Unmasking the Marsy’s Law Misuse and Multi‐Jurisdiction Records Denials: A Local Journalist’s Fight for Transparency

How County Sheriff’s, City Councils, and Prosecutors Misapply Exemptions to Shield Public Records in Lorain County

Jun 05, 2025

By Aaron C Knapp, Investigative Journalist

Lorain County—and Beyond—Faces Sunshine Law Battles

Lorain County’s public records landscape has been roiled by a series of high‐profile denials. From the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office invoking Marsy’s Law to block communications in what turned out to be a false‐accusation matter, to the City of Lorain withholding Sunshine Law training certificates and council members’ text messages, and finally, the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office refusing to turn over records related to the so‐called “Bring investigation,” local citizens have watched open‐records statutes be stretched to the breaking point. An independent journalist and longtime resident, Aaron C. Knapp, has waged simultaneous fights in the Court of Claims against county and city entities—all in an effort to pry open records that Ohio law clearly designates as public.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Misplaced “Marsy’s Law” and the CLEIRs Claim

In June 2025, Knapp sent a formal request to the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office seeking in‐person inspection of all communications between law enforcement and private citizen Tia Hilton. He believed that any records related to an investigation—whether emails, memos, or phone logs—were subject to Ohio Revised Code § 149.43, which mandates that public records be made “promptly available” unless specifically exempted.

Instead, Sheriff’s Office leadership responded that “Marsy’s Law” protected those communications—despite the fact that no criminal charges were ever filed against Knapp. Under Ohio Constitution Article I, Section 10a and R.C. 2930.07, “Marsy’s Law” can be invoked only when a “victim” in a prosecuted offense formally requests redaction of “case documents.” Knapp’s review of Sheriff’s Report #2025‐10686 confirmed that no charges were ever brought. Because no offense was “committed or attempted” in a court of law, no valid victim status ever materialized, making any Marsy’s Law invocation legally untenable.

At the same time, the Sheriff’s Office insisted that Sergeant Coonrod’s pre‐retirement tablet messages were exempt under the CLEIRs investigatory records privilege (R.C. 149.011(G)). CLEIRs protects only records “compiled for law enforcement purposes” when their release would “impair” an active investigation. In this case, however, Coonrod’s messages were created before he joined any investigative unit, meaning they cannot meet the statutory requirement of being “compiled for law enforcement purposes.”

By citing Marsy’s Law and CLEIRs without specific statutory citations or sworn affidavits, the Sheriff’s Office failed to meet the “written explanation” requirement under R.C. 149.43(B)(3). No county record custodian may rely on vague references to “victim privacy” or “investigatory privilege” without identifying exactly how each requested document fits a statutory exemption.

Knapp’s forthcoming writ of mandamus in the Court of Claims will ask a judge to compel the Sheriff’s Office to produce every withheld record or explain with legal specificity why redactions are warranted.

City of Lorain Holds Sunshine Law Certificates and Council Texts Hostage

Meanwhile, on April 14, 2025, Knapp turned his attention to the City of Lorain. He requested two categories of records: all Sunshine Law, BRIT/PERC, and Diversity training certificates for city council members (as required by Council Rule 41), and all text messages exchanged by Councilmembers Angel Arroyo Jr. and Josh Thornsberry during the April 14 council meeting. Under Ohio Supreme Court precedent—State ex rel. Glasgow v. Jones (119 Ohio St.3d 391, 2008) and Toledo Blade Co. v. Seneca Cty. Bd. of Comm’rs (120 Ohio St.3d 372, 2008)—any text messages related to legitimate public business during an open meeting are public records.

Rather than comply, the Clerk of Council provided a single “generic attendance log” on April 15, omitting all actual training certificates and ignoring the request for text logs altogether. Council Rule 41 specifically requires each member to submit a signed certificate showing completion of Sunshine Law and ethics training; an attendance log does not suffice. For over a month—until May 18—Knapp sent follow‐up emails demanding production or a valid written denial, but the City remained silent.

