A Jail in Freefall: How Lorain County Ignored Every Warning Until the Body Count Rose

From a paralyzed inmate, to an officer caught on video punching a man in a cell, to a jailhouse romance that spiraled into a murder-suicide, the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office keeps insisting each case is an isolated tragedy. The emails say otherwise.

INTRODUCTION: A PATTERN THEY WANT TO PRETEND DOESN’T EXIST

People ask why I keep digging. People ask why I file records requests, why I send emails, why I refuse to accept the “no comment” routine everyone else shrugs at. The answer is simple. Every time the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office tries to wave off a problem as a one-off incident, something worse happens. Every time a red flag goes unaddressed, somebody gets hurt. And every time someone inside that building screams for help, the people in charge look the other way until the damage is irreversible.

At some point, you stop treating these as separate tragedies. You stop pretending each case is its own universe. You stop letting officials talk in circles about “ongoing investigations” and “grieving for staff.” You stop accepting their excuses because the public deserves the truth. I didn’t create this pattern. I’m just documenting it because they refuse to.

The truth is that the Lorain County Jail has been bleeding warning signs for years, and every single one of them has been met with denial, delay, or a disappearing record. Three cases prove that beyond any doubt: the paralysis of Jeffrey Fry, the December assault caught on camera and ignored for months, and the slow, preventable collapse of a relationship between a corrections sergeant and a former inmate that ended with two people dead in a West 29th Street house. All of it happened in the same building. All of it happened under the same leadership structure. And all of it was preceded by specific warnings that were dismissed as if nothing could ever go wrong inside the Lorain County Jail.

This is what happens when a system refuses to fix itself.

THE TELLIER CASE: A NECK BROKEN IN FRONT OF A CAMERA AND A JAIL WITH NO NURSE TO TREAT IT

Start with May 2023, when Corrections Officer Brian Tellier slammed a handcuffed inmate, Jeffrey Fry, headfirst into a concrete wall hard enough to break his neck. I’ve watched the video. Everyone I know who has watched the video has the same reaction. Fry goes limp instantly — a man whose spinal cord has just been catastrophically damaged, falling forward with his hands cuffed behind him, unable to brace, unable to protect himself, unable to even understand what happened in the split second that changed everything. Tellier doesn’t pause. He doesn’t call for a medic. He doesn’t treat the moment like the medical emergency it obviously was. He drags Fry’s limp body down the hallway like he’s hauling a mattress, pulls him into a vestibule, and tosses him onto a gurney like he’s unloading a piece of equipment. That’s not restraint. That’s not “controlled movement.” That is exactly what it looks like: a man in uniform pretending nothing is wrong because admitting something is wrong would mean admitting he caused it.

But what happened after the assault is the part I can’t get past, because it exposes the larger truth the Sheriff’s Office has been trying to bury for years. When Fry hit that wall, the Lorain County Jail did not have a registered nurse on duty — not one — and no doctor, no physician assistant, no one with the authority or training to evaluate a spinal injury. The only medical professional in the building was a licensed practical nurse. And Ohio law is crystal clear: an LPN cannot assess or diagnose anything independently. They must work under the direction of an RN, a doctor, or a PA. None of those people were present. Not one. So the first people responding to a man whose spine had just been snapped were the same correctional staff who had no medical training beyond the standard jail courses and the LPN who legally could not perform the evaluation even if she recognized exactly what she was seeing.

This was not a small gap or a paperwork oversight. This was the jail running without the basic medical infrastructure the law requires. This was a facility responsible for detoxing people, stabilizing people in acute psychiatric crisis, managing chronic medical conditions, and responding to broken bones, overdoses, strokes, cardiac events, and yes, spinal injuries — with no RN to authorize anything and no physician to step in when the situation plainly demanded it.

Fry lay there paralyzed while staff tried to figure out what to do. They had no one on-site who could legally make the call. And that’s the moment that tells you the truth about the Lorain County Jail in that era. It wasn’t just that an officer acted with brutality. It was that the system surrounding that brutality was so hollow, so understaffed, and so nonfunctional that even if someone had wanted to do the right thing, the structure to support that response simply didn’t exist.

