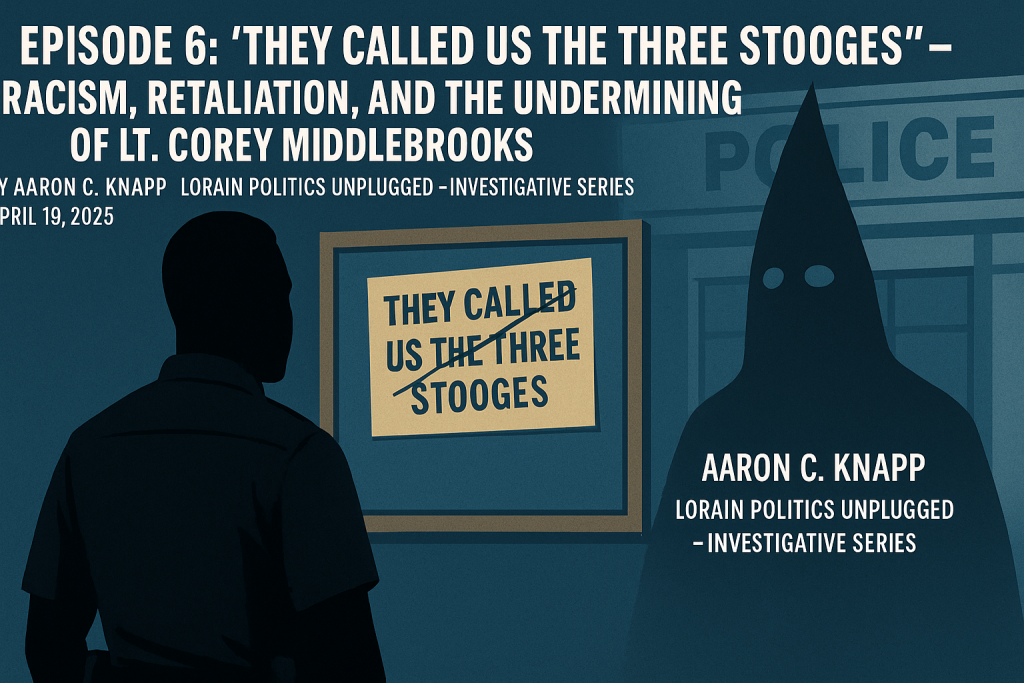

Episode 6: “They Called Us The Three Stooges” – Racism, Retaliation, and the Undermining of Lt. Corey Middlebrooks

By Aaron C. Knapp Lorain Politics Unplugged – Investigative Series

Apr 19, 2025

Introduction: The Pattern Deepens

In Episode 5, we exposed the political betrayal and racial sidelining of Officer Miguel Baez. Episode 6 continues the series by turning to Lt. Corey Middlebrooks, whose rise through the Lorain Police Department was as rapid as his fall was calculated. From being called a “stooge” on an internal department board to witnessing KKK placards inside the office of a superior, Middlebrooks’s story is not just about retaliation—it’s about institutionalized racism masquerading as discipline.

Lt. Corey Middlebrooks was once hailed as one of the department’s promising leaders. Promoted rapidly and known for his professionalism, he was among the few African American officers to achieve rank. But his career trajectory began to sour when he started asking uncomfortable questions—about hiring disparities, about retaliatory investigations, and about workplace hostility. His concerns, like those of Officer Baez, were met not with accountability, but with silence and sabotage.

The Lorain Police Department’s internal affairs investigation, spearheaded by Officer Kyle Gelenius, documents over 400 pages of testimony, contradictions, deflections, and disturbing admissions.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

At the center of it all stands Chief James McCann, whose actions and inactions raise profound questions about racial equity, workplace ethics, and leadership integrity within Lorain’s law enforcement community.

This episode dissects a key part of that testimony: Middlebrooks’s experience with racist symbols in police offices, the deliberate undermining of his authority, and a culture that tolerates bigotry behind closed doors.

