The Collapse Engineered by Loyalty: How James Burge’s Disciplinary Letter Unraveled Lorain County’s Prosecutor’s Office

Not the romance, not the rumor mill—what ended JD Tomlinson’s career was the disciplinary letter written by the one man he trusted most.

May 12, 2025

Byline:

By Aaron Knapp with Melody Andrich

Investigative Reporters, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

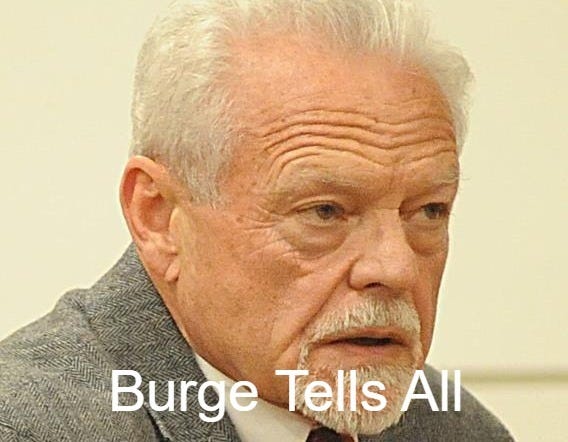

I. Unpacking the James M. Burge Deposition

On February 14, 2025, Attorney Jonathan Rosenbaum, representing his client James V. Barilla, deposed former Judge and former Chief of Staff to Lorain County Prosecutor JD Tomlinson—James M. Burge. In sworn testimony, Burge stated he had been licensed to practice law in the State of Ohio for “a little over 49 years.”

Rosenbaum’s deposition quickly laid bare a political time bomb. Burge, once a Lorain County Common Pleas Court judge, had been criminally convicted and suspended from practicing law in 2019 for falsifying financial disclosures, assigning paid legal work to attorneys who rented space from him, and other abuses of office. Despite that legacy, he was welcomed back into power in 2021 as Tomlinson’s most trusted adviser.

A 2014 indictment had charged Burge with 12 counts. By 2015, he was convicted on three misdemeanors and three felonies—later reduced to misdemeanors by a visiting judge. He resigned and paid a $3,000 fine. In 2018, the Ohio Office of Disciplinary Counsel filed formal charges, resulting in a one-year law license suspension, with six months stayed.

This is the man Tomlinson brought back to serve as Chief of Staff.

Rosenbaum established during questioning that Burge knew early on about Tomlinson’s romantic relationship with Public Outreach Coordinator Jennifer Battistelli. “There were several of us sitting in Mr. Tomlinson’s office,” Burge testified. “They indicated that they were an item, they were boyfriend and girlfriend.” He placed that awareness in either 2020 or 2021—and confirmed Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord also knew.

Petticord’s deposition corroborates Burge’s timeline. He testified he learned of the relationship “sometime in the summer of ’21,” and that Battistelli described it as “on again, off again” over the years.

In her own July 2024 statement, Battistelli said she met Tomlinson through friends in 2000, volunteered for his failed 2016 Prosecutor campaign, and again in 2020 when he won the Democratic nomination over Dennis Will and later defeated Republican Robert Gargasz.

But Burge’s testimony revealed more than just timelines. He admitted to playing an active role in protecting the relationship and managing office fallout. “I was trying to protect the office,” he said. His involvement included suppressing public records, attempting to reframe internal complaints, and shielding Tomlinson from scrutiny.

Burge’s return to power after a criminal conviction—and his central role in shaping office discipline, personnel oversight, and legal defense strategies—reflects a deep rot within Lorain County government. His presence was not incidental; it was structural. He wasn’t just aiding the cover-up—he was architecting it.

What the deposition made clear was this: Burge’s reinstatement as Chief of Staff gave him more influence than he had on the bench—and far less accountability. His knowledge of the Tomlinson-Battistelli relationship, and his eventual decision to discipline Battistelli, would become the fulcrum around which the entire scandal turned.

II. James Burge Enters the Picture

Jennifer Battistelli testifies that incoming Prosecutor Tomlinson would not be keeping two women employed by his predecessor in his newly structured office. Tomlinson had planned to offer the job of public outreach coordinator to his close confidante in his successful 2020 run for Lorain County Prosecutor, Harry Williamson. After a conversation with Tom Williams in December 2020, Williamson declined Tomlinson’s offer and chose to work for Lorain County 911. It was then Battistelli disclosed “that position came open and I talked to Burge about it and well, you can have this position.”