And this is where the excuses always start. “It was before Hall took office.” “It was an isolated incident.” “It was a staffing issue.” No. It was not isolated, and it did not end when Hall took over, because the cracks that allowed Fry to be paralyzed are the same cracks that let misconduct fester in silence, the same cracks that allowed Christopher Jackson to stand over a man in December 2024 and start throwing punches inside a jail cell, and the same cracks that allowed a corrections sergeant to engage in an inappropriate relationship with a woman in custody without a single person in leadership stepping in or demanding an internal review.

The Fry case is the blueprint. It shows you exactly how bad this system was allowed to get. It shows you what happens when a department operates in a culture where the story is always minimized, the video is always “under review,” the records are always “not available,” and problems are treated not as problems but as PR crises to be contained until the news cycle passes. The paralysis wasn’t the only tragedy in that room. The other tragedy was the total absence of a functioning, lawful, medically competent jail structure. That is the part no one wants to talk about, because once you admit the structural failure, you have to admit responsibility for everything that followed.

And it didn’t stop after Fry. It didn’t even slow down.

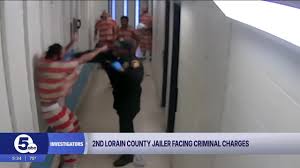

THE JACKSON CASE: A SYSTEM THAT PROTECTS ITS OWN EVEN WHEN THE VIDEO IS UNDENIABLE

By the time Christopher Jackson punched that inmate inside the Lorain County Jail on December 29, 2024, the department had every warning it needed. They had already gone through Fry’s paralysis case. They had already been publicly embarrassed. They had already promised reforms. You would think the lesson would have sunk in.

But what the Jackson case revealed was something worse than a single act of excessive force. It exposed a system that would rather reverse discipline than admit wrongdoing. A system that will bend over backwards to reinterpret video, reinterpret policy, reinterpret facts if that’s what it takes to shield an employee from consequences. And a system so tightly bound to its labor contracts that the end result looks less like accountability and more like ritualized protection.

The facts were simple. The inmate threw bodily fluids at Jackson. Disgusting, outrageous, and absolutely infuriating — no one disputes that. But jailers deal with hostile inmates every single day. Policy exists specifically because anger is expected. Professionalism is required. Discipline is mandatory. And Jackson didn’t follow any of it. He waited, re-entered the cell, and threw a punch. That moment, captured clearly on surveillance, was enough for the Sheriff’s Office to terminate him in April 2025. It took five months from the incident to termination, because even when the video is undeniable, discipline moves at the speed of cold molasses in Lorain County.

But here’s the part that still infuriates me: Jackson got his job back. Reinstated. Returned to duty. And not only reinstated — paid back pay. Paid taxpayer dollars for the time he wasn’t working because of his own misconduct.

Why?

Because the union contract made termination nearly impossible unless the department could prove that Jackson’s punch wasn’t a spontaneous reaction to being assaulted. They needed airtight evidence of intent, of planning, of a choice made with a calm mind. It didn’t matter that he left the cell. It didn’t matter that he came back. It didn’t matter that there was a pause, a moment to walk away, a moment when every part of his training told him to de-escalate. The arbitrator framed it as a “heat of passion” response to being attacked.

And just like that, the punch became defensible. The termination evaporated. Jackson came back.

Jackson’s case shows how the system treats jail violence: not as a crisis, not as a danger to community trust, but as a contractual puzzle where the end goal is never reform, just compliance with technicalities. The dropped criminal charges were even more insulting. Everything was caught on video, but prosecutors weakened themselves into a corner and walked away from charges they could have pursued. If the county had fought for accountability with even half the determination they fight to withhold public records, Jackson would not have returned.

Instead, they sided with “the process” over the truth. They used the contract as a shield, not a standard. And they made clear that the consequences of misconduct depend more on what an arbitrator thinks than what the public sees with their own eyes.

This is the environment that allowed the Coonrod situation to develop unchecked. This is what set the stage for a culture that acts shocked only after the body count rises.

LEGAL SIDEBAR: HOW THE SHERIFF’S OFFICE BLEW THE JACKSON CASE AND WHY THE UNION CONTRACT BROUGHT HIM RIGHT BACK

The Jackson case is the perfect example of what happens when a sheriff’s office tries to clean up a mess after it has already hardened into a legal problem. Everyone saw the video. Everyone agreed the punch was unnecessary. Everyone agreed the reaction was excessive. But none of that matters when the department fails to follow the specific disciplinary steps required by the collective bargaining agreement that governs jail staff. Once they missed those steps, Jackson’s job became legally protected no matter how bad the conduct looked.

