How the Chronicle-Telegram “Found” the Petticord “Buried Salary” Email After I Put It in Their Inbox

By Aaron Christopher Knapp

Introduction

On December 9, 2025, The Chronicle-Telegram published an article by Dave O’Brien titled “Questions raised by April email about Commissioners’ personnel decisions.” Three days later, the Chronicle-Telegram Editorial Board followed with an editorial titled “Commissioners take a step backward on transparency.”

If a reader encountered only those two pieces, they would reasonably believe the story unfolded in a straightforward and orderly way. The Chronicle asked questions, public officials reacted, and transparency concerns surfaced as a result of the newspaper’s diligence and inquiry. That narrative is clean, simple, and reassuring to anyone who believes accountability flows neatly from institutional journalism to government.

That narrative is also incomplete.

This controversy did not begin in December, and it did not begin with the Chronicle’s questions. It began months earlier through a public records effort that was already underway before I became directly involved. An anonymous requester using the handle “SenseiCobra” initially submitted the public records request seeking the Petticord email and related communications. That request identified the issue, named the subject matter, and set the process in motion while the matter was still being quietly managed inside county government.

After that request stalled and meaningful answers were not provided, I stepped into the process. I joined the records fight openly, escalated the demand for compliance, and pressed for production after weeks of delay and nonresponse. At that point, the request had already been pending for a significant period of time, and the resistance to disclosure was well established.

During that period, the Prosecutor’s Office did not provide a timeline, did not acknowledge the request promptly, and did not resolve the issue without sustained pressure. When I publicly criticized that failure and referred to the conduct as unlawful, I was chastised by Chief Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Leigh Prugh for calling members of the office “losers,” even as the records request continued to languish without resolution. That criticism addressed my language rather than the delay itself, even though my statement was protected speech and the underlying public records obligation remained unmet.

Only after weeks upon weeks of pressure did the process move forward and the records begin to surface. By that point, the existence of the Petticord email had already been identified, its contents had already been described before release, and the issue had already been framed as a transparency dispute through the public records channel rather than through media inquiry.

This article documents how that record was built, how the Chronicle later stepped into a story that was already active and contested, and how the paper erased the origin of the controversy by presenting a discovery that had already occurred. This is the second time this has happened, and the repetition is what makes the pattern impossible to ignore.

Receipts From the Public Records Thread That Put the Story in the Open

The timeline is not a matter of opinion, and it does not require anyone to take my word for what happened. The record is in writing, with dates, recipients, and a paper trail that shows the story existed long before the Chronicle acted like it had “found” it.

On Thursday, October 9, 2025 at 11:42 PM, an email was sent from justice4loraincounty@proton.me to officials inside Lorain County government, including Erik Xamba, Monica Pluta, and tupton@loraincounty.us, with Tony Cillo and Leigh Prugh copied. The message invoked Ohio Revised Code 149.19 and formally requested “all email communications” between Daniel Petticord and Commissioner Jeff Riddell from February 15, 2025 through April 30, 2025, and it spelled out the subject matter so there could be no later confusion about what was being sought. The request specifically listed “the duties of the County Administrator,” “the County Deputy Administrator,” “pay raises,” “Personnel Summary Sheets,” and “opinions or interpretations of the ORC and Administrative Code,” as well as “county policy, procedure, and resolutions regarding the same.”

Most importantly, the requester did not present this as speculation. The October 9 request stated directly that the requester already knew the emails existed and even described one by its opening language, saying that a specific email had “Shhhhh” in the first two lines of the body and that it referenced resolutions tied to the administrator and deputy administrator. That detail matters because it shows the story’s centerpiece was identified inside the records request weeks before any newspaper coverage framed it as a December discovery.

After that October 9 submission, the follow up on October 17, 2025 makes the next key point. It states that eight days had passed “with not even acknowledgement that my request was received,” and it asks for an estimated time for fulfillment. That is the beginning of the documented delay, and it shows the transparency issue was already active and contested in October, while the public still had no access to the underlying email and while the government’s response was effectively silence.

It was after that delay and during that ongoing dispute that I entered the thread and escalated the pressure. On Saturday, October 18, 2025 at 10:52 AM, I responded into the same chain and I wrote, “They are losers who can’t follow the law.” The point here is not whether anyone liked my phrasing, because public records compliance does not turn on politeness and it does not become optional when a requester is angry. The point is that this comment triggered a reaction from the Prosecutor’s Office that focused on tone rather than timeline.

On Monday, October 20, 2025 at 9:33 AM, Chief Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Leigh S. Prugh replied to me directly, and she did so in writing in the same email chain. She wrote, “How curious to hear from you in an email string in which it appears you were never copied,” and she then stated, “I’m responding simply to say that neither my colleagues nor my boss are ‘losers who can’t follow the law.’ These interjections are unhelpful. If you must direct your ire to anyone in this office, please just save it for me.” That response is a receipt that matters because it documents two things at once. It documents that I was publicly chastised for protected speech while a records request was still being delayed, and it documents that the Prosecutor’s Office was already intertwined in the dispute in October, long before the Chronicle later wrote the story as if the controversy sprang to life only after its December inquiries.

The thread continued to show the core problem, which was not “drama” or “hostility,” but delay and gatekeeping. On October 22, 2025 at 10:52 PM, the requester wrote again that the request had gone on two weeks “with no response or estimated timeline,” and the email referenced the reality that an IT search can be performed quickly when government chooses to do it. The email also clarified that I was included in the original request through blind copy, and it framed that choice as accountability, which further undercuts any later suggestion that the controversy began only when a newspaper decided it was time to ask questions.

