Episode 6: The ERA Exchange

Credit Channel 5

Misconduct, Money, and Manipulation: How ERA Funds Became Bargaining Chips

May 03, 2025

By Aaron Knapp | Lorain Politics Unplugged

⚡️ Legal Disclaimer: All quotes are taken directly from the sworn depositions of Michelle Hung, JD Tomlinson, Dan Petticord, Dave Moore, and other public officials. Verified exhibits, requisition records, and court filings are used to establish the facts.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I. Correction, Context, and the Quiet Setup

Before diving deeper into the tangled web of political favors and public money in Lorain County, it’s important to correct a detail from Episode 5: The Chain of Command. That story incorrectly described KC Saunders as the County Administrator. In fact, Saunders is the Budget Director, also known as the Fiscal Director—not the administrator. While the correction may seem minor, understanding who wields what authority is critical to following the money, and, in this case, tracing it back to a quiet political arrangement that may have shaped the entire Battistelli settlement.

This story begins where the last one left off: with Commissioner Dave Moore voting to approve a $100,000 payment to former County employee Jennifer Battistelli—a payment pushed through as a requisition and disguised as a routine legal expense. The requisition was approved in October 2023, without ever publicly acknowledging the existence of a federal EEOC complaint alleging sexual misconduct by then-Prosecutor JD Tomlinson.

Sworn depositions show that Moore had knowledge of the complaint well before it was brought to a vote. Battistelli, in her statement to the Sheriff’s Office, claimed that JD Tomlinson told her, “You have to talk to Dave,” referring to Moore as the key player who would make the payout happen. At that point, Moore’s influence wasn’t just bureaucratic—it was political leverage.

What wasn’t known at the time was what Moore may have received in exchange. But now, a paper trail, combined with his own sworn testimony, suggests something even more damning: Moore quietly secured a letter of legal cover—in January 2024—from former Judge James Burge, stating that Moore’s acceptance of over $15,000 in Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds for his own rental properties in 2021 was lawful. That letter only materialized after the Battistelli requisition was approved.

In his own deposition, Moore claimed he received verbal approval from Dan Petticord to vote on and receive the ERA funds back in 2021. Petticord denies ever giving that approval. “I never gave that verbal authorization,” Petticord said. Judge Burge, under oath, also stated that the first time he even became aware of the ERA situation was in January 2024—long after the payments had been made, and notably after the Battistelli requisition had been quietly pushed through.

This timeline has become a cornerstone of the investigation. If Moore needed a legal cover letter to protect his own interests—and that letter came after the Battistelli payout—it raises one damning question: Was this a quid pro quo? Did Moore greenlight a secret $100,000 settlement to protect JD Tomlinson in exchange for Tomlinson protecting Moore’s financial liability?

The appearance of a trade-off is difficult to ignore. Especially when you consider that the ERA letter could have—and should have—come from the County Prosecutor’s Office in 2021. But it didn’t. Instead, it was cobbled together three years later by a former judge acting as Chief of Staff, while the prosecutor was under scrutiny for a sex-for-job scandal.

In his deposition, Moore never offers a convincing explanation for the delay. “I asked for clarification,” he said vaguely, referring to the 2024 letter. But he could not explain why he needed written confirmation three years after the fact—unless he feared public exposure. At the same time, Petticord’s denial of ever giving Moore approval contradicts Moore’s timeline and undermines his defense.

This sets the stage for a broader examination of how public officials use requisitions, legal favors, and insider connections to insulate themselves from consequences—and how one man’s vote and silence may have been bought for a piece of paper written after the fact.

II. The Paper Shield

In sworn testimony, Commissioner Dave Moore repeatedly insisted that there was nothing improper about his acceptance of more than $15,000 in Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds during the COVID-19 pandemic. But the timing of a pivotal letter—drafted three years later by former Judge James Burge in January 2024—has become the clearest indicator yet that Moore knew he needed retroactive cover. “The letter just clarified everything,” Moore said during deposition. What he didn’t explain was why such clarification came after scrutiny over his vote on the Battistelli payout began to surface.

