Judge Bremke Shut the Door Without Touching the Law

How the Court dismissed the City of Lorain firearm ordinance challenge on “standing,” reframed the harm, and handed the City a procedural exit instead of a merits ruling

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, LSW, BSSW

Investigative Journalist | Lorain Politics Unplugged

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

Introduction

What happened and why it matters

On February 18, 2026, Lorain County Common Pleas Judge Giovanna V. Bremke issued a final appealable order granting the City of Lorain’s motion to dismiss in Case No. 25CV219080. The plaintiffs filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief challenging a package of amended City ordinances that mirror existing state firearm related provisions but increase the penalties at the local level, elevating conduct that would otherwise be charged as lower level misdemeanors into first degree misdemeanor offenses under the City’s code.

This was not a minor adjustment to local law. The ordinances at issue effectively duplicate state law while increasing the consequences, raising serious questions about whether a political subdivision can impose harsher penalties in an area where the State of Ohio has already established a uniform regulatory framework. The lawsuit was filed to answer that question before enforcement, through a declaratory judgment and injunctive relief, which is exactly how constitutional challenges to statutes and ordinances are supposed to be brought.

The Court did not reach that question. It did not analyze whether the ordinances conflict with state law. It did not evaluate the statutory framework under Ohio Revised Code 9.68. It did not address whether the City exceeded its authority.

Instead, the Court ended the case at the threshold, ruling that the plaintiffs lacked standing. That means the Court did not decide whether the law is valid. It decided that the plaintiffs were not permitted to challenge it at this stage.

That distinction matters. Because when a case is dismissed on standing, the legal issue does not go away. It is not resolved. It is avoided.

Judge Bremke Shut the Door Without Touching the Law

A dismissal on “standing” that avoided the constitutional question and rewrote what counts as harm

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, LSW, BSSW

Investigative Journalist | Lorain Politics Unplugged

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

INTRODUCTION

The Court ended the case without ever touching the law

On February 18, 2026, Lorain County Common Pleas Judge Giovanna V. Bremke issued a final appealable order dismissing the lawsuit challenging the City of Lorain’s firearm related ordinance amendments. The case sought declaratory and injunctive relief. It was designed to ask a simple question. Can the City increase penalties in a way that conflicts with state law.

That question was never answered.

Instead, the Court dismissed the case at the threshold, ruling that the plaintiffs lacked standing. The ruling did not say the ordinance was lawful. It did not say the arguments were incorrect. It said the plaintiffs were not allowed to ask the question in court.

That is not a merits decision. That is a gatekeeping decision.

And when a court uses standing this way, the focus shifts from whether the government acted lawfully to whether the public is even allowed to challenge it.

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK THE COURT USED

Standing became the entire case

The Court relied on a familiar principle. Before a court can decide a case, the plaintiff must have standing. That means the plaintiff must show an injury, that the injury is connected to the defendant’s conduct, and that the court can provide relief.

On paper, that is a neutral rule. In practice, it can become a tool.

Because if a court defines injury narrowly enough, no one can ever meet the standard without first being harmed.

That is what happened here.

The Court acknowledged that pre enforcement challenges exist. It acknowledged that a plaintiff does not always need to wait until harm occurs. It even cited the standard that a “significant possibility of future harm” can be enough.

Then it declined to apply that standard in any meaningful way.

The procedural reality

We were not even notified before the decision became public

There is another part of this that cannot be ignored, because it goes to the basic integrity of the process.

We were not served with this ruling before it became public.

There was no immediate notice, no direct communication that the decision had been issued, no opportunity to review the order as counsel or as parties to the case before it entered circulation. Instead, we learned about the dismissal the same way the general public did. We saw it in the media.

That matters.

Because service is not a technical formality. It is how the Court communicates its rulings to the parties whose rights are directly affected. It is how deadlines are triggered. It is how a party knows when the clock starts for post judgment motions or appeal. It is how due process is supposed to function in a live case.

When a ruling is issued and the parties learn about it through a newspaper before they receive formal notice from the Court, it raises serious questions about how the process is being handled. It creates uncertainty about timing, about deadlines, and about whether the procedural safeguards that are supposed to exist are actually being followed.

And it reinforces a broader concern that has been present throughout this litigation and others. That access to process is being treated as something flexible rather than something that must be strictly adhered to.

Standing as a gate, not a neutral rule

Against that backdrop, the Court’s reliance on standing takes on even greater significance.

Standing is supposed to ensure that courts decide real disputes. It is not supposed to be used as a way to avoid deciding difficult questions. But when a court narrows the definition of injury to the point that no plaintiff can meet it without first suffering enforcement, standing stops functioning as a neutral doctrine and starts functioning as a barrier.