Then, on Thursday, October 23, 2025 at 7:46 AM, Prugh wrote a message that effectively admitted the delay and shifted responsibility to county administration. She wrote, “Our office has requested the records, and as soon as they are provided, we will review them,” and she continued, “because we have not yet received the emails from the administration, I’m afraid there is no way for this office to know how many there are, and as a result we cannot provide an estimated completion date.” That message is a key factual marker in the timeline because it confirms, in writing, that the Prosecutor’s Office did not have the emails yet and could not estimate completion, which is exactly what the public experiences when government wants sunlight to arrive on a schedule that protects officials rather than informs citizens.

Finally, on Sunday, October 26, 2025 at 4:43 PM, Prugh sent the production notice. She wrote, “Attached please find a folder of records that are responsive to your request,” and she added that these were “the only emails that matched the search criteria, as they are understood by the County,” while inviting further clarification if there was concern about missing records. That line matters because it marks the moment the records were produced, and it also demonstrates that the County retained control over what “matched” and what did not, even as the requester had already described the existence of a specific “Shhhhh” email at the beginning of the process.

This is the exact timeline that gets erased when later reporting implies the story was triggered by December inquiries or “found” through the Chronicle’s effort alone. The record shows that the fight to obtain the emails, identify their existence, and force production was already underway in October, and it shows that the people now positioned as responders or commentators were already copied, engaged, and participating in the dispute while the request was still being delayed.

This Story Did Not Start in December

This controversy began in October, and it began in the only place that matters under Ohio law: the public records channel governed by the Ohio Revised Code. On October 9, 2025, a formal public records request was submitted seeking all email communications between Daniel Petticord and Commissioner Jeff Riddell for the period of February 15, 2025 through April 30, 2025, pursuant to Ohio Revised Code 149.43 and the definition of a public record set forth in Ohio Revised Code 149.011(G). Under those statutes, emails created or received by public officials in the course of public business are records of the office, regardless of where they are stored or how uncomfortable their contents may be.

This was not a fishing expedition and it cannot honestly be characterized as speculative. The request was precise and deliberate. It identified the subject matter with specificity, including pay raises, personnel summary sheets, the duties and authority of the county administrator and deputy administrator, and any opinions or interpretations of the Ohio Revised Code, the Ohio Administrative Code, county policy, county procedure, and county resolutions relating to those issues. That level of detail matters because Ohio courts have repeatedly held that a requester is not required to guess at magic words or to narrow a request beyond what is reasonably necessary to identify the records sought.

More importantly, the request did not ask whether such emails might exist. It stated plainly that the requester already knew they did. The request described a specific email by its opening language, identifying it as beginning with the word “Shhhhh,” and explained that it referenced resolutions tied to the county administrator and deputy administrator. It further asked that the emails be preserved and produced, invoking the well established principle under Ohio public records law that records cannot be destroyed or concealed once a request has been made and notice has been given.

Leigh Prugh, the Chief Assistant Prosecuting Attorney for Lorain County and the designated legal counsel for the Board of Commissioners under Ohio law, was copied on the request from the outset. That fact is not incidental. Under Ohio Revised Code 149.43(B), a public office has an affirmative duty to promptly prepare and make available public records, and the involvement of the county’s legal counsel underscores that this was not an informal inquiry or a casual complaint. It was a formal invocation of statutory rights, delivered directly into the offices responsible for compliance.

This was not rumor, and it was not hindsight. It was a targeted, informed request grounded in concrete knowledge of what existed on county servers and how county business was being conducted. The existence of the Petticord email was identified before it was released. Its subject matter was described before it was produced. The legal implications were raised before any newspaper framed them as a newly discovered concern. By the time the Chronicle wrote as though the story emerged in December, the record shows that the story had already been alive, contested, delayed, and forced forward under the Ohio Revised Code weeks earlier.

What Happened Next and Why It Matters

After the October 9, 2025 public records request was submitted, nothing happened in the way Ohio law contemplates. There was no acknowledgement of receipt, no good faith estimate of when the records would be produced, and no indication that the request was being promptly processed as required by Ohio Revised Code 149.43(B). Days passed without response. Follow up emails were sent. Those follow ups did not ask for favors or special treatment. They asked for the minimum the statute requires, which is acknowledgment and a reasonable timeline.

As the silence continued, the correspondence escalated in a way that is familiar to anyone who has litigated public records in Ohio. The possibility of filing in the Ohio Court of Claims was raised, not as a threat, but as the statutorily provided enforcement mechanism when a public office fails to comply with its obligations. Ohio Revised Code 2743.75 exists precisely because experience has shown that some records are not produced unless an enforcement path is clearly on the table.

Only after that sustained pressure did the Prosecutor’s Office provide a substantive response. In writing, the office acknowledged that it had requested the emails from county administration but stated that it could not estimate a completion date because the records had not yet been provided for review. That admission matters. It confirms that the delay was not caused by any ambiguity in the request, but by the internal handling of records after notice had already been given. Under Ohio law, internal routing problems do not suspend a public office’s duty to promptly make records available.