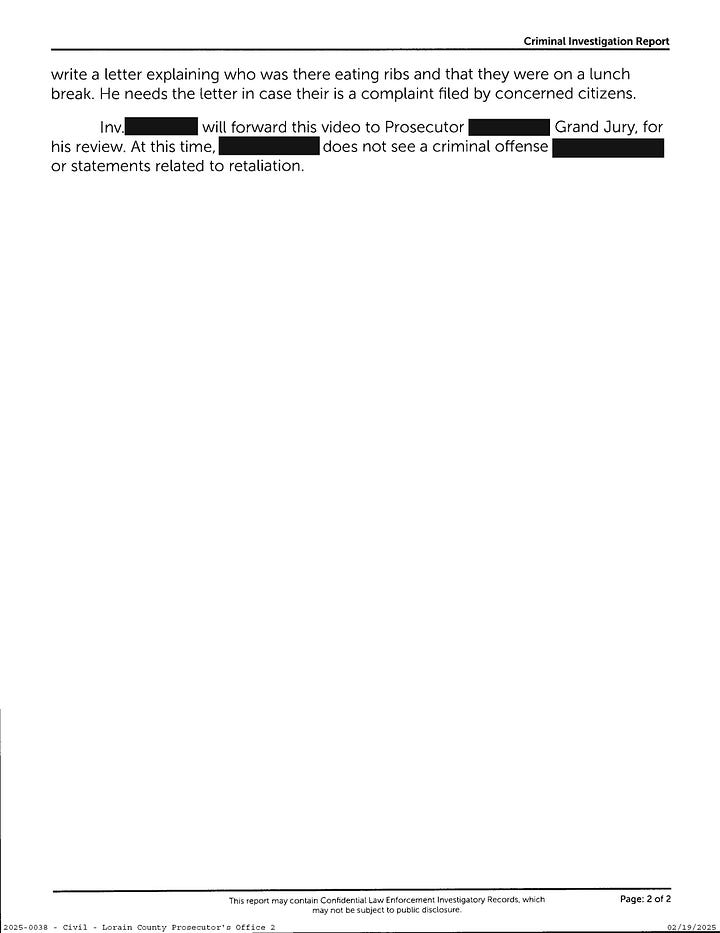

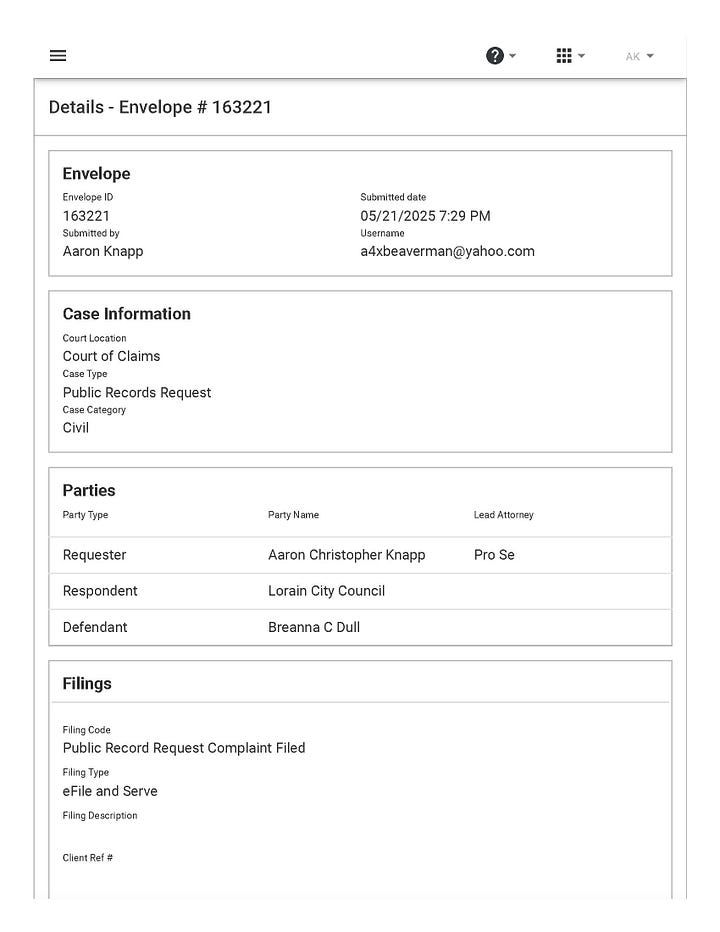

When more than three business days passed without lawful compliance, Knapp served a written “three‐day notice” under R.C. 149.43(C)(1). Still no response came. On May 18, he filed a “Statement of Claim” (Case No. 2025‐0038) in the Ohio Court of Claims, asking a judge to order immediate production of all Rule 41 certificates and all April 14 text messages by Arroyo Jr. and Thornsberry; to reimburse the mandatory $25 filing fee under R.C. 2743.75(F)(3)(b); and to fulfill additional outstanding records requests to City departments (Law, Police, HR, Mayor, Zoning, Auditor, Council staff) within fifteen business days, or face further legal action.

The City of Lorain’s refusal to justify withholding under R.C. 149.43(B)(3) has set the stage for a summary‐judgment motion in the Court of Claims. Unless the City can cite a precise statutory exemption for each withheld record, Ohio law requires disclosure. As argued by Knapp’s filing, any redactions