The Court acknowledged the correct standard. It recognized that future harm can be sufficient. It recognized that pre enforcement challenges exist precisely so individuals do not have to wait until they are charged or prosecuted.

Then it applied a much narrower view in practice.

Instead of asking whether the ordinance creates a real and credible risk that affects the plaintiffs now, the Court reduced the issue to whether the plaintiffs had already been cited or were engaged in conduct that would lead to citation. By doing that, the Court effectively collapsed the concept of future harm into actual enforcement.

That is not what the standard says.

If the only way to establish standing is to show that enforcement has already occurred or is inevitable, then pre enforcement review becomes meaningless. It turns the question from whether a law is lawful into whether someone has already been harmed by it.

That is not how constitutional review is supposed to work.

And that is why this case did not turn on the ordinance. It turned on how narrowly the Court chose to define the word “injury.”

WHAT THE COURT SAID

The injury was reframed into something easier to dismiss

The Court’s reasoning comes down to one central move, and it is not complicated once you strip away the legal language.

It concluded that the plaintiffs’ alleged injury was nothing more than the possibility of facing increased penalties if they engaged in criminal behavior, and that this was not different from the general public.

That framing controls everything.

Because once the Court defines the harm that way, the case becomes easy to dismiss. If the only injury is punishment for criminal conduct, then anyone who obeys the law has no claim. And anyone who wants to challenge the law must first risk prosecution.

That is not a neutral interpretation of a pre enforcement challenge. That is a narrowing of the issue to the point where it disappears.

The plaintiffs did not file this case to argue that they want to commit crimes. They filed it to challenge whether the City has the authority to increase penalties in the first place. That is a legal question. It exists independently of enforcement. It exists the moment the ordinance is enacted.

But the Court’s framing avoids that question entirely.

The shift from legality to behavior

The decision reframes the issue away from what the City did and onto what the plaintiffs might do.

Instead of asking whether the ordinance conflicts with state law, the Court asks, in effect, whether the plaintiffs intend to engage in conduct that would trigger the ordinance. That is a completely different inquiry. One is a legal question about the limits of municipal authority. The other is a hypothetical about personal behavior.

That shift matters because it changes the nature of the case.

If the focus is on legality, then the existence of the ordinance itself is the issue. If the focus is on behavior, then the ordinance becomes irrelevant until someone violates it. That allows the Court to avoid analyzing whether the law is valid by insisting that no one is currently affected by it.

That is how a substantive challenge becomes a procedural dismissal.

The practical effect of the Court’s logic

Under the Court’s reasoning, the only way to establish standing is to show that you are at risk of being punished. And the only way to show that risk, under the Court’s framing, is to be engaged in conduct that could lead to punishment.

That creates a very specific problem.

It means a person cannot challenge the law as a law. They can only challenge it as a consequence. They must wait until the law is applied, or at least until they can demonstrate that they are likely to be subject to it in a way that goes beyond the general public.

But the ordinance applies to the general public. That is the nature of criminal law.

So the Court’s logic effectively says that because the law applies to everyone, no one can challenge it unless they are singled out for enforcement. And until that happens, the issue is considered too general to be heard.

That is not a small technical point. That is a structural limitation on access to judicial review.

Why that framing matters in a pre enforcement case

Pre enforcement challenges exist for a reason. They exist because constitutional rights are not supposed to be enforced by forcing people to become defendants first. They exist so that courts can determine whether a law is valid before it is used against someone.

The Court acknowledged that concept. It cited the standard that a significant possibility of future harm can be enough.

But then it treated the harm as if it only exists when a person is already facing punishment.

That collapses the distinction between pre enforcement and post enforcement challenges. It turns a preventative legal mechanism into a reactive one. It tells the public that the law cannot be reviewed until after it has been used.

That is not what the standard says.

The question that was never answered

Once the Court reframed the injury as punishment for hypothetical criminal conduct, the rest of the analysis was effectively over.

But that left the core issue untouched.

Does the City have the authority to enact ordinances that mirror state law while increasing penalties.

That question was never addressed.

It was not resolved.

It was avoided.

WHY THAT MATTERS

Pre enforcement challenges are supposed to prevent harm, not require it

The entire purpose of a pre enforcement challenge is to allow courts to review a law before someone is punished under it. That principle is not an academic concept. It is the mechanism that allows constitutional rights to be protected without forcing individuals to first suffer the consequences of enforcement.

If courts require prosecution before review, then the only way to challenge a law is to become the test case. That is not simply a higher bar. That is a structural shift in how the system operates. It turns constitutional review from a preventative safeguard into a reactive process that only occurs after harm has already taken place.

That creates a trap.

