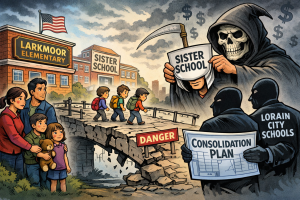

Austerity for Workers, Abundance for Power

Strike Outside the Seat of Power Caption for Article Use Frontline workers address the public during a labor strike, using amplified speech to demand sustainable wages and working conditions. While workers were told the cupboard was bare, the demonstration unfolded steps away from buildings and projects funded without hesitation. Photo Credit Photo courtesy of strike participants. Used for news and commentary purposes.

A strike, a script, and the machinery behind Lorain County’s austerity narrative

By Aaron Knapp

Investigative Journalist

Lorain Politics Unplugged

Introduction

The story Lorain County wants the public to absorb begins with restraint and ends with obedience. It begins with a familiar phrase that has long been used to quiet dissent and justify imbalance: every dollar starts in the taxpayer’s pocket. Government must be careful. Government must say no. This framing is not accidental and it is not new. It was deployed deliberately and publicly as Job and Family Services employees, represented by the UAW, moved toward a strike over wages, benefits, and working conditions they described as no longer sustainable.

But this dispute did not begin with a strike announcement. It did not begin with a press statement. And it did not begin this year.

I have been in contact with sources inside the Job and Family Services department going back to at least last summer. What they described then is what the public is only now being told: staffing strain that had become chronic, compensation structures that lagged far behind responsibility, and a growing sense that county leadership was not just ignoring the problem but actively insulating itself from its consequences. By the time workers reached the point of collective action, the pressure had been building quietly for months, if not years.

This was not a sudden breakdown. It was a slow one.

The demands made by Job and Family Services workers were not abstract. They were not ideological. They were not the product of political theater. These workers are the human infrastructure of Lorain County. They are the people who process food assistance and housing aid, who handle child protection cases, who manage crisis interventions, and who administer state and federal programs that determine whether families fall through the cracks or survive. They work inside systems where mistakes are measured in harm, not inconvenience.

Many of these employees earn modest salaries while carrying caseloads that would overwhelm most private sector operations. They navigate trauma daily. They absorb public frustration quietly. They keep programs running that politicians praise during press conferences and forget during budget negotiations. When they said the system was breaking, they were not speculating. They were reporting from inside it.

What made this crisis particularly stark, and particularly demoralizing, was the unequal way the county chose to respond to known problems.

As internal issues mounted, the county faced a benefits accrual problem that directly affected employee leave time. That problem was addressed, but not universally. Management level employees saw their accrual issues corrected. Non-management workers did not. In practical terms, this meant unequal time off, unequal relief from burnout, and unequal treatment under the same employer, even as leadership insisted there was no flexibility and no money to spare.

At the same time, conditions deteriorated to the point that a food pantry was established for county employees themselves. The people tasked with administering public assistance programs were quietly relying on mutual aid inside their own workplace. That fact alone should have triggered alarm and introspection at the highest levels of county government. Instead, it was treated as an inconvenience to be managed, not a warning to be heeded.

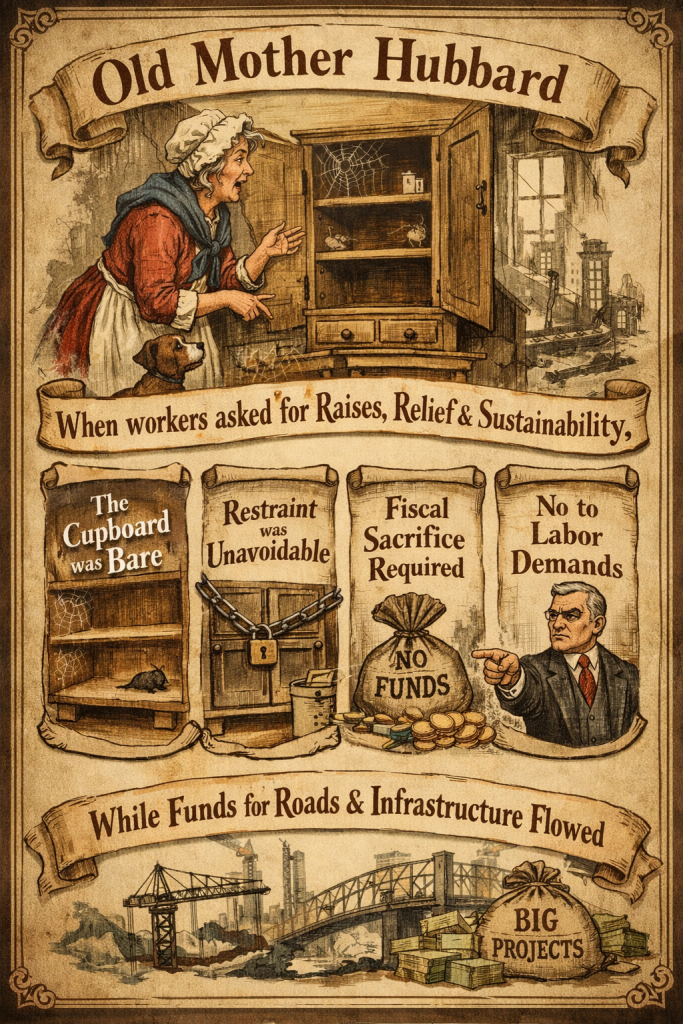

Rather than pause hiring, the county expanded management. Rather than rebalance compensation, it elevated administrative roles. While frontline workers were told to tighten their belts, high salary positions multiplied. Political allies were placed into positions of authority and influence. The structure grew heavier at the top even as the foundation strained beneath it.

By the time the county went public, the internal story was already written.

The county’s response was not to acknowledge this long-standing reality or to negotiate quietly. It was to go public and accusatory. Workers were framed as unreasonable. Their proposed raises were described as outrageous. Requests for flexibility were framed as entitlement. Healthcare costs were invoked without context, without shared responsibility, and without acknowledgment of management decisions that shaped those costs.

The message to workers and residents alike was simple and relentlessly repeated. There is no money. Asking for more is irresponsible. The county must protect taxpayers from excess.

That message was delivered with confidence, as if it were an objective fact rather than a political claim. It was delivered without reference to management expansion, consulting expenditures, or the structural decisions that had already committed the county to long-term financial obligations. It was delivered as a verdict, not an argument.

And it was delivered despite the fact that, when the county’s employment structure was examined by an independent auditor hired specifically to review it, the findings favored the workers’ position. Those findings were not embraced. They were dismissed.

That dismissal matters. Not because audits are infallible, but because rejecting independent review while invoking fiscal responsibility exposes a deeper posture. It suggests that austerity was not a conclusion reached through analysis, but a position chosen in advance.