should be limited to purely personal information (phone numbers, personal email addresses, etc.) and should not conceal evidence of potential conflicts of interest, lobbying contacts, or private communications among council members during voting sessions.

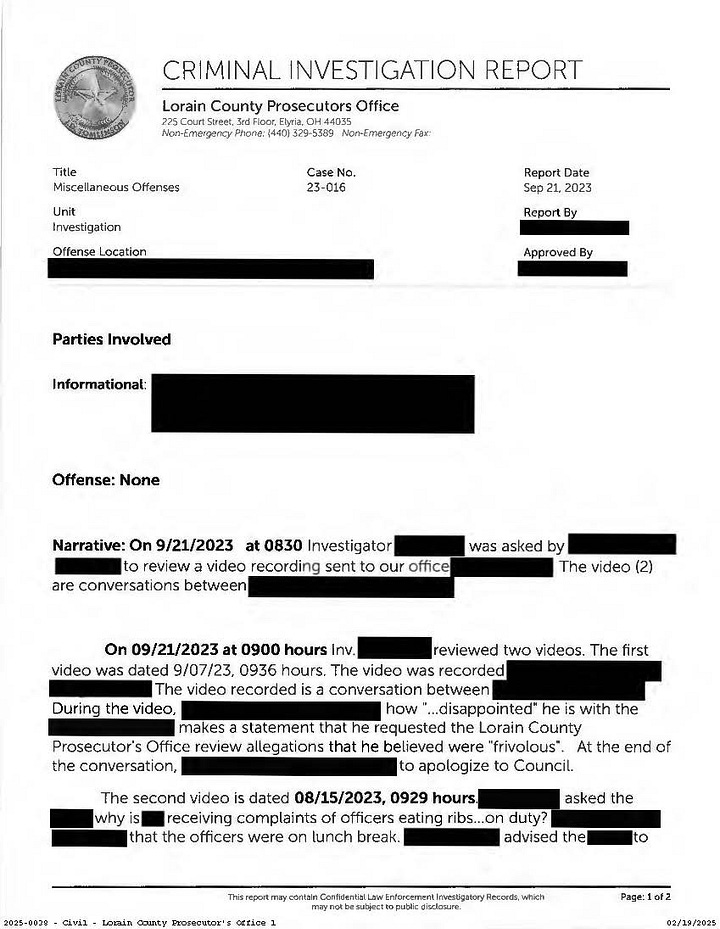

The “Bring Investigation” Records Dispute: County vs. Sheffield Lake

While the Sheriff’s Office and the City of Lorain were firmly in Knapp’s crosshairs, the third front in his transparency crusade involved the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office and the City of Sheffield Lake. In late 2023, the Prosecutor’s Office launched what became known as the “Bring investigation” into allegations of wrongdoing and financial irregularities in Sheffield Lake’s municipal government. Over ensuing months, the Prosecutor’s Office assembled emails, internal memoranda, witness interview transcripts, and consultant reports. Certain files were shared with Sheffield Lake City Hall for collaborative administrative reviews.