The sequence is impossible to ignore. In October 2023, Moore voted to approve a $100,000 payout to Jennifer Battistelli without public disclosure of the underlying EEOC complaint. Then, in January 2024, Moore secured a memo from Judge Burge affirming the legality of his earlier ERA application and vote. This memo was never publicly disclosed until demanded in litigation, and it was not written by the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office—an omission that, on its face, appears designed to avoid scrutiny.

Moore claimed in his deposition that he relied on a “verbal OK” from Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord back in 2021 before applying for the funds. But under oath, Petticord denied that such a conversation ever happened. “I don’t recall giving him any verbal approval,” Petticord testified. “That would not have been my place.” Judge Burge’s own testimony further contradicts Moore: “The first time I heard about the ERA funds issue was January 2024.” If Moore had nothing to hide, why did he wait three years for documentation?

The memo itself is remarkably vague. Burge’s letter, entered into evidence, does not cite any statute, ruling, or ethics opinion. Instead, it provides a sweeping assertion that Moore did nothing wrong by applying for, voting on, and receiving the funds. This stands in direct contrast to a prior Ohio Ethics Commission ruling—which stated that public officials cannot participate in votes from which they stand to benefit financially. The Ethics Commission forwarded the Moore complaint to the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office, but no action was taken. Why? Because the prosecutor was JD Tomlinson—the very man Moore had just protected by voting for the Battistelli settlement.

That interconnection deepens suspicion. Not only did Moore benefit from a belated legal memo, but the person who should have investigated him—Tomlinson—was the same person protected by Moore’s silence. In another context, this would be called witness tampering or obstruction of justice. In Lorain County, it was politics as usual.

The question remains: why didn’t Petticord draft the memo if he supposedly gave the original approval? Moore’s claim that he had a greenlight from Petticord crumbles under the fact that Petticord won’t back him up and Burge claims zero knowledge until 2024. That left Moore with only one fallback—having Burge, then serving as Tomlinson’s Chief of Staff, provide an ad hoc opinion. “I was never involved in that matter in 2021,” Burge testified, “and I never issued any opinion until asked to in January 2024.”

Such statements destroy any argument that Moore acted transparently. If the ERA application was legitimate, the process would have required Moore to abstain from voting on the distribution of those funds. Instead, he voted to allocate money that directly enriched his own real estate business—then backfilled the ethics approval three years later after political heat mounted.

Even more damning is that this paper shield—drafted by Burge—was only sought after the Battistelli payout was complete. Moore didn’t seek clarity when applying for the money, nor when voting to approve its distribution. He only needed cover when questions started being asked. That’s not caution—it’s consciousness of guilt.

Taken together, Moore’s deposition, the conflicting testimonies from Petticord and Burge, and the timeline of the ERA memo all point toward a strategic trade: silence and compliance on the Battistelli payout in exchange for political and legal insulation. This wasn’t about process—it was about preservation.

And it worked. At least for a while. Moore was never prosecuted. The Ethics Commission passed the baton. Tomlinson stonewalled public records. And Burge, now gone from office, claimed ignorance. But the paper trail is harder to erase. And in Lorain County, this memo may yet become the blueprint for how political deals are laundered under the guise of “clarification.”

III. ERA for Silence: The Quid Pro Quo

As the public began learning more about the $100,000 settlement paid to Jennifer Battistelli, another deal was quietly unfolding behind closed doors—one that appeared to benefit Commissioner Dave Moore directly. The timeline reveals what looks like a textbook quid pro quo: Moore’s vote in favor of a concealed sexual harassment settlement for former Prosecutor JD Tomlinson, followed shortly by a legal cover letter absolving Moore of wrongdoing in a separate ethical scandal involving federal rental assistance money.