On October 26, 2025, the records were finally produced under Public Records Request number 2025-PRR-0262. That production included the April 11 email from Dan Petticord to Commissioner Jeff Riddell, the same email later quoted by the Chronicle-Telegram as the centerpiece of its December reporting. Along with the production, the County added a caveat stating that these were the only emails matching the search criteria “as understood by the County,” and suggested that further clarification might be required if records appeared to be missing.

That qualifier is itself revealing. It underscores that the production was not framed as a complete and transparent disclosure, but as a limited response controlled by the County’s own interpretation of the request, even though the request had already described a specific email by its opening language and subject matter. This is a common posture in contested public records cases, and it is one reason Ohio courts have repeatedly emphasized that doubts must be resolved in favor of disclosure.

This production event is the moment the April 11 Petticord email entered the public record in a way that could no longer be quietly managed, delayed, or denied. It was no longer an internal communication discussed behind closed doors. It was no longer something that could be dismissed as rumor or speculation. It existed as a disclosed public record subject to inspection, citation, and accountability.

That is when the email was found in any meaningful legal sense. It was not discovered by a newspaper inquiry in December. It was forced into the open through the public records process, after weeks of delay, follow ups, and pressure grounded in the Ohio Revised Code. The distinction matters because transparency does not begin when a reporter writes a story. It begins when the law is invoked, compliance is resisted, and disclosure is ultimately compelled.

The Chronicle Was Already Copied Before It Reported the Story

This is the point where the Chronicle’s origin story does not merely weaken. It collapses under its own weight, because the record shows that the newspaper was not an outside observer who later stumbled onto a controversy. It was placed on notice while the controversy was actively unfolding, and it was placed on notice by me.

On October 18, 2025, during an active and unresolved public records dispute governed by Ohio Revised Code 149.43, I sent an email reply into the same records request thread that had been pending since October 9. That reply was not selective or private. The CC list included Lorain County Prosecutor Tony Cillo and Chronicle-Telegram reporter Dave O’Brien, the same reporter who would later author the December 9, 2025 article presenting the Petticord email as something newly uncovered through Chronicle inquiries.

This matters because the October email thread was not vague or abstract. It contained the formal public records request itself. It contained repeated follow ups documenting delay and non acknowledgment. It contained explicit references to the Petticord communications, including the already identified April email discussing how salary information could be kept “buried.” It contained discussion of personnel summary sheets, administrator authority, and the legal implications under Ohio law. In short, it contained the entire factual and legal framework of the story that the Chronicle would later present to readers as if it had only come into focus in December.

When a reporter is copied on a public records dispute while it is actively occurring, the newspaper cannot credibly claim institutional discovery weeks later. Notice matters under Ohio law, and it matters just as much in journalism. Under Ohio Revised Code 149.43(B), a public office is deemed to have notice when a request is delivered to its representatives. In the same way, a newsroom cannot plausibly describe itself as discovering a controversy when its reporter was already sitting inside the documentary record while the fight over disclosure was still unresolved.

This was not a case where a reporter heard rumors and later decided to dig. This was a case where the reporter was directly sent the dispute, the request, the subject matter, and the escalation in real time. The Chronicle did not need to infer the existence of the email. It did not need to guess at its contents. It did not need to reconstruct the timeline. The story was placed into its inbox while the County was still delaying production and while the records were still being controlled.

The Chronicle is absolutely free to file its own public records request. It is free to obtain its own copies of documents. It is free to report on matters of public concern. What it is not free to do, if it expects to be taken seriously as a transparency watchdog, is to write an origin story that suggests it “found” an email that had already been identified, described, demanded, delayed, produced, and circulated to the very reporter who later claimed discovery.

That distinction is not semantic. It goes to authorship, causation, and credibility. The Chronicle did not ignite this controversy. It entered it after the fuse had already been lit, after the pressure had already been applied, and after the email had already been forced into the public record. Presenting the story otherwise does not merely simplify the timeline. It erases the work that made the story possible and replaces it with a narrative that flatters the institution at the expense of the truth.

Aaron C Knapp

The Timeline Problem With “First Time I’ve Seen It”

In its December reporting, the Chronicle-Telegram quotes Lorain County Prosecutor Tony Cillo as saying that when a Chronicle reporter told him about the Petticord email, it was the first time he had seen it. Standing alone, that quotation conveys institutional surprise and reinforces the paper’s broader narrative that the controversy emerged only after the Chronicle began asking questions.

The documentary record complicates that portrayal. The October public records dispute included an email chain in which Cillo was copied while the request was still active, unresolved, and escalating. That thread repeatedly referenced the Petticord communications and the existence of the April email itself, including the already identified language describing how salary information could be kept “buried.” Whether Cillo personally read every message in that chain is not the controlling issue.

There are entirely benign explanations for how those facts can coexist. Public officials are copied on messages they overlook. Long threads go unread. Attachments are missed. None of that requires accusing anyone of dishonesty, and none of it is the core problem here.

The problem is journalistic context. By printing a quote that implies institutional surprise without disclosing that institutional notice already existed weeks earlier, the Chronicle shaped the reader’s understanding of causation. The paper presented the controversy as something discovered by a reporter in December, when the record shows that the issue had already been exposed through a public records fight in October, with the same officials copied and aware that the communications were being sought.

Journalism demands context when context affects who caused an event to surface and when. In this case, the Chronicle presented discovery where the record shows exposure. That distinction matters, because discovery implies initiative and origination, while exposure reflects a process that had already begun, already encountered resistance, and already forced disclosure before the newspaper chose to frame the story for the public.