Beginning in March 2025, Knapp filed a formal public‐records request with Sheffield Lake City Hall for “all documents related to the Bring investigation received by or generated by the City of Sheffield Lake, including any materials provided by the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office.” Under R.C. 149.43(A)(1), once a public record is “prepared, owned, used, retained, or controlled” by any public office, it must be disclosed unless a narrow exemption applies.

Sheffield Lake responded, with boilerplate emails claiming a broad “prosecutorial privilege,” insisting that, because the records originated at the County Prosecutor’s Office, they were exempt and that Knapp should redirect his request to the prosecutor. In Ohio, however, courts have repeatedly held that if a public document passes into municipal custody, it remains subject to R.C. 149.43. State ex rel. Unite for Reform v. Summit Cty. Prosecutor’s Office (156 Ohio St.3d 1, 2019) clarified that a municipality cannot dodge disclosure by pointing to a third‐party origin.

Unimpressed, Knapp filed a parallel request on May 15, 2025 with the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office, seeking every Bring investigation file in their possession. On May 29, the Prosecutor’s Office issued a terse denial, citing “grand jury confidentiality” under Crim. R. 6(E) and “investigatory privilege” under R.C. 149.43(H), yet offered no document‐by‐document affidavit or in‐camera demonstration. Knapp’s “three‐day notice” on June 1 gave the Prosecutor’s Office until June 4 to comply or substantiate their claims but neither happened.

On June 10, 2025, he filed a Statement of Claim in the Court of Claims (Case No. 2025‐0042) against the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office, seeking immediate production of all Bring investigation records shared with Sheffield Lake, $25 filing‐fee reimbursement, and attorney’s fees under R.C. 149.43(C)(2)(c). Ohio’s law makes clear that grand‐jury and investigatory exemptions must be narrowly applied. Only documents actually presented to a grand jury can be shielded permanently; general investigative material can be withheld only if their disclosure would “seriously impair” an ongoing inquiry. Without that showing, the denial is arbitrary.

Although both Sheffield Lake and the Prosecutor’s Office argue that releasing sensitive documents would hamper fair administration, Ohio courts consistently rule that “public records exemptions are to be narrowly construed” (R.C. 149.43(D)(1)). Any doubt gets resolved in favor of disclosure. Knapp’s ongoing lawsuit aims to prove that neither agency can satisfy its burden under R.C. 149.43, and that a judge should order the immediate release of every “Bring investigation” document that remains unredacted—except for genuine grand‐jury transcripts or privileged communications that meet statutory criteria.

A Systemic Pattern and a Roadmap for Mandamus

Across multiple agencies—Sheriff’s Office, City of Lorain, and Lorain County Prosecutor—Knapp has documented a troubling pattern: public entities citing vague, unsupported “exemptions” rather than complying with multiple R.C. 149.43 requests. Each refusal has followed the same playbook: receive a detailed written request, ignore follow‐ups, send a generic or partial response (or none), and refuse to cite any statutory basis.

Under Ohio Revised Code:

- R.C. 149.43(B)(1) requires that public records be “promptly prepared and made available.”

- R.C. 149.43(B)(3) mandates that any denial be accompanied by a written explanation with the “basis for the denial.”

- R.C. 149.43(C)(1)(b) allows the requester to file a petition for a writ of mandamus in the Court of Claims if a valid denial or production does not occur within three business days after written notice.

- R.C. 2743.75(A) gives the Court of Claims exclusive, original jurisdiction over such disputes once the three‐day cure period has expired.

- R.C. 2743.75(F)(3)(b) requires that, when a requester prevails, the public office reimburse the $25 filing fee.

- R.C. 149.43(C)(2)(c) empowers courts to award “reasonable attorneys’ fees” and any additional damages when an agency “arbitrarily or capriciously” withholds records.

Knapp has followed each step meticulously: he issued clear, written requests citing R.C. 149.43; he waited the mandatory window; he served three‐day notices; and when compliance still did not occur, he filed Court of Claims complaints. In each case, he is poised to move for summary judgment, arguing that no genuine legal exemption covers the withheld documents.