In his sworn deposition, Moore insisted that his 2021 application for more than $15,000 in Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds—used to subsidize tenants in properties he personally owned—was above board. He claimed he had received “verbal approval” from Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord before applying and voting on the program. “I got a verbal go-ahead from Dan,” Moore said under oath. But Petticord flatly denied it. “I never gave Commissioner Moore that kind of approval,” he testified, adding, “That would have required a formal ethics review.”

Faced with Petticord’s denial, Moore needed an alternate way to retroactively justify his actions. That’s when former Judge James Burge entered the picture. In January 2024—just months after Moore voted to approve the Battistelli requisition—Burge, then acting as Chief of Staff to Prosecutor Tomlinson, issued a letter exonerating Moore from any ethics violations.

The timing alone raised eyebrows. According to Burge’s own deposition, “The first I heard of any ERA issue was in January 2024. Before that, I was unaware of Moore’s involvement.”

This directly contradicts Moore’s account. If Burge wasn’t even aware of the ERA issue until three years after the fact, and Petticord denies giving prior legal clearance, Moore’s defense collapses. Why wait until 2024 for a legal opinion about something that happened in 2021—unless Moore was trying to clean up a trail?

Even more problematic is the fact that the Ethics Commission had already weighed in on this issue in general terms. In rulings dating back to 2020, the Ohio Ethics Commission made clear that public officials cannot vote on or otherwise influence the allocation of funds from which they will directly benefit. The Commission received a complaint about Moore’s ERA participation and referred it to the Lorain County Prosecutor’s Office—led, at that time, by JD Tomlinson.

That’s where accountability died. No investigation followed. No charges were filed. Tomlinson had every reason to bury the complaint: Moore had just helped him make a politically explosive EEOC complaint disappear behind the smokescreen of a mischaracterized requisition. “I believe the legal counsel should have been separate,” Michelle Hung testified. “The prosecutor needed his own, and so did we. But that’s not what happened.”

The whole thing stinks of mutual protection. Moore got a letter. Tomlinson got silence. And Petticord, who should have acted as a firewall between them, instead played both sides. Though he denied giving Moore approval, he also never publicly corrected the record. “I just don’t recall,” he said, when asked if he ever clarified the ethics question for Moore or the board.

Even Burge’s memo was a masterpiece of vagueness. It didn’t cite any specific statute. It didn’t address the Ohio Ethics Commission’s advisory opinions. It simply said Moore was fine. That letter wasn’t an opinion—it was a political favor written after the damage was already done.

What makes it all worse is that Moore later sold the properties involved in the ERA funding to Duane Bremke, a man with whom he has a history of opaque real estate transactions. Bremke, notably, is the uncle-in-law of a sitting judge. “He offloaded the properties to avoid seizure if this blew up,” one source close to the matter alleged. “Restitution would’ve been on the table otherwise.”no official forfeiture was filed, but concerns about it were raised.

In any functional county government, this would be a scandal. But in Lorain County, it was business as usual—protected by silence, paper trails, and the absence of accountability. The true cost wasn’t just $100,000 to Battistelli. It was the erosion of public trust.

IV. ERA for Silence: The Quid Pro Quo

In sworn deposition, Dave Moore insisted that his vote to approve the $100,000 Battistelli settlement had nothing to do with his own legal vulnerabilities. Yet the circumstantial record paints a starkly different picture—one of political dealmaking cloaked in administrative procedure. The centerpiece of this exchange? Moore’s receipt of a memo in January 2024—months after the payout—that retroactively justified his acceptance of over $15,000 in Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds. This memo, written by former Judge James Burge, served no practical purpose unless Moore felt he needed cover. And that cover only became necessary when scrutiny began to build over the very payout he helped push through.

Moore claimed in deposition that the letter was simply a clarification. But the need for such clarification three years after the fact—and immediately after a controversial vote—raises the specter of a quid pro quo. Moore had known about the Battistelli situation since at least 2021. As reported in the 558-page Sheriff’s Office report, Battistelli stated JD Tomlinson told her “someone has to talk to Dave” about her payout—referring to Moore’s critical role in making the settlement happen. And Moore did just that: he voted to approve the payment, which was disguised under “services and supplies,” with no mention of the sexual harassment complaint it settled.