That message is where this story begins. It is also where it immediately starts to unravel.

Because once the county chose to make this dispute public, once it chose to shame its workforce instead of leveling with it, the question stopped being whether there was money. The question became where the money goes, who decides, and why sacrifice is always demanded from the same people. The strike was the spark. The response was the tell. Everything that follows explains why this conflict was inevitable, and why it reaches far beyond a single department or a single contract.

The Video That Changed the Frame

As the labor dispute escalated and Job and Family Services workers moved closer to collective action, Lorain County Commissioner David J. Moore released a public video that fundamentally changed how the county wanted the conflict understood. It was not an update. It was not a status report. It was a reframing.

Moore did not speak to workers. He spoke over them, directly to taxpayers. Framed as a lesson in fiscal responsibility, the video cast the dispute as a moral contest rather than a labor negotiation. Moore warned viewers that Job and Family Services employees were demanding a twenty six percent increase over three years, requesting remote work accommodations, and seeking bonuses that the county allegedly could not afford. Each demand was presented in isolation, stripped of context, and delivered with a tone that suggested excess rather than necessity.

The posture mattered. Moore did not describe a complex budget problem. He described a discipline problem. His delivery was firm, measured, and paternal. The implication was unmistakable. County leadership was being forced to act as the adult in the room, protecting the public from irresponsible demands made by people who simply did not understand fiscal reality. This was not accidental language. It was calibrated. By addressing taxpayers instead of employees, the county moved the dispute out of the bargaining room and into the court of public opinion. By reducing months or years of internal strain to a handful of headline numbers, the county invited outrage rather than understanding. By emphasizing what workers wanted without explaining why they wanted it, the county positioned itself as the lone guardian of restraint.

What made the video consequential, however, was not just what Moore said. It was the ecosystem it revealed.

At the precise moment the county was insisting there was no money for frontline workers, a familiar figure from inside county operations appeared as part of the justification narrative. Not as a negotiator. Not as a neutral analyst. But as an authoritative voice reinforcing the county’s position.

That figure was Elise Aurvil.

Her appearance and role in this moment matters because it collapses the county’s public narrative and its internal reality into the same frame. Aurvil was not an outside consultant parachuted in to assess a problem. She was already embedded in county operations. She had functioned in an acting human resources role before being elevated into formal HR leadership. She was speaking not from a distance, but from inside a structure she helped administer. The video presented her participation as technical and neutral. In reality, it functioned as validation. Her presence signaled that the county’s position was not merely political, but managerial and professional. It suggested that the assessment of worker demands as unreasonable had been vetted, analyzed, and confirmed by human resources expertise.

That is where the frame changes. Because Aurvil’s role in county government did not exist in isolation. Before and during her ascent inside county administration, her private consulting entity had contracted with the county. She moved through the revolving door from outside contractor to internal authority in a system that was simultaneously expanding management, insulating decision makers, and invoking austerity when dealing with frontline staff. Her presence in the video did more than support Moore’s talking points. It tied the county’s labor posture to a broader pattern of internal alignment. The same leadership class that expanded management ranks, corrected benefits accrual issues for supervisors while leaving non management workers behind, and dismissed the findings of an independent auditor hired to review the employment structure was now presenting itself as the final arbiter of reason.

Seen in that light, the video was not about a raise. It was about legitimacy. By placing Moore front and center and surrounding the message with internal authority figures, the county attempted to close the conversation before it fully began. The implication was that the facts were already known, the analysis already done, and the outcome already justified. Workers were no longer participants in a negotiation. They were subjects of a lecture. This is the moment where the austerity narrative stops being about numbers and starts being about power. Because once the county chose to frame the dispute this way, every subsequent question became unavoidable. Who defines what is reasonable. Who benefits from management expansion while wages stagnate below. Who corrected their own benefits accrual while telling others to accept less. And who, precisely, gets to speak with authority when the county says there is no money.

The video did not resolve the dispute. It exposed the structure behind it.

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1AGYubLRuN

The Authority Behind the Message

Elise Aurvil did not appear in the county’s labor messaging by accident. Her presence in the county’s public posture toward its workforce was the product of a quiet but consequential transition inside Lorain County government. Before she became a central figure in county human resources, Aurvil operated through a private consulting entity that performed work for the county. That relationship placed her inside county operations while maintaining the formal distance of an outside contractor. It is a familiar arrangement in modern local government, one that allows expertise to be imported without the friction of civil service rules or internal promotion pathways. That distance did not last.

Aurvil moved from contractor into an acting human resources role and was later elevated into formal HR leadership. By the time the Job and Family Services dispute reached the public stage, she was no longer advising from the outside. She was part of the internal decision making structure responsible for personnel policy, benefit administration, and labor posture. That matters because the county was not merely negotiating a contract. It was defending a system. Human resources is not a neutral function during a labor dispute. It is the institutional voice that translates management priorities into policy, determines how benefits are structured, and frames what is deemed reasonable or excessive. When the county asserted that worker demands were unsustainable, it did so with the implicit backing of its HR apparatus.

Aurvil’s role gave that backing a face. Her appearance alongside the county’s public messaging signaled to the audience that the county’s claims had been vetted internally, that the numbers had been reviewed, and that the conclusions were grounded in professional judgment rather than political expedience. It suggested that the same structure responsible for administering benefits and managing employees had independently concluded that workers were asking for too much. But that framing collapses under scrutiny. At the same time county leadership insisted there was no flexibility, no money, and no alternative, the internal employment structure was under independent review. An outside auditor hired to examine the county’s employment and compensation framework found in favor of the workers’ position. Those findings were not adopted. They were dismissed.

That decision places human resources at the center of the story, not on its margins. Because if the county’s internal HR leadership rejected independent analysis while publicly reinforcing austerity talking points, then the issue is no longer disagreement. It is alignment. It raises the question of whether the HR function existed to assess conditions honestly or to defend decisions already made. That question becomes even sharper when viewed against the county’s treatment of benefits accrual. When accrual errors surfaced, the county corrected them for management level employees. Non management workers were left behind. The result was unequal leave time, unequal relief from burnout, and unequal treatment under the same employer. Those are not abstract policy choices. They are HR decisions with direct human consequences.

By the time workers were relying on a food pantry set up inside the county to supplement their own survival, the idea that this was a sudden or unforeseeable dispute had already collapsed. Aurvil’s presence in the county’s public messaging therefore does more than explain the county’s position. It anchors it. It ties the moral language of restraint to a specific administrative structure and a specific set of decisions. And that is where the story moves from rhetoric to network.