If you obey the law, you are told you have no injury because nothing has happened to you yet. If you risk violating the law, you expose yourself to arrest, charges, and the full weight of the criminal system. And if you are prosecuted, the harm is no longer theoretical. It is immediate, concrete, and often irreversible in its consequences.

That is not how constitutional review is supposed to work.

Courts have long recognized that individuals should not have to violate a law to challenge it. That is why pre enforcement challenges exist. They recognize that a law can cause harm not only through direct enforcement, but through the credible threat of enforcement and the changes it imposes on everyday conduct.

The Court acknowledged that “certain impending injury” can justify relief. It acknowledged that a significant possibility of future harm can be enough to establish standing. Those statements reflect the correct legal standard.

But the application of that standard is where the problem arises.

The Court treated the ordinance as if it creates no real world impact until someone is charged. It reduced the concept of harm to the moment of enforcement, as if the law has no effect on individuals until a citation is issued or a prosecution begins.

That ignores how criminal law actually functions.

Criminal statutes do not operate only at the point of arrest. They operate continuously. They influence decisions before any interaction with law enforcement occurs. They shape how people carry themselves in public, how they assess risk, how they respond to authority, and how they navigate situations where the line between lawful and unlawful conduct may not be perfectly clear.

When penalties are increased, those effects become more pronounced. The stakes are higher. The consequences of being accused are greater. The pressure to avoid even the possibility of enforcement increases. That is the deterrent function of criminal law. It is designed to influence behavior before enforcement happens.

That deterrent effect is not speculative. It is the intended operation of the law itself.

To say that no injury exists until prosecution is to ignore that reality. It treats the law as if it is dormant until activated by a charge, rather than as an active force that shapes behavior the moment it is enacted.

Pre enforcement challenges exist to address that reality. They recognize that harm includes the credible threat of enforcement, the increased legal exposure, and the pressure imposed by a law that may exceed the authority of the government that enacted it.

If that understanding is set aside, then the only way to test the legality of a law is to wait until it is used against someone or to place oneself at risk of being the person it is used against.

That is not prevention. That is requiring harm as a condition of review.

And once that becomes the standard, the protection that constitutional review is supposed to provide is no longer accessible when it matters most, which is before the law is enforced.

QUESTIONS OF IMPARTIALITY

Why the appearance of bias matters as much as actual bias

There is another issue that cannot be ignored, and it has nothing to do with the legal arguments in the case. It has to do with confidence in the process itself.

The legitimacy of any court decision depends not only on the law that is applied, but on the appearance that the decision was made by a neutral and independent judge. That is not a preference. That is a requirement of due process.

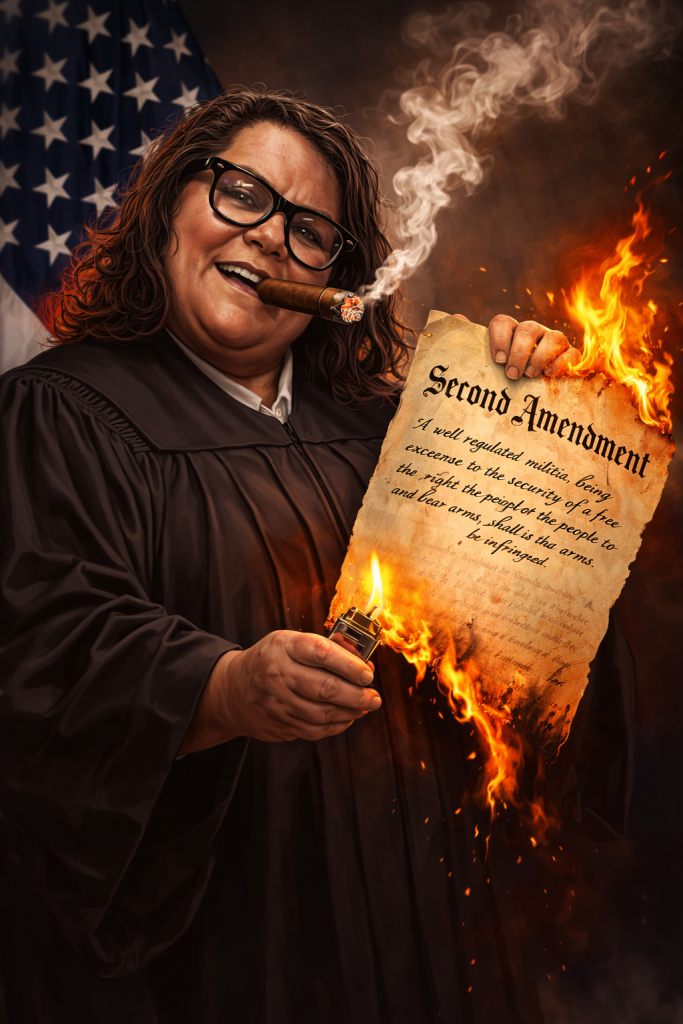

In this case, there are relationships and local connections that raise legitimate questions about whether that appearance of neutrality exists. Judge Bremke has longstanding ties to Lorain. In addition, there are known connections between individuals close to the Court and individuals doing business within the City of Lorain.