The Prior Retaliation the Chronicle Wants Forgotten

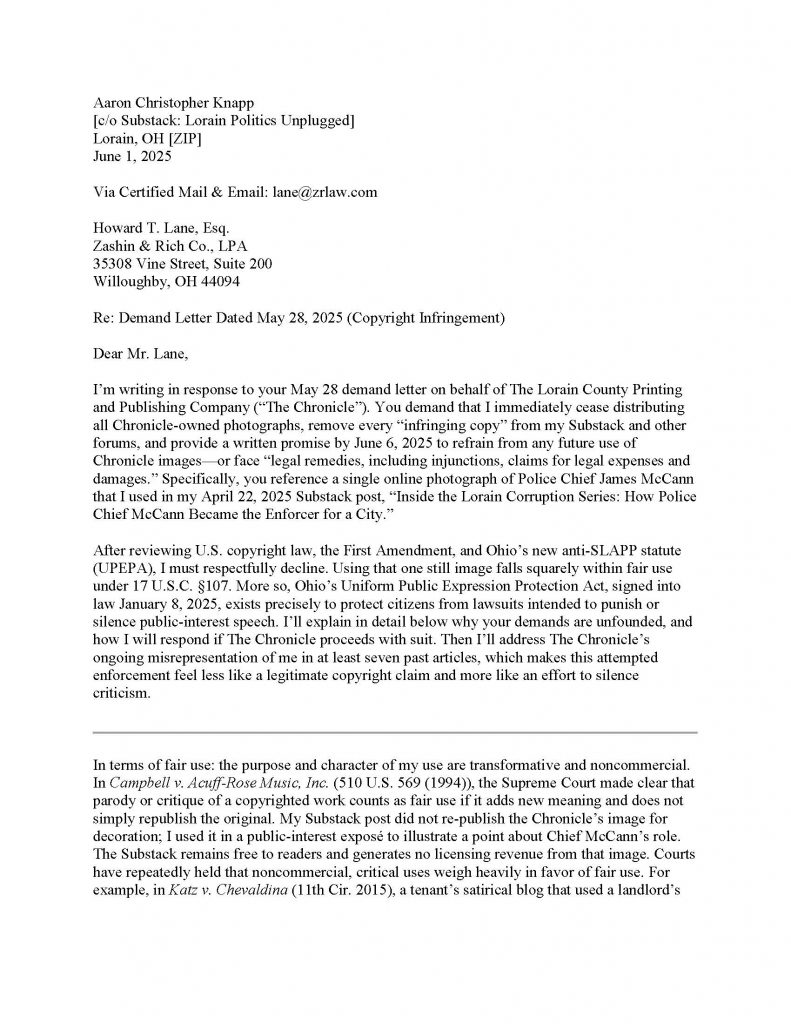

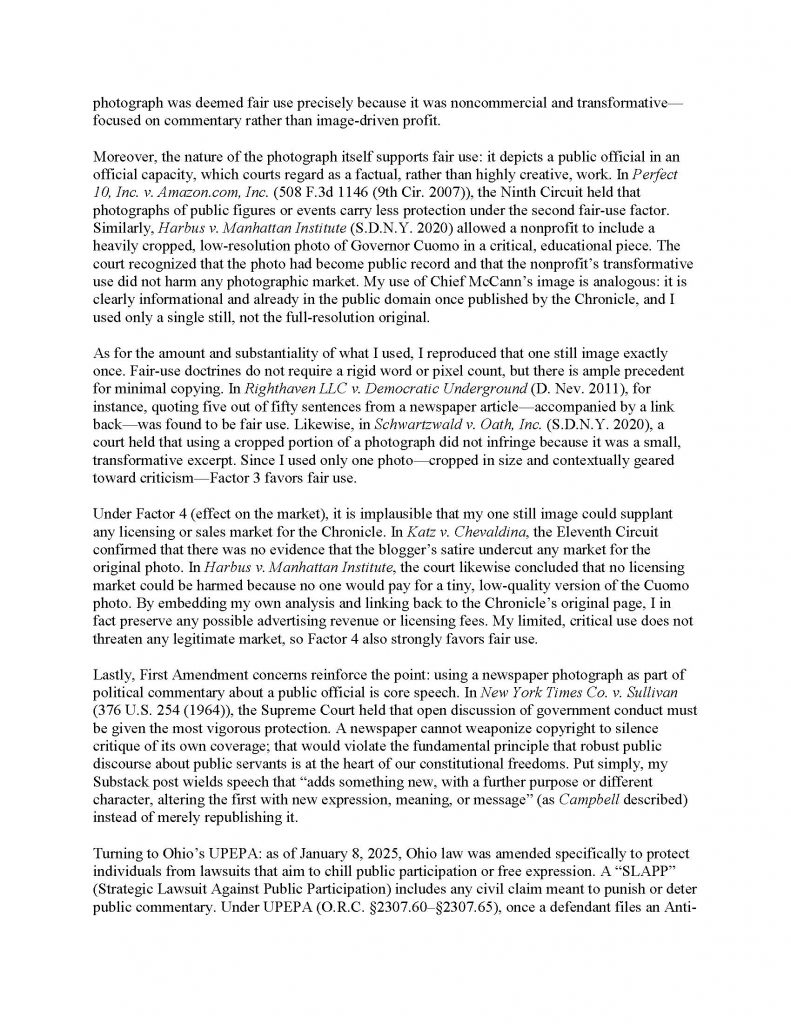

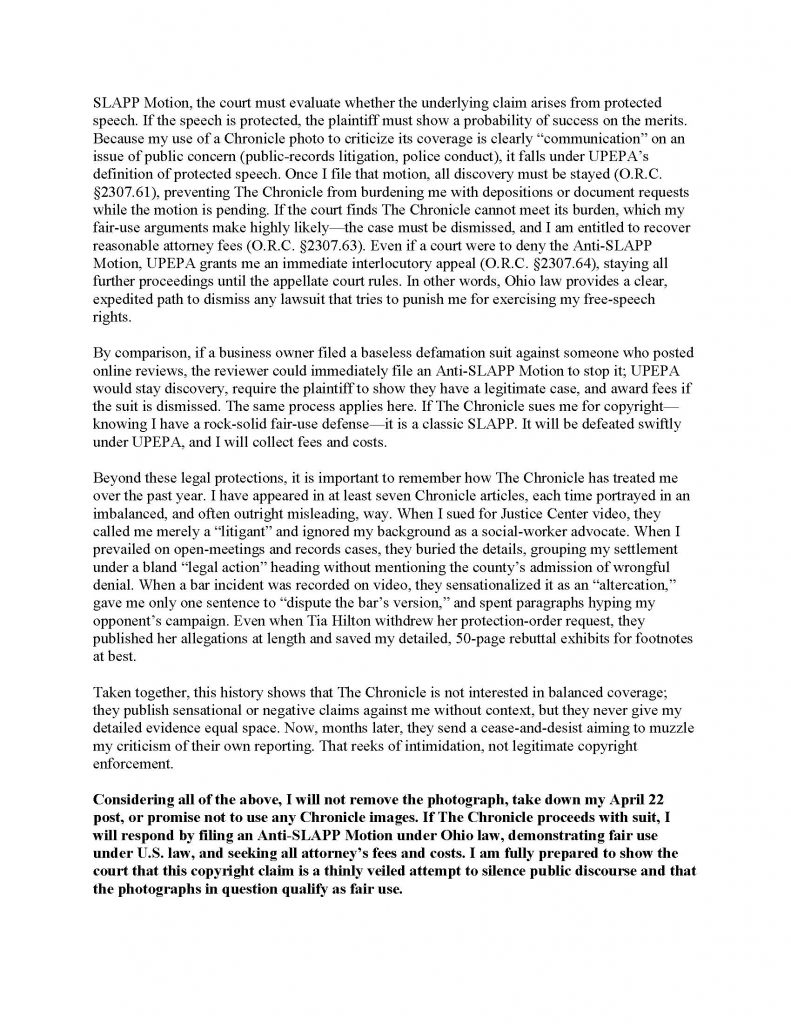

This dispute did not arise in a vacuum, and the Chronicle’s conduct around the Petticord email cannot be separated from its earlier attempt to silence criticism through legal intimidation. Months before the December personnel story, the Chronicle sent me a cease and desist letter through counsel over my use of a single still photograph of Lorain Police Chief James McCann in a critical Substack article. That photograph was freely available on the Chronicle’s own website, embedded for the purpose of commentary on a public official’s conduct, and used in a noncommercial, transformative context that falls squarely within well established fair use doctrine.

Rather than engage in dialogue, seek attribution, or even make an informal request, the Chronicle chose to escalate immediately to a lawyer letter. The demand threatened litigation against a paying subscriber who is also a disabled Army veteran, despite the fact that the post was free to the public and linked back to the Chronicle’s own reporting. The message was not subtle. It was not about copyright protection. It was about discouraging criticism of the Chronicle’s coverage and its institutional relationships.

That letter backfired. The legal theory was weak, the fair use analysis overwhelmingly favored commentary, and Ohio’s then newly effective anti SLAPP statute provided a clear path to dismissal and fee shifting if the Chronicle attempted to follow through. I made that clear, in writing, and the threat quietly evaporated. The Chronicle did not sue. It did not pursue the claim further. It simply moved on, without apology and without acknowledging that it had attempted to weaponize copyright law to chill protected speech about a public official.

This matters because it establishes context and motive. When a newspaper has already tried to silence a critic through legal pressure, its later decision to erase that same critic from the origin story of a major transparency issue cannot be viewed as accidental. The cease and desist letter demonstrates that the Chronicle was aware of my work, aware of my criticisms, and willing to use institutional power to suppress or marginalize them rather than engage on the merits.

It also matters because the Chronicle’s coverage of me, separate from the Petticord issue, has followed a consistent pattern. When I was physically assaulted at the MAHD House, law enforcement responded and injuries occurred. The Chronicle reported the incident, but framed it as controversy rather than violence, minimizing the fact that I was the victim of an undisputed assault. When Tia Hilton later filed a civil protection order based on false allegations and then dropped it, the Chronicle printed her claims prominently while burying my extensive rebuttal and the ultimate collapse of her narrative. When I prevailed in public records and open meetings litigation, the Chronicle reduced those outcomes to bland procedural summaries that stripped away the underlying misconduct.

Against that backdrop, the December personnel story reads differently. This is not a neutral paper stumbling into a complex timeline. This is an institution with a documented history of critical coverage, selective framing, and prior legal intimidation now presenting itself as the originator of a story that was already being forced into the open by someone it had previously tried to silence.

