The Rewrite: How Lorain Officials Removed Statements, Invented Dialogue, and Violated Ohio Law

The Clerk says, “We wrote them as we heard them.” Ohio law says accuracy isn’t optional, and the recordings expose what was erased.

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, Investigative Journalist — Unplugged with Knapp

Published on AaronKnappUnplugged.com

There is a point where a mistake becomes misconduct. There is a point where a public record stops being a record and becomes a tool. After what I witnessed this morning inside Lorain City Hall, and after comparing the city’s published minutes with the actual audio and video of the October 20 council meeting, that point has been reached.

This is the follow-up to my earlier report. But today the story became significantly worse. I confronted the Clerk of Council about the false and misleading minutes that she finalized and prepared for certification. At first she said only that “they are written the way we heard them.” I asked how that could be true when the city’s own recording clearly captured Director Rey Carrion’s words. She did not answer. I told her that putting my name in the minutes violates Ohio law and that she has created a false public record. Her response was that she does not want me to put words in her mouth. I did not. I simply told her the law and showed her the record. She refused to correct it.

When a custodian of records knowingly publishes something contrary to the evidence, that is not a misunderstanding. That is a violation of her statutory duty, and depending on the circumstances, it can also constitute falsification of records under Ohio law. And today the Clerk of Council knowingly affirmed a false narrative that she personally knows is contradicted by the city’s own audio and video.

What the Record Shows

The official video feed of the October 20 meeting, the body-mic recording on my phone, and the independent audio Garon Petty captured all show the same sequence with crystal clarity. There is no ambiguity. There is no debate to be had. Director of Public Safety and Service Rey Carrion leaned forward from the dais, turned his body toward me, pointed twice, and said loudly and distinctly, “Did you say something?” He did this while he was the one holding the floor. He did not address the Council President, which is the only person a speaker may address under the Lorain Rules of Council Procedure. He did not frame his question through the chair. He did not adhere to any parliamentary structure. He went directly at a citizen in the gallery. That is the single thing the rules most specifically prohibit him from doing.

Lorain’s rules are not complicated. If a public official has the floor, all remarks must go to the Council President. Full stop. You cannot turn and speak directly to the public. You cannot single out a member of the audience. You cannot start a back-and-forth with a private citizen. The Rules of Council exist to prevent this exact scenario: officials targeting specific individuals from the dais.

But what the video shows is that Director Carrion broke those rules in real time.

What the minutes show is something else entirely.

The minutes erase him. They eliminate his words completely. They pretend the initiating trigger never happened. They present the exchange as if I were talking to no one, because according to the official minutes, no one ever talked to me. They record my quiet, private remark to Garon, “Then why are we?”, as if I shouted it across the room. They record only the last line, and only my line, arranged in a sequence that makes it appear that I spontaneously launched an argument into thin air.

That is not a mistake. That is the definition of falsifying the context of an event.

And there is something even more incriminating. During my earlier public-comment period, the part where I was recognized, and where I came prepared , they transcribed my remarks word-for-word. That is because I had written my comments on paper in advance and read them verbatim. The City captured every sentence, every phrase, every punctuation-mark rhythm. They did not miss a syllable when it came to my statements made from the podium.

So the Clerk of Council is fully capable of capturing a citizen’s remarks accurately and fully. I have now seen the comparison side-by-side: the minutes reflect my written remarks exactly, exactly as I delivered them.

But somehow, the same “accuracy” and “hearing ability” mysteriously evaporated the moment the Safety-Service Director violated the rules and addressed a private citizen directly.

They could hear me perfectly. They could quote me flawlessly. They could transcribe me with courtroom precision. But when the public official turned toward me and said “Did you say something,” suddenly the microphones, the clerk’s perception, and the entire institutional memory of Lorain City Council experienced a sudden, convenient, selective amnesia.

How very interesting.

What was I doing — having a one-sided argument with myself? Whispering into the air? Talking to a ghost? The fiction is obvious, and it collapses the moment you place the minutes beside the recordings. Because all three recordings — my body-mic, Garon’s independent audio, and the city’s own official live feed — capture the exact same sound:

Director Rey Carrion saying, “Did you say something?” Clear as day. Twice.

There is no static. There is no distortion. There is no missing channel. There is no technological issue. The words are there. They were always there. They remain there on every piece of evidence the City tried to pretend did not exist.

So when the minutes erase him entirely and leave only my responses, it is not a clerical oversight. It is not a formatting error. It is not a misunderstanding.