Because Aurvil’s role inside Lorain County does not exist in isolation. Her professional path, her consulting work, and her household ties connect outward into the same development, infrastructure, and influence ecosystem that repeatedly appears whenever the county insists it cannot afford to invest in its workforce.

That ecosystem is where this story goes next.

The Revolving Door Is Not a Metaphor

The transition that placed Elise Aurvil at the center of Lorain County’s labor posture was not abrupt, but it was decisive. It followed a familiar pattern in modern public administration, one that is often defended as efficiency and expertise but that carries real ethical risk when left unchecked. A private consultant works with a public body. Access is granted. Trust is built. Then the line between outside advisor and inside authority quietly dissolves. Before her elevation within county government, Aurvil operated through a private consulting entity that contracted with the county. That work placed her inside sensitive operational conversations while maintaining the formal distance of a vendor relationship. Consultants are not bound by the same internal constraints as employees. They are not subject to the same transparency expectations. Their influence is often informal, undocumented, and insulated from public scrutiny. When that consultant later becomes the official responsible for human resources, labor relations, and benefits administration, the transition deserves examination not because it is illegal on its face, but because it collapses safeguards that are supposed to exist by design. The county moves from being advised by an outside party to being governed by that same voice, now endowed with institutional authority.

By the time the Job and Family Services dispute became public, Aurvil was no longer offering recommendations. She was part of the decision making structure that defined the county’s negotiating posture, evaluated worker demands, and framed what would be presented to the public as reasonable or irresponsible. Her role gave managerial legitimacy to the county’s austerity claims at the precise moment those claims were being weaponized against frontline employees. That legitimacy matters because it was used to override independent scrutiny.

As internal pressure mounted, Lorain County retained an independent auditor to review the existing employment and compensation structure. This was not the county auditor and it was not a routine compliance exercise. It was an outside review commissioned specifically to assess whether the structure in place was sustainable and equitable. The findings supported the workers’ position. They validated what employees had been saying internally for months. The county did not adopt those findings. It dismissed them.

That decision reframes everything that followed. Once independent analysis is rejected, the issue is no longer uncertainty. It is preference. It signals that the outcome was determined in advance and that internal authority would be used to defend it, regardless of what external review revealed.

Human resources sits at the center of that choice. At the same time the county was telling workers there was no money and no flexibility, it was making selective corrections to its own systems. A benefits accrual issue surfaced that directly affected leave time. Management level employees saw their accruals corrected. Non management workers did not. The result was unequal time off, unequal recovery from burnout, and unequal treatment under the same employer. These are not theoretical disparities. They are measurable consequences of administrative decisions. As conditions worsened, the county quietly established a food pantry for its own employees. The people responsible for administering public assistance programs were relying on internal charity to get by. That reality alone should have forced a recalibration of priorities. Instead, it existed alongside continued management expansion and the elevation of high salary administrative roles.

This is the context in which Aurvil’s authority must be understood. Her role was not peripheral. It was central. She was part of a structure that corrected problems upward, dismissed independent findings downward, and then told workers to accept the result as fiscal necessity. The revolving door here is not symbolic. It is functional. It allowed the county to present austerity as professionalism. It allowed internal decisions to be defended as neutral expertise. And it allowed the same leadership class that expanded management and insulated itself from strain to claim that restraint was the only responsible option. But the story does not stop at county boundaries.

Aurvil’s professional position inside Lorain County intersects with a broader ecosystem of influence that includes economic development organizations, regional power brokers, and infrastructure projects that have consumed public attention and public money for years. Those connections do not prove wrongdoing. They do something more important. They show how authority, opportunity, and influence cluster around the same small network while workers are told there is nothing left.

To understand how the county could afford expansion, projects, and partnerships while pleading poverty at the bargaining table, you have to follow that network outward. That network leads next to Team NEO.

The Catalyst Moment

Aurvil’s presence in this dispute matters because she was not an outside commentator brought in to explain a budget spreadsheet or calm public nerves. She was already embedded in county operations in a way few members of the public fully understood at the time the dispute went public. By the time she appeared as part of the county’s justification narrative, she was not observing the system. She was part of it. Before becoming a county insider, Aurvil operated EHA Solutions, a private consulting firm that contracted with Lorain County to provide human resources related services. This was not a peripheral engagement. The scope of work placed her firm squarely inside the county’s personnel infrastructure, advising on matters that go to the core of how an employer treats its workforce.

The public record reflects that EHA Solutions functioned, in practice, as an internal HR authority. The firm advised on personnel policy, labor relations, and administrative restructuring. These are not clerical tasks. They are judgment heavy functions that shape compensation frameworks, benefits administration, discipline systems, and negotiating posture with employees. In effect, the county outsourced core human resources functions to a private entity while retaining formal distance from the decisions being made. That distance later disappeared. When Aurvil transitioned from contractor to acting human resources leadership and then into a formal county HR role, the authority she had exercised externally was absorbed directly into government. The same voice that had advised from the outside now carried institutional power on the inside. The county did not simply change vendors. It internalized the vendor.

This transition is not illegal by definition. But it is exactly the kind of revolving door that demands transparency, documentation, and scrutiny if the public is to have confidence in how decisions are made. When a consultant performs the work of an internal department and later becomes part of that department, the public has a right to know how that transition was handled, what safeguards were in place, whether competitive processes were followed, and whether any preferential treatment occurred. Those questions become even more urgent when the consultant turned official later appears as an authoritative voice in a public labor dispute, reinforcing claims that workers are asking for too much and that austerity is unavoidable. In this case, clarity was not forthcoming.

Instead of providing straightforward answers about the scope of EHA Solutions’ work, the timing of the transition, and the internal controls used to manage conflicts or continuity, the county responded to records requests with silence, delay, and resistance. Documents that would normally explain how authority moved from private hands into public office were not readily produced. The result was an information vacuum at the very moment transparency mattered most. That vacuum is not incidental. It matters because the labor dispute did not arise in a neutral administrative environment. It arose inside a system where independent audit findings favorable to workers were dismissed, where benefits accrual problems were corrected for management but not for non management staff, and where frontline employees were organizing mutual aid to survive while being told publicly that restraint was the only responsible option.

In that context, Aurvil’s trajectory from contractor to internal authority is not a side note. It is a catalyst.

It helps explain how the county could speak with such certainty while rejecting outside analysis. It helps explain how management priorities remained insulated while worker conditions deteriorated. And it helps explain why the county’s austerity narrative carried the tone of finality rather than negotiation. This moment is where the story moves decisively from a labor dispute to a systems question. Because once private authority is converted into public power without transparency, the issue is no longer just what decisions were made. It is who was positioned to make them, who benefited from continuity, and who was left without leverage when the county said there was no money. That question does not stop with human resources. It widens outward, into the same network of relationships, boards, projects, and partnerships that repeatedly surface whenever Lorain County’s priorities are examined. That is where this story goes next.