Romance blossoms at the Prosecutor’s Office in May 2021 according to Ms. Battistelli. She testified that the two were together all the time and informed Dan Petticord that they were dating. Battistelli recalls that Dan Petticord said it was OK. “And then came back a couple of months later and said, no, you guys are not allowed to date, and it became a thing basically.” The dye was cast by then, when asked in her interview if she loved him, JD Tomlinson, Battistelli respond’s “Of course, sure, yeah.”

On September 3rd, 2024, JD Tomlinson is deposed by attorney Rosenbaum. In Tomlinson’s sworn testimony, he affirms that Jennifer Battistelli reported to his Chief of Staff, James Burge. Tomlinson also says that Ms. Battistelli was given a raise January 30th, 2023, by Burge. When Rosenbaum further presses Tomlinson on if the Chief of Staff has the authority to grant raises to employees who deserve them, Tomlinson replies “No, those would typically go through me.” Tomlinson changed who Ms. Battistelli reported to due to “some reorganization going along in the office.” Tomlinson refers to creating some efficiencies and less confusion in the divisions as the reasoning for the change of Ms. Battistelli direct superior. One can’t help but refer to Asst. County Prosecutor Dan Petticord’s waffling back and forth with Ms. Battistelli on the relationship between the elected Prosecutor and his subordinate to create some distance between the lovers in the workplace hierarchy.

In reality, the “reorganization” served a dual function: it insulated Tomlinson from direct supervision over his romantic partner while allowing him to retain influence over her position and salary. As Burge later admitted, he gave Battistelli a raise because “she was doing a good job,” yet Tomlinson testified he didn’t authorize it. That contradiction alone speaks volumes about the lack of internal oversight and the informal power dynamics at play.

More troubling, Burge’s return to high-level decision-making included overseeing HR complaints—despite his prior judicial sanctions. His fingerprints were on every personnel shift, particularly those that affected people aligned with or in conflict with Battistelli. This power enabled him to maneuver both promotions and punishments, often without transparency or formal review.

Petticord’s initial approval of the relationship, followed by his reversal, reveals not a principled concern but political calculation. He didn’t act because the relationship created a legal problem—he acted once it became a political risk. “At first, he said it was fine,” Battistelli stated. “Then a few months later he said it wasn’t.” This selective enforcement of ethics speaks to the deeper culture of conditional accountability.

There’s also the question of why Williamson declined the job initially promised to him. Sources suggest he may have sensed that the workplace was already marred by internal favoritism and tension. If so, Williamson’s quiet exit was a red flag ignored by everyone else. Into the vacuum stepped Burge—again.

From a broader lens, Tomlinson’s decision to install Burge as gatekeeper after his disgraceful exit from the judiciary demonstrates a complete disregard for public trust. The position of Chief of Staff should be one of impartiality and ethical rigor. Instead, it became a post-retirement redemption tour for a man who’d already betrayed the public once.

Thus, the picture becomes clearer: Tomlinson created a political inner circle defined by loyalty over law, optics over ethics, and secrecy over accountability. Battistelli was pulled into that vortex—not just as an employee, not just as a partner, but ultimately as the scapegoat when their web of relationships began to unravel.

The institutional structure they built together—Tomlinson, Burge, and Petticord—was engineered not for justice, but for control. And that structure would soon begin to collapse under the weight of its contradictions.

III. Rosenbaum Public Records Request Sheds Light on Resendez’s Actions

The documents obtained in the Barilla vs. Tomlinson public records request shine a glaring, and noticeable spotlight on the crumbling of a secret known to most in the inner circles of Lorain County politics. Sources disclosed that in early 2021, JD Tomlinson had a personal relationship with his employee Jennifer Battistelli. Reports included seeing the pair together at nearly all Tomlinson’s public events, with Battistelli never more than three paces behind him. During her interview, Ms. Battistelli recalls “JD would not leave me alone one day and he gets obsessive and he calls me 100 times, and called me until 4 o’clock in the morning.”