Those facts, standing alone, do not prove bias. Judges live in the communities they serve. They will inevitably have professional and personal connections. But when a case directly involves a local government entity, and when those connections intersect with that same community, the issue is not simply whether bias exists. The issue is whether a reasonable person could question whether the decision was made free from outside influence.

That standard matters.

Under the Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct, a judge must disqualify themselves in any proceeding in which their impartiality might reasonably be questioned. The rule does not require proof of actual bias. It focuses on the appearance of bias, because public confidence in the judiciary depends on the perception that decisions are made fairly and independently.

When a case involves a city government, and there are overlapping professional relationships within that same city involving individuals connected to the Court, it raises a legitimate question that should be addressed openly.

That is not an accusation. That is a question of transparency.

And when that question is combined with a ruling that resolves the case without reaching the merits, the concern becomes more pronounced. Because when a court avoids the substance of a challenge, the public is left with a result but without a clear answer to the underlying legal issue.

The standard is not whether anyone can prove bias. The standard is whether the situation creates a reasonable question about impartiality.

That question exists here.

And in a case involving the limits of government authority, that question is not something that can be ignored.

THE REAL WORLD EFFECT

Increased penalties are not theoretical

When a City increases penalties, it changes behavior immediately. It does not wait for the first arrest, the first citation, or the first prosecution. The effect begins the moment the law is enacted, because the law itself is a signal of risk.

It changes how police interact with residents. When the potential charge carries a higher penalty, the leverage in that interaction shifts. The tone changes. The stakes change. The consequences attached to any allegation become more serious, even before a decision is made about whether a charge will actually be filed.

It changes how prosecutors negotiate. Higher penalties do not just affect what happens at trial. They affect everything leading up to it. They influence charging decisions, plea discussions, and the pressure placed on an individual to resolve a case rather than fight it. The greater the potential penalty, the greater the leverage.

It changes how people assess risk in everyday situations. People do not operate in a vacuum. They make decisions based on potential consequences. When those consequences increase, behavior changes. People avoid situations, avoid interactions, and avoid anything that could potentially be misinterpreted or escalated.

Penalty increases are not just words on paper. They are leverage.

They increase the consequences of being accused, not just convicted. They increase the pressure to comply in situations where the law may not be clear or where authority is being exercised aggressively. They increase the risk of being wrongfully charged or overcharged, because the higher the available penalty, the greater the range of outcomes that can be imposed. They increase the stakes of every encounter with law enforcement, from the most routine interaction to the most serious allegation.

Those effects exist before a single charge is filed. They exist before a single case is opened. They exist because the law itself defines what can happen if an accusation is made.

To say that no harm exists until prosecution is to ignore how the system actually operates. Criminal law is not reactive. It is preventative. It is designed to shape behavior before enforcement occurs. The threat of enforcement is part of the law itself.

That is the deterrent function.

And when penalties increase, that deterrent effect becomes stronger. The law exerts more pressure, not less. The risk becomes more significant, not less. The consequences of being wrong become more severe, not less.

Ignoring that reality does not make it disappear. It only removes it from the legal analysis.

And that is exactly why pre enforcement challenges exist. They exist because the impact of a law is not limited to the moment someone is charged. The impact begins the moment the law is enacted. They allow courts to evaluate whether a law is lawful before its consequences are imposed on real people.

If that mechanism is removed, then the only way to challenge a law is to experience its consequences first.

At that point, the harm is no longer theoretical. It is already done.

R.C. 9.68 AND WHAT THE COURT’S OWN FINDINGS SHOW

The Court acknowledged the mismatch, then refused to address it

There is a point in the Court’s own decision that should not be overlooked, because it goes directly to the issue the case was supposed to resolve.

The Court identified the ordinances at issue and explained what they do. It noted that the City’s amendments mirror sections of the Ohio Revised Code, but increase the penalties from lower level misdemeanors to first degree misdemeanors.

That is not a disputed fact. That is the Court’s own description of the ordinances.

And that description matters.

Because Ohio Revised Code 9.68 is built on one central concept. Uniformity. The statute declares that the regulation of firearms is a matter of statewide concern and that laws governing firearms must be consistent throughout Ohio. Political subdivisions are not permitted to enact or enforce regulations that conflict with that uniform framework.

Uniformity is not just about whether conduct is legal or illegal. It includes how that conduct is defined and how it is punished. The penalty is part of the law. It is not separate from it.