The department made a series of procedural mistakes from the very beginning. They treated the incident like something they could discipline on instinct instead of following the precise series of notices, documentation steps, supervisory interviews, and rule citations required under the contract. The contract is rigid. It was negotiated to protect employees from political firings and emotional reactions by administrators. It demands that before any significant discipline can be imposed, the employee must receive written notice of the allegation, an opportunity to respond, a Loudermill-style hearing on the record, and proper classification of the alleged offense under the internal grid. The sheriff’s office skipped key parts of that sequence. It sounds technical, but in labor law these technicalities are everything. If you don’t follow the process, an arbitrator will reverse you every single time.

The second failure was the department’s decision to let the criminal case drift instead of driving it to a fast resolution. When Jackson was criminally charged, the sheriff’s office leaned on that as a justification for suspension instead of building their own airtight administrative case. Because the misdemeanor charges were weak and eventually collapsed, it created an opening that any union attorney could exploit. When the prosecutor fails to secure a conviction, the union simply argues that the department relied on an unproven allegation instead of its own investigatory record. That argument is devastating. It allows the arbitrator to say the discipline was based on a “non-sustained criminal allegation,” which is arbitrator-speak for “you didn’t do your job properly and now you’re trying to fire someone without the evidence required under your own rules.”

This is how Jackson wins even when Jackson is wrong. The department failed to preserve the strongest evidence in the correct procedural format. They failed to follow the contract timeline. They failed to articulate the discipline category that would hold up under arbitration. Once those mistakes were baked into the file, the union only had to sit back and wait. The minute the criminal case faltered, Jackson’s attorney could point to the incomplete internal record and say the punishment was not supported by the proper standard. The arbitrator doesn’t care about the video or the optics or public outrage. The arbitrator cares about whether the department followed the contract it signed.

The third and most predictable failure came from the sheriff’s legal strategy. Instead of building a clear case around “conduct unbecoming,” “excessive use of force,” and “violation of training standards,” they leaned on generalized statements and emotional framing. That is a guaranteed loss at arbitration. A sheriff can believe a punch was improper. A judge can believe it. A prosecutor can believe it. But unless the department ties that punch to a specific rule and documents every step of the investigation under the negotiated contract, an arbitrator will say the penalty was arbitrary. Once discipline is declared arbitrary, reinstatement becomes mandatory.

This is the part people don’t like because it feels unfair, but it is exactly how labor law works in Ohio. The union is not defending the conduct. They are defending the process. If the sheriff cannot follow his own process, the employee wins. It is not a moral victory. It is a procedural one. But it is binding.

That is why Christopher Jackson gets to return to a law-enforcement role even after the public was shown a video where he walks into a jail cell and hits a man who is already contained. It is not because the sheriff thinks the conduct was acceptable. It is not because the county believes the punch was justified. It is because the department mismanaged the investigation, mishandled the notices, relied on a weak criminal case, and violated their own bargaining agreement in the way they issued discipline.

A sheriff’s office that actually understands its own policies could have terminated Jackson with documentation that would withstand arbitration. Instead, they tried to discipline based on outrage rather than procedure. When you do that in a union environment, the employee comes back every time.

This is not an accident. It is a pattern. And this is why the most recent “decision” looks less like justice and more like institutional muscle memory. The department never fixes the underlying systems. They only react when video hits the public, and by then it is already too late.

The Coonrod Collapse: What They Knew, What They Hid, and What They Tried to Lecture Me About

Which brings us to the most recent crisis, the one the department keeps hiding behind the phrase “under investigation,” as if that phrase magically wipes away every missed warning, every ignored complaint, every email they refused to answer. I have watched the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office “investigate” things for years. I know exactly what it means when they say they are investigating. It means delays, excuses, disappearing records, missing videos, sudden claims of exemptions that do not apply, and a department that treats accountability like an optional luxury.

This case is no different. In fact, it is worse, because the truth was in their hands long before anyone died.