From Consultant to County Authority

By the time the UAW dispute erupted, Elise Aurvil was no longer operating at arm’s length from Lorain County. She was positioned as an internal authority, shaping how the county evaluated worker demands, defined fiscal constraints, and articulated human resources policy to both employees and the public. Her role was not advisory in the abstract. It was operational. It carried weight inside the very structure insisting that restraint was unavoidable. Workers were told there was no money. They were told to be reasonable. They were told to accept austerity as an economic fact rather than a choice.

That messaging carried the implicit assurance that it had been vetted internally, that professionals had reviewed the numbers, and that leadership had no alternative. Human resources functioned as the institutional validator of that claim. When the county spoke, it spoke with the confidence of settled analysis, not ongoing negotiation. But that confidence collapses when placed next to the county’s own compensation reality.

Payroll records show Lorain County maintaining and, in some areas, expanding six figure compensation for administrators, legal staff, command personnel, and senior leadership during the same period frontline workers were told the cupboard was bare. These were not legacy salaries frozen in time. They reflected an active compensation structure that continued to reward management and executive tiers even as the county publicly invoked austerity.

The restraint was selective. It flowed in one direction. This is not a philosophical disagreement about government size. It is a documented contradiction. When austerity is applied downward but never upward, it ceases to be a fiscal principle and becomes a management strategy. It signals whose stability matters and whose strain is considered acceptable. That contradiction becomes more troubling when viewed alongside Aurvil’s professional position and the network in which it sits. Her authority inside county government did not exist in isolation. It was built through a pathway that began with private consulting, moved through acting leadership, and culminated in formal control over human resources policy at a moment of acute labor conflict. The same structure that dismissed independent audit findings favorable to workers and corrected benefits problems for management but not for non management staff was now presenting its conclusions as final. And beyond the internal contradictions lies a broader web of relationships that places this moment in context.

Aurvil’s role intersects with an ecosystem of influence that extends beyond the HR office and beyond the labor dispute itself. It touches regional development organizations, long standing power brokers, and county priorities that have consistently found funding even when workers were told none existed. Understanding that network is essential to understanding how austerity became the default answer for employees while expansion and ambition continued elsewhere. This is the point where the story moves from internal policy to external alignment. Because once authority is consolidated internally and reinforced by a broader network of influence, the question is no longer whether the county could afford to treat its workers differently. The question becomes why it chose not to.That question leads next into the relationships and institutions that sit just outside county government but exert profound influence over its decisions.

The Private Network Behind Public Decisions

Any serious examination of how power operates in Lorain County has to move beyond formal titles and recorded votes. It has to examine proximity. It has to examine networks. And it has to examine how public authority intersects with private influence in ways that are entirely lawful on paper yet ethically consequential in practice.

Elise Aurvil is married to Steven M. Auvil, the Managing Partner of Squire Patton Boggs and Vice Chair of the Board of Team NEO. That fact alone does not establish wrongdoing. But it does establish something that cannot be ignored in a story about austerity, development, and decision making: the convergence of public administrative authority and private regional power within the same household.

Team NEO is not a casual civic organization or a ceremonial board appointment. It is the JobsOhio network partner for Northeast Ohio, positioning it at the center of the state’s economic development pipeline. Through that role, Team NEO helps coordinate business attraction, site selection, incentive alignment, and infrastructure prioritization across multiple counties. When Team NEO advances a project, it does so with the weight of state aligned economic strategy behind it. When it partners with local governments, money, land use decisions, and long term commitments often follow.

This is how modern development influence works. It is rarely crude or explicit. It does not require direct instruction or personal intervention. It operates through alignment. Through shared assumptions. Through overlapping boards, recurring partnerships, and an unspoken understanding of which projects are considered priorities and which are treated as constraints.

No one is alleging that Steven Auvil personally directed Lorain County decisions. That is not how influence in this ecosystem typically manifests. The ethical question is not whether a phone call was made or a meeting was held behind closed doors. The ethical question is whether the public can confidently say that private networks of power did not shape public outcomes in ways that were never openly debated. That question becomes unavoidable when austerity is invoked selectively. At the same time Lorain County told Job and Family Services workers there was no money, no flexibility, and no alternative, the county continued to participate in and pursue development strategies tied to regional economic networks. These strategies require planning, coordination, legal work, and administrative bandwidth. They require county cooperation and political will. They also require the same officials who invoke restraint at the bargaining table to commit public resources elsewhere.

When human resources authority sits inside a household connected to the region’s most influential development organization, the issue is not accusation. It is confidence. It is about whether the public can trust that decisions about workers, budgets, and priorities were made in an environment free from structural bias toward expansion, projects, and partnerships that benefit a narrow circle while austerity is imposed on those without leverage. This is why transparency matters more than intent. Public confidence does not depend on proving corruption. It depends on the ability to see clearly how decisions are made, who participates in shaping them, and whether safeguards exist to prevent undue influence. In Lorain County, those safeguards were not made visible. Independent audit findings were dismissed. Records requests were resisted. Authority consolidated internally while explanations were delivered externally.

Seen in that light, the labor dispute was not an isolated conflict. It was a stress test. And what it revealed was not just a disagreement over wages, but the outline of a system where public decisions are made within a private network of aligned power.

That network does not end with Team NEO. It extends into infrastructure priorities, long running development ambitions, and county entities designed to move money and land with limited public scrutiny. To understand why austerity became the county’s default answer to its workers, you have to follow that network further outward. That path leads next to the Port Authority, the Mega Site, and the choices Lorain County made about what it could afford and what it chose to fund anyway.

Team NEO and the County’s Priorities

Once the county’s internal labor posture is placed next to its external spending commitments, the austerity narrative begins to fracture. The same leadership insisting there was no money for frontline workers has repeatedly found resources, urgency, and political will when projects aligned with regional development priorities entered the picture. At the center of that alignment sits Team NEO. Team NEO’s fingerprints appear repeatedly on Lorain County’s largest and most ambitious spending decisions. Through its role as the JobsOhio network partner for Northeast Ohio, Team NEO functions as a coordinating hub for site development, infrastructure readiness, and business attraction. That role is not symbolic. It directly shapes which projects advance, which sites receive state attention, and which local governments are expected to commit resources to remain competitive.