In the sworn testimony by the former Chief of Staff James Burge he thought that the lovers liked each other and if it led to something, she would have to leave the office. Burge would become involved in their quarrels and often engaged in conversation with Tomlinson who he said was “just trying to manage the relationship and still fulfill his duties as the prosecutor.” Burge testified he would speak to Tomlinson about the subject matter Ms. Battistelli and Tomlinson argued about. Battistelli would “often take part of some of our employees who were trying to pursue a promotion or make a lateral change in the office to something that they would enjoy more.” When asked by Rosenbaum, Burge confirmed that Tomlinson and Ms. Battistelli fought about Tomlinson seeing other women.

On July 27th, 2023, Garrett Longacre filed a complaint against Jennifer Battistelli to his Department Head Richard Resendez. Listed as the nature of the complaint was “making or publishing of false, vicious or malicious statements concerning employees (Group II #9).” The statement of facts written are that “Battistelli made a verbal complaint to Chief Petticord (civil) alleging discrimination by Longacre against [redacted].” A follow-up by Burge and Resendez revealed that [redacted] never alleged discrimination.”

Names of any witnesses [redacted] and finally relief requested by Longacre was “WRITTEN REPRIMAND” in all capital letters. The Department Head/Date Received recorded the complaint on August 8th, 2023, and August 11th, 2023, as Richard Resendez.

The public record of the investigation by Richard Resendez reveals that Ms. Battistelli went to Dan Petticord and shared her concerns. When Longacre was informed by Petticord of the concerns lodged by Ms. Battistelli, Longacre decides to file a formal complaint against her. Petticord, seemingly playing both sides, “stated that he did not believe Longacre had discriminated against [redacted]. Later in the day, the report by Resendez states “Longacre met with Tomlinson and expressed concern about the complaint of discrimination against [redacted].” Tomlinson stated he did not believe it and would speak to Ms. Battistelli. The report by Resendez details a heated argument, reported by Longacre, between Longacre and Ms. Battistelli on July 27th, 2023.

On August 2nd, 2023, Chief of Staff James Burge is informed by Longacre and Resendez their concerns about the allegation of discrimination by Ms. Battistelli toward Garret Longacre. The men make their case to Burge and request an investigation if warranted. Longacre is insistent that [redacted] did not make a complaint, and he wanted to know why Ms. Battistelli made a false complaint.

This moment becomes a turning point in the internal drama. It marks the shift from quiet conflict to full-blown office warfare, with Resendez and Longacre escalating the matter through formal HR channels, and Burge beginning to act with force. The fact that Resendez sided so quickly with Longacre—despite no corroborated claim from the third party allegedly discriminated against—raises serious questions about the motives behind the complaint.

What’s more, this dispute wasn’t handled in isolation. It was processed in the same informal power vacuum that defined the rest of the office structure. Petticord, despite being the initial recipient of Battistelli’s concerns, stepped back and allowed others to frame the narrative. As usual, Petticord played both sides, distancing himself from Battistelli just when she needed procedural protection.

Behind the scenes, Battistelli’s advocacy for female and minority coworkers had made her unpopular with some men in the office. Burge even admitted in his deposition that she “advocated for Puerto Ricans,” and that this created tension with Tomlinson. Rather than mediate the cultural and political divides inside the workplace, the leadership chose the easier route: isolate the woman they considered difficult.

It’s no surprise then that the response to Battistelli’s alleged misconduct was immediate and forceful, while no similar urgency was shown when she first raised concerns about discrimination. This double standard permeates every facet of the investigation. If anything, the evidence shows that her advocacy triggered the backlash—not any actual misconduct.

As the dominoes begin to fall, the key actors—Burge, Resendez, Petticord, and Tomlinson—position themselves to protect one another. Meanwhile, the complaint process becomes less about accountability and more about leverage. It’s the classic institutional trick: convert the whistleblower into the problem. In this case, it worked with chilling efficiency, by Longacre and Resendez their concerns about the allegation of discrimination by Ms. Battistelli toward Garret Longacre. The men make their case to Burge and request an investigation if warranted. Longacre is insistent that [redacted] did not make a complaint, and he wanted to know why Ms. Battistelli made a false complaint.

IV. Chief of Staff James Burge Acts, and the Office Begins to Crumble

In a letter dated August 11th, 2023, Chief of Staff James Burge writes his opinion and recommendation to JD Tomlinson regarding the Longacre complaint against Jennifer Battistelli.

