THE McCANN FILES: PART II

The Evidence the City Tried to Bury

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, LSW, BSSW

Lorain Politics Unplugged — November 2025

When the Evidence Became the Threat

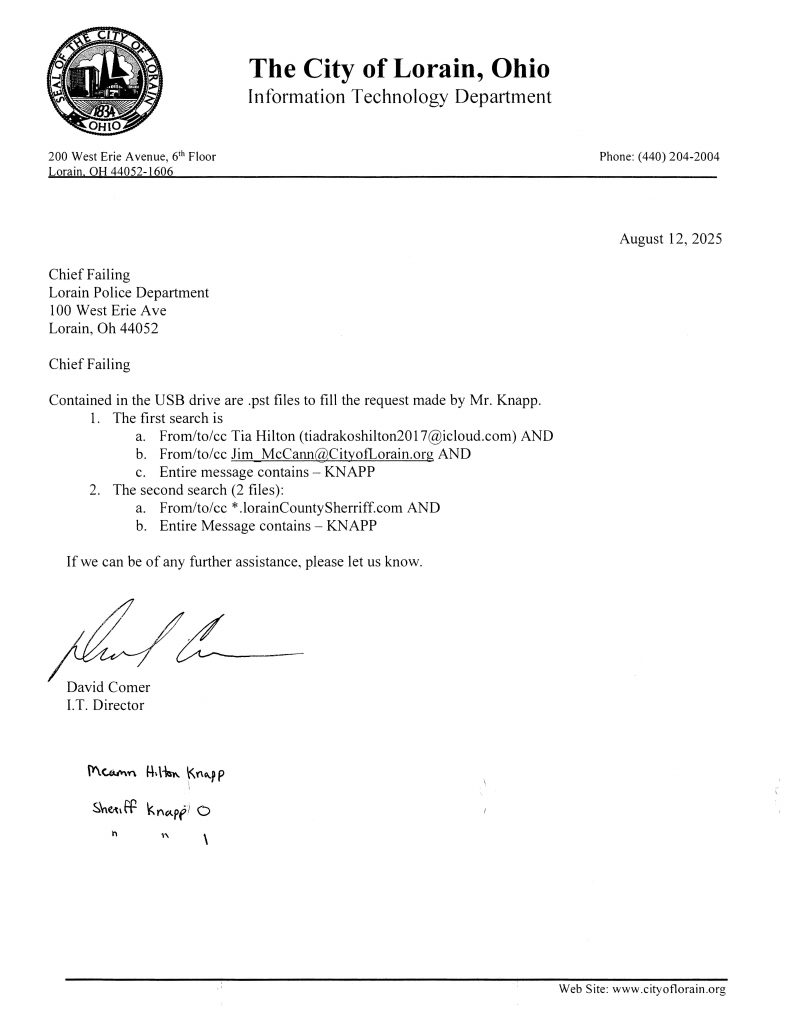

From the moment I submitted the first request for the June 1, 2023 lobby footage, the City of Lorain behaved as though the record itself posed a danger. A simple public-records request should trigger a predictable chain of events: acknowledgment, retrieval, review, and release. Instead, the request slipped into a maze of delays, shifting explanations, and internal hesitation that made one thing unmistakably clear. The City feared what the footage would show because they already knew what it contained. The lobby camera had recorded every moment of the encounter with remarkable clarity. My arrival was uneventful. My tone never changed. My questions were routine. The auxiliary officer was the one stepping in, not me. The lieutenant entered with agitation written into his voice before he even approached. Nothing in the video matched the descriptions that later appeared in the officers’ written accounts. The tape was not neutral to the City’s interests. It contradicted the foundation of every report they produced.

The City understood this from the beginning. That is why the footage became the most protected forty-five minutes of video in Lorain that year. They treated it as a threat because it was the single piece of evidence that could not be reshaped, rephrased, or reframed. Once the video entered the public record, the narrative would no longer belong to the officers, OPS, or the Law Department. It would belong to the camera, and the camera did not lie.

“I asked for the lobby footage repeatedly. Months passed. Policies were cited. Exemptions were invented. The narrative stayed protected.”

How the City Stalled the Footage Until the Chief Left Town

The City’s response to the request revealed the full architecture of obstruction. Instead of allowing the custodian of records to follow the statutory process, the request was quickly rerouted toward Chief James McCann, whose involvement signaled the beginning of the resistance. Conversations inside the department shifted almost immediately toward talking points that had nothing to do with the law. References emerged to camera upgrades, security questions, and internal expectations about how footage should be handled. None of it reflected actual policy. None of it justified withholding a record documenting officer conduct in a public building. Every explanation floated by the City during those weeks had one thing in common: none were grounded in the Ohio Public Records Act.

The lobby video had been produced in other cases without issue. The City had no consistent position, only a consistent outcome. They would not release the June 1 recording while the chief remained in the building. The turning point came only when McCann left town. During that brief window, Captain A. J. Mathewson released the footage without ceremony, without new conditions, and without the obstacles that had been attached to the request for weeks. The moment McCann was not present to direct or influence the process, the record that was supposedly too sensitive, too complex, or too problematic to release became available without difficulty.

“The footage surfaced only when the Chief was gone, and its clarity made the months of silence impossible to justify.”

The footage confirmed everything the City insisted on disputing. It showed precisely the calm, unremarkable interaction I had always described and none of the behavior the officers claimed. It showed the auxiliary officer stepping toward me. It showed Swanger’s entrance and tone. It showed the absence of any escalation on my part. The video aligned perfectly with the truth and not at all with the statements sworn under Garrity. The fact that the footage became available only during the chief’s absence is not a coincidence. It is evidence of internal resistance motivated by knowledge of what the record revealed.

The City’s handling of the footage now plays a central role in the lawsuit because it demonstrates something that written reports alone cannot. It shows that the City knew its story would collapse once independent evidence emerged. The obstruction was not random or procedural. It was purposeful. It reflected a coordinated effort to preserve a narrative already being fed to outside agencies, licensing boards, and administrative offices. The timing, the conduct, and the release of the video only after the chief’s departure all point toward a single conclusion. The footage was not delayed because it was sensitive. It was delayed because it was accurate.