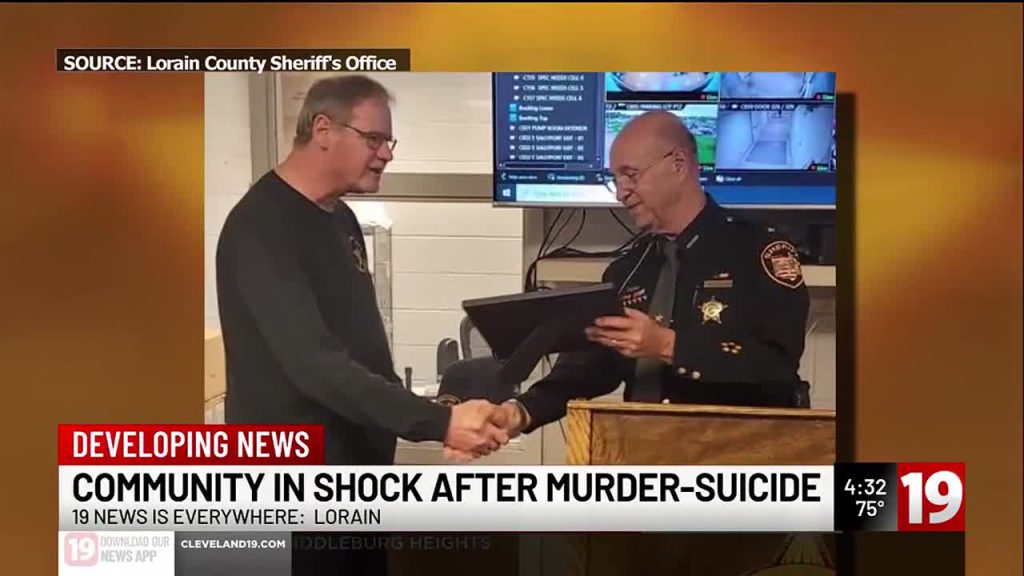

Two people end up dead inside a house on West 29th Street. Retired sergeant Anthony Coonrod and former inmate Emily Simmons. The official line from the Sheriff’s Office was predictable. He retired months earlier. He was not their problem. They made sure to emphasize that before they said anything else. They wanted the public to walk away believing that whatever happened between him and Simmons was private and had nothing to do with the conditions inside their jail.

Except that story collapses instantly when you look at the timeline I had already put in front of them.

For months, I had been requesting the tablet messages exchanged between Coonrod and Simmons while she was incarcerated. I asked in November. I asked again in January. Then March. Then April. Each time the department insisted that no responsive records existed. No explanation. No statutory citation. No acknowledgment that jail tablets are property of the county and fall under the jurisdiction of the public office, which means the messages are public records if they existed during his active employment. They simply dismissed the requests as if the logs did not matter.

Then came April 24. I received an email from Office Manager Alyson Jancsura. It contained a single line and an attachment. Her entire message read, “See attached retirement letter from the previous Sheriff.” That letter showed that his retirement was effective September 30, 2024. I responded immediately because the letter raised a new problem. In my email I asked, “So is it your contention that Coonrad wasn’t an employee when he was working in the jail sending the inmate messages? Was he there for a reason, if not for work?” That was the question they would not touch. Because if he was on the payroll and inside the jail sending messages to an inmate, then the policy violation happened under their watch. And they did not want that acknowledged.

They stayed silent.

Then June arrived. The welfare check. The bodies. The headlines. And I renewed my request, because now the stakes were obvious. The messages could reveal when the relationship started, whether boundaries were crossed while she was in county custody, whether anyone should have stepped in before she was living with the same man who had supervised her behind bars.

I did not receive transparency. I received a lecture.

Assistant Prosecutor Leah Prugh is the actual legal authority for the Sheriff’s Office. But instead of hearing from her, I was contacted by Anthony Nici, who holds a ceremonial role as the department’s so-called “civil affairs attorney.” He is not an Assistant Prosecutor. He has no statutory authority to issue binding legal positions on behalf of a sheriff’s office. He is a figurehead placed in a role the public is supposed to mistake for actual prosecutorial oversight.

That did not stop him from attempting to scold me.

He lectured me about how I was “out of line.” He told me that the Sheriff’s Office was “grieving” and that I should direct all communications only to the records inbox. He attempted to misuse legal citations in a way that only confirmed that he did not understand the statutory framework surrounding public records in a county jail. He claimed that tablet messages were exempt because they were “outside the scope of employment” even when I was asking specifically for messages created while Coonrod was still on duty, still supervising inmates, and still acting as a corrections officer. He tried to twist the Mobley case into something it was not, ignoring the part that made his argument collapse. Communications between a jail employee and an inmate are public records because they document a public office performing and failing to perform its duties.