The conclusion of the document written by Burge states “Based upon my review of this matter, I find that the miscommunication between [redacted] and Battistelli resulted in Battistelli making a statement regarding Longacre’s management of [redacted] that was untrue. I further find that Battistelli’s subsequent conversation with Petticord regarding Longacre was inappropriate and contrary to office policy. Battistelli has been instructed and cautioned.”

On the same day, Jennifer Battistelli wrote correspondence to James Burge. Ms. Battistelli concludes at the end of her statement that [redacted] “was saying is that she felt she was being treated differently from the other advocates.” “When I was talking to Dan Petticord, if I said the word ‘discrimination’ it was not the right word.”

Ms. Battistelli spoke up for what she thought may have been mistreatment of a fellow female employee. Burge said in his deposition referring to Battistelli, “if the people she liked weren’t in the mix, she would argue with JD about that.” Burge went on to say, “She is Puerto Rican and she would advocate for Puerto Ricans and sometimes they weren’t exactly what we were looking for and they would argue about it.” This kind of characterization reduces her advocacy to favoritism and dismisses legitimate concerns about equity and representation.

Burge’s report to Tomlinson was not an impartial finding—it was the culmination of a calculated effort to discredit Battistelli. There was no formal hearing. No second review. Just Burge deciding, on his own terms, that the complaint against her was valid while her concerns about discrimination were invalid. This unilateral handling of sensitive personnel disputes raises serious due process concerns and reflects a culture of top-down retaliation.

By August 15th, Battistelli met with Tomlinson to express her concern about the handling of the situation. This was no ordinary workplace meeting. According to her EEOC complaint, that encounter escalated to physical violence.

“Tomlinson yelled at me, grabbed me, and shook me, leaving injuries and bruises,” she wrote. “I immediately left the office and resigned my position.”

The fact that this occurred only four days after Burge’s memo indicates that the administrative retaliation quickly bled into personal confrontation.

At this point, it becomes impossible to separate personal bias from procedural failure. Battistelli wasn’t just an employee under scrutiny—she was the Prosecutor’s girlfriend, being disciplined by his Chief of Staff, following a complaint instigated by a male coworker who felt slighted. And the internal chain of authority—Tomlinson, Burge, Petticord—all aligned to silence her rather than solve the problem.

Burge’s subsequent justification for disciplining Battistelli reveals a deep paternalistic instinct. “She had been cautioned,” he insisted. But what was she being punished for, really? Speaking up for a colleague? Questioning internal dynamics? Or simply refusing to play the silent role expected of her?

The paper trail shows a clear sequence: Battistelli raises concerns → Petticord waffles → Longacre files complaint → Resendez validates it → Burge punishes her → Tomlinson allegedly assaults her → she resigns. That is not a coincidence. That is a chain of retaliation disguised as administrative policy.

In most workplaces, this kind of conduct would trigger an independent investigation. In Lorain County, it triggered a cover-up. Burge never consulted an outside HR professional. No one was put on leave pending inquiry. Instead, the leadership doubled down, choosing loyalty over legality.

This section of the timeline is crucial. It demonstrates how quickly an office built on personal loyalty and unchecked power can implode when faced with internal accountability. Rather than pause and reassess, Tomlinson and Burge hit the gas—and drove the office into scandal.

V. The Hidden Hands: The Withholding of the EEOC Complaint

The full deposition of James Burge reveals that he, Dan Petticord, and J.D. Tomlinson collectively made the decision to withhold Jennifer Battistelli’s EEOC complaint from public release, even after multiple formal public records requests had been submitted. Despite acknowledging the complaint was a government record, Burge stated that they feared political damage and legal liability. “If we were to produce this pursuant to a public record’’ request,” Burge testified, “Tomlinson would have exposure for libel.”

The complaint in question included allegations that Battistelli had been retaliated against and assaulted after reporting discrimination. Burge claimed some statements in the complaint were false, pointing specifically to Garrett Longacre allegedly calling a colleague “ghetto,” which Longacre denied. Still, they never sought an independent review. Instead, they played judge, jury, and gatekeeper to the truth.

Rather than submit the $100,000 settlement claim to the county’s insurer, CORSA, Petticord and Burge pushed it through as a requisition—sidestepping the normal resolution process. This maneuver denied the public and the commissioners a chance to debate or vet the payment. “We never intended to pay a cent or even negotiate on Claim 1,” Burge admitted, referring to the sexual harassment and assault allegations.