The KKK Placards in the Captain’s Office

Perhaps the most damning revelation in the investigation was Lt. Corey Middlebrooks’s account of encountering Ku Klux Klan placards hanging on the wall inside a captain’s office. The incident, which occurred early in his career during a meeting about a minor uniform infraction, left a lasting scar. As he recalled during his Garrity interview, he walked into a meeting expecting routine discipline and instead found racist imagery staring back at him.

Middlebrooks described the scene vividly: a disciplinary meeting with fellow officers Arce and Baez. He sat down, glanced at the wall, and saw what he would later describe as “two placards, KKK signs.” He remembers thinking, “What the hell is that?” No one offered an explanation. No one acknowledged their presence. And when he raised the issue, the meeting abruptly ended. That silence, that quiet brushing-aside of hate, was its own form of violence.

To be clear, the captain whose office housed those placards was never formally disciplined. According to Middlebrooks, he later confronted that superior, who justified the imagery as artifacts from assisting another department during a Klan rally. But no one warned Middlebrooks of their presence. No one offered context until months later. And the investigation concluded that the department did not pursue a formal inquiry into how or why the placards were displayed.

Middlebrooks wasn’t alone in this experience. He claimed that fellow officers, including Baez, witnessed the incident. The lack of institutional response not only dehumanized him in the moment but affirmed a deeper message: that certain symbols and slurs were permissible—even inside city buildings—if they were old enough, ambiguous enough, or politically inconvenient to confront.

The KKK placard incident, never formally addressed in the chain of command, became a turning point for Middlebrooks. From that day forward, he began to see how racial tropes, coded language, and performative tolerance were embedded within the DNA of the department. It wasn’t just a bad day. It was a warning.

The “Three Stooges” and Public Ridicule

Following the placard incident, things only escalated.

At one point, someone had written on a department bulletin board the phrase: “The Three Stooges – Middlebrooks, Arce, and Baez.” All three were officers of color. Middlebrooks described the humiliation of walking into work and seeing himself reduced to a punchline.

He brought his concerns to Sgt. Ryan, his supervisor, and was told a meeting would be arranged with McCann to address the incident.

But instead of healing, the meeting only deepened his frustration. Middlebrooks said McCann failed to acknowledge the significance of the ridicule. He never condemned the racial connotation. Instead, the behavior was chalked up to “locker room culture” or ignored entirely. The meeting ended with nothing resolved, leaving Middlebrooks to navigate a department culture where bigotry could masquerade as banter.

This wasn’t an isolated incident. The phrase “Three Stooges” circulated among the ranks and became shorthand for dismissing officers of color. The systemic nature of the ridicule wasn’t lost on Middlebrooks. He observed that white officers who made mistakes were given private corrections or informal mentorship. Officers of color, meanwhile, were humiliated publicly and disciplined formally.

That disparity in treatment fueled Middlebrooks’s growing belief that the department was not just broken but fundamentally biased. It wasn’t about one captain or one placard. It was about patterns: who got called in, who got let off, and who got hung out to dry. He began to record incidents, save emails, and document disparities. The result would eventually form the basis of his EEOC complaint.

As we saw with Officer Baez, public ridicule in Lorain isn’t just about jokes. It’s a tool of marginalization. And like Baez, Middlebrooks was forced to continue working in an environment where his dignity was a punchline and his concerns were “overreactions.”

“They Called Us the Three Stooges” wasn’t just a joke—it was a racial slight. All three officers labeled this way were men of color: Lt. Corey Middlebrooks, Officer Miguel Baez, and Officer Arce. In a department that ignored KKK placards on office walls, this public mockery wasn’t harmless banter—it was a message. A way to undermine, diminish, and dismiss minority officers who spoke out. Racism doesn’t always wear a hood. Sometimes it hides behind a whiteboard and a smirk.

The Smile Comment and the “White’s Only” Remark

Two of the most offensive incidents Middlebrooks reported involved direct comments allegedly made by Chief McCann.