The quid pro quo became even clearer when Moore invoked a supposed verbal conversation with Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord in 2021. According to Moore, Petticord had told him he was permitted to apply for, vote on, and receive ERA funds—even though that would constitute a textbook ethics violation.

Petticord, however, flatly denied it under oath. “I never said that,” Petticord testified. “That kind of approval would have to be in writing, and it wasn’t.”

Burge, who authored the 2024 letter, told a different story. He testified that the first time he ever became aware of Moore’s ERA situation was in January 2024—long after the payments were made and the settlement was complete. If Petticord didn’t approve it, and Burge hadn’t heard of it until recently, then Moore had no legitimate authority to take the money. That left only one explanation: the memo was created after the fact to shield Moore from political or criminal consequences.

And who asked Burge to write it? Moore did. That alone raises red flags. As Chief of Staff to Prosecutor JD Tomlinson, Burge was not an independent legal authority—he was part of the very office whose credibility was damaged by the Battistelli complaint. Worse yet, Tomlinson, in a phone interview with The Chronicle-Telegram, downplayed the entire situation, saying, “There was no salacious conduct. No scandal.” But that stands in direct conflict with the EEOC filing and Hung’s summary of its contents: “The job was in exchange of money for sex.”

What’s most disturbing is that this transaction—Moore voting for a sexual misconduct payout, then receiving a letter of legal exoneration—happened entirely outside the public eye. There was no mention of the complaint on the meeting agenda. There was no discussion of ethics implications. And there was no consultation with the Ohio Ethics Commission after their earlier ruling had already made it clear: elected officials cannot vote on funds that benefit them.

By all appearances, Moore’s silence bought him legal insulation. And his vote protected Tomlinson from further public fallout. In another political context, this exchange would trigger investigations, audits, and possible indictments. In Lorain County, it went unchallenged—until now.

Even now, Moore continues to maintain there was nothing improper about his actions. “It was just a misunderstanding of procedure,” he said in his deposition. But that doesn’t explain the urgency to obtain a memo three years late. It doesn’t explain why Petticord wouldn’t vouch for him. And it doesn’t explain why Burge—long after leaving the bench—was the one asked to justify a conflict Petticord wanted no part of.

Hung, when asked whether she believed the timing of the letter and the payout were connected, didn’t mince words. “Yes,” she said. “It’s political. They helped each other out. And the public paid for it.”

The facts point in only one direction. The ERA letter wasn’t clarification—it was compensation. And Moore’s vote wasn’t just unethical. It was currency in a political trade that shielded power players from accountability while taxpayers footed the bill.