The fact that the earlier cease and desist episode is now invisible to the Chronicle’s readers is itself part of the laundering process. The paper wants the public to see a clean narrative in which it bravely discovers buried information and lectures officials about transparency. What it does not want readers to see is that, months earlier, it attempted to suppress criticism through a lawyer letter, and that the same critic later supplied the factual groundwork for the very story the Chronicle claims to have found.

That history is not incidental. It is probative. It shows that the Chronicle knew exactly who was pushing these issues, knew exactly where the pressure was coming from, and chose not to credit or even acknowledge that work when it became convenient to step in and rewrite the origin story.

The Editorial Board Completed the Rewrite

On December 12, the Chronicle-Telegram’s editorial board published a piece condemning the commissioners for retreating from transparency and rejecting the claim that workplace discomfort or internal tension justifies withholding public information. On the law, the editorial is correct. On the governing principles of open government, it is also correct. On the history of how this issue reached the public, it is materially and conspicuously incomplete.

What the editorial board presented as an institutional reckoning did not arise organically from the newspaper’s own investigative initiative. The facts underlying the editorial did not suddenly emerge because the Chronicle chose to look. They emerged because the information had already been identified, described, demanded, delayed, resisted, and ultimately forced into the open through sustained public records pressure weeks earlier. By the time the editorial board weighed in, the fight over the Petticord email and the personnel summary sheets was no longer hypothetical. It had already been waged.

An editorial that scolds elected officials for hiding information while omitting the very process that brought that information to light is not merely incomplete. It is self serving. Transparency is not just about condemning secrecy after the fact. It is about telling the public how secrecy was overcome, who challenged it, and how long the resistance lasted before it broke. When that context is stripped away, readers are left with the false impression that sunlight arrived because the newspaper flipped a switch, rather than because someone kept pushing when silence was the preferred response.

You cannot credibly demand transparency from public officials while declining to be transparent about your own role in the timeline. You cannot lecture commissioners about accountability while erasing the record showing that the story was already alive, already documented, and already circulating before the Chronicle chose to adopt it as an editorial cause. When the editorial board completed its rewrite, it did more than offer moral judgment. It quietly reassigned authorship of the story itself.

That is the core problem. The editorial board did not simply weigh in on a transparency issue. It laundered the origin of that issue by presenting the outcome without acknowledging the effort that made the outcome possible. In doing so, it mirrored the very behavior it condemned, substituting institutional convenience for full disclosure and leaving readers with a version of events that is cleaner than the truth but far less honest.

Why This Counts as Stealing in the Only Way That Matters

This is not a copyright dispute, and it is important to be precise about that at the outset. Copyright law protects original expression, not underlying facts, and the Supreme Court settled that principle decades ago. In Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991), the Court held that facts themselves are not owned by anyone, but it also made clear that originality resides in the selection, coordination, and effort involved in producing a work. That distinction matters here, not because anyone is claiming exclusive ownership of a public record, but because authorship, credit, and provenance still exist even when the material itself is public.

Journalism ethics recognize this reality even more clearly than copyright law. Plagiarism in journalism is not limited to copying sentences or paragraphs. It includes presenting someone else’s investigative work, sourcing, or discovery process as if it were your own. That is why attribution matters, even when everyone ultimately has access to the same documents.

An analogy makes the difference obvious.

If multiple reporters attend a public city council meeting, all watch the same livestream, and all later write stories about the possibility that council might remove livestreaming, no one “owns” that story. It is a public event, observed simultaneously, and each outlet is drawing from the same openly available source. Credit is unnecessary because discovery is collective and contemporaneous. No one had to force anything into the open. Nothing was hidden. Nothing was resisted. Everyone was standing in the same room.

That is not what happened here.

This story did not arise from a public meeting or a shared observation. It did not fall into a reporter’s lap by chance. It was not accidentally discovered through casual inquiry. It was produced through a targeted public records effort that identified a specific email before it was released, described its contents in advance, demanded its production under R.C. 149.43, endured delay and resistance, and ultimately forced the document into the public record.

Most critically, that work was not invisible to the Chronicle. The reporter who later authored the December article was copied directly on the records dispute while it was happening. The existence of the email, the subject matter, and the transparency implications were placed into his inbox in real time. That is not parallel discovery. That is direct notice.

When a reporter later writes as though the paper “found” the email through its own inquiries, that is not mere simplification. It is a reassignment of authorship. It takes a story that was gifted, fully formed, with context and history attached, and repackages it as institutional discovery.

This is where the ethical problem arises.

The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics requires journalists to “never plagiarize” and to “always attribute.” Plagiarism, in that context, includes appropriating another person’s reporting process or investigative labor without acknowledgment. By omitting the October public records fight, omitting the fact that the reporter was already copied, and omitting the months long effort that forced the email into daylight, the Chronicle did not merely leave out background. It rewrote causation.

That is why this feels stolen in the only way that actually matters. Not because words were copied. Not because a document was public. But because the origin of the story was erased and replaced with a cleaner, institution centered narrative that credited the newspaper with discovery it did not make.

There is a fundamental difference between reporting on a shared public event and claiming authorship over a record that was dragged into the open by someone else and handed to you along the way. Courtesy, transparency, and ethical reporting demand acknowledgment of that difference. When it is ignored, what is lost is not a legal right, but the integrity of the historical record itself.

Journalistic Ethics and the Duty to Tell the Whole Truth

Journalistic ethics are not aspirational slogans. They are operational standards that govern how stories are discovered, attributed, contextualized, and presented to the public. When those standards are selectively applied, the failure is not abstract. It directly affects public trust.