The first came during a moment when McCann allegedly told Middlebrooks, “Smile so I can see you,” when the lights were dimmed. Middlebrooks recalled being deeply offended. When pressed by OPS about whether it could have been a joke, he said, “Maybe to him. Not to me.”

Another incident involved Middlebrooks walking into Captain Watkins’s office, only to hear McCann say, “White’s only.”

Middlebrooks recounted the moment with discomfort, saying he immediately called his wife, who convinced him not to escalate the matter. It was a moment he now regrets letting go, describing it as a “mistake” that still weighs on him.

Both comments—if true—reveal an alarming level of normalized racism within the department’s leadership. McCann allegedly felt comfortable enough to make such remarks in front of peers and subordinates. And even when those present were visibly uncomfortable, like Captain Watkins, no formal objection was raised.

OPS investigators repeatedly asked Middlebrooks why he failed to report these incidents at the time.

His answer echoed that of many who suffer workplace discrimination: he feared retaliation. He wanted his work to speak for itself. He didn’t want to be “that guy”—the one always crying racism. But in staying silent, he became easier to target.

The result was a steady erosion of his authority and an environment in which he was both visible and invisible. Visible when mistakes could be highlighted. Invisible when success, mentorship, or fairness were on the table.

A Climate of Gaslighting and Contradiction

The internal affairs investigation into Middlebrooks was not just adversarial; it bordered on accusatory gaslighting. When asked for specific proof that McCann had lied about payroll changes or training decisions, Middlebrooks was often unable to produce documents. Yet, the totality of his experience—conflicting directives, selective enforcement, ridicule, and unequal treatment—pointed to something deeper than bureaucratic dysfunction.

OPS frequently challenged Middlebrooks’s memory and intent. Investigators accused him of being evasive, of exaggerating events, of being inconsistent. He was repeatedly asked why he included details in his EEOC complaint that he couldn’t definitively prove. But the question investigators rarely asked was: why would a Black officer fabricate a complaint that could end his career, if not rooted in real, lived disparity?

Middlebrooks wasn’t perfect. He admitted confusion over payroll. He struggled to explain why he didn’t always follow up.

But his imperfections became the department’s weapon. Each minor lapse was magnified into a character flaw. Each contradiction was treated as intent to deceive. OPS focused on holes in his story but ignored the crater in the culture.

McCann, by contrast, was never placed under the same scrutiny. Despite multiple officers, including Baez, raising concerns about his behavior, McCann remained insulated. He denied racial animus and accused Middlebrooks of filing “knowingly false” claims. OPS didn’t press him with the same rigor.

The entire process reeked of imbalance. It was as if Middlebrooks, not the alleged behavior, was on trial. And in Lorain, that imbalance has become standard operating procedure.

Conclusion: The System Protects Itself

As someone who relocated from the West Coast to Lorain, I did not expect to encounter this level of deep-seated racism within government institutions.