V. The Official Denial Arrives Just in Time

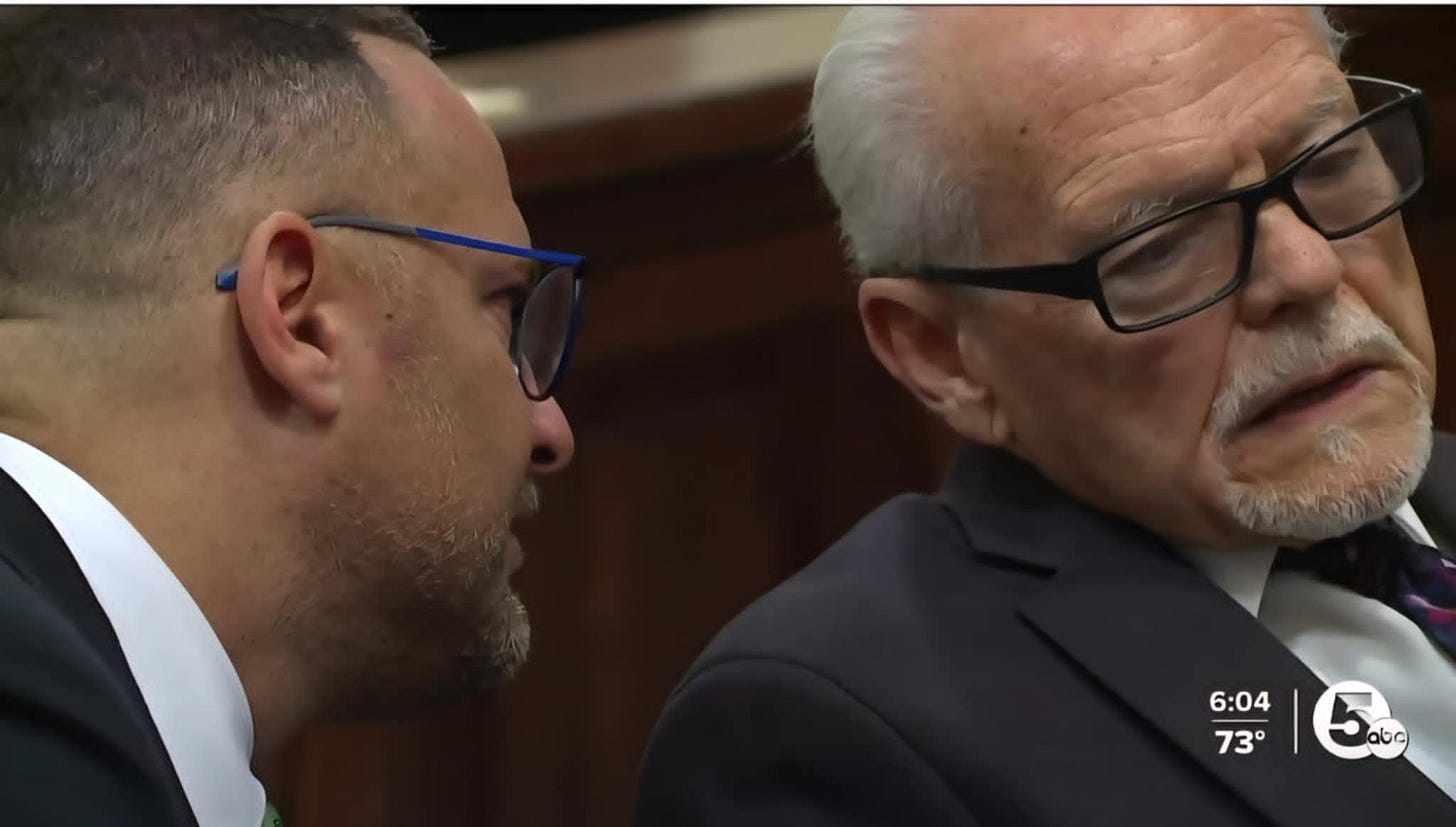

On February 23, 2024, just as public scrutiny reached a boiling point and News 5 Cleveland prepared to run its exposé, a curious letter surfaced. Signed by James M. Burge, Chief of Staff to outgoing Lorain County Prosecutor J.D. Tomlinson, the letter was addressed to Auditor Craig Snodgrass and asserted that no special prosecutor was needed to investigate Commissioner Dave Moore’s acceptance of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds.

The timing was impossible to ignore. The letter was released either the day before or the same day as the news report was set to air—and was shared widely by Moore’s political allies, including Loraine Ritchey. In effect, it was a preemptive PR maneuver, crafted not as a legal opinion from a neutral party but as a damage-control memo signed by Tomlinson’s own top aide.

“Commissioner Moore did not receive Emergency Rental Assistance Funds by reason of his public office,” the letter reads. “This relief is available to all eligible landlords/tenants simply by the application process.” Burge further wrote that “the law is settled” and, therefore, a special prosecutor was unwarranted. But nowhere in the letter did Burge address Moore’s vote on the ERA distribution—a direct conflict of interest under Ohio Ethics Commission precedent.