The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics sets out four core duties that frame responsible reporting.

First, journalists are instructed to seek truth and report it. That obligation includes rigorous fact checking, accurate identification of sources, and an affirmative duty not to distort information through omission or compression. Truth telling is not limited to what a document says. It includes how that document came to exist in public view and who forced it there.

Second, journalists are instructed to minimize harm. This duty includes showing compassion toward sources and subjects and recognizing power imbalances between institutions and individuals. When a large outlet erases the work of an individual who challenged government secrecy, the harm is not emotional only. It is reputational. It strips credibility from the very people who take risks to make public accountability possible.

Third, journalists are instructed to act independently. That includes resisting institutional convenience, political pressure, and the temptation to center the outlet rather than the facts. Independence is compromised when a newsroom quietly rewrites a timeline to present itself as the catalyst because doing so is cleaner and safer than acknowledging that the story originated elsewhere.

Finally, journalists are instructed to be accountable. Accountability includes correcting mistakes, inviting criticism, and exposing unethical practices within the media itself. That obligation applies inward as much as it applies outward. When a newsroom benefits from another person’s work without acknowledgment, accountability requires acknowledging that provenance, not burying it.

The Al Jazeera Code of Ethics, which is widely cited in international journalism circles, goes even further by explicitly acknowledging tensions that arise in competitive reporting environments. One of its most important provisions states that a media organization must welcome fair and honest competition without allowing the pursuit of a scoop to override professional standards. In other words, being first is never more important than being honest about how information was obtained.

That principle is especially relevant here. This was not a situation where multiple reporters independently stumbled upon the same document. This was not a public event observed by all at the same time. This was a targeted public records fight, conducted over weeks, with delays, resistance, and escalation, in which the existence and content of the document were identified before production and pressed into the open through persistence.

The ethical failure occurs when that process is erased and replaced with a simplified narrative that centers the institution rather than the truth. The Chronicle correctly rejected the commissioners’ argument that transparency should yield to discomfort, drama, or internal hostility. That same logic applies with equal force to journalism itself.

You cannot condemn public officials for withholding context while doing the same thing in your own reporting choices. You cannot demand transparency in government while obscuring the provenance of the very documents you use to scold that government. Transparency does not begin at publication. It begins with honesty about how information surfaced and who carried the burden of forcing it into view.

Sunlight is not a headline. It is a process. And some of us were standing in it long before the Chronicle decided it was safe to look.

Aaron Knapp

Closing

Transparency Requires Honesty About Who Turned the Lights On

This story does not end with an email, an editorial, or a carefully worded sentence about transparency. It ends with a question that goes to the heart of public trust, not just in government, but in journalism itself.

Who did the work.

The commissioners attempted to justify withholding personnel summary sheets by arguing that disclosure created drama, hostility, and discomfort. The Chronicle correctly rejected that rationale. Public discomfort is not a legal exemption. Institutional unease is not a justification for secrecy. Ohio law does not bend because transparency is inconvenient.

That same standard must apply to the press.

You cannot condemn elected officials for concealing process while doing the same thing in your own reporting. You cannot demand openness from government while quietly obscuring the provenance of the records that made your criticism possible. You cannot scold others for retreating from transparency while rewriting your own role in the timeline to appear cleaner, later, and safer than it actually was.

The Petticord email did not surface because a reporter asked a clever question in December. It surfaced because a public records request was filed in October. It surfaced because its existence was identified before production. It surfaced because weeks of delay were documented. It surfaced because pressure was applied. It surfaced because the law was invoked, resistance was met, and disclosure was compelled.

And critically, it surfaced with the Chronicle already copied.

That is not incidental. That is not a footnote. That is not background that can be safely omitted without consequence. That is causation.

This was not a shared public event where multiple reporters observed the same facts at the same time. This was not a city council meeting livestreamed for all to see. This was not parallel discovery. This was a targeted records fight over information that was being actively managed, delayed, and resisted, and the reporter who later claimed discovery was placed inside that fight while it was happening.

To later compress that history into a single sentence suggesting that the Chronicle obtained the email through its own request is not merely an editorial choice. It is a reassignment of authorship. It takes a process driven by law, persistence, and risk, and reframes it as institutional initiative. It erases the labor that made the story possible and replaces it with a narrative that flatters the institution rather than honors the truth.

That is why this matters.

Not because anyone owns a public record. Not because facts can be copyrighted. The Supreme Court settled that long ago in Feist v. Rural Telephone. Facts belong to everyone. But effort still exists. Process still exists. Attribution still exists. Journalism ethics recognize that even when the law does not.

When a newsroom benefits from someone else forcing a record into daylight and then presents that exposure as its own discovery, the harm is not legal. It is historical. It distorts how accountability actually works. It teaches readers that transparency flows from institutions downward, rather than from citizens pushing upward when institutions resist.

That lesson is dangerous.

It discourages people from invoking the law. It marginalizes those who take risks. It rewards silence and timing over persistence and pressure. And it leaves the public with a comforting fiction in which sunlight arrives neatly on deadline, rather than through conflict, delay, and insistence.

Sunlight is not a headline. It is not an editorial stance. It is not a sentence buried in the middle of a story.

Aaron Christopher Knapp, author of Sunlight Is a Headache for Somebody

Sunlight is a process.