It is deliberate omission.

It is intentional falsification.

It is the rewriting of a public record to protect a city official while shifting blame onto a private citizen who had relinquished the floor, was not participating in the meeting, and was targeted in violation of council rules.

This is exactly the category of misconduct Ohio courts have condemned again and again. A public body cannot omit material events. A public body cannot conceal the actions of its own members. A public body cannot publish minutes that contradict its own audio. These principles are not debatable. They are settled law — and the City of Lorain violated them knowingly, after being shown the evidence.

What the Clerk Told Me Yesterday Morning

During my visit I asked directly whether she understood that placing my full name in the minutes is unlawful. I was not a party to any meeting item. Council minutes cannot identify individual citizens except when someone is formally recognized for public comment. I had already spoken. My public comment had ended earlier. I relinquished the floor. I was no longer a participant. I was just another member of the audience.

Yet my name remained.

I asked her how that could possibly be legal. I asked her why a private citizen’s name had been inserted into an exchange that I did not initiate, did not request, and did not participate in voluntarily. My name appeared because an official addressed me improperly, not because I somehow forced myself into the record. Ohio law does not allow minutes to identify spectators in ways that imply participation or culpability. My name should never have been there.

Her response was that they “wrote them as we heard them.” This is impossible on its face. If she heard me, then she heard Rey Carrion. If she heard my voice, she heard his voice first. If she heard any part of the exchange, she heard the part where he leaned forward, pointed across the dais, and said “Did you say something?” She was seated directly behind him. She watched him do it. She heard it in real time. And she has watched the city’s live-feed video of the meeting. None of this is absent from her knowledge. None of this is ambiguous.

Yet she knowingly removed his statements from the minutes while keeping mine.

She knew what the audio contained. She knew what the video showed. She knew that three independent recordings documented his words. She knew the city’s own official stream captured him speaking first. And she knew that an accurate description of the incident would place responsibility squarely on the Safety-Service Director, not the citizen seated quietly in the gallery.

She chose to scrub him. She chose to retain me. She chose to write a government record in a way that inverts reality and assigns blame to the person who did not start the exchange while shielding the official who did.

That is not how minutes work. That is how narratives work.

That is not clerical work. That is editorial work.

That is not truth. That is construction.