Burge also admitted he selectively disclosed only parts of the EEOC complaint to certain commissioners. He stated he informed Dave Moore and Jeff Riddell about Claim 2 involving racial discrimination but deliberately omitted Claim 1. “They’re friends of mine,” Burge explained. “We relied upon the advice of counsel for that.” The intent, clearly, was to manage fallout—not accountability.

Time pressure further influenced the decision. According to Burge, Petticord received the EEOC complaint via email on October 10, 2023. By the next morning, Burge had reviewed it. He testified: “Dan got it on the 10th… I saw it on the 11th on his phone.” Soon after, the payout was pushed through. “She wanted her money,” Burge said of Battistelli. Jack Moran, her attorney, was reportedly pushing for a rapid resolution.

When asked why the document was withheld despite legal obligations, Burge admitted: “Because of the false and defamatory nature of it… under the law, it was not a public record subject to production.” Yet the court would later rule the opposite, ordering the EEOC complaints release, exposing the unlawful suppression of a public record.

The rationale for suppressing the document was, in Burge’s words, to avoid “political embarrassment.” When asked if releasing the document would have hurt Tomlinson politically, Burge responded, “It would depend on how we managed it.” Ultimately, he conceded: “It probably would have been a better move to tell Moran bring it and defend it.”

In the same testimony, Burge confirmed that the statement used to justify withholding was never shown to the commissioners. The response by Eric Xamba, the paralegal tasked with denying the public record, was allegedly reviewed by Petticord. “Ultimately, the decision lies with the commissioners,” Burge admitted, “but it’s hard to imagine them not taking advice from the Prosecutor’s office.”

This wasn’t just a misstep. It was a deliberate concealment of a credible discrimination and assault complaint by public officials, using the county’s legal machinery to shield themselves and shut down inquiry. And it was a strategy agreed upon by Burge, Petticord, and Tomlinson—three men protecting each other instead of serving the public.

The broader implication is chilling: if a credible claim involving workplace assault and racial discrimination can be buried under the pretense of libel and “friendly discretion,” then Lorain County’s promise of transparency is meaningless.

VI. Coercion and Control: “Sign This So We Can Bury It”

Perhaps the most disturbing part of James Burge’s deposition is the window it provides into the tactics used to silence Jennifer Battistelli after she dared to challenge the power structure. In his sworn testimony, Burge admits he personally wrote a statement—by hand—intended for Battistelli to adopt, rewrite, and sign. This document would have served as a retraction of her claims, downplaying her concerns about workplace discrimination to a mere “miscommunication.”

“This was a document that I wanted to give Jennifer a chance to explain herself,” Burge testified. “I think I did—she acknowledged that moving or not having Lisa in the victim advocate office at that time did not arise from her ethnicity.” But when pressed, he conceded that Battistelli never signed it. “I never did [receive it],” he admitted.

Instead of dropping the issue, Burge pivoted. He unilaterally issued a report that mirrored the unsent statement and submitted it as the official conclusion to the Longacre complaint. “Had she adopted and signed that statement, it would end the investigation,” Burge admitted. But she didn’t, and yet the investigation was still marked as resolved in Tomlinson’s favor.

Burge’s tactics didn’t stop there. In follow-up emails and text messages, he urged Battistelli to affirm the EEOC complaint was false. One message read, “I wanted her to agree that she was not a whore on salary and benefits… because that was false.” The level of misogyny is jaw-dropping—and it came from a former judge tasked with investigating misconduct.

In another communication marked as Exhibit 18, Burge explained to Battistelli that if she admitted the EEOC complaint was false, the county could avoid releasing it: “The Prosecutor’s office can resist publication… on the grounds that it’s false and defamatory.” This was not legal advice—it was strategic manipulation to protect reputations.

Asked by Rosenbaum if he believed the complaint’s defamatory claims disqualified it from being a public record, Burge said yes, relying on unnamed legal memos. But the court later ruled otherwise. The complaint was a public record. The suppression was unlawful.

The underlying goal was clear: retroactively reframe the narrative. Burge, Petticord, and Tomlinson had no interest in investigating the complaint in good faith. Their concern was damage control. As Burge stated bluntly in his deposition, “We never intended to pay a cent or even negotiate on Claim 1.” Yet the payout still happened—quickly, quietly, and with every attempt to make it disappear.