More importantly, this justification came more than two years after Moore applied for and received the funds—and just weeks after he had secured a retroactive letter from Burge himself, dated January 2024, validating the legality of Moore’s actions. As previously noted in Moore’s deposition, he claimed he had received verbal approval from Assistant Prosecutor Dan Petticord in 2021. Petticord, under oath, explicitly denied that ever happened. Burge, also under oath, said he had “no knowledge” of the ERA application until January 2024.

Yet this February 23 letter was circulated as if it closed the case. It ignored the ethical implications of Moore’s vote on funds he would personally receive. It glossed over the contradicting testimonies. It sidestepped the referral made by the Ohio Ethics Commission to the local prosecutor’s office—one that should have triggered, at minimum, an independent legal review.

So why issue the letter at all? Because Moore and his allies knew the walls were closing in. Channel 5 was preparing to air an investigative segment implicating Moore in the misuse of federal COVID relief funds, and they needed a shield. Instead of a transparent investigation, what the public got was a hasty memo—from a man already compromised by his involvement in other internal scandals.

“Normally, a special prosecutor is sought when there are facts that need to be discovered through investigation,” Burge wrote. “In this matter, the facts are known.” That sentence, far from offering clarity, only deepens the suspicion. The facts are not known—they’re actively in dispute. Petticord and Moore do not agree on the approval timeline. Burge only entered the picture after Moore’s potential exposure.

Even more troubling, this letter was never submitted to the Ohio Ethics Commission or presented as part of a public hearing. It was used exclusively to quiet critics and provide Moore a line of defense for media inquiries. This wasn’t a legal finding. It was a political smokescreen, timed with precision and backed by a shaky paper trail.

Had Moore’s use of ERA funds been fully lawful and ethical, none of this would have been necessary. He wouldn’t have needed a 2024 letter to justify a 2021 decision. He wouldn’t have had to rely on the memory of a conversation that two other public officials deny ever happened. In short, the letter was a bandage—applied too late and failing to stop the ethical hemorrhage.

With this memo, Moore and Tomlinson’s team tried to buy time and shift the narrative. But what they didn’t buy was public trust. Because when government officials only start answering questions after being exposed, what they’re really showing is guilt.

VI. Damage Control and the Ethics End Run

The story might have ended quietly—just another instance of public money quietly shuttled to those in power—but the unraveling began the moment the Battistelli settlement reached public attention. That unraveling exposed not only the quid pro quo between Dave Moore and JD Tomlinson, but also a coordinated effort to retroactively sanitize the entire operation.

On February 23, 2024, days before a Channel 5 news segment was scheduled to air, Moore released a letter authored by Jim Burge, then Chief of Staff to Prosecutor Tomlinson. The letter was addressed to County Auditor Craig Snodgrass and stated that a special prosecutor was not needed to investigate Moore’s receipt of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds. In Burge’s words: “Commissioner Moore did not receive Emergency Rental Assistance Funds by reason of his public office or by his using the influence of his public office to obtain these funds.”

The letter, notably, was not written by an independent investigator or ethics counsel. It was crafted by one of Tomlinson’s top aides—after Moore had already been publicly implicated in both the ERA conflict and the hush-money requisition to Battistelli. Worse, the letter’s timing suggests it was a calculated effort at damage control, aimed not at legal clarification but at media optics.

Ritchey, a local political commentator and frequent defender of Moore, posted the letter online the same day or the day before the Channel 5 news story aired. The timing appeared calculated—a preemptive strike meant to suggest official closure on a matter still under legitimate public and ethical scrutiny. The letter relied on a technical distinction: that ERA payments were issued to tenants, not landlords, and therefore Moore had not directly voted on his own financial benefit. But this legal framing clashed with the basic ethics test—and contradicted prior Ohio Ethics Commission guidance that any vote resulting in personal financial gain constitutes a conflict of interest.

Michelle Hung, in her sworn deposition, was incredulous that such a letter would be used as justification to avoid scrutiny. “That should have come from an ethics ruling, not from someone inside the prosecutor’s office trying to protect their boss,” she said. “There’s no independence in that assessment.” Hung’s concerns reflect a broader unease that political insiders were issuing exonerations to each other—without transparency, oversight, or legal basis.