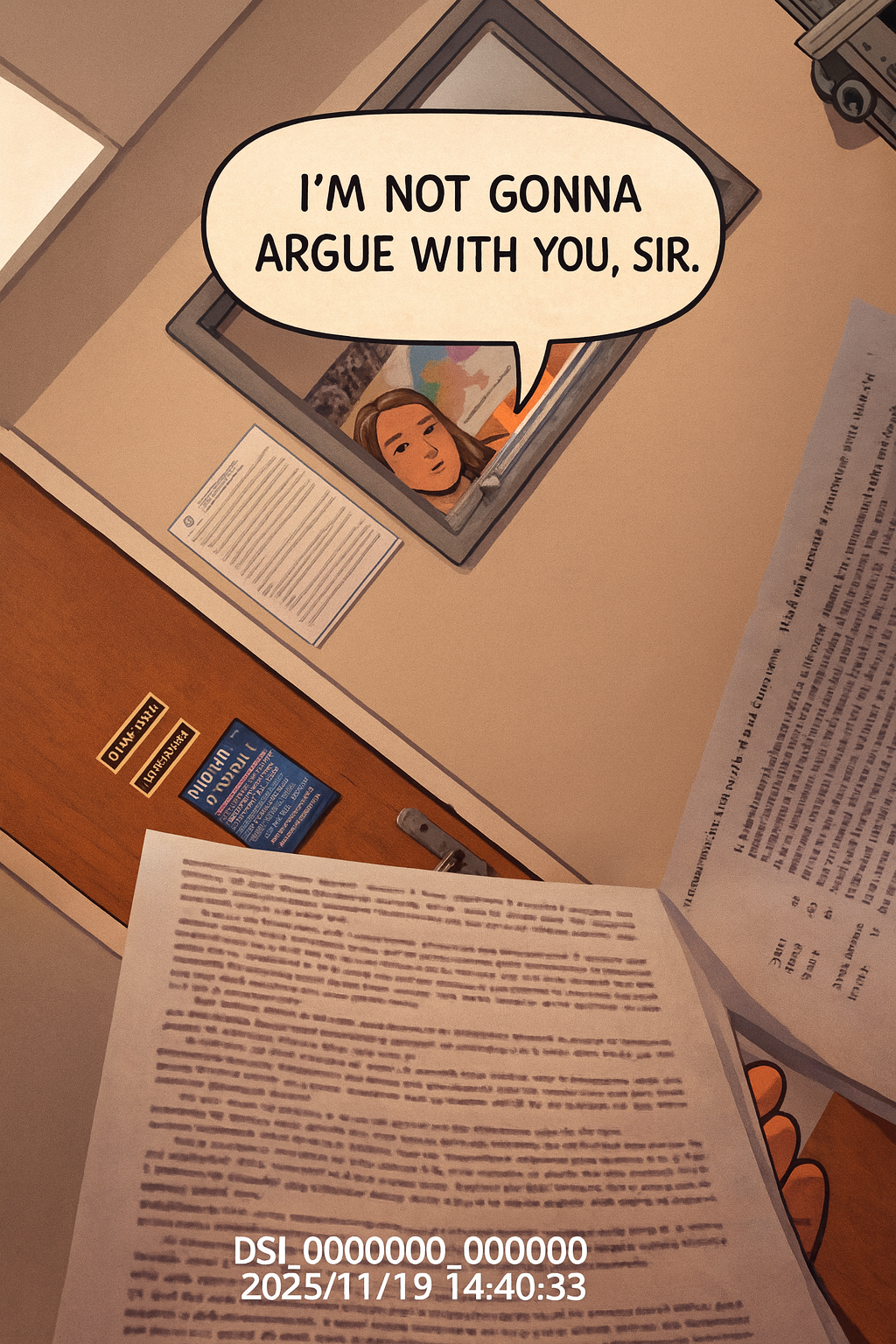

Then she added a line that carries significant legal weight: “I’m not going to argue with you.” She spoke those words in her official capacity as Clerk of Council. She spoke them as the statutory custodian of public records. She spoke them while being confronted with evidence that the minutes she finalized were false, misleading, and contrary to law.

She is a public official. She took an oath to uphold the Constitution and the laws of this state. Her duty is to the truth, not to political convenience. Her obligation is to accuracy, not allegiance. Under Article I, Section 16 of the Ohio Constitution, every person has the right to seek redress from government officials. That is not optional. That is not conditional. That is not subject to the discretion or comfort level of the official being confronted.

A public official cannot refuse redress by declaring she will not “argue” when confronted with the plain text of the law. A clerk cannot shut down accountability with a dismissive slogan. Her job is not to win an argument. Her job is not to avoid discomfort. Her job is to tell the truth and follow the statutes that govern her duties.

The duty to be redressed is not a courtesy afforded by officials. It is a constitutional right owed to the public. A refusal to be redressed is a refusal to perform the essential function of the job.

When a clerk responds to evidence of an unlawful record with “I’m not going to argue with you,” she is not declining argument. She is refusing accountability. She is refusing transparency. She is refusing the constitutional mandate placed upon her office.

A clerk who does not want to be redressed cannot lawfully serve as a clerk.

All Three Recordings Capture the Same Words

The city’s live feed, my body-mic recording, and Garon’s independent recording each captured the entire exchange from three different physical angles and three different audio sources. None of them conflict. None of them are ambiguous. None of them leave room for interpretation. Each one, without exception, contains Director Rey Carrion leaning forward, turning toward the gallery, pointing, and twice saying the exact same phrase: “Did you say something?” He said it loudly. He said it clearly. He said it while holding the floor, during active legislative business, in direct violation of the city’s own procedural rules. These three recordings form a triangulated evidence set: the city’s official feed shows the visual actions, my body mic captures the room audio near the dais, and Garon’s recording captures the sound from the gallery side. Together they create a complete factual picture that does not bend or change depending on who is watching. They show the same moment, the same violation, and the same initiating act. They show exactly who started the exchange. And they show that it was not me.

When three independent recordings align this perfectly, the probability of mistake drops to zero. We are not dealing with a clerical mishearing. We are not dealing with an accidental omission. We are not dealing with something that could be chalked up to confusion or cross-talk in a crowded chamber. You cannot accidentally fail to hear a department head yelling twice. You cannot accidentally delete only the words spoken by the city official while preserving every word spoken by the citizen he confronted. You cannot accidentally erase the initiating conduct but keep the reaction—for no reason other than narrative convenience. When the only missing element is the government actor’s misconduct, and the only preserved element is the citizen’s response, the omission becomes a choice. It becomes deliberate. It becomes intentional falsification.