Burge’s belief that he could define the truth for Battistelli—force her to recant, rewrite her trauma, and deny what happened—is emblematic of a broken justice system. “I was hoping that if she acknowledged that,” he said, “then I wouldn’t have to take any other action.” Translation: sign this and shut up.

The fact that she refused to sign anything, despite being pushed by the most powerful men in the office, is telling. Battistelli stood her ground, and for that, she was targeted, discredited, and ultimately forced out. It’s textbook retaliation dressed up in bureaucratic procedure.

What Burge, Petticord, and Tomlinson did wasn’t just unethical. It was a concerted effort to rewrite the official record, deny the public transparency, and silence a woman whose only mistake was believing the system might protect her.

VII. The Resendez Reversal: Public Denial vs. Documented Involvement

Editor’s Note: While much attention has focused on the romantic relationship at the center of this case, the actual collapse of JD Tomlinson’s administration began the moment James Burge, his longtime mentor and Chief of Staff, filed the formal discipline letter against Jennifer Battistelli. That action—trusted, personal, and procedural—set the entire chain reaction into motion.

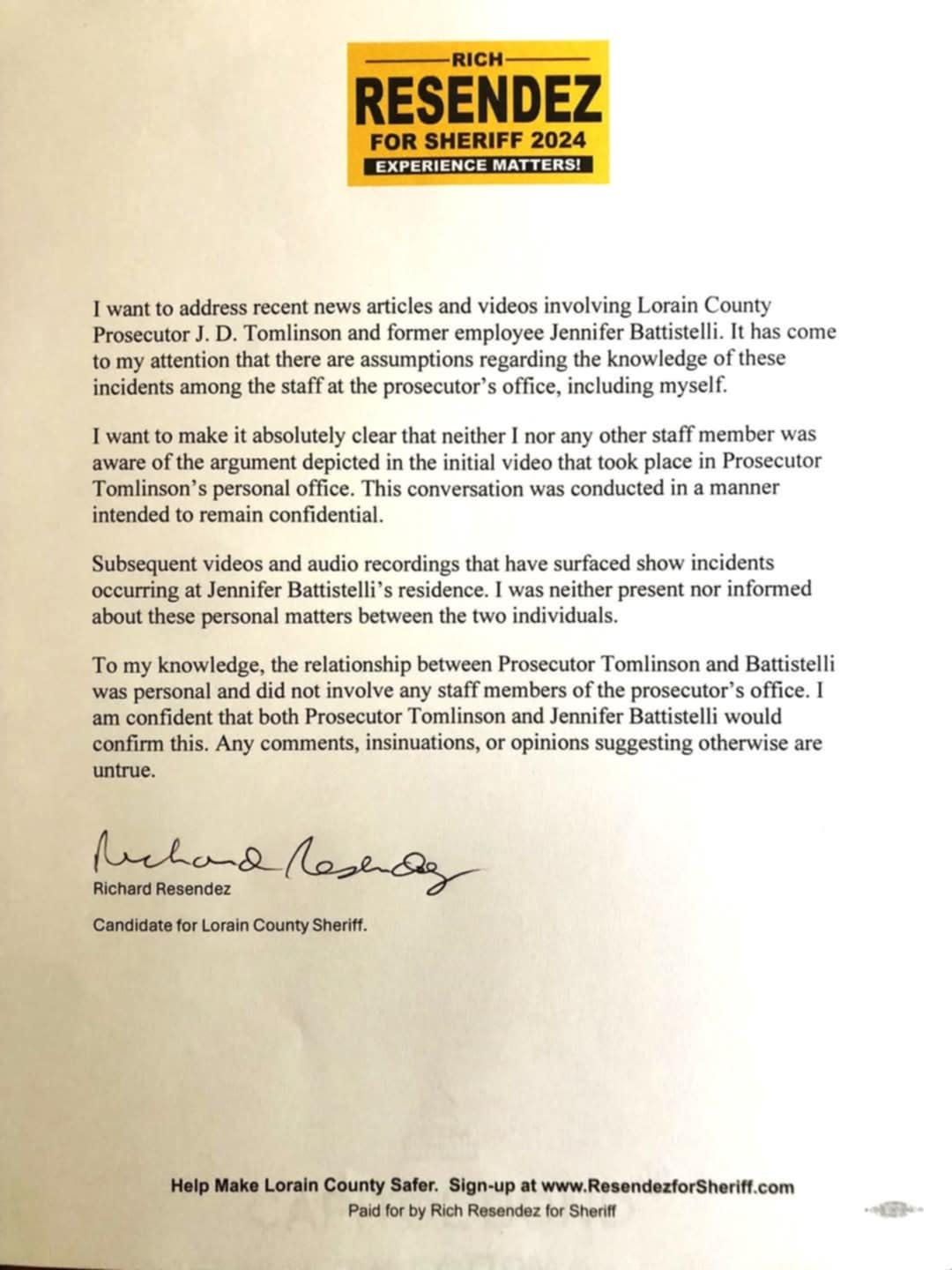

As the Tomlinson-Battistelli scandal unraveled publicly, one figure attempted to distance himself from the fallout: then-Chief Investigator and 2024 sheriff candidate Richard Resendez. In a campaign statement issued under his official logo, Resendez denied having any prior knowledge of the internal conflict between JD Tomlinson and Jennifer Battistelli. “Neither I nor any other staff member was aware of the argument depicted in the initial video,” the statement read. He further insisted that the romantic relationship “was personal and did not involve any staff members of the prosecutor’s office.”

However, official documents and internal emails tell a different story. On August 8 and 11, 2023, Resendez received and signed off on a written complaint by Garrett Longacre against Battistelli. Resendez also participated in the investigation process, communicating with both Longacre and Burge regarding the claims. The fact that his name appears on the official documentation contradicts his public denial months later.

The contradiction deepens when one considers the content of Resendez’s own investigation. He confirmed in internal notes that he and Burge discussed the substance of the complaint and concluded that Battistelli’s actions warranted an administrative response. At no point during that process did Resendez distance himself or signal a lack of awareness. Instead, he was a facilitator.

In fact, James Burge confirmed in his sworn deposition that Resendez was the department head who received and processed the complaint against Battistelli. “Rich Resendez and Garrett Longacre brought the matter to me,” Burge testified, underscoring the inconsistency with Resendez’s campaign narrative.