The clearest example is the Northeast Ohio Mega Site near Lorain County Regional Airport. Lorain County partnered with JobsOhio and Team NEO to position nearly one thousand acres of land as shovel ready for large scale manufacturing. Doing so required massive public investment, particularly in water and sewer infrastructure capacity. These were not hypothetical future costs. They were immediate, concrete commitments made by the county in pursuit of long term economic development goals. Projects like the Mega Site are routinely justified in the language of fiscal responsibility and future growth. They are framed as investments rather than expenditures, as necessities rather than choices. But that framing obscures the reality that these initiatives demand significant upfront public spending. They generate consulting contracts, engineering work, environmental review, land acquisition, legal services, and ongoing governance obligations. Much of that activity flows through appointed boards, intermediary entities, and regional partners that operate largely outside the day to day visibility of voters. The contrast is stark. When frontline workers asked for relief from unsustainable conditions, they were told the county had no money and no flexibility. When regional development partners asked for infrastructure commitments measured in tens of millions, the county found a way.

That pattern does not stop at the Mega Site.

At the same time Lorain County was invoking austerity in labor negotiations, it was also pursuing mall purchases and redevelopment schemes through the Lorain County Port Authority. The Port Authority is not a minor player. It is a powerful vehicle for real estate acquisition, financing, bond issuance, and development partnerships. It is also structurally designed to operate at arm’s length from direct voter scrutiny. While commissioners appoint its board and influence its direction, the authority itself functions with a degree of insulation that makes public oversight more difficult. That design is not accidental. Port authorities exist to move quickly, assemble land, and structure deals that traditional government bodies might struggle to execute openly. But that same insulation creates risk when priorities are not evenly applied. When workers are told there is no money for wages or benefits, but millions can be mobilized for development schemes, the question becomes one of governance rather than economics.

The historical context matters here. The Lorain County Port Authority was created during David J. Moore’s earlier tenure as commissioner in the early two thousands. Its existence reflects a long standing county strategy that prioritizes development intermediaries as engines of growth. That strategy has persisted across administrations, shaping how resources are allocated and how decisions are justified.

None of this is inherently improper. Economic development is a legitimate function of county government. Infrastructure investment can be prudent. Port authorities can serve public purposes. The issue raised by the Job and Family Services dispute is not whether these tools should exist, but whether they have been allowed to dominate the county’s definition of responsibility. When fiscal discipline is invoked only at the bargaining table and never at the project announcement, it stops being discipline. It becomes narrative control. The county’s priorities are not hidden. They are visible in what it chooses to fund, what it chooses to expand, and what it chooses to defend. Team NEO aligned projects receive urgency, coordination, and political backing. Worker driven concerns receive lectures about restraint. That imbalance is the throughline of this story. Because when development ambitions and private regional networks consistently outrank the wellbeing of the workforce that keeps county government functioning, the issue is no longer a single dispute or a single contract. It is a values problem embedded in the county’s decision making structure.And that structure, once examined closely, raises the same question again and again. Not whether Lorain County had money, but what it decided money was for.

Boards, Towers, and Quiet Influence

The network does not stop with headline development projects or labor negotiations. It extends into the quieter institutional spaces where long term priorities are shaped and normalized long before the public ever sees a vote. This is where influence becomes durable, not because it is dramatic, but because it is embedded.

Team NEO operates inside a regional ecosystem that intersects with institutions such as Lorain County Community College. Leadership from LCCC has appeared on regional and local development boards, participating in the same planning and coordination circles that shape workforce pipelines, site readiness, and infrastructure priorities. These roles are not symbolic. Board participation is where consensus is formed, where projects are framed as inevitable, and where alternative paths quietly fall away.

That intersection matters because campus infrastructure, workforce development, and regional technology planning do not exist in silos. They routinely overlap with county decisions about communications systems, emergency services, and capital investments. When those conversations take place across appointed boards, consultants, and intermediary authorities rather than in open legislative forums, they move with less friction and far less public scrutiny. The county’s emergency radio system saga unfolded squarely within this environment. Tower siting decisions, infrastructure contracts, lease arrangements, and the eventual push toward statewide communications systems were all justified using the same language the county later deployed against its workforce. These decisions were framed as necessary, inevitable, and fiscally prudent. The public was told there was no real choice. The systems were outdated. The transition was unavoidable. The costs were the price of modern governance.

Yet those choices involved tens of millions of dollars in commitments, including duplicated infrastructure, consulting contracts, legal exposure, and long term operational obligations. They were not marginal expenditures. They were structural decisions that reshaped how the county communicates, who controls key assets, and how future options are constrained. What makes this relevant to the labor dispute is not the subject matter. It is the method. When infrastructure projects and system transitions aligned with regional priorities and institutional consensus, fiscal caution disappeared. Urgency replaced deliberation. Expenditure was framed as investment. Risk was treated as acceptable. Oversight was diffused across authorities designed to operate at arm’s length from direct voter accountability.

When frontline workers asked for raises, relief, and sustainability, the language changed instantly. They were told the cupboard was bare. They were told restraint was unavoidable. They were told that fiscal responsibility required sacrifice. The same officials who accepted inevitability in infrastructure spending insisted on immovability in labor negotiations.

This is the quiet influence at the heart of the story.

It is not about a single board seat or a single decision. It is about how priorities are set in practice. When the same network of regional partners, institutional leaders, and appointed authorities repeatedly converges around projects deemed essential, those projects move forward with speed and confidence. When workers raise alarms about the system’s human cost, their concerns are treated as discretionary.

Boards, towers, and systems may seem distant from a bargaining table. In reality, they reveal the county’s operating logic. They show how money is found, how urgency is constructed, and how certain commitments are shielded from the scrutiny applied to others. Once that pattern is visible, the county’s claim of austerity no longer reads as neutral accounting. It reads as choice. And it raises the unavoidable question that threads through every part of this story: not whether Lorain County had money, but why it consistently chose to spend it everywhere except on the people holding the system together.

The Audit They Did Not Want

Perhaps the most revealing contradiction did not come from a press release or a campaign style video. It came from an audit the county itself chose to commission and then chose to ignore.This was not the Lorain County Auditor performing a routine statutory review. It was an independent auditor retained to examine the county’s existing employment and compensation structure in the face of mounting internal strain. The purpose of the review was clear. It was meant to test whether the system the county was defending was actually sustainable, equitable, and defensible under objective analysis. The findings did not align with the county’s preferred narrative. The independent audit raised concerns that validated what Job and Family Services workers had been reporting internally for months. It identified structural problems, compensation issues, and management decisions that supported the workers’ claim that the system was not merely tight, but broken. In other words, when the county finally subjected its posture to outside scrutiny, that scrutiny did not confirm austerity as necessity. It challenged it.