This was the first time in all my years dealing with public offices that someone with no real authority tried to lecture me on the law after their own department failed to follow it.

But that was not the most egregious part.

Emily was not some anonymous former inmate out in the world when this happened. She was out on bond in a felony case. Someone had to sign for that bond. Someone had to list the residence she was living at. That residence belonged to Coonrod. If the residence belonged to a retired corrections sergeant who owned firearms, then pretrial services or the court or the Sheriff’s Office should have flagged it as an issue immediately. The fact that she was living with the very man who had supervised her inside the jail should have been an enormous red flag. They cannot claim ignorance. Jail staff told me about the relationship long before the bodies were found. The same staff who supported Hall during his election. The same staff who celebrated when he won because they believed he would clean up the mess. They had no problem leaking the information when they thought it would be a useful weapon. They suddenly developed moral objections when the truth implicated their own department.

The department also tried to hide behind the idea that the messages were exempt because they “did not document the office’s functions.” That is the oldest trick in the book. You cannot violate policy with an inmate and then claim the records documenting that violation were not part of your official functions. And even if family emails to me are not public records, messages exchanged between an active corrections officer and an inmate inside a county jail are. They are created on county-issued equipment. They exist only because the county runs a jail. They clearly document operations, oversight failures, and violations of policy.

So when Nici tried to hand me a neat little lecture about what counted as a record, I responded the only way someone in my position could respond. I told him that he did not give me direction. I told him they should have stopped this. I told him that the warnings were there long before this became a homicide investigation. I told him that CLEIRs does not apply to the issuing agency. And I told him that if they continued to stonewall me on a death investigation involving a former jailer and the inmate he bonded out and moved into his home, I would take them to the Court of Claims.

-Aaron Knapp

And still, the messages have not been produced.

Because they know exactly what those messages will show.

Because they know this relationship started inside their jail.

Because they know that someone could have intervened months before two people ended up dead.

Because ignoring warnings is what this department does best, from Assistant Prosecutor and Sheriff’s Counsel Anthony Nici, who tried to scold me while misapplying case law I know better than he does.

They told me to stop emailing the people who failed to act. They told me they were “grieving.” They told me I was “out of line” for stating what anyone paying attention already knew: this could have been prevented.

And the messages still have not been produced.

THE EMAILS THEY WISH I DIDN’T HAVE

This is the part they never expect me to show. They count on the public not knowing the timeline. They count on the records being buried long enough that no one connects the dots. They count on the confusion. I remove the confusion, because I kept everything.

The first cracks in their story start on October 9, 2024. I sent a formal records request directly to Jail Administrator Jim Gordon. He did not hedge. He did not stall. He did not claim exemptions or missing files. His response the next morning was simple and straightforward. He wrote that he had “obtained the requested information” and had already “forwarded it to Records Supervisor Jancsura.” There was no ambiguity. He acknowledged that responsive records existed and were being moved to the records division for production. That is their own administrator, in writing, confirming they had what I asked for. Months later, they expect the public to believe nothing existed. They want you to forget the email. I will not.

Then on April 24, 2025, Office Manager Alyson Jancsura emailed me and said, “See attached retirement letter from the previous Sheriff.” That was it. No explanation. No clarity. No answer to the actual question. The attached letter, signed by former Sheriff Phil Stammitti, simply confirmed that Sgt. Anthony Coonrod’s last official day was September 30, 2024. I responded immediately and asked the only question that mattered. If he was no longer an employee, then why was he in the jail communicating with an inmate? What purpose justified his physical presence and access? No reply ever came. Suddenly the retirement letter was supposed to be the end of the conversation, as if a date on a PDF resolved everything they refused to answer.

Then comes June 3, 2025, two days after both Coonrod and Emily Simmons were found dead. I asked again for the same records I had been requesting since the previous year. I asked for the video of Emily bonding him out. I asked for the tablet communications prior to his retirement, because that is the only period I ever asked for. That morning, I finally received a long email from the person they keep placing between the public and the truth, the man they want the public to mistake for the agency’s lawyer. His name is Anthony Nici, and although he signs his emails like a legal authority, he is not an Assistant Prosecutor. He is not the legal representative of the Sheriff’s Office. That job belongs to the Prosecutor’s Office and, specifically, to Assistant Prosecutor Leah Prugh. Nici operates more like a ceremonial shield, someone whose job is to send intimidating emails to citizens to shut down uncomfortable questions.