And that is precisely what the minutes show. They remove Rey Carrion completely, as if he never spoke, as if he never turned, as if he never broke the rules he is sworn to follow. They leave my quiet response stripped of context, suspended in the air, presented as if I had simply decided to challenge nobody in particular. What was I doing according to their record—having a one-sided conversation with myself? The fiction becomes obvious the moment any person compares the published minutes to even one of the recordings. The fiction becomes undeniable when all three recordings confirm the same sequence of events. And the fiction becomes indefensible when the custodian of records is aware of the recordings, has access to them, and still publishes a narrative that contradicts what the microphones captured.

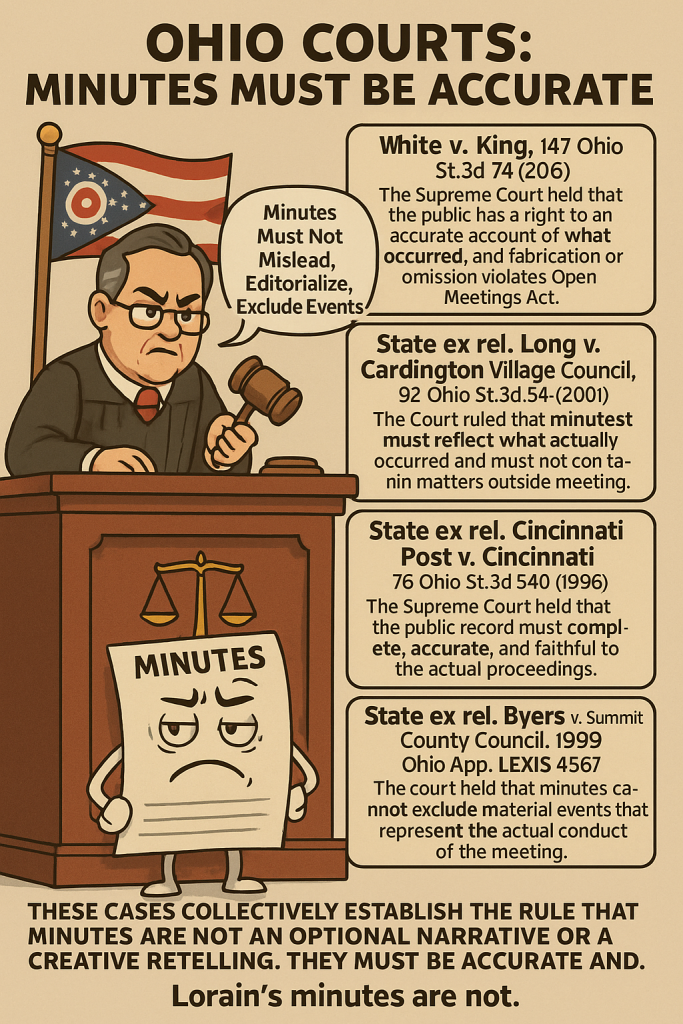

Ohio courts have repeatedly condemned this category of conduct. In White v. King, the Ohio Supreme Court emphasized that public bodies may not circumvent transparency by manipulating the record. In State ex rel. Long v. Cardington Village Council, the Court held that minutes must reflect what actually occurred—not what officials wished had occurred. In Cincinnati Post v. Cincinnati, the Supreme Court made clear that public records must be complete and faithful to the true events. And in State ex rel. Byers and Fairfield Leader, appellate courts held that public bodies cannot omit material events or conceal actions taken by their own members. These aren’t gray areas. These aren’t “guidelines.” These are settled, binding legal standards that define the very nature of a public record.

Lorain’s minutes violate every one of those standards. The omissions are not incidental—they go directly to the heart of the event. They conceal the official’s misconduct. They distort the sequence of actions. They create a misleading narrative that places blame on a citizen who did not speak until spoken to. They do exactly what the Ohio Supreme Court has prohibited: they turn the official record of a public meeting into a curated story that protects power rather than reflects truth.

This is why the integrity of all three recordings matters. They expose the manipulation. They expose the omission. They expose the deliberate rewriting of an official public record. And they expose why this cannot be explained away as a misunderstanding. The only missing voice in the minutes is the voice of the one person who broke the rules. That silence in the record is not natural. It is crafted. And when a public office crafts silence to hide misconduct while amplifying a narrative that harms a citizen, the law steps in. Because the people of Ohio do not grant government permission to edit reality. They grant government the duty to record it.