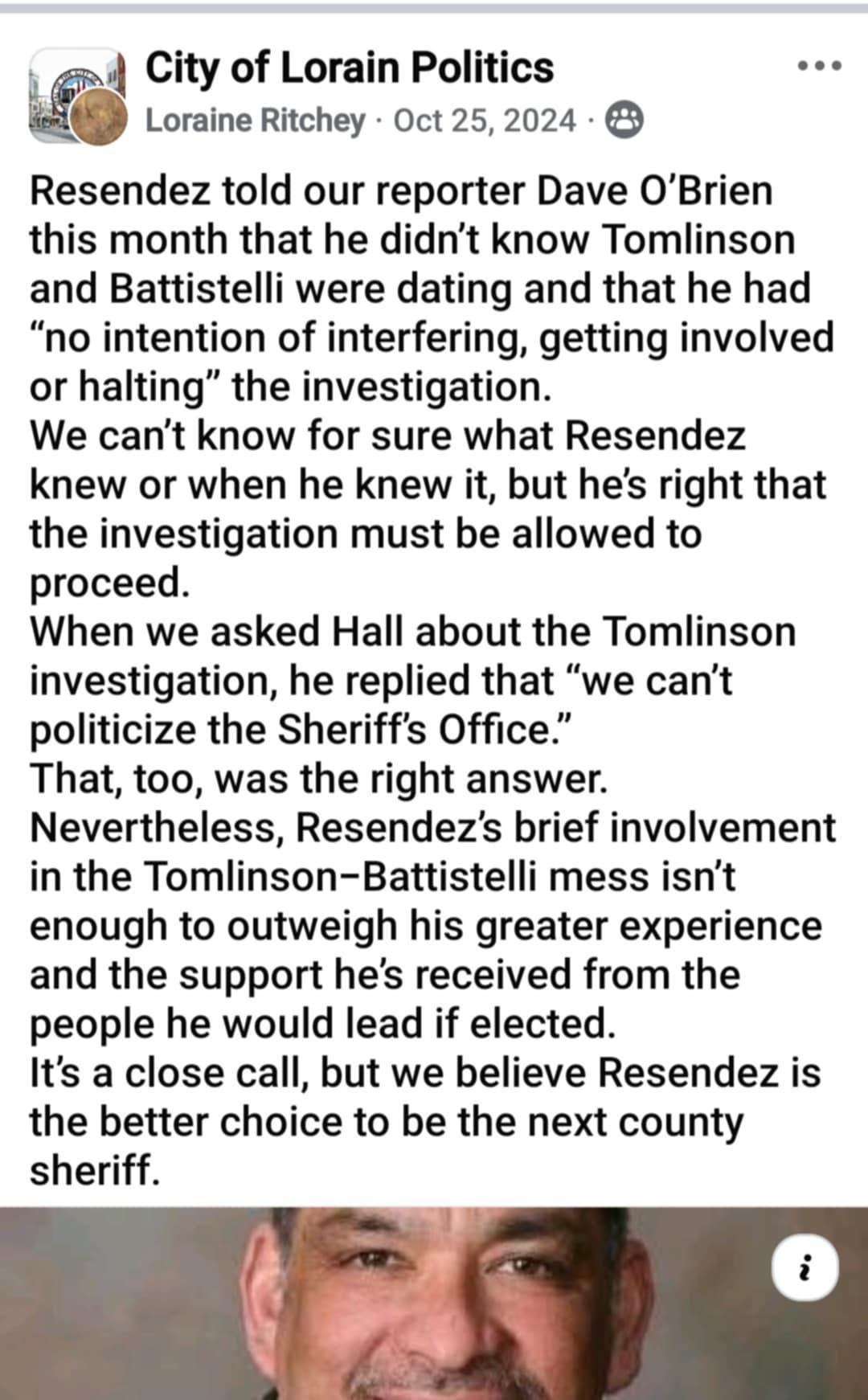

Adding fuel to the fire, a post by the “City of Lorain Politics” Facebook page, dated October 25, 2024, quotes Resendez telling reporter Dave O’Brien that he “didn’t know Tomlinson and Battistelli were dating” and that he had “no intention of interfering” in the matter. The public relations pivot was evident—Resendez was attempting to downplay involvement amid mounting political scrutiny.

Yet this directly contradicts sworn testimony and public records already available by that time. Resendez had already been a named party to the HR investigation into Battistelli, received the original complaint from Longacre, and communicated concerns internally—there is no credible basis to assert ignorance.

These contradictions raise serious concerns about the politicization of the Sheriff’s race and the reliability of public statements made by a candidate who had a material role in the county’s most explosive personnel scandal in years. His selective amnesia appears timed to preserve political viability rather than to reflect the truth.

Resendez’s denial was not a harmless oversight—it was a deliberate act of omission designed to obscure a paper trail that already had his name on it. Whether that constitutes ethical misconduct may be up for debate. Whether it was misleading is not.

This kind of revisionism isn’t just dishonest—it undermines public trust. Voters deserve accountability from those who seek to lead law enforcement. In this case, Resendez offered spin instead of transparency, denials instead of documentation, and political calculus over public integrity.