The Credit-Card Knife, the Garrity Contradictions, and the Narrative That Could Not Survive the Facts

The release of the lobby footage did more than contradict the officers’ written statements. It exposed the central flaw in the City’s entire version of events: the officers’ accounts were never meant to withstand scrutiny. They were written with the confidence that no one outside the department would ever see what had actually happened. Once the video emerged, the words on paper and the images on screen diverged so sharply that the contradictions became impossible to explain away.

One of the most striking contradictions involves the auxiliary officer who initiated the first escalation. In his report, he portrayed himself as a compliant, professional gatekeeper responding to an unpredictable citizen. The footage shows the opposite. He is the one stepping forward, tightening the space, and amplifying the tension. And the most revealing detail came not from the video but from the City’s own disciplinary file. Behind the closed doors of City Hall, the same auxiliary officer who implied that I posed a safety threat was quietly reprimanded for carrying a prohibited credit-card knife inside the building that day. The citizen who followed the rules had no weapon. The officer insisting he felt threatened had one concealed in his wallet.

“Every time the officers described the incident, the camera told a different story — and the camera was the only one that wasn’t trying to protect the City.”

This detail was not included in his statement. It appeared nowhere in OPS’s summary. It was never mentioned in the lieutenant’s account. It emerged only later, buried inside the partial discipline that the City hoped would never see daylight. If the goal had been an honest appraisal of the incident, this would have been a central fact. Instead, the City shielded it. They endorsed his narrative, excused his conduct, and minimized the significance of the only concealed weapon present in the lobby that day.

The Garrity inconsistencies run deeper still. Lieutenant Larry Swanger’s statement claimed he entered a “heated argument,” that I was “invading” the auxiliary officer’s space, and that he simply placed a hand on my shoulder to “separate two escalating individuals.” The footage shows a calm lobby. It shows no raised voices from me. It shows no confrontation between two people. It shows the lieutenant stepping into a non-event and injecting emotion into a situation where none existed. His description is not merely inaccurate. It is incompatible with reality. And yet OPS accepted it without resistance, scrutiny, or reconciliation with the video.

The largest contradiction appears in the most consequential part of Swanger’s narrative. In his Garrity statement, he claimed that I had been to City Hall “numerous times,” knew the rules, and behaved like someone familiar with the security process. None of that is true. Before June 1, I had visited City Hall only once, and that was to speak with the Mayor about McCann’s involvement in the Facebook censorship issue. The City later admitted openly that they “mistook me for someone else.” If they mistook me for someone else, then the claimed history never existed. If the history never existed, then the lieutenant’s justification for his threat also never existed. A fabricated justification is not a misunderstanding. It is a falsehood used to rationalize conduct that lacked legal authority.

The contradiction then spread. Lieutenant Tim Thompson repeated a version of Swanger’s claim, asserting that I had allegedly admitted being trespassed from “numerous buildings.” This is not supported by any video, any audio, any document, or any record. It exists solely inside the officers’ reports. Nowhere else. Its presence demonstrates the ease with which misinformation moved within the department and the speed with which unsupported claims became recycled as established fact.

These contradictions did not remain contained within the police division. They traveled. They appeared in supervisory conversations. They shaped OPS’s conclusions. They slid into the Law Department’s language. They echoed inside emails that were forwarded to third parties. They became the foundation for administrative decisions at the Safety-Service Director level and later influenced Mayor Bradley’s responses when confronted directly. What began as a false report became an institutional story, repeated so often that the City began relying on it even after acknowledging privately that its core assumptions were wrong.

This is why the Garrity contradictions matter legally. Courts have long recognized that fabricated evidence or knowingly false statements by police officers violate clearly established constitutional rights. The Sixth Circuit in Gregory v. City of Louisville held that the creation or use of false evidence is independently actionable, regardless of whether a criminal prosecution follows. The moment an officer writes a knowingly false statement and the City adopts it as fact, the constitutional violation begins. Here, that violation did not end with the report. It evolved into a citywide pattern of decision-making built on information the City had every reason to know was inaccurate.

The credit-card knife incident shows how selectively the City evaluated risk. The Garrity contradictions show how carelessly the City adopted fiction as fact. The internal repetition of those contradictions shows how quickly the false narrative became the lens through which I was viewed by agencies across Lorain. None of this happened by chance. It happened because the narrative served a purpose. It insulated the officers. It protected the chief. It provided a justification for treating protected speech as a problem to be managed rather than a right to be respected.

“They wrote reports portraying me as a threat, while quietly reprimanding their own officer for carrying a weapon inside City Hall.”

The story of June 1 was no longer about what occurred in a lobby. It became a script the City recited so consistently that they began governing around it. When a government official’s fiction becomes an institution’s truth, the harm does not stay on paper. It travels wherever the institution allows it to go.

Part Two now turns to the next link in that chain: how the City took those contradictions and weaponized them outside its own walls, into licenses, employment decisions, and investigations that should never have involved the police chief’s personal narrative in the first place.

How a False Police Narrative Escaped the Building and Infected My Career, My Licenses, and Agencies That Had Nothing To Do With City Hall

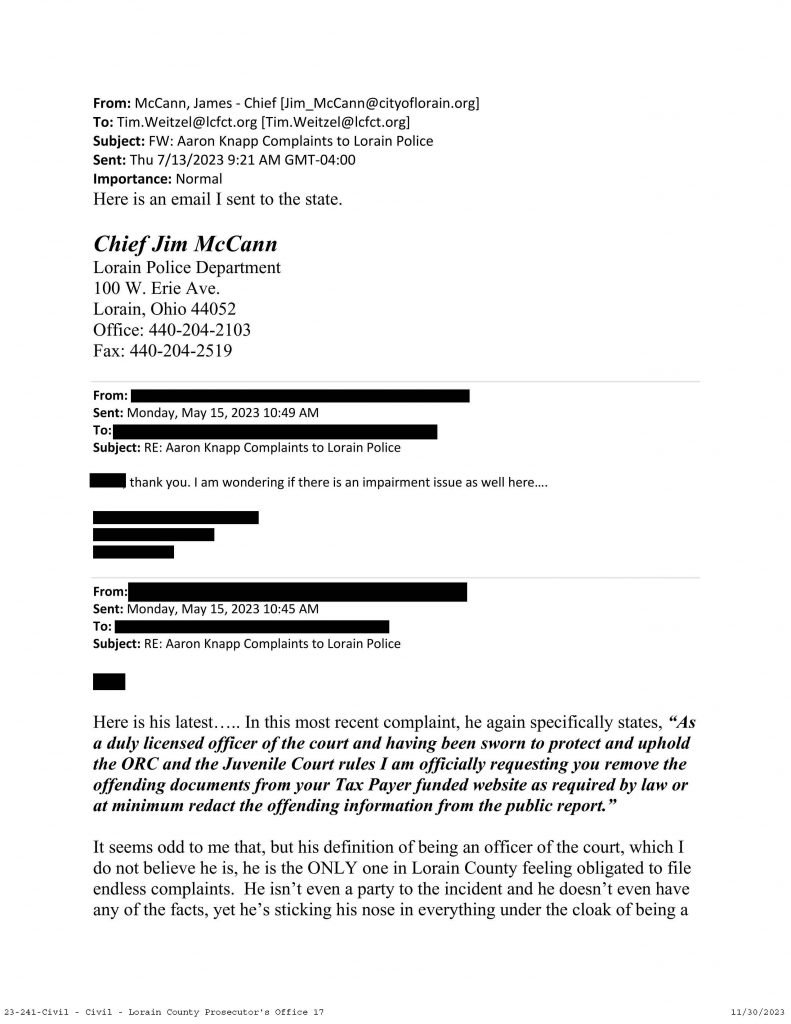

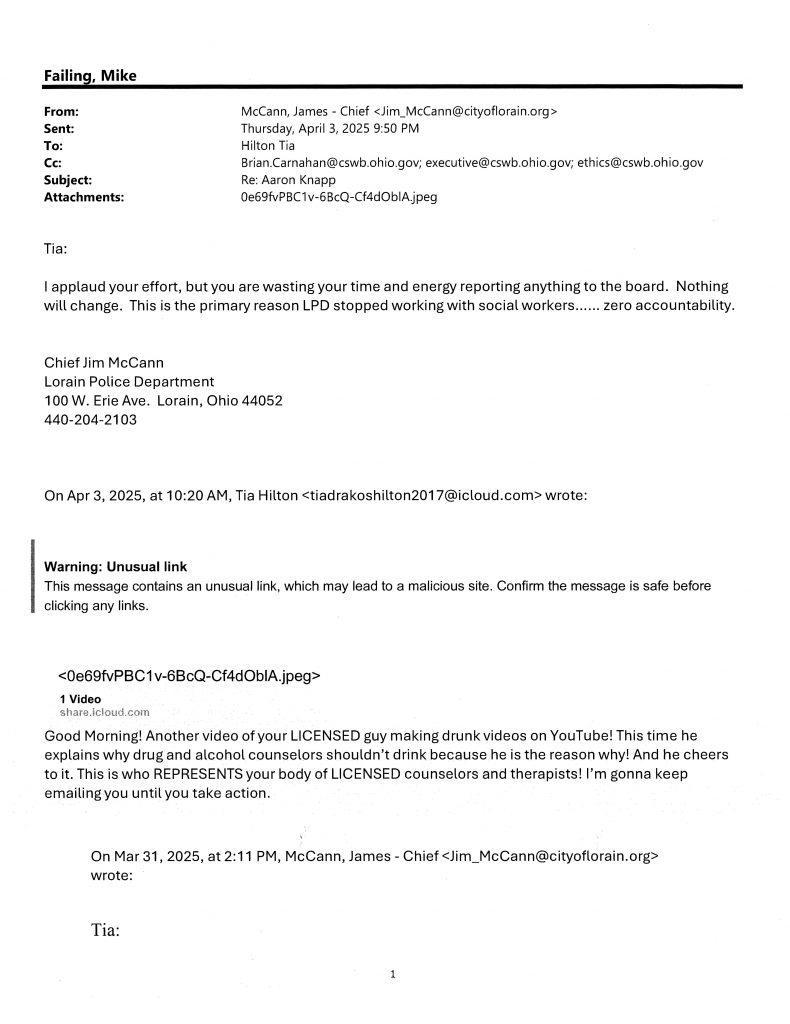

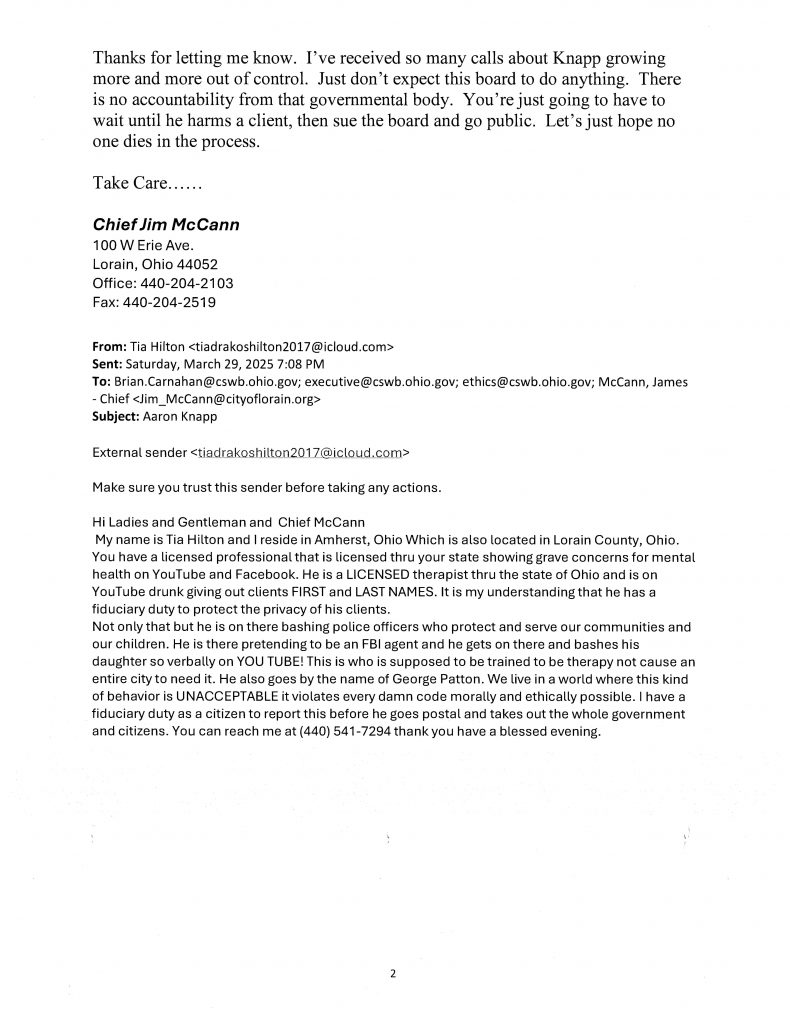

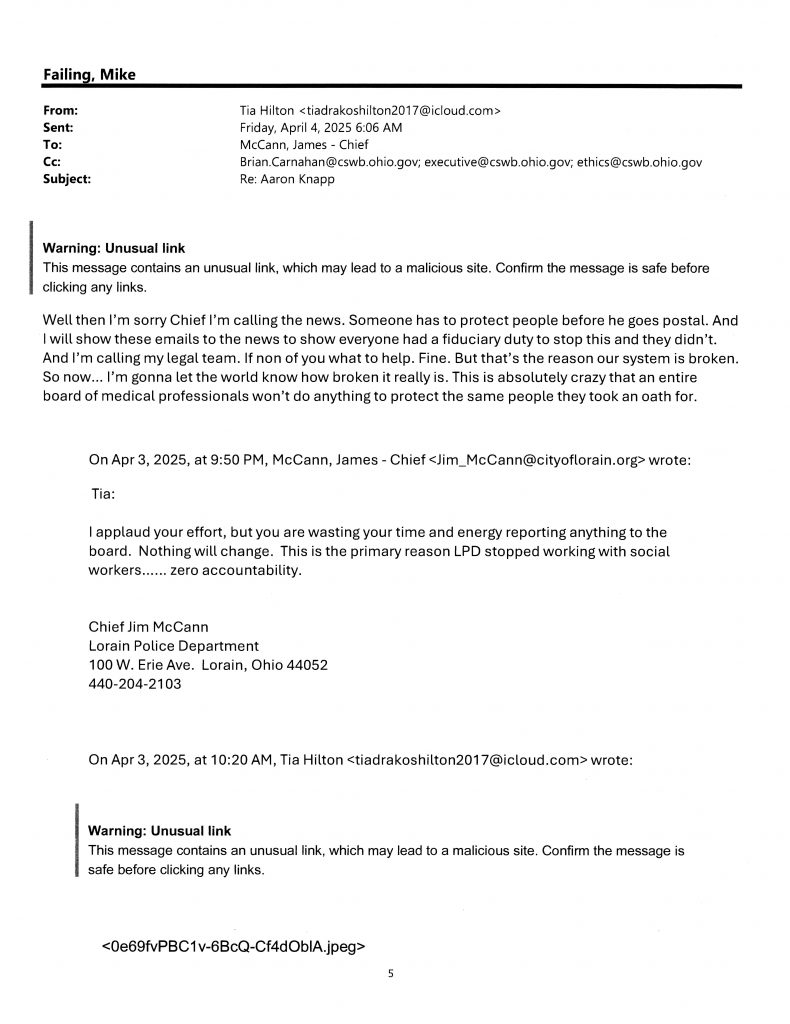

The most revealing part of the June 1, 2023 incident is not what happened inside City Hall. It is what happened after. A false police narrative that should have lived and died within the walls of the Lorain Police Department did not stay put. Once Chief James McCann transmitted his description of me as “unhinged,” the story moved through channels that had no legal or professional reason to receive it. It migrated into administrative offices, circulated into agencies with influence over my work, and eventually reached organizations responsible for evaluating my licensure and employment. A fabricated report became a multi-agency echo, repeated in places where no one had ever filed a complaint against me and where no misconduct had ever occurred.

“When the facts didn’t fit the policy, the City didn’t change the conduct. It changed the policy — four days after the incident.”

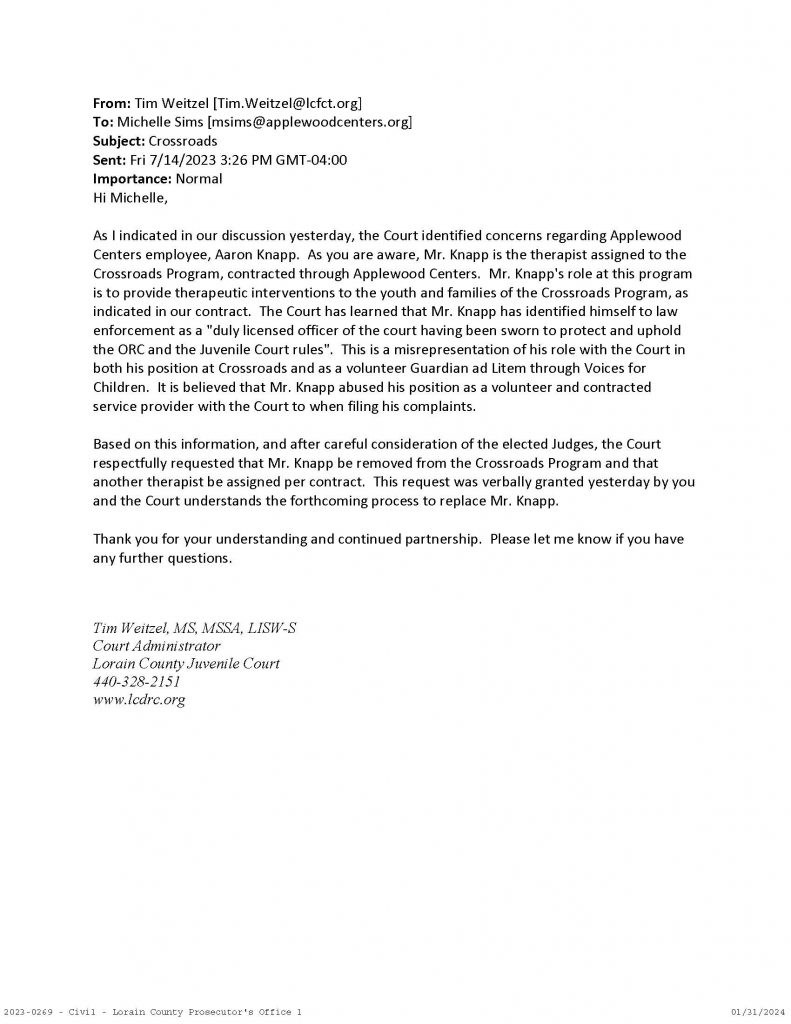

The first person outside the police division to receive McCann’s misinformation was Juvenile Court Administrator Tim Weitzel. His involvement was inappropriate from the moment it began. Weitzel had no authority over City Hall security. He had no investigative role. He was not part of the police chain of command. Yet McCann deliberately forwarded him the narrative that I was “becoming unhinged” and tied that characterization directly to the events of June 1. That message was not informational. It was an attempt to color the perception of someone who held administrative influence over my work as a Guardian ad Litem and someone who maintained relationships across multiple governmental and nonprofit agencies.

Once Weitzel received McCann’s message, the narrative took on a life of its own. Emails later obtained through public records requests show that Weitzel did not merely receive the information. He repeated it. He circulated it. He communicated with outside individuals about concerns that originated entirely from the police department’s false version of events. None of those individuals had ever interacted with me in a way that would justify receiving a warning. Yet they received one anyway, not because of anything I had done, but because the City’s internal narrative portrayed me as a problem to be contained.

The consequences did not remain abstract. My employer, Applewood Centers, began receiving communications influenced by the City’s story, including insinuations that I posed a risk or had engaged in behavior inconsistent with my professional obligations. These insinuations were not rooted in any workplace conduct. They originated from the police chief’s false narrative and the distortions repeated by those who received his emails. The result was a chain of adverse actions that would never have occurred if the City had not weaponized information it knew to be false.

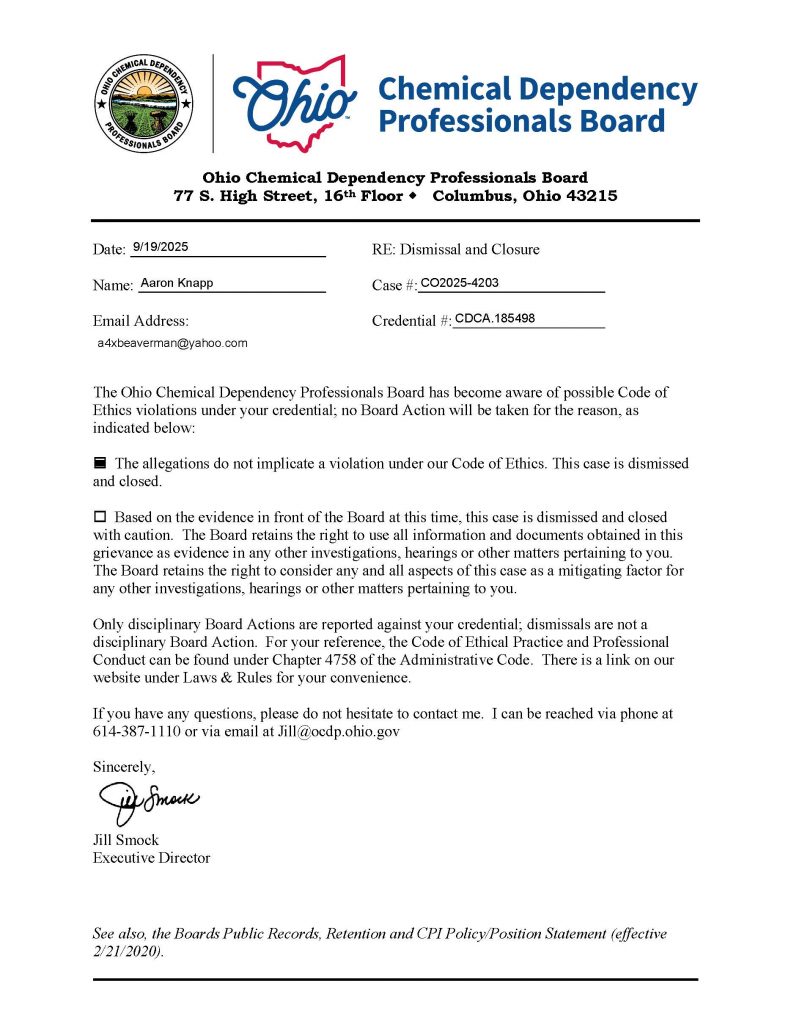

Licensing bodies were then pulled into the gravity of the misinformation. The Ohio Counselor, Social Worker, and Marriage & Family Therapist Board reviewed allegations that mirrored the language of the City’s internal reports. The CDCA Board confronted the same claims. Both agencies dismissed the complaints in full. Their decisions emphasized what the City already knew: none of the allegations had factual grounding. The boards relied on evidence. The City relied on narrative. The disconnect between those approaches exposed the truth. The complaints were not organic. They were manufactured by a system that had adopted the police chief’s misinformation as administrative reality.

The Guardian ad Litem program became another casualty. The program temporarily severed my ability to serve despite a spotless record, no complaints from families, and no substantiated concerns. Once the truth emerged and the links to the City’s false narrative became clear, the GAL program quietly reinstated me. That reinstatement was not a courtesy. It was a correction. It signified that the program recognized the allegations for what they were: the administrative fallout of a retaliatory police narrative rather than a reflection of my professional conduct.

It is important to understand how unusual this chain is. Government officials do not ordinarily share speculative concerns about a private citizen with unrelated agencies. Licensing boards are not typically informed about routine City Hall interactions. Employers do not receive communications about citizens expressing their First Amendment rights. Guardian ad Litem programs do not base determinations on police narratives unrelated to court performance. The only reason these events unfolded in this order is because the City’s narrative acted like a contagion. Once McCann sent the first email, every subsequent recipient behaved as though they had inherited a problem requiring their vigilance.

This is the hallmark of retaliation under federal law. It is not always loud. It is not always declared. It often appears in the form of subtle but coordinated decisions across multiple institutions. Hartman v. Moore teaches that retaliatory harm can occur long before charges are filed. Mt. Healthy clarifies that adverse action is actionable when motivated even partially by protected speech. Nieves explains that the presence of probable cause does not shield retaliatory conduct where the government’s motive is punitive. The pattern that unfolded after June 1 fits precisely into that framework. My criticism of the police department’s unconstitutional Facebook censorship triggered an institutional response designed to discredit and isolate me.

The City’s attempts to distance itself from the fallout do not change the fact that the chain began with its officers and its chief. The further the narrative traveled, the more damage it caused. None of the agencies involved initiated their own concerns. They reacted to information provided by the City. Once they learned the truth, each agency reversed course. The only entity that has not reversed course is the City of Lorain itself.

“It wasn’t confusion. It was containment. The longer the City kept the video out of view, the longer the false narrative stayed intact.”

When a false narrative leaves the confines of a police department and begins shaping the decisions of unrelated agencies, the problem is no longer miscommunication. It is municipal conduct that has breached its legal boundaries and violated constitutional rights. The City did not merely mismanage information. It weaponized it. It exported it. It allowed it to infect systems with the authority to influence my employment, my licenses, and my professional reputation.

Part Two continues next with the structural analysis of how Lorain’s leadership embraced this false narrative, how its administrative branches built policy around it, and how its legal department worked to preserve it long after the evidence disproved it.

How Lorain’s Leadership Adopted the False Narrative and Built Policy Around a Lie

The most revealing transformation in this entire timeline did not occur within the police department. It occurred inside the administrative structure of the City of Lorain. Once the officers’ false narrative was created and repeated internally, city leadership began to reorganize their policies, their communications, and even their building-access procedures to align with a story that the evidence already contradicted. The officers wrote the fiction. But it was the administrative machinery of Lorain that gave that fiction the force of practice.

“The moment the footage was released, the City’s story collapsed. Not piece by piece — but all at once.”

During the June 1 incident, the Safety-Service Director was Sanford Washington. His office had full authority over City Hall operations, including access rules, security expectations, auxiliary staffing, and the protocols governing visitor interactions at the checkpoint. On that day, none of the restrictive policies later claimed by the City existed. There were no appointment requirements. There were no heightened identity protocols. There were no “walk-in exceptions.” Visitors entered City Hall the same way they had for years. That fact is essential, because the City’s own later documentation confirms it.

Four days after the incident, Washington issued a memo dated June 5. In it, he suddenly announced a set of strict access rules, appointment mandates, and identification procedures that bore no resemblance to the practices in place on June 1. The timing makes the purpose undeniable. Washington created policy after the fact to make it appear as though the officers’ actions reflected an established set of expectations rather than a spontaneous escalation sparked by a lieutenant’s frustration and a chief’s animosity toward a citizen who had criticized him publicly.

“What Lorain called ‘security protocol’ was nothing more than retaliation wrapped in procedure.”

The memo did not simply describe new procedures. It retroactively validated conduct that had already occurred. It became the administrative scaffolding that allowed the City to claim that the officers were enforcing long-standing rules. In truth, the rules were created only because the officers’ reports needed them. If the City had possessed these policies before June 1, they would have been posted, referenced, cited in training materials, and reflected in earlier complaints. None of that existed. The policy was written to fit the incident, not the other way around.

When Washington departed and Rey Carrion succeeded him as Safety-Service Director, the same language reappeared. Carrion repeated the post-incident rules in internal meetings and administrative communications, giving the strong impression that a continuous policy existed from one director to the next. This created a veneer of institutional stability around a policy that had actually been born out of a single incident. When Carrion repeated Washington’s language, he did not inherit a legitimate policy. He inherited a narrative created to protect the city from the fallout of the June 1 misconduct.

The Law Department amplified this approach. Instead of providing independent oversight, Assistant Law Director Joseph LaVeck became the interpretive arm of the narrative. Requests for routine records were rerouted to his office. Communications that once flowed through standard custodians were suddenly subject to legal “review” not required under statute. Explanations for redactions or refusals mirrored the same post-hoc justifications that appeared in Washington’s memo. The Law Department did not challenge the police narrative. It formalized it. It translated officer fiction into administrative position.

The Mayor’s office did not correct the misinformation either. When I confronted Mayor Jack Bradley at a Block Watch meeting about the false claim that I had been trespassed from City Hall, he admitted the truth: “We must have mistaken you for someone else.” This acknowledgement undercut the foundation of the officers’ reports and the justification for the lieutenant’s threat. Yet despite knowing this, the City continued to reinforce the same narrative in its communications, its OPS findings, and its Law Department positions. The Mayor’s statement was treated as an inconvenient truth rather than the correction it should have triggered.

This alignment across departments demonstrates how a false narrative becomes institutional. Once the police reports were written, every branch of the City’s leadership acted as though those reports were indisputable. The Safety-Service Director created policy to match them. His successor repeated the same language to preserve them. The Law Department interpreted records law through their lens. The Mayor acknowledged the error but allowed the administrative machinery to continue acting as though the false narrative were true.

“Every official who touched the lobby video made the same choice: protect the narrative, not the truth.”

This is what turns individual misconduct into municipal liability. A city does not become responsible under Monell simply because an officer lies. It becomes responsible when the lie becomes the basis for policy decisions, administrative expectations, or official conduct by leaders whose role is to protect the public, not the narrative. In Lorain, that transformation happened quickly and decisively. The officers wrote the story. But the City adopted it.

The result was predictable. Every part of the administrative response after June 1 reflected the same underlying intent: to preserve the narrative, insulate the officers, and minimize the possibility that the truth would surface. This administrative pattern is now a central part of the federal case, because it establishes not only that the City acted on misinformation, but that it institutionalized it. That is the moment where a false report becomes a municipal custom, and a municipal custom becomes a constitutional violation.

Part Two continues next with the legal threshold the City crossed once its administrative branches acted on the false narrative, how its decisions met every definition of retaliation under federal law, and why the lawsuit now names both the City and the individuals who carried the narrative forward.

When Administrative Fiction Becomes Federal Liability

The false narrative created inside the Lorain Police Department could have remained an isolated problem if the City had corrected it when the evidence surfaced. Instead, the City doubled down. It issued memos based on a policy that did not exist on June 1. It redirected routine records requests through legal channels designed to slow disclosure. It repeated claims that the Mayor himself later admitted were mistaken. And it allowed a police chief’s personal animus toward a citizen to shape the decisions of unrelated agencies. When a city responds to false information not by correcting it but by structuring its operations around it, the problem ceases to be a matter of internal discipline. It becomes a matter of federal constitutional law.

“The footage didn’t just contradict the officers. It exposed the machinery behind the retaliation.”

Under Monell v. Department of Social Services, a city becomes liable when a constitutional violation stems from a policy, practice, or custom. That principle does not require a written ordinance or an official resolution. Courts recognize that a “custom” may be proven through conduct that is so persistent, widespread, and intertwined with administrative decision-making that it acquires the force of law. Lorain crossed that threshold the moment its leadership aligned behind the officers’ false narrative and treated it as the basis for building rules, justifying threats, denying access, and framing a citizen’s credibility across multiple systems.

The June 5 memo issued by Safety-Service Director Sanford Washington is a prime example. The policies described in that memo did not exist on June 1, yet the memo was held out as if it reflected long-standing practice. When the post-incident rules were repeated later by Director Carrion, the City effectively ratified a policy created solely to justify an event that had already occurred. That is not merely poor timing. It is evidence of a municipality attempting to retroactively shape fact with fiction.

The Law Department’s conduct intensified the problem. When records practices change only after a citizen criticizes the police department, the City reveals motive not grounded in policy but in retaliation. Requests that once flowed smoothly suddenly hit bottlenecks. Explanations became more evasive and less consistent. The claim that the lobby was a “court facility,” invoked selectively, contradicted the City’s own disclosure history. The claim that footage exposed security vulnerabilities lacked any factual basis. The insistence on routing records through legal review created delay but not clarity. All of these actions occurred after and only after Chief McCann sent his email calling me “unhinged” and implying that the City should treat me differently.

“When misconduct becomes institutional, policy becomes a shield instead of a safeguard.”

Retaliation under federal law does not require overt punishment. It requires an adverse action that would deter an ordinary citizen from exercising their First Amendment rights. In Hartman v. Moore, the Supreme Court recognized that retaliatory animus can influence government decisions long before charges are filed. In Mt. Healthy City School District v. Doyle, the Court held that adverse employment-related actions taken even partly because of protected speech violate the Constitution. In Nieves v. Bartlett, the Court reaffirmed that retaliatory conduct remains actionable even when the government claims a neutral justification, particularly when the government treats a speaker differently from others.

Lorain’s administrative conduct fits squarely within this framework. After the Facebook censorship dispute, I was treated differently. After I challenged the chief publicly, my requests were handled differently. After the chief imported misinformation into the administrative hierarchy, unrelated agencies reacted as though my presence alone signaled misconduct. The timing is not coincidental. It establishes causation under the retaliation doctrine.

Municipal liability is further supported by the use of false or misleading evidence. The Sixth Circuit’s decision in Gregory v. City of Louisville makes clear that a constitutional violation occurs the moment fabricated evidence is created or relied upon for an adverse action. Here, that adverse action occurred the moment the lieutenant’s Garrity statement was used to justify denying me access to City Hall, threatening arrest, and spreading misinformation through official channels. The City did not simply fail to correct the falsehoods. It operationalized them.

When a city organizes its practices around a false narrative, it signals knowledge and intent. The updated building-access rules, the law department’s obstruction, the OPS endorsement of an account contradicted by video, the Mayor’s acknowledgment that the officers were mistaken, and the City’s refusal to correct the narrative all point toward a single conclusion. Lorain transformed misinformation into policy. Under federal law, once a city acts on a false narrative as if it were true, it owns that narrative and the constitutional consequences that follow.

This is why Knapp v. City of Lorain, 1:25-cv-02213-DAR, names not only the City but the officials who participated in the narrative’s creation, adoption, expansion, and enforcement. The lawsuit is not about a single incident or a single officer’s misstatement. It is about a municipal system that responded to protected speech with institutional force, reshaped policy to match falsehoods, and retaliated through channels far beyond the walls of the police department.

The Cover-Up Becomes the Case: How Lorain Turned a Single Lie Into a Citywide Retaliation Machine

By the time the evidence was assembled, the pattern was unmistakable. What began as a lieutenant’s false claim inside the City Hall lobby became the organizing principle behind a year of decisions made by multiple departments, multiple officials, and multiple agencies. Every part of the City’s structure reacted to the same fictional core, and every reaction created new harm. The City repeated the lie often enough that it became the default explanation for conduct that made no sense on its own. It fueled policy changes. It justified denials. It shaped the OPS conclusions. It drove the misconduct of individuals who had no prior involvement. And eventually, it produced the kind of cumulative constitutional violation that federal courts were built to address.

The cover-up revealed itself in the details. OPS chose to quote the assault statute while ignoring the false trespass threat. The Safety-Service Director chose to issue a memo only after the incident and then describe it as an ongoing expectation. The Law Department chose to frame the lobby footage as a security risk until the chief was unavailable to interfere, at which point the record suddenly became releasable. The Mayor admitted a mistake but did nothing to correct the administrative processes still relying on that mistaken identity. Licensing boards dismissed the City-inspired allegations, yet the City continued distributing the same misinformation to agencies with influence over my work. These choices were not random. They were the predictable byproduct of a system that decided early on that the lie deserved protection and the truth deserved containment.

The City’s behavior also revealed the political dimension behind its actions. In ordinary circumstances, a municipal government corrects its record when the evidence contradicts an officer’s report. It does not issue post-dated policy to protect the officer. It does not reroute its records processes through legal bottlenecks. It does not allow its chief to transmit inflammatory descriptions of a citizen to agencies unrelated to his division. It does not quietly discipline an auxiliary officer for possessing a prohibited knife while publicly defending the same officer’s credibility. These are not the actions of a city focused on accuracy or public safety. They are the actions of a city protecting someone in power.

This is precisely why the federal lawsuit matters. Without litigation, the City’s narrative would have remained intact inside every office where it traveled. The officers’ statements would have remained accepted as truth. The OPS findings would have remained the final word. The post-incident memo would have continued masquerading as established policy. The lobby footage would have remained buried. And the false assertions circulated to agencies beyond the City’s authority would have remained uncorrected, continuing to influence employment decisions, professional determinations, and the credibility assessments of individuals who never witnessed the June 1 encounter.

In federal court, however, the City’s administrative narrative loses its insulation. Evidence overrides hierarchy. Video outweighs rhetoric. Emails receive scrutiny instead of deference. Garrity statements are compared to actual footage. Post-incident policies are examined for what they are rather than what the City claimed them to be. In this setting, the City’s cover-up does not merely look inappropriate. It looks deliberate, coordinated, and retaliatory.

The final component of Section Seven is the most important: the through-line. Every retaliatory action, every false report, every administrative echo, and every obstruction aligns around a single moment. That moment was not the day I walked into City Hall. It was the day I challenged the Lorain Police Department’s unconstitutional censorship of public comments on its Facebook page. The City did not react to my conduct in the lobby. It reacted to my speech about their conduct online.

The retaliation did not begin with a metal detector. It began with a First Amendment question the chief did not want to answer. Everything that followed—the false narrative, the Garrity contradictions, the fake trespass, the OPS endorsement, the post-incident policy, the law department obstruction, the professional fallout, and the administrative repetition—originated from the same cause. A citizen challenged a government official’s misuse of authority, and the official responded with the full weight of the institution.

This is why the final act of Part Two leads directly into Part Three. What Lorain tried hardest to suppress is no longer hidden. The video is real. The narrative is false. The policy was written after the fact. The retaliation is documented. And now, for the first time, the public will see the full internal email chains, the suppressed communications, and the administrative proceedings that tie together every element of the City’s conduct.

Conclusion: The Door That Should Have Stayed Closed

June 1, 2023 was not the basis of my lawsuit, and it is nowhere pleaded as a claim. It did not produce charges, discipline, or any legal action against the City. On paper it looks like a minor dispute, a forgettable lobby encounter, the kind of municipal friction that never leaves the walls of City Hall. And if the City of Lorain had handled it honestly, that is exactly what it would have remained. But the significance of June 1 was never in the moment itself. Its importance lies in what it revealed, what it triggered, and what it exposed about how the City responds when a citizen challenges its authority.

The encounter showed how quickly the truth could be rewritten once it passed through the hands of officers who viewed criticism as hostility rather than accountability. It showed how easily a false claim could transform into an administrative assumption. It showed how swiftly a narrative could expand beyond the officers directly involved and reach officials who had no business receiving it. And it showed how ready the City was to adopt and protect misinformation when doing so served an internal objective. June 1 opened the door, but the City is the one that walked through it.

The real story, and the core of the lawsuit now pending in federal court, lies not in what occurred at the metal detector but in everything that followed. After the City rewrote the events of that day, the same distortions began appearing inside emails, policies, memos, licensing communications, and personnel decisions across 2023, 2024, and 2025. What began as a mischaracterized lobby encounter became the foundation of a retaliatory architecture that took on a life of its own. The officers involved never filed charges. But the City, acting through its highest officials, carried forward the assumptions built on their false statements, using them to justify actions long after the incident was over.

This is where the constitutional dimension enters the story. It was my protected speech about the police department’s unlawful Facebook censorship that preceded the incident. It was that same protected speech that shaped the chief’s attitude before I arrived. And it was the same protected speech that animated the City’s decisions in the months that followed. June 1 mattered because it revealed how the City reacts when that speech challenges its comfort. The retaliation that followed is the reason a lawsuit now exists.

The City did not face a threat. It faced a question about transparency. It answered that question with misinformation, institutional defensiveness, and a chain of decisions that grew increasingly disconnected from the truth. The City escalated the consequences far beyond any interaction that took place in the lobby. The lawsuit is not about the opening act. It is about the pattern it exposed.

Part Two ends here because the next phase of the story no longer concerns speculation, perception, or contradictory accounts. It concerns written records, email chains, internal communications, licensing determinations, personnel decisions, and administrative actions that occurred months and years after June 1. These documents form the spine of what became an escalating pattern of retaliation — not a misunderstanding in a lobby, but a multi-agency reaction to a citizen who insisted that the law applies even when the government finds it inconvenient.

Now we move into the heart of the case: the communications they thought you’d never see, the retaliation they tried to hide behind bureaucratic language, and the timeline the City never expected to answer for in federal court.

Author Information

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, LSW, BSSW, Community Advocate

Investigative writer, public records advocate, and founder of Lorain Politics Unplugged.

Substack: @LorainPolitics

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

For tips, documents, or story leads: a4xbeaverman@yahoo.com

1 thought on “THE McCANN FILES: PART II”