimony that formed the basis of the case, the City of Lorain declined to investigate. The police department did not open a substantive inquiry. Instead, Petty was redirected to a generic complaint form, a procedural deflection that did not address the substance of the sworn record or the timing and knowledge issues it presents.

That refusal matters. When an institution declines to examine its own sworn record, the issue does not disappear. It migrates. It moves from internal accountability to public documentation, from closed review to civil litigation, and from discretionary oversight to judicial examination. The question does not change. It only becomes harder to ignore.

This is not about relitigating a resolved criminal charge. It is about whether sworn testimony that invoked the power of the state accurately reflected the evidence as it existed at the time, and whether the institutions responsible for that testimony are willing to examine the record when credible inconsistencies are raised. Record integrity is not optional. It is the foundation on which judicial authority rests.

“When an institution refuses to examine its own sworn record, the issue does not disappear. It migrates.”

Legal Notice and Ongoing Litigation Disclaimer

This publication is provided for informational and journalistic purposes only. It reflects the author’s analysis of public records, court filings, sworn testimony, and related documentation. It is not legal advice and does not create an attorney client relationship. Readers should consult qualified counsel for legal guidance. Allegations remain allegations unless and until proven in a court of law. Matters discussed may involve ongoing litigation and may be updated as the record develops.

AI Image Disclosure

Any illustrative images or graphics accompanying this article may be digitally created, modified, or enhanced, including through the use of AI assisted tools, for commentary and editorial illustration. Such images are not presented as literal depictions of real events unless explicitly stated.

Copyright and Media Rights

© 2026 Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction, redistribution, or republication of this work, in whole or in part, without express written permission is prohibited except for brief excerpts used with attribution for news reporting, commentary, or fair use purposes.