Why “He Spoke Earlier” Does Not Give the Safety-Service Director Any Right To Address A Citizen Later In The Meeting

There is no rule in Ohio law, no rule in Robert’s Rules of Order, and no local council rule that gives a city official permission to directly address, confront, question, or verbally challenge a citizen during legislative proceedings simply because that citizen spoke earlier during public comment.

Once your public-comment period ended, your legal status returned to the same status as every other person in the chamber: a member of the audience. You no longer held the floor. You had no recognized standing. You were no longer engaged in any procedural segment of the meeting. For that reason, the Safety-Service Director had no right to turn toward you, speak to you, or demand answers from you at all.

City officials do not get to pick individual audience members and initiate dialogue during legislative debate. The only person who may recognize speakers during an active meeting is the presiding officer. A department head holding the floor must direct all remarks to the Council President. This principle is rooted in the basic structure of deliberative assemblies. One person speaks at a time, and all comments are directed through the chair to prevent cross-talk, side conversations, intimidation, or disruptions.

When Director Carrion turned his body, stared directly at you, and repeatedly said “Did you say something” he violated all three foundational rules:

He failed to address the chair.

He initiated a direct exchange with a spectator.

He introduced a back-and-forth that the chair did not authorize.

It does not matter that you were recognized to speak earlier in the evening. Once your remarks were finished, your participation ended. Citizens do not linger in a special category that allows public officials to question or provoke them later. If that were allowed, public comment would become a trap where citizens could be harassed after leaving the podium. Every court that has addressed this issue has emphasized the same point. Officials may not transform legislative debate into targeted confrontations with specific members of the audience.

The case law is unambiguous. In Jones v. Heyman, the federal court held that the public has a right to attend meetings without being targeted or addressed by officials outside of designated participation periods. In Norse v. Santa Cruz, the Ninth Circuit noted that officials cannot manufacture “disruption” by initiating improper exchanges with spectators. In Barna v. Board of School Directors, the Third Circuit held that a citizen’s right to observe legislative proceedings includes the right not to be singled out or addressed individually by officials when they are not holding the floor.

Ohio follows the same principles under the Ohio Open Meetings Act. The public has a right to attend and observe. They do not become participants simply because an official wants to talk to them. When the Safety-Service Director directed comments to you, he was the one who violated protocol. You did not. You answered only in response to an improper address from a city official who should never have been speaking to you in the first place.

The City’s minutes omit his words and preserve only your responses. That is exactly the kind of selective storytelling the law does does not permit. They removed the initiating violation and preserved only the reaction. They erased the public official’s misconduct and framed the citizen as the cause of the disturbance. This is not lawful minute-keeping. It is narrative engineering. It is the fabrication of an official government record. And once done knowingly after being corrected, it becomes a retaliatory act.

You raised constitutional concerns about his building-security directive moments before the exchange. You have a pending federal lawsuit involving that same official. Within minutes of criticizing him publicly, he turned on you, provoked an exchange, and the Clerk then published minutes portraying you as the problem while omitting every word that actually started the confrontation.

This is why your name does not belong in the minutes. You were not a legislator. You were not a participant. You held no portion of the floor. You were a spectator. The only reason your name appears at all is because the City is trying to defend the conduct of one of its own officers by manufacturing justification after the fact.

The law is not on their side. The facts are not on their side. And now the record shows exactly why the minutes must be corrected.

LEGAL SIDEBAR: What the Law Actually Says About Citizen Rights, Council Conduct, and Falsified Minutes

I. Once Public Comment Ends, a Citizen Returns to “Audience Status”

Under the Ohio Open Meetings Act (R.C. 121.22), once public comment closes, the citizen becomes an observer only.

There is no such thing as:

- “lingering speaker status”

- “continuing participation”

- or a rule allowing officials to address a citizen because they spoke earlier.

Nothing in Ohio law, Robert’s Rules, or Lorain’s Rules of Council authorizes a city official to turn toward a citizen and speak to them during deliberations.

Once comment ends, the floor returns solely to the legislative body.

Citizens cannot be questioned, challenged, addressed, or confronted.

II. Only the Presiding Officer May Address a Spectator

Lorain’s Rules of Council follow standard parliamentary law:

All remarks must be addressed to the Chair.