When the state defines an offense and assigns a penalty, that is the rule. If a city takes that same conduct and assigns a different penalty, the law is no longer uniform. It is different.

The Court acknowledged exactly that scenario. It recognized that the City’s ordinances correspond to state law, but impose greater penalties.

That is the conflict.

The entire case was built around that question. Whether a city can take conduct already regulated by state law and increase the consequences attached to it. Whether that creates a second, non uniform layer of regulation that R.C. 9.68 was designed to prevent.

But instead of addressing that issue, the Court stopped at standing.

The contradiction in the decision

There is a contradiction built into the ruling.

On one hand, the Court describes the ordinances as mirroring state law while increasing penalties. On the other hand, it concludes that this does not create any injury to the plaintiffs because the conduct is already illegal.

Those two positions do not fit together.

If the penalties are different, then the law is different. And if the law is different, then the legal exposure faced by the public is different. That is not theoretical. That is a direct consequence of the ordinance itself.

The Court’s reasoning depends on separating the penalty from the underlying conduct. It treats the illegality of the conduct as the only relevant factor, while treating the increase in punishment as something that does not matter until enforcement occurs.

But penalty is not an afterthought. It is part of the regulation. It defines the consequences of being accused. It defines the risk. It defines the leverage the government has in any encounter involving that conduct.

If the penalty changes, the law changes.

And if the law changes, uniformity is affected.

Why this should have been decided on the merits

The purpose of R.C. 9.68 is to prevent exactly this kind of variation between local and state law. It exists so that individuals are not subject to different rules, different restrictions, or different consequences depending on where they are in the state.

The Court’s own findings establish that the City has created a different consequence for the same conduct. That is the issue. That is the question the case presented.

Does increasing penalties for conduct already governed by state law violate the requirement of uniformity.

That is not a hypothetical question. It is a legal question. It arises from the text of the ordinance and the text of the statute. It does not depend on whether someone has already been charged.

Yet that question was never answered.

The Court acknowledged the difference. It described the difference. It put the difference on the record.

And then it declined to decide whether that difference is lawful.

The issue that remains

Because the case was dismissed on standing, the core issue remains unresolved.

The ordinances still exist. The difference in penalties still exists. The question of whether that difference violates R.C. 9.68 still exists.

Nothing in the decision says the City is correct. Nothing in the decision says the ordinances comply with state law.

The Court simply declined to reach the issue.

And that leaves the central question exactly where it started.

If the state has established uniform firearm laws, can a city impose a different punishment for the same conduct.

That is the question that was presented.

And it is the question that will have to be answered somewhere else.

THE “CHILLING EFFECT” ISSUE

The Court treated deterrence like it does not exist

The complaint raised a straightforward point that goes to the core of how criminal law actually operates. When a government increases penalties, it changes behavior. It creates a chilling effect. That is not a political argument. That is the basic function of deterrence, which is the entire reason penalty structures exist in the first place.

The Court dismissed that point by stating that the conduct at issue is already illegal under state law, just with a lesser penalty. On its surface, that sounds logical. But that reasoning overlooks how the law functions in reality. It treats the legality of conduct as the only relevant factor and ignores the role that consequences play in shaping behavior long before a charge is ever filed.

Criminal law does not begin at the moment of arrest. It operates continuously. It influences how people act in public, how they assess risk, and how they respond to authority. The severity of the penalty attached to a law is not incidental. It is the mechanism that gives the law its force. If penalties did not matter, there would be no reason to increase them. Legislatures increase penalties precisely because they understand that higher consequences produce greater deterrence.

When penalties increase, deterrence increases. That is not theory. That is how the system is designed to work.

The Court’s analysis effectively assumes a clean line between lawful and unlawful conduct, as if people only adjust their behavior when they are deciding whether to commit a clear violation. That is not how real life operates. Most situations fall into gray areas. Facts are often disputed. Intent is often unclear. Encounters with law enforcement are not always predictable. The risk is not just whether a person intends to violate that law, but whether their actions could be interpreted as a violation.

That is where chilling occurs.

When penalties are lower, individuals may be willing to engage in conduct they believe is lawful, even if there is some uncertainty. When penalties are higher, that same uncertainty carries greater risk. The consequences of being wrong are more severe. The exposure is greater. The pressure to avoid any situation that could be escalated increases. As a result, people adjust their behavior, not because the law has changed in substance, but because the consequences have changed in magnitude.

That is the chilling effect.

It is not limited to clearly lawful conduct. It includes situations where individuals avoid conduct because of the risk of being accused, misinterpreted, or subjected to discretionary enforcement. It includes situations where the law is not perfectly clear or where enforcement decisions are not consistent. People do not just avoid illegal conduct. They avoid risk. And when the risk increases, behavior changes.