It is a request filed when no one is watching. It is follow up after silence. It is escalation when delay becomes policy. It is standing in the open while institutions hope you will move on. It is insisting that the law means what it says, even when that insistence makes you inconvenient, abrasive, or unwelcome.

Some of us were doing that work long before December. Some of us were copied into the resistance. Some of us absorbed the hostility, the delay, and the dismissal that came before the story was safe enough for an editorial board to endorse.

Transparency demands honesty about that.

Not because credit is owed as a courtesy, but because truth requires an accurate account of how it came to light. If journalism wants to remain credible as a watchdog, it must be willing to tell that story too, even when it complicates the narrative, even when it shifts the spotlight away from itself.

You cannot condemn secrecy while practicing erasure.

You cannot demand accountability while laundering origin.

You cannot turn the lights on and pretend no one else reached for the switch.

Sunlight arrived here because someone kept pushing when silence was easier.

That is the truth.

Author Bio

Aaron Christopher Knapp is an investigative journalist, public records litigator, and licensed social worker based in Lorain County, Ohio. He is the founder and publisher of Lorain Politics Unplugged and the author of Sunlight Is a Headache for Somebody, a comprehensive guide to Ohio public records law built from lived experience, statutory analysis, and documented enforcement actions.

Knapp’s work focuses on government transparency, misuse of authority, retaliation against whistleblowers, and the systematic obstruction of public access to records. Over multiple years, he has forced the release of unlawfully withheld documents, prevailed in public records disputes, challenged unconstitutional ordinances, and documented patterns of institutional resistance to accountability across municipal and county government.

His reporting blends document driven investigation, statutory interpretation, and first person accountability journalism. Knapp does not rely on anonymous sourcing or speculative narratives. His work is grounded in verifiable public records, sworn filings, recorded proceedings, and contemporaneous correspondence obtained under the Ohio Revised Code.

In addition to his journalism, Knapp has worked in social services and forensic mental health settings, bringing a professional understanding of ethics, power dynamics, and harm reduction into his reporting. He is a disabled Army veteran and a long time advocate for civil rights, disability access, and lawful governance.

Knapp publishes independently to avoid institutional pressure, advertiser influence, or editorial interference. His guiding principle is simple and consistent. Government belongs to the people, and truth is not negotiable.

Legal Disclaimer

This publication is provided for informational and journalistic purposes only. Nothing contained herein constitutes legal advice, legal opinion, or legal representation. The author is not acting as an attorney, and no attorney client relationship is created by the publication, distribution, or reading of this work.

All references to statutes, case law, administrative rules, or legal procedures are provided for educational and explanatory purposes based on publicly available law and documented experience. Readers should consult a licensed attorney for advice regarding any specific legal matter or dispute.

The analysis and commentary presented reflect the author’s interpretation of public records and observable events and are not judicial findings or legal determinations.

Public Records Notice

This article is based on lawfully obtained public records acquired pursuant to the Ohio Public Records Act, Ohio Revised Code 149.43, and related provisions of Ohio law. Source materials include emails, correspondence, filings, meeting records, and other documents produced by public offices or otherwise made publicly accessible.

No sealed, confidential, or unlawfully obtained records were used. All records referenced were obtained through formal public records requests, voluntary disclosure, court filings, or other lawful means.

Excerpts and descriptions of public records are presented accurately and in context to the best of the author’s knowledge at the time of publication and are used for purposes of transparency, accountability, commentary, and public education.

Presumption of Innocence and Fairness Statement

All individuals referenced in this publication are presumed innocent of any criminal wrongdoing unless and until proven guilty in a court of law. The discussion of allegations, disputes, investigations, or criticisms is based on matters of public record and public concern and does not constitute an assertion of guilt or unlawful conduct.

The inclusion of any person’s name does not imply criminal liability, intent, or wrongdoing. Where allegations are discussed, they are attributed to their sources and contextualized within the available documentary record.

This publication examines systems, processes, and transparency obligations and does not purport to adjudicate criminal responsibility.

Use of Artificial Intelligence Disclosure

Artificial intelligence tools were used in a limited and assistive capacity during the drafting and editing process of this publication. AI was utilized solely for structural refinement, grammar review, and stylistic consistency at the direction of the author.

All factual assertions, investigative conclusions, legal interpretations, narrative framing, and editorial judgments are the original work of the author. No artificial intelligence system independently researched, sourced, verified, or generated factual content contained in this article.

The author retains full editorial control and responsibility for all published material.

AI Generated Image and Illustration Disclaimer

Some images or illustrations associated with this publication may be generated or modified using artificial intelligence tools. Such images are used for illustrative or editorial context only and are not intended to depict literal events, individuals, or locations unless explicitly stated.

AI generated images are not evidence and should not be interpreted as factual documentation. Any likenesses of public officials or settings are symbolic or editorial in nature and are used consistent with fair use principles for commentary, criticism, and news reporting.

Copyright and Fair Use Notice

This publication constitutes original journalistic commentary and analysis protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Any quoted material, excerpts, or images of public officials are used for purposes of news reporting, criticism, commentary, and public education and are believed to fall within the scope of fair use under United States copyright law.

All original text is © 2025 Lorain Politics Unplugged. Unauthorized reproduction of original content beyond fair use is prohibited.

Proudly powered by WordPress

Having read this I believed it was rather enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and energy to put this article together.

I once again find myself personally spending a significant amount of time

both reading and leaving comments. But so what, it was still worthwhile!

I appriciate the comment, compliment, and I am glad to have enlightened you!