The commissioners’ response was not reform. They rejected the audit. They dismissed its conclusions publicly. They treated independent analysis as an inconvenience rather than a safeguard. That choice matters more than the findings themselves. Audits exist for a reason. They are designed to test claims of fiscal responsibility, not affirm them automatically. They exist to introduce evidence into systems that are otherwise dominated by internal consensus and political messaging. When leadership commissions an independent review and then discards it because the results are inconvenient, the issue is no longer disagreement. It is control.

Rejecting an independent audit while simultaneously lecturing workers about budget discipline is not neutral governance. It is a declaration that evidence will be accepted only when it reinforces decisions already made. It tells employees that their lived experience will be discounted. It tells taxpayers that transparency is conditional.Placed alongside everything else, the pattern becomes unmistakable.

When workers organized mutual aid to survive, the county offered lectures.

When benefits accrual problems affected management, they were fixed.

When the same problems affected non-management workers, they were not.

When independent auditors validated worker concerns, the findings were dismissed.

When development projects demanded millions, money appeared.

When labor demanded sustainability, austerity was invoked.

This is why the audit is not a footnote. It is a turning point. It shows that the county did not merely miscalculate. It chose not to know. And when knowing became unavoidable, it chose not to listen. At that point, the story stops being about a contract dispute or a budget shortfall. It becomes a question of governance culture. Who gets believed. Who gets protected. And who gets told, again and again, that there is no money. The answer to those questions is written not in rhetoric, but in the decisions the county made when faced with evidence it could not spin away.

What the Pattern Shows

When these elements are viewed together, the dispute over Job and Family Services wages stops looking like an isolated labor conflict and starts reading like a case study in how power actually functions in Lorain County. Frontline workers are told there is no money. That message is delivered repeatedly and with confidence. It is framed as economic fact rather than policy choice. At the same time, executive compensation continues without interruption. Six figure salaries remain intact. New management roles are created. Legal and administrative positions are protected. The austerity narrative does not travel upward. Consultants are paid. Outside expertise is retained. Legal strategies are pursued even when they generate predictable costs and exposure. Development plans move forward with urgency and political backing. Infrastructure investments measured in the tens of millions are treated as necessary, inevitable, and prudent. When the subject is projects, the county finds flexibility. When the subject is people, it finds limits.

Boards and authorities play a central role in making this possible. Entities controlled by appointment rather than election steer land, infrastructure, financing, and contracts. These bodies operate with legal authority but reduced visibility. Their decisions shape long term obligations without requiring the same level of public debate or accountability that accompanies direct legislative action. This structure is not hidden. It is normalized. And it consistently channels resources toward development ambitions rather than workforce stability. Private networks sit adjacent to public power throughout this system. Influence does not need to be explicit to be effective. It flows through overlapping boards, shared priorities, and aligned institutional goals. Regional development organizations, educational institutions, legal firms, and county leadership occupy the same planning space. Consensus is built quietly. Alternatives are framed as unrealistic. Once a path is defined, it becomes difficult to question without being cast as obstructionist. When that consensus is challenged with evidence, the response is revealing.

Independent audits that contradict the county’s preferred narrative are rejected. Findings that validate worker concerns are dismissed. Transparency is treated as optional. Records requests are resisted. Litigation is chosen over disclosure even when the outcome is predictable and costly. The system defends itself not by engaging with criticism, but by narrowing the range of acceptable facts. Taken together, these are not disconnected events. They are reinforcing mechanisms.The same governance culture that dismisses worker testimony also dismisses independent analysis. The same leadership that invokes restraint at the bargaining table authorizes expansion elsewhere. The same officials who claim fiscal discipline reject audits designed to test it. The same structures that insulate development decisions from public scrutiny are used to justify why worker demands are nonnegotiable. This is not one scandal. It is an ecosystem. It is a system that rewards alignment and punishes disruption. A system where authority consolidates quietly and accountability is treated as an inconvenience. A system where austerity is not an economic condition, but a narrative tool deployed selectively to maintain control. Understanding that pattern does not require proving criminal conduct. It requires paying attention to who is believed, who is protected, and who is told to accept less. It requires comparing what the county says it cannot afford with what it repeatedly chooses to fund. Once that comparison is made honestly, the conclusion becomes unavoidable. Lorain County’s problem is not a lack of money. It is a lack of balance, transparency, and willingness to apply the same standards to power that it applies to workers.

The Corruption Question

Corruption does not usually arrive with a brown envelope or a criminal indictment. In modern governance, it is more subtle and far more durable. It appears as a system that consistently benefits the same circles of influence while distributing sacrifice downward. It presents itself as professionalism, inevitability, and fiscal prudence. And it survives precisely because it rarely violates the law in obvious ways. Nepotism today is rarely the blunt hiring of a relative into a visible public job. It is structural. It is influence that clears pathways rather than opening doors. It is access that normalizes exceptions, accelerates approvals, and ensures that certain people and priorities are never subjected to the same scrutiny imposed on everyone else. It is a governance culture where relationships matter more than process, and where outcomes are shaped long before the public is told a decision is unavoidable.

Ohio law recognizes this reality, which is why it does not limit corruption to overt acts. Ohio Revised Code 2921.42, which governs unlawful interest in a public contract, is written broadly for a reason. It is meant to capture not just direct financial self dealing, but situations where public authority intersects with private benefit in ways that undermine confidence in impartial decision making. Employment itself can constitute a public contract under Ohio law. So can consulting arrangements, advisory roles, and indirect financial interests that are definite and direct.Similarly, Ohio Revised Code 102.03 exists to address influence that may not be criminal on its face but is corrosive to public trust. It prohibits a public official or employee from using the authority or influence of office to secure anything of value, and it bars actions that would result in a substantial and improper influence. “Anything of value” is intentionally broad. It includes not only money, but opportunities, positions, advantages, and favorable treatment that flow from proximity to power.

These statutes exist because the damage of corruption is not limited to the moment a law is broken. The real damage occurs when the public comes to believe that outcomes are predetermined, that evidence is optional, and that accountability applies only to those without leverage.Viewed through that lens, the question raised by Lorain County’s recent history is not whether a single official crossed a bright legal line. The question is whether the system as a whole has been structured in a way that predictably favors insiders while demanding restraint, patience, and sacrifice from workers and residents who lack access to the same networks. When a county elevates consultants into internal authority without transparency, dismisses independent audits that challenge its narrative, corrects benefits problems for management but not for frontline staff, expands administrative compensation while invoking austerity, and advances development projects through appointed bodies insulated from voters, the issue is no longer coincidence. It is design.