In the end, it wasn’t Tomlinson’s affair that undid him—it was the man he trusted most. Burge’s August 11, 2023 letter to discipline Battistelli triggered her EEOC complaint, Tomlinson’s physical outburst, the $100,000 payout, and eventually the loss of his job and public reputation. Burge, the mentor, may have signed the very document that ensured his protégé’s political demise.

Legal Disclaimer: This report is based on sworn depositions, EEOC filings, and public records. While every effort has been made to present verified and accurate information, readers are advised that this is an independent analysis and not a legal finding. Always consult primary documents or legal counsel for official interpretation.

Thoughts by the Author:

What happened inside the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office was not just an HR failure—it was a systemic collapse driven by ego, favoritism, and fragile men clinging to power. The record shows a woman of color advocating for her peers, punished by a cadre of white men more interested in protecting the club than the public. The three-man coalition of Burge, Resendez, and Petticord decided that Battistelli had to go—and they made it happen.

It is easy to blame the romance. But that’s a distraction. The real issue is retaliation—an entire county office more comfortable silencing a woman than addressing its own misconduct. And at the core of it all? Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord, the shapeshifter of this sordid tale. It was his early shrug, his indecision, his failed leadership that set the train in motion. He enabled the cover-up, then pretended it was above his pay grade.

Next up: Petticord’s Deception – Who Knew What, and When?