His June 3 response fit that role perfectly. He lectured me about “scope of employment.” He dropped case cites as if that would distract from the contradictions. He tried to reframe my request by insisting that tablet messages between a corrections officer and an inmate would somehow be exempt if the officer was acting outside his job duties. He quoted Mobley in a way that ignored the central point of the ruling, which is that communications between incarcerated individuals and correctional staff are presumptively public unless a specific exemption is identified. He did not identify one. He simply asserted it, hoping the email alone would be enough to shut the door.

Then he claimed something that directly contradicted his entire message. He told me that the video I had requested was “sent on 11/13/2024” and that it was “no longer available due to CLEIRs.” That statement did not surprise me, because CLEIRs is their favorite refuge whenever accountability enters the room, but the problem was simpler than that. The video was never sent. Not in November. Not in December. Not ever. When I told him that, the conversation ended. They stopped replying altogether.

On that same morning, I also told them what they did not want to hear. I told them they should have stopped this. I told them they allowed a former inmate who was out on bond in a pending felony case to live with a retired corrections officer who possessed firearms. If she listed his address as her residence, then the responsible agencies should have confirmed whether that home was safe, whether weapons were present, and whether there were conflicts created by the fact that he had been her jailer. They knew those things because staff inside the jail told me about the relationship months earlier. These were the same staff who supported Jack Hall during the election. They were eager to expose corruption when it implicated the old administration. Their enthusiasm changed the moment accountability landed in their own building.

And then there were the calls from Coonrod’s family members. They began contacting me, unsolicited, after the deaths. I informed the Sheriff’s Office because those calls mattered. They mattered because they showed urgency, they showed awareness, and they showed concern that the department did not seem to share until two people were already gone. But Nici chose to ignore that too. He told me I was “out of line.” He tried to redirect the conversation to their grief, as if the public is required to remain silent when government failures hurt people.

Everything in this pattern is designed to create distance between the agency and the facts. They acknowledge records exist only until those records become damaging. They say videos were sent that were never delivered. They insist data is exempt even though they refused to document the functions in the first place, which makes it impossible for them to now claim it is “non-record.” They hide behind CLEIRs even though CLEIRs applies to investigative agencies holding investigative files, not to the issuing agency that produced the video. They repeat the phrase “no responsive records exist” until repetition becomes hope.

Except I kept the emails. I kept the timeline. I kept every contradiction they thought the public would never see.

This is not confusion. This is not grief. This is not misunderstanding. This is a deliberate effort to shrink the paper trail until the truth can no longer fit inside it.

And I will not let them do that.

THE STONEWALLING: CLEIRS, MOBLEY, AND THE ART OF MAKING RECORDS VANISH

This is the part they hope the public never sees, because it shows exactly how the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office treats the law when the law becomes inconvenient. Every time I pressed for answers about Sgt. Anthony Coonrod’s communications with inmate Emily Simmons, and every time I asked for the documents they knew could reveal the timeline of their own inaction, they reached for the same three excuses that have carried them through years of crisis. They said the CLEIRs exemption prevented disclosure. They said no responsive records existed. They said the case was under investigation so they could not say anything further. They repeated those phrases like a script, as if repetition would eventually replace the truth.

The CLEIRs exemption does not protect them here. The statute governs confidential law enforcement investigatory records. It does not give a sheriff’s office the authority to pretend that operational records created long before any investigation existed suddenly vanish into thin air. The exemption is not retroactive. It does not permit an agency to erase records that were never investigative in the first place. Communications between a corrections officer and an inmate, created on a government controlled tablet system while both individuals were under the supervision of the sheriff, fall squarely within the statutory definition of a public record. They are created, stored, transmitted, and maintained on the system of a public office. That is the only requirement under the law for a document to be subject to disclosure. Even if a portion of a record contains exempt information, agencies are required to redact and release. They cannot bury an entire category of records simply because they do not like what might be inside.

Their reliance on Mobley is equally dishonest. Assistant Prosecutor Leah Prugh is the actual legal authority for the Sheriff’s Office, but it was their