This prevents:

- cross-talk

- intimidation

- side confrontations

- selective targeting

- hostile exchanges with the audience

Directors, department heads, and administrative officials may not speak to citizens in the gallery.

When the Safety-Service Director turned toward a citizen and said, “Did you say something?”, he violated:

- Lorain’s Rules of Council

- Robert’s Rules of Order

- Basic legislative structure

- The citizen’s right to attend without being singled out

III. Federal Case Law: Officials Cannot Target Audience Members

1. Jones v. Heyman, 888 F.2d 1328 (11th Cir. 1989)

Officials may not address or challenge a spectator after public comment. The public has a right to attend without targeted engagement.

2. Norse v. Santa Cruz, 586 F.3d 697 (9th Cir. 2009)

Officials cannot manufacture “disruption” by provoking a citizen. When an official initiates the confrontation, the official—not the citizen—is the disruptor.

3. Barna v. Board of School Directors, 877 F.3d 136 (3d Cir. 2017)

A citizen not recognized by the body is an observer only. Officials cannot single them out, retaliate, or address them directly.

Together, these cases eliminate the notion that “a citizen spoke earlier, so they can be spoken to later.”

That doctrine does not exist anywhere in American law.

IV. Ohio Case Law: Minutes Must Be Accurate—No Exceptions

White v. King, 147 Ohio St.3d 74 (2016)

Minutes must reflect what actually happened.

State ex rel. Long v. Cardington Village Council, 92 Ohio St.3d 54 (2001)

Omitting material facts from minutes is unlawful.

State ex rel. Cincinnati Post v. Cincinnati, 76 Ohio St.3d 540 (1996)

The public has a right to a complete, accurate record.

State ex rel. Byers v. Summit County Council (1999)

Necessary events cannot be excluded to sanitize proceedings.

State ex rel. Fairfield Leader v. Ricketts, 56 Ohio App.3d 97 (1989)

Minutes are not an editorial tool. They may not distort or misrepresent events.

Publishing minutes that erase the official who initiated a confrontation while preserving only the citizen’s reaction is unlawful under every one of these cases.

V. Criminal Liability: Ohio’s Falsification Statute

R.C. 2921.12 – Falsification

It is a crime to knowingly make a false entry in a public record.

If officials:

- remove Carrion’s initiating words,

- omit his actions,

- or present a narrative blaming the citizen instead,

after seeing recordings proving otherwise, the falsification becomes intentional.

This can satisfy the elements of criminal falsification of a public record.

VI. Constitutional Right to Redress Government

Ohio Constitution, Article I, Section 16

“All courts shall be open, and every person… shall have remedy by due course of law.”

A clerk cannot refuse accountability with

“I’m not going to argue with you,”

while performing statutory duties as records custodian.

Citizens have an absolute constitutional right to challenge inaccurate minutes.

VII. Three Independent Recordings Prove the Minutes Are False

The following recordings all match:

- The City of Lorain’s live feed

- Aaron Knapp’s personal body-mic recording

- Garon Petty’s independent recording

All three capture Safety-Service Director Carrion saying:

“Did you say something?”

“Did you say something?”

“Did you say something?”

In all three:

- Carrion initiates the confrontation.

- The citizen does not initiate anything.

- The published minutes contradict the evidence.

When three independent recordings agree and the minutes disagree, the omission is intentional—not accidental.

VIII. Public Comment Earlier Does NOT Create “Open Season” Later

Courts and statutes are consistent:

Officials may only address citizens when the body formally grants the floor.

Not during debate.

Not during motions.

Not during sidebar remarks.

Not because “he spoke earlier.”

Speaking earlier does not forfeit one’s right to be left alone during proceedings.

IX. Why This Sidebar Matters

The law is unambiguous:

- Officials cannot address or target citizens after public comment ends.

- The Chair alone controls recognition.

- Minutes must be accurate.

- Falsification of public records is illegal.

- Retaliation violates the Constitution.

The October 20, 2025 incident violated all of these principles at once.

This is not political.

This is not personal.

This is not subjective.

This is black-letter law.

Case Law: Minutes Must Be Accurate, Not Creative Writing

Ohio courts have repeatedly held that public bodies cannot use minutes to mislead, editorialize, or manufacture a narrative.

White v. King, 147 Ohio St.3d 74 (2016)

The Supreme Court held that the public has a right to an accurate account of what occurred, and fabrication or omission violates the Open Meetings Act.