The increase in penalties also affects how the law is applied. Police officers exercise discretion in how they approach encounters, how they characterize behavior, and whether to escalate a situation. Prosecutors exercise discretion in how charges are filed and pursued. When higher penalties are available, that discretion carries more weight. The difference between a lower level misdemeanor and a first degree misdemeanor is not symbolic. It affects potential jail time, fines, and long term consequences. That changes the leverage in every interaction involving that conduct.

Those effects exist before a single charge is filed. They exist because the law defines what can happen if an accusation is made. The consequences are part of the law itself.

To say that no harm exists until prosecution is to ignore that reality. It treats the law as if it is dormant until activated by a charge, rather than as an active force that shapes behavior from the moment it is enacted. It removes deterrence from the analysis entirely, even though deterrence is the primary function of criminal penalties.

That is why pre enforcement challenges exist. They recognize that harm is not limited to the moment someone is charged. Harm includes the credible threat of enforcement, the increased legal exposure, and the pressure placed on individuals to conform their behavior to a law that may not be valid in the first place. They allow courts to examine those effects before the consequences are imposed.

By dismissing the chilling effect on the ground that the conduct is already illegal, the Court reduces the concept of harm to a single moment in time, the moment of prosecution. In doing so, it overlooks the broader and more immediate impact that the law has on behavior, discretion, and risk. That impact is not theoretical. It is how the system works.

R.C. 9.68 AND THE RIGHT TO CHALLENGE

A right that becomes meaningless if standing is defined too narrowly

The plaintiffs relied in part on Ohio Revised Code 9.68, which recognizes the right to bring a civil action when local firearm regulations conflict with state law. The statute does not simply declare uniformity. It provides a mechanism for enforcement. It allows a “person, group, or entity adversely affected” by a conflicting ordinance to seek declaratory relief, injunctive relief, and damages. In other words, it is not just a statement of policy. It is a tool designed to ensure that local governments comply with statewide firearm law.

The Court acknowledged that statute, but emphasized that it does not eliminate the requirement to establish standing. That is correct as far as it goes. A statutory cause of action does not automatically override constitutional standing requirements. Courts still require a plaintiff to show a sufficient connection to the dispute to justify judicial review.

But the problem is not the existence of a standing requirement. The problem is how that requirement is defined.

R.C. 9.68 uses the phrase “adversely affected.” That language is broader than “prosecuted” or “charged.” It does not require that a person first be arrested or cited. It recognizes that a law can have real effects before it is enforced. It recognizes that being subject to a non uniform regulatory scheme, one that differs from state law, is itself a form of harm.

If “adversely affected” is interpreted to mean only those who have already been charged, or those who can show that they intend to engage in conduct that will lead to a charge, then the statute loses its function. It no longer operates as a preventative mechanism. It becomes reactive. It only allows challenges after the law has already been applied.

That fundamentally changes what the statute is designed to do.

A uniformity statute without a meaningful way to enforce it before harm occurs is not a safeguard. It is a delayed remedy. It tells the public that a law may be invalid, but the only way to prove it is to be subjected to it first. That is not protection. That is exposure.

The Court’s approach effectively reads “adversely affected” as requiring something more concrete than the existence of a conflicting law. It treats the statute as if it only applies when the plaintiff can show individualized harm beyond what the public at large experiences. But firearm regulations, by their nature, apply broadly. They are not targeted at a single individual. They affect anyone who falls within their scope.

If the requirement for standing is defined so narrowly that no one can meet it without first being prosecuted, then the statute’s enforcement mechanism becomes illusory. The right exists on paper, but there is no practical way to exercise it before the consequences of the law are imposed.

That is not how constitutional safeguards are supposed to function.

Statutes like R.C. 9.68 are designed to prevent unlawful local regulation from taking effect unchecked. They are designed to allow courts to address conflicts before those conflicts result in arrests, charges, or penalties. They recognize that the existence of a non uniform law is itself a problem that can be addressed through the courts.

When standing is defined in a way that prevents that review, the statute is reduced to something far narrower than what it was intended to be. It becomes a tool for cleanup after harm occurs, rather than a mechanism to prevent harm in the first place.

And when that happens, the protection the statute is meant to provide becomes much harder to reach, not because the right does not exist, but because the path to enforce it has been effectively closed.

THE EXPECTED RESULT

This was not a surprise, it was part of the process

There is something that needs to be said plainly, because anyone who has followed this case or any of the related matters in Lorain County already understands it.

This outcome was expected.

It was discussed before the complaint was ever filed. It was built into the strategy from the beginning. It was understood as a likely step in the process, not an unexpected result. That expectation did not come from speculation or guesswork. It came from experience dealing with this system over and over again.