No one needs to prove a bribe to ask whether this design serves the public. No one needs to allege a phone call to question whether private networks have shaped public outcomes. The ethical threshold is lower than the criminal one for a reason. Public trust depends not on the absence of indictments, but on the presence of fairness, openness, and equal application of standards. This is where the corruption question actually lives. It lives in whether Lorain County applied the same rigor to itself that it applied to its workers. It lives in whether evidence was welcomed or rejected based on convenience. It lives in whether authority was exercised to serve the public broadly or to protect a narrow ecosystem of influence. And once that question is asked honestly, the answer does not depend on speculation. It depends on the record the county itself created.

Why the Workers Matter Most

The UAW represented Job and Family Services workers were not simply bargaining for higher pay. They were exposing a moral contradiction at the center of Lorain County governance. Their demands forced a comparison the county did not want made. A government that can finance mega sites, pursue mall acquisitions, absorb consulting fees, expand administrative ranks, and commit to long term infrastructure projects is not operating under unavoidable scarcity. It is making choices.

These workers sit at the most unforgiving intersection of policy and reality. They are responsible for administering the social safety net that county leadership invokes rhetorically but too often neglects materially. They manage benefit eligibility, child welfare cases, crisis interventions, and compliance with state and federal mandates that carry real consequences when they fail. Their work does not produce ribbon cuttings. It produces stability. When it breaks, the harm is immediate and human.

What the workers’ action revealed is not just a compensation dispute, but a values test. A county that insists there is no money for the people doing this work, while repeatedly finding resources for development ambitions and administrative insulation, is not constrained by finances. It is constrained by priorities. When leadership chooses to lecture workers publicly, to frame them as unreasonable, and to portray their demands as threats to taxpayers, it is choosing narrative control over accountability.

That choice is especially telling given everything that sits alongside it. Independent audit findings that favored workers were dismissed. Benefits problems were corrected for management but not for non management staff. Employees organized mutual aid to survive while being told austerity was responsible governance. At the same time, the county sustained a web of insider relationships, appointed boards, and high dollar projects that never seemed to encounter the same limits. This is why the workers matter most in this story. They did not create the ecosystem of influence that surrounds county decision making. They did not design the development pipeline, appoint the boards, or normalize the idea that some expenditures are inevitable while others are indulgent. What they did was make that ecosystem visible by refusing to absorb its costs silently. When workers insist on dignity and sustainability, they are not just negotiating a contract. They are asking whether the system they serve is willing to meet its own standards. When the answer to that question is deflection, dismissal, and public shaming, the issue stops being labor relations and becomes governance integrity. The workers did not expose corruption by alleging crimes. They exposed it by forcing a simple, unavoidable comparison. What the county says it cannot afford versus what it repeatedly chooses to fund. Once that comparison is made honestly, the argument collapses. Not because of ideology. Because of evidence. And because in the end, a government that cannot bring itself to fairly support the people who keep its most essential services running is not suffering from a budget crisis. It is suffering from a failure of priorities.

The Bottom Line

This story is not about one person, one contract, or one department. It is about choices. Repeated choices. Lorain County has chosen to prioritize development schemes over workforce stability, narrative control over transparency, and insider ecosystems over public trust. Those choices did not happen in isolation. They reinforce each other. The strike was the spark. It forced into the open what had been building quietly for months and years. The video was the tell. It revealed how quickly leadership defaulted to moralizing restraint when the request came from workers. The relationships are the context. They explain how authority, influence, and resources circulate through overlapping boards, consultants, and appointed entities. The rejected audit is the proof of posture. When evidence challenged the story being told, the story was protected and the evidence was discarded. Fiscal responsibility is not measured by how forcefully officials say no to workers who lack leverage. It is measured by whether those same officials are willing to open the books, confront uncomfortable truths, and apply restraint where power and money actually sit. It is measured by whether audits are embraced or rejected, whether transparency is treated as obligation or nuisance, and whether standards are applied evenly or selectively.

Lorain County has not met that test. Instead, it has demonstrated a consistent willingness to mobilize resources for projects, partnerships, and priorities aligned with a narrow ecosystem of influence, while demanding sacrifice from the people who keep its most essential services running. It has shown that austerity is not a condition it endures, but a narrative it deploys. Until that changes, the question is no longer whether there is money. The record already answers that. The question is who the county believes deserves it, whose strain is considered acceptable, and whose voices are meant to be managed rather than heard. That is not a labor question. It is a governance one.

Final Thought: The Chain, the Choice, and the Consequence

If this story feels sprawling, that is because the system it describes is sprawling by design. None of what you have read exists in isolation. The strike. The video. The HR revolving door. The rejected audit. The Mega Site. The Port Authority. The radio towers. The mall. The boards. The consultants. The silence when records were requested. The confidence when workers were lectured. These are not separate controversies. They are links in the same chain. The chain begins with power concentrating away from public scrutiny and ends with workers being told to accept less.

Start at the spark. Job and Family Services workers reached a breaking point and said so publicly. Instead of meeting that moment with humility or transparency, the county chose confrontation. David J. Moore stepped in front of a camera and reframed the dispute as a morality play. Workers were unreasonable. Taxpayers needed protection. Leadership would be the adult in the room. That choice mattered because it was not reactive. It was strategic. It set the tone for everything that followed. Then look at who stood behind that narrative.

Human resources authority was not neutral in this dispute. It was embodied by Elise Aurvil, who had moved from private consultant to internal decision maker through a revolving door the public was never fully invited to examine. EHA Solutions functioned as de facto HR from the outside. Then that authority was absorbed inside the county. The same voice that advised on structure became the voice that validated austerity. When independent auditors challenged the structure, the challenge was dismissed. When workers challenged it, they were shamed. That is not coincidence. That is consolidation.

Now widen the lens. Aurvil does not exist in a vacuum. She is married to Steven M. Auvil, Vice Chair of Team NEO, the JobsOhio network partner that sits at the center of regional economic development strategy. No one needs to allege a phone call or a directive. That is not how influence works in modern governance. Influence is ambient. It is structural. It flows through shared tables, aligned priorities, overlapping boards, and a common understanding of what counts as important.

Editorial

And what has consistently counted as important in Lorain County is development. When Team NEO aligned projects appear, urgency follows. The Mega Site near the Lorain County Regional Airport did not stall because of cost concerns. Massive water and sewer investments were committed to make nearly a thousand acres shovel ready. This was sold as fiscal responsibility and future growth. At the same time, workers administering the county’s social safety net were told there was no flexibility and no money.

The same pattern repeats elsewhere. The Port Authority, created during Moore’s earlier tenure, becomes the vehicle for mall purchases and redevelopment schemes. Appointed boards steer land, financing, and contracts at arm’s length from voters. The emergency radio system saga unfolds through consultants, leases, towers, and system shifts that cost tens of millions and are justified as inevitable. When the Sheriff’s Office enters the picture, the posture is the same. Deference upward. Scrutiny downward. Silence where transparency should exist. Confidence where humility would serve the public better.