The Burge letter also ignored a key piece of evidence: Moore did not simply receive funds, he applied for them while sitting as a county commissioner, then voted on budgetary items directly tied to their allocation. Even if the payment route was indirect, the result was direct personal enrichment. Moore collected over $15,000 in federal pandemic relief for properties he owned—then dumped those properties in a suspicious sale to real estate associate Duane Bremke just as the scrutiny heated up.

Even more damning, Burge’s memo was directly contradicted by his own earlier deposition. He previously testified that he had no knowledge of the ERA controversy until January 2024, when Moore requested the backdated opinion. The sudden shift—from ignorance to definitive legal opinion—suggests the letter was never about law. It was about providing political cover just in time for the headlines.

The fact that Burge’s February 23 letter was released the same week the Channel 5 story was poised to air adds weight to this theory. If the goal was transparency, the letter could’ve been issued months earlier. Instead, it functioned as a last-minute press kit—offering Moore a veneer of legality before the public found out what had been brewing behind the scenes.

The Lorain County Ethics Commission’s actual review of Moore’s actions—quietly referred by Columbus to Tomlinson’s own office—was never resolved in public view. Instead, it was buried under a stack of internal memos, conflicting testimonies, and carefully timed letters from friends in high places. To this day, Moore has never faced formal investigation, indictment, or sanction.

What the public got instead was a letter—not from a judge, not from the ethics commission, but from a political staffer employed by the very man Moore helped protect.

This wasn’t transparency. It was a containment strategy. And it nearly worked.

VII. Obstruction, Optics, and the Last-Ditch Letter

The last desperate attempt to salvage Commissioner Dave Moore’s reputation came not from transparency or accountability—but from timing. On the same day that WEWS NewsChannel 5 broke the story of Moore’s questionable acceptance of COVID-era Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds, a letter appeared. Moore released it publicly. The letter was also circulated by Loraine Ritchey, a vocal defender of Moore’s actions in public forums.. That letter—signed by former Judge James Burge—was supposed to serve as the firewall.

It didn’t.

The letter, dated January 2024, asserted that Moore’s actions in accepting over $15,000 in public rental funds while voting to allocate them were not improper. But the letter’s very existence raised more questions than it answered. Why was it issued three years after the vote? Why did it come from Burge, the Chief of Staff to Prosecutor JD Tomlinson, and not from the county’s own legal counsel at the time? And most damning: why was it only released after the scandal broke?

The timing spoke volumes. Moore released the Burge letter publicly just as news of the Battistelli payout hit Channel 5. Moore released it publicly. So did local blogger and frequent political commentator Loraine Ritchey, who had defended Moore’s conduct on social media. The damage was done, but the spin machine had already begun its work.

Moore’s defense, then, rests on a single memo drafted by a political confidant, devoid of legal precedent or ethics citations. It is not an opinion from the Ohio Ethics Commission. It is not backed by an ethics ruling. It is not corroborated by the prosecutor’s office. It is a desperate maneuver meant to create plausible deniability, but it collapses under the weight of its own contradictions.

What makes it worse is that the Burge memo was circulated only when public pressure mounted. Moore didn’t produce it when the ERA issue first arose. He didn’t reference it in any public meeting or commissioner records. He didn’t even share it when questioned in litigation—until it became clear the media was circling.

This is the pattern of Lorain County’s political defense apparatus: delay, deny, and deflect. First, deny the complaint exists. Then, deflect with backdated documents. Finally, delay the public release until a friendly press post can spin the story.

Moore’s strategy is clear. Moore released it publicly. So did local blogger and frequent political commentator Loraine Ritchey, who had defended Moore’s conduct on social media but the facts remain immutable: Moore voted on funds that benefited his personal business. He only sought cover years later. And the letter he clings to wasn’t worth the ink it was printed with.

The public isn’t stupid. They see through the optics. They understand that a legal letter produced in panic is not equivalent to a contemporaneous ethical clearance. They know that silence in the moment and noise in the aftermath is not transparency.

And now, with the record clear and the lies exposed, one question looms large: if Moore truly believed his actions were above board, why didn’t he say anything until a TV station did?

VIII. Final Thought: The Integrity Test Lorain Failed

Lorain County had a chance to hold the line on public integrity, but it failed the test. The ERA scandal, now wrapped tightly around Commissioner Dave Moore, is not simply about money—it’s about power, deception, and a deep betrayal of the public trust. From hidden EEOC complaints to backdated legal cover letters, from bogus verbal approvals to self-serving real estate transfers, every detail points to a culture of corruption masked by institutional silence.

It’s not just Moore’s actions that matter here—it’s the complicity of those around him. Petticord, who could have clarified the ethics of Moore’s ERA involvement in 2021, instead distanced himself after the fact. Judge Burge, Tomlinson’s Chief of Staff, conveniently produced a legal letter only after the payout to Battistelli was secured and public scrutiny loomed. JD Tomlinson himself—embroiled in a sexual misconduct complaint—was protected by a vote Moore cast, a vote that now appears to have been purchased with legal insulation.

The ERA letter should have come from Petticord or the Ethics Commission in 2021—not from a political ally trying to clean up a festering mess in 2024. The fact that Moore scrambled to release the letter only after news of the scandal broke on WEWS Channel 5 makes it worse, not better. That’s not transparency. That’s damage control.

Meanwhile, the properties Moore benefited from were offloaded to Duane Bremke—a longtime associate and, conveniently. That reeks of strategic laundering, not innocent real estate moves. Multiple sources close to the county government agree: Moore sold the assets to avoid potential seizure or restitution if this scandal ever blew wide open.

But it’s not just Moore and Tomlinson. This web of deceit includes Petticord, who is now reportedly working a cushy role at Job and Family Services, often absent, and still rumored to be advising politically powerful figures in the shadows. It includes those who chose not to question the requisitions, those who let EEOC complaints go unread, and those who remained silent while misconduct passed unpunished.

The public has every right to ask: How deep does this go? Why has no one been charged? Why did the Ethics Commission pass the complaint to the same prosecutor implicated in the scandal? These are not partisan questions. These are questions of law, ethics, and the very fabric of honest government.

And the truth is this: what happened with ERA funds was not an administrative oversight. It was a deliberate exchange. It was a quiet transaction of silence for security. It was a political deal in everything but name. And it makes every vote Moore has cast since then suspect.

To the voters of Lorain County: don’t let this pass quietly. These aren’t just bureaucratic errors. They are symptoms of a broken system. Demand accountability. Demand transparency. And demand that public office no longer be used as a shield for private gain.

Legal Disclaimer

This report is based entirely on verified public records, including sworn deposition transcripts from Dave Moore, Michelle Hung, JD Tomlinson, Dan Petticord, and others, as well as county requisition logs, public meeting minutes, budget documents, and internal emails entered into evidence. All quotes have been cross-referenced directly with the official transcripts and public filings.

This publication is intended solely for the purpose of investigative reporting, civic education, and public accountability under the protections of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. No part of this report should be construed as a legal determination of guilt or innocence, but rather as documentation of evidence and statements made under oath by public officials.

Coming Next: Episode 8 – “The Burge Doctrine”

What happens when a former judge becomes the fixer for a crumbling political alliance? In Episode 8, we dive into the dual role played by James Burge—once a Common Pleas Judge, now a behind-the-scenes architect of legal cover for embattled officials. From his role in crafting the ERA letter to shielding Tomlinson from scrutiny, we’ll dissect how Burge’s influence stretched from courtroom to county office.

Sworn depositions, internal emails, and new witness statements reveal how Burge rewrote timelines, backstopped lies, and may have crossed ethical lines to protect a failing inner circle.

The question is no longer just what happened—it’s who let it happen.

Subscribe to stay updated. Justice demands daylight.