Anyone who has spent time challenging government action in Lorain County understands how these cases tend to move. Public records are delayed, narrowed, or denied. Complaints are redirected between departments. Responsibility is diffused so that no single office ever appears accountable. And when a matter finally reaches a courtroom, the focus shifts away from the underlying conduct and onto procedural barriers that can end the case before the substance is ever addressed.

Standing is one of those barriers.

It allows a court to end a case without deciding whether the government acted lawfully. It allows the court to avoid the central legal question entirely and instead focus on whether the person raising the issue has satisfied every technical requirement to even be heard. It turns the courtroom from a place where disputes are resolved into a place where access itself becomes the issue.

That is exactly what happened here.

A PATTERN, NOT A ONE OFF

This is not about a single ruling or a single judge. It is about a pattern that has repeated itself across multiple issues, multiple filings, and multiple interactions with both local government and the courts.

When the same sequence appears again and again, it stops looking like coincidence. It starts to look like structure.

Issues are raised. Records are requested. Complaints are filed. The response is delayed, narrowed, or redirected. And when the matter finally reaches the point where it should be decided on the merits, the focus shifts to whether the person raising the issue is allowed to be heard at all.

That pattern matters because it shapes outcomes before the merits are ever reached. It determines whether the public ever receives a direct answer to the question they are asking, or whether the issue is simply pushed aside through procedural reasoning.

In this case, the question was simple. Can the City of Lorain increase penalties in a way that conflicts with state law.

That question was never answered.

THE APPEARANCE OF IMPARTIALITY MATTERS

There is another issue that cannot be ignored, because it goes directly to public confidence in the judicial process.

Courts do not operate in a vacuum. Judges live in the communities they serve. They have professional relationships, personal connections, and longstanding ties within those communities. That is not unusual. It is expected.

But when a case directly involves a local government, and when there are overlapping relationships within that same community involving individuals connected to the Court, the issue is not simply whether any actual bias exists. The issue is whether the process appears impartial to a reasonable observer.

That standard matters.

Under the Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct, a judge must disqualify themselves in any proceeding where their impartiality might reasonably be questioned. The rule does not require proof of actual bias. It focuses on the appearance of bias, because the legitimacy of the judicial system depends on public confidence that decisions are made independently and without influence.

In this case, there are connections within the Lorain community that intersect with the very entity involved in this litigation. There are business interests operating within the City that require approval, licensing, and interaction with the same municipal legal and administrative structure that is a party in this case. When those business interests involve individuals connected within the same professional and personal circles as the Court, it creates an overlap that raises legitimate questions about independence.

For example, a private business operating within the City, including establishments such as a cigar bar, does not exist in isolation. It requires compliance with local regulations, licensing, and in many cases interaction with the City’s legal and administrative departments to operate. Those departments are the same ones defending the City in litigation.

That overlap does not automatically establish bias. But it does raise a question that cannot be ignored.

When the same legal authority that is defending the City also plays a role in regulating or approving business activity connected to individuals within the same local network, a reasonable person can question whether the process is fully independent.

That is not an accusation. That is a question of structure.

And when a case involving that same City is resolved on procedural grounds without ever reaching the merits, that question becomes more significant, not less. Because the public is left without an answer to the legal issue and without clear assurance that the decision was made entirely free from influence.

Transparency matters in those situations.

THIS CASE WAS BUILT FOR WHAT COMES NEXT

Because of that pattern, this case was never structured as a one step process.

The arguments were made. The record was built. The legal framework was laid out. And the possibility that the case would be dismissed on procedural grounds before reaching the merits was anticipated from the beginning.

That is not defeat. That is how these cases move.

When a case is dismissed on standing, the issue does not disappear. It moves. It moves to the appellate level, where the question becomes whether the trial court correctly applied the law in refusing to hear the case at all.

That is the next stage.

Because the central question raised in this case has not been resolved. The Court did not say the City is correct. It did not say the ordinances are lawful. It did not address the substance of the claim.

It simply declined to reach it.

And when a court declines to answer a legal question that affects the public, that question does not go away.

It moves forward.

THIS CASE WAS BUILT FOR APPEAL

The record is already in place

From the beginning, this case was built with the understanding that it might not be resolved at the trial court level.

The arguments about pre enforcement standing were included for a reason. The statutory framework was included for a reason. The concept of impending harm and deterrence was included for a reason.

Because when a case is dismissed on standing, the record becomes the appeal.

Every argument is preserved. Every standard is on the record. Every framing choice made by the Court is visible.

The issue now is not whether the ordinance is constitutional. The issue is whether the Court was correct in refusing to hear the challenge at all.

That is a legal question. And it is one that does not end at the trial court.