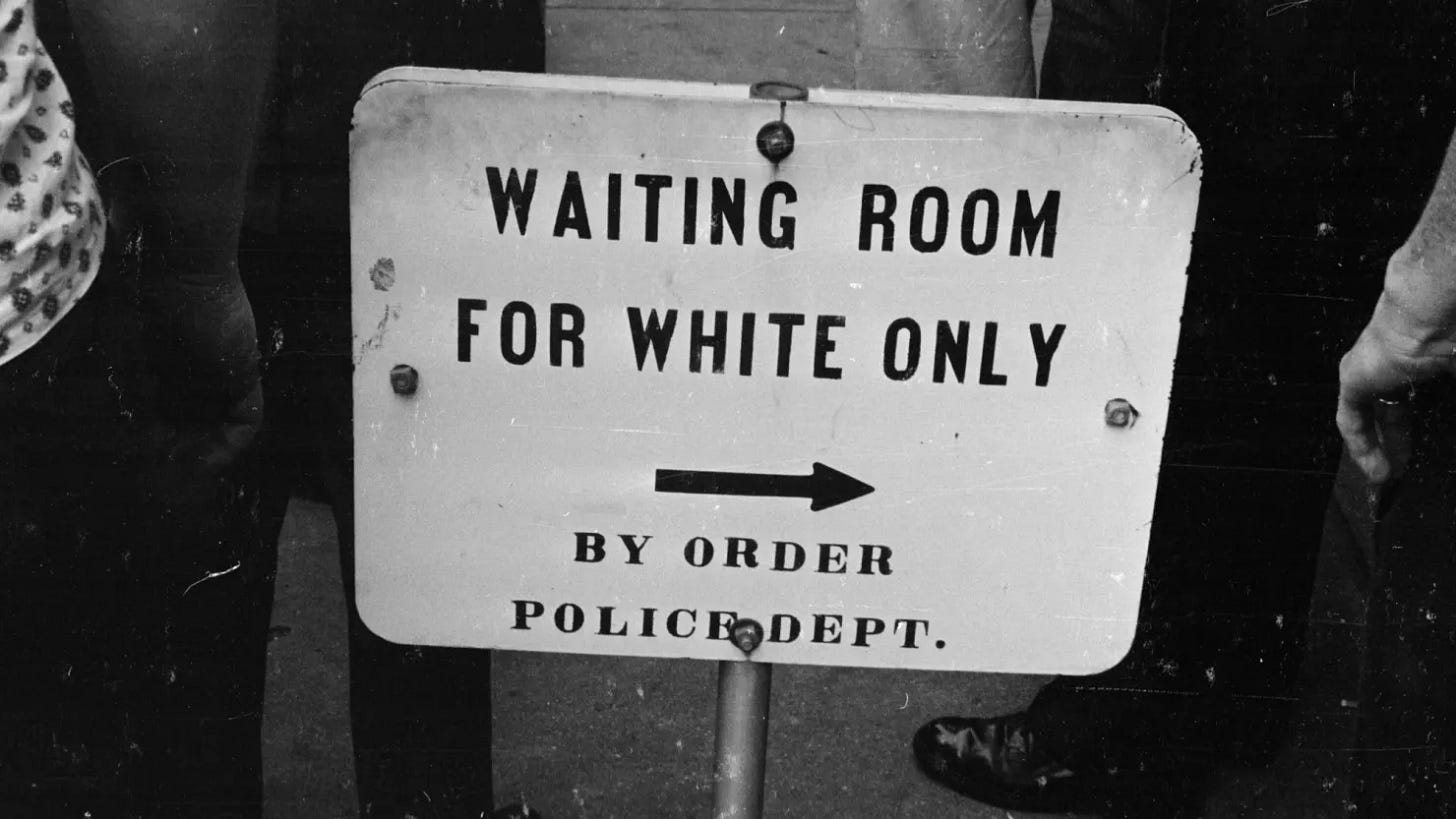

I grew up believing the symbols of white supremacy—the KKK hoods, the segregationist phrases, the mocking of Black skin tones—were artifacts of a hateful past. I was wrong.

Those artifacts are alive here. They hang on office walls. They get chalked up as harmless relics. They become part of the wallpaper of a city that would rather deny than reckon. What happened to Corey Middlebrooks is not just the failure of one department or one investigation. It is the deliberate rot of a system designed to silence, discredit, and exclude anyone who dares challenge the status quo.

McCann should be held accountable. So should every officer and administrator who ignored the signs, laughed off the jokes, or chose comfort over conscience. Middlebrooks’s career was not derailed because he failed. It was derailed because he succeeded in a place that only pretends to reward merit when the color is white…ohh wait..they meant right..

This city must decide whether it stands for justice or just its reflection. Because in Lorain, if your skin is dark and your spine is straight, the halls of power will do everything to bend you.

We will not let that go unanswered.

If you have experienced discrimination or retaliation within Lorain law enforcement, email aaronthesocialworker@gmail.com. All tips confidential.