Judges in Lorain County—and across Ohio—have repeatedly confirmed that public officials cannot hide behind vague “Marsy’s Law,” “CLEIRs,” or “privilege” claims. In State ex rel. Young v. Blendon Township, the Supreme Court rejected a township’s misuse of Marsy’s Law. In State ex rel. Unite for Reform, the Court reminded municipalities that records originated by a prosecutor remain public once they enter city custody. And in State ex rel. Colvin v. Cuyahoga Cty. Board of Revision, courts demanded specific affidavits to justify withholding under R.C. 149.43(H).

Knapp’s three concurrent Court of Claims actions send a clear message: Ohio’s Sunshine Laws demand transparency, and any attempt to cloak routine governmental records in secrecy will face vigorous challenge. As each case proceeds toward final judgment, local officials will be forced to reveal the contents of previously concealed documents or face statutory penalties and attorney’s fees.

Conclusion: Shining a Light on Local Government Secrecy

Lorain County and its municipalities stand at a crossroads. Repeated misapplications of “Marsy’s Law,” “CLEIRs,” “prosecutorial privilege,” and generic “attendance logs” threaten to erode the public’s trust in open government. Yet Ohio law remains steadfast: exceptions to disclosure are narrow, and agencies bear the burden of proving each asserted exemption.

By taking his cases to the Court of Claims—first against the Sheriff’s Office (Sheriff’s Report #2025‐10686), then against the City of Lorain (Case No. 2025‐0038), and now against the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office (Case No. 2025‐0042)—Aaron C. Knapp is demonstrating how citizens can enforce their rights under R.C. 149.43 and R.C. 2743.75. Each lawsuit underscores a single truth: transparency is the cornerstone of democracy, and government entities must abide by the law or face swift correction by the courts.

In the coming months, as judges in the Court of Claims evaluate Knapp’s petitions, local officials will have no choice but to confront the plain text of Ohio’s Sunshine Laws. Whether they release unredacted Sheriff’s Office communications, Council Rule 41 certificates and April 14 text messages, or the full Bring investigation files, the outcome will set a precedent: public records belong to the people, not to public‐office convenience.

Ohioans who believe their own records requests have been met with improper denials should take heed. Issue a detailed, written request; insist on a written explanation if denied; serve a three‐day notice; and file in the Court of Claims if compliance still does not materialize. As Knapp’s battles illustrate, courts patiently but firmly enforce the right to know. And in Sheffield Lake, Lorain County, or Lorain, the public will ultimately win when light outlasts secrecy.

References:

- Ohio Constitution, Article I, Section 10a (Marsy’s Law)

- Ohio Rev. Code § 2930.01, 2930.07, 2930.14, 2930.043 (Victims’ Rights statutes)

- Ohio Rev. Code § 149.43 (Public Records Act)

- Ohio Rev. Code § 149.011(G) (CLEIRs investigative exemption)

- Ohio Rev. Code § 149.43(H) (Investigatory privilege)

- Ohio Rev. Code § 2743.75 (Court of Claims jurisdiction)

- Lorain City Council Rule 41 (Sunshine Law training requirement)

- State ex rel. Young v. Blendon Township, Sixth Dist. No. 23CA010598 (Slip Op. Feb. 2024)

- State ex rel. Glasgow v. Jones, 119 Ohio St.3d 391 (2008)

- Toledo Blade Co. v. Seneca Cty. Bd. of Comm’rs, 120 Ohio St.3d 372 (2008)

- State ex rel. Unite for Reform v. Summit Cty. Prosecutor’s Office, 156 Ohio St.3d 1 (2019)

- State ex rel. Colvin v. Cuyahoga Cty. Board of Revision, 150 Ohio St.3d 1 (2017)

- State ex rel. Reno v. Buckeye Local SD Board of Education, 102 Ohio St.3d 196 (2004)

- Sheriff’s Report #2025‐10686 (May 2025)

- Statement of Claim, Case No. 2025‐0038, Court of Claims of Ohio (filed May 18, 2025)

- Statement of Claim, Case No. 2025‐0042, Court of Claims of Ohio (filed June 10, 2025)

- City of Lorain correspondence (Apr.–May 2025)

- Sheffield Lake correspondence regarding the Bring investigation (May–June 2025)