FINAL APPEALABLE ORDER

This is the next step, not the last one

The Court designated the ruling as a final appealable order.

That matters.

It means the case now moves to the appellate court, where the focus shifts. The appellate court will not be deciding the ordinance at this stage. It will be deciding whether the trial court correctly applied the law of standing.

It will be deciding whether a pre enforcement challenge can be dismissed by redefining the alleged harm as nothing more than punishment for hypothetical criminal conduct.

It will be deciding whether the public must wait to be prosecuted before they can challenge a law that changes the consequences they face.

That is the real question now.

FINAL THOUGHT

The issue did not go away, it was pushed forward

The Court closed the case. It did not resolve the issue.

Nothing about this decision answers the question that was actually presented. The ordinances still exist. The increased penalties still exist. The legal conflict that was raised still exists. The arguments were not rejected on their merits. They were not weighed, analyzed, or decided. They were avoided through a procedural ruling on standing.

That distinction matters because a dismissal on standing is not a determination that the law is valid. It is a determination that the Court will not address the law at all. The question remains exactly where it started, unanswered and unresolved.

And that is why this is not the end of the case.

This moves forward.

An appeal will be filed. The next step is the Ninth District Court of Appeals, where the issue is no longer whether the ordinance is constitutional, but whether the trial court correctly refused to hear the challenge in the first place. That is a legal question. It is a review of whether the law was applied correctly, whether the standard for standing was properly understood, and whether a pre enforcement challenge can be dismissed by narrowing the definition of injury to the point where it no longer functions.

The position here is clear. There is standing.

Standing does not require a person to be arrested, charged, or prosecuted before they can challenge a law that changes their legal exposure. Standing does not require someone to put themselves in harm’s way just to gain access to the courts. The law recognizes that a credible threat of enforcement, a change in legal consequences, and the deterrent effect of increased penalties are all real world impacts. Those impacts exist the moment the ordinance is enacted.

To say otherwise is to turn pre enforcement review into something it was never meant to be. It forces individuals to choose between compliance and silence or risk and exposure. That is not a functioning system of constitutional review. That is a system that delays review until after harm occurs.

That is why this ruling cannot stand as the final word.

There is also a broader concern that goes beyond this single case.

Public confidence in the courts depends on the belief that cases are decided fairly, independently, and on the merits. When issues are consistently resolved on procedural grounds without reaching the substance, and when those rulings occur within a tightly connected local system where government, legal departments, and community relationships overlap, it raises serious concerns about whether the process is operating as it should.

That concern is not about personal attacks. It is about structure. It is about whether a reasonable person looking at the system would believe that it is fully independent and willing to address claims against local government on their merits.

That question exists here.

And it becomes more significant when the effect of a ruling is to prevent the underlying issue from ever being heard.

This case is not over.

The issue has not been decided. The law has not been tested. The arguments have not been resolved. What happened here was a refusal to reach the merits, not a determination of them.

So the question moves forward.

It moves to the appellate court. It moves to a forum that will have to decide whether this case should have been heard, whether standing was improperly denied, and whether the public can challenge a law before it is enforced.

Because when a court says you cannot challenge a law without showing injury, the next question becomes unavoidable.

What counts as injury when the purpose of the case is to prevent harm before it happens.

That question was not answered here.

It was passed forward..

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

The information contained in this article is based on publicly available records, court filings, statutes, and other source materials believed to be accurate at the time of publication. This article reflects the author’s analysis, interpretation, and opinion of those materials and is provided for informational, journalistic, and commentary purposes.

Nothing in this publication constitutes legal advice. Readers should not rely on this content as a substitute for professional legal counsel. Individuals seeking legal guidance should consult a licensed attorney regarding their specific situation.

Any references to individuals, public officials, or entities are based on documented records and are presented in the context of matters of public concern. Statements of opinion are clearly presented as such and are protected under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution.

The author makes no claim regarding the ultimate legal outcome of any matter discussed. All individuals and entities referenced are presumed to be in compliance with applicable laws unless and until determined otherwise by a court of competent jurisdiction.

If any factual error is identified, corrections will be made upon verification.

COPYRIGHT AND TRADEMARK NOTICE

© 2026 Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

This article and all associated content, including text, layout, design, and original analysis, are the intellectual property of Knapp Unplugged Media LLC and may not be reproduced, republished, or redistributed in whole or in part without prior written permission, except for brief quotations used for purposes of commentary, criticism, or news reporting in accordance with applicable copyright law.

“Knapp Unplugged,” “Lorain Politics Unplugged,” and all related branding are the property of Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. Unauthorized use of these marks is prohibited.

NOT LEGAL ADVICE NOTICE

This publication is intended for informational and journalistic purposes only and does not create an attorney client relationship. The author is not acting as legal counsel in this publication