And when someone asks questions?

Records are resisted. Audits are rejected. Litigation is chosen even when the cost is predictable. The irony is almost too sharp to miss. A county that lectures workers about fiscal discipline repeatedly chooses paths that generate avoidable expense, legal exposure, and long term obligation. A county that claims to protect taxpayers spends freely to protect narrative control. This is where the corruption question actually lives. Not in a single illegal act. Not in a single name. But in a system that reliably produces the same outcomes. Development projects advance. Consultants are paid. Executive compensation is protected. Insider ecosystems remain intact. And when the people holding the system together ask for sustainability, they are told the cupboard is bare. That is not accidental. It is structural.

The irony is that the workers never needed to allege corruption to expose it. All they did was force a comparison. What the county says it cannot afford versus what it repeatedly chooses to fund. What evidence it embraces versus what evidence it rejects. Who gets believed versus who gets managed. Once that comparison is made honestly, the story breaks its own back. Because the record shows Lorain County does not lack money. It lacks balance. It lacks transparency. And it lacks the willingness to apply the same restraint to power that it demands from workers. Until that changes, the question facing this county is no longer about budgets or contracts or negotiations. It is about trust. Who this system is built to serve. And whether governance here exists to protect the public, or to preserve an ecosystem that no longer needs the public’s confidence to function. That is the final truth this chain of events reveals.

Related Reporting and Source Trail

This investigation builds on years of documented reporting examining Lorain County’s spending priorities, governance structure, infrastructure decisions, and resistance to accountability. Each of the stories below predates the Job and Family Services labor dispute and provides critical context for understanding why the county’s austerity narrative collapses under scrutiny.

These are not opinion pieces in isolation. Together, they form a record.

Emergency Radio System, MARCS, and Infrastructure Control

They Said It Was Just a Lease, But It Was the Lynchpin

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/they-said-it-was-just-a-lease-but-it-was-the-lynchpin/

This article documents how a single lease termination vote triggered the dismantling of the CCI based radio system and set Lorain County on a path toward the MARCS transition, committing the public to tens of millions in costs while officials minimized the decision as procedural.

The Contradictor in Chief: Dave Moore’s 8.15 Performance and the Unraveling of the CCI Sabotage Narrative

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-contradictor-in-chief-dave-moores-8-15-performance-and-the-unraveling-of-the-cci-sabotage-narrative/

This piece examines shifting justifications, internal contradictions, and public messaging failures as county leadership attempted to defend the radio system transition.

The CCI Lawsuit: How Secrecy and Mismanagement Brought Lorain County to the Brink

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-cci-lawsuit-how-secrecy-and-mismanagement-brought-lorain-county-to-the-brink/

A detailed look at how secrecy, governance failures, and avoidable litigation exposure emerged from the same decision making culture that later invoked austerity in labor negotiations.

Development Schemes, Spending Patterns, and Governance Failure

From Promises to Pattern: How Lorain County’s Big Ideas Keep Failing Its People

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/from-promises-to-pattern-how-lorain-countys-big-ideas-keep-failing-its-people/

This article tracks repeated high dollar development initiatives sold as investments that produced limited public benefit while generating legal fees, consulting costs, and infrastructure obligations.

Lorain County’s Five Year Spiral

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/lorain-countys-five-year-spiral/

A broader examination of declining trust, escalating costs, and compounding governance failures across multiple county departments and initiatives.

Clearwater’s Mirage: The Decade Old Sewer Scheme Reborn

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/opinion/clearwaters-mirage-the-decade-old-sewer-scheme-reborn/

This piece explores how long dormant infrastructure concepts were revived and advanced despite unresolved questions about cost, feasibility, and public benefit, echoing the Mega Site strategy discussed in this investigation.

Transparency, Litigation, and the Cost of Narrative Control

The Credit Card Scandal That Finally Exposed the Cracks in Lorain County’s Leadership

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-credit-card-scandal-that-finally-exposed-the-cracks-in-lorain-countys-leadership/

An examination of how weak controls and resistance to oversight exposed deeper problems in county management culture.

A Filing the Lorain County Commissioners Did Not Want the Public to Read

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/a-filing-the-lorain-county-commissioners-did-not-want-the-public-to-read/

This article documents how the county’s resistance to disclosure repeatedly forced information into the open through litigation rather than transparency.

The Barilla Judgment and What the Court Actually Found

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-barilla-judgment-and-what-the-court-actually-found/

A detailed breakdown of a court ordered judgment against Lorain County for public records violations, including statutory damages and attorney fees, illustrating the real financial cost of rejecting accountability.

Taken together, these stories form a continuous evidentiary record. They show how Lorain County repeatedly framed major decisions as inevitable, fiscally responsible, or minor in scope, while the actual outcomes involved structural change, significant public cost, and diminished oversight.

The Job and Family Services strike did not create these issues. It forced them into the open.

Legal and Editorial Disclosure

This publication is issued by Aaron C. Knapp in his capacity as an investigative journalist, commentator, and private citizen. The content reflects analysis, interpretation, and opinion based on publicly available records, direct communications, contemporaneous reporting, and first hand knowledge. Any factual assertions are intended to be grounded in verifiable sources believed to be accurate at the time of publication. This material is published in good faith on matters of public concern. Readers are encouraged to review original source documents where available and to draw their own independent conclusions.

Nothing contained herein is intended as legal advice, nor should it be construed as creating an attorney client relationship. This publication is provided for informational, journalistic, and commentary purposes only. Individuals facing specific legal, housing, or safety issues should consult a licensed attorney, qualified advocate, or appropriate professional of their choosing for advice tailored to their circumstances.

Where this publication discusses public agencies, nonprofit organizations, or advocacy programs, it does so for informational purposes only. Availability of services, eligibility criteria, and funding capacity may change without notice. No guarantee is made that any particular service, placement, or accommodation will be available or appropriate in a given situation.

Artificial Intelligence Disclosure

This article may have been drafted, edited, or refined with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools used to support organization, clarity, grammar, and formatting. All substantive content, factual framing, conclusions, and editorial judgment were directed, reviewed, and approved by the author. The use of AI does not replace independent reporting, professional judgment, or responsibility for accuracy. Any errors or omissions remain the sole responsibility of the author.

Limited Liability Company Disclosure

This content is published under the auspices of Knapp Unplugged Media LLC, an Ohio limited liability company. All views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any affiliated organizations, partners, or platforms. Knapp Unplugged Media LLC is not a law firm, social service agency, or crisis response provider. Nothing herein should be interpreted as offering professional services beyond journalism, commentary, and public interest reporting.

© Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All rights reserved.