State ex rel. Long v. Cardington Village Council, 92 Ohio St.3d 54 (2001)

The Court ruled that minutes must reflect what actually occurred and must not contain matters outside the meeting.

State ex rel. Cincinnati Post v. Cincinnati, 76 Ohio St.3d 540 (1996)

The Supreme Court held that the public record must be complete, accurate, and faithful to the actual proceedings.

State ex rel. Byers v. Summit County Council, 1999 Ohio App. LEXIS 4567

The court held that minutes cannot exclude material events that represent the actual conduct of the meeting.

State ex rel. Fairfield Leader v. Ricketts, 56 Ohio App.3d 97 (1989)

A public body cannot include extraneous commentary or misrepresentations in its minutes. They must reflect actions, motions, and factual occurrences only.

These cases collectively establish the rule that minutes are not an optional narrative or a creative retelling. They must be accurate and truthful.

Lorain’s minutes are not.

The Retaliation Problem

Let us be honest. The timing is not an accident. a couple days before this meeting I confronted the city about Director Carrion’s unconstitutional security directive. Just prior earlier the city was served with my pending federal lawsuit naming Carrion, Bradley, Laveck, McCann, and Weitzel in their individual capacities. And when I rose for public comment on the 20th I spoke about that very policy.

The minutes now paint me as the cause of a disruption that their own audio shows was initiated by Carrion himself. In retaliation cases the courts look for three things. Protected activity. Adverse action. Causation. I engaged in protected speech. The minutes impose reputational harm. And the sequence of events speaks for itself.

It is retaliation in the form of a public record.

Why This Matters

This is not about me. It never has been. This is about whether a city government can take the official record of a public meeting, erase the misconduct of one of its own high-ranking officials, and replace it with a narrative that pins the disturbance on a private citizen who did nothing but sit quietly in the audience. This is about whether the most basic tool of democratic accountability, meeting minutes, can be distorted to punish a critic, sanitize an official’s behavior, and create a paper trail that is the opposite of what actually happened.

This is about whether Lorain City Council believes it has the authority to manipulate public records to retaliate against someone who has an active federal civil-rights lawsuit naming several of the very same officials involved. Because when a citizen with a pending lawsuit speaks about unconstitutional conduct, and the official he criticized immediately turns toward him and provokes an exchange, and then the Clerk of Council publishes minutes that erase the official and blame the citizen, that is no longer coincidence. That is retaliation. That is narrative engineering. That is the use of government machinery to target a private person.

This is also about the integrity of the Clerk of Council’s office. She is not merely an employee typing notes. She is the statutory custodian of records under R.C. 149.43 and the Open Meetings Act. Her job is not to protect officials from embarrassment. Her job is not to create a storyline. Her job is to preserve the truth exactly as it occurred. When she knowingly removes a city official’s misconduct from the minutes and knowingly keeps my name, even after being shown the recordings that contradict her version (she wrote and created the fancy fairy tale she printed, TWICE, she is not keeping records. She is crafting fiction. And fiction has no place in the official minutes of a government body.

Minutes are not a script drafted by City Hall. Minutes are not a press release. Minutes are not political armor.

Minutes are the public’s right to know what actually transpired. They are the memory of government. They are the record courts rely on. They are the foundation of transparency.

When minutes become a weapon, democracy becomes a casualty.

The document Lorain published is not a record. It is not an honest account. It is a weapon — pointed directly at a citizen, deployed to rewrite reality, and designed to shift blame away from the official who actually broke the rules.

A public record that knowingly omits material facts is not a mistake. It is falsification. And under R.C. 121.22, R.C. 149.43, and R.C. 2921.12, falsification of public records is not only unlawful — it is actionable.

My lawsuit is coming. The motion for a Temporary Restraining Order will ask the court to immediately halt publication of these false and misleading minutes, compel the City to correct the record, and bar the City from using manipulated minutes as an official account of the meeting.

The City chose this route. I did not. Their decisions put them on the other side of the law, and I will follow that law all the way to its end.

This story is far from over. I will release the full lawsuit, sworn statements, transcripts, synchronized audio comparisons, and the exhibits showing all three recordings capturing Carrion’s words. Every piece of evidence will be public. Every contradiction will be documented. Every act of retaliation will be confronted.

For now the record stands — and the record shows, plainly and unmistakably, that the City of Lorain has crossed a line.

Stay tuned.

From UNPLUGGED with Aaron Knapp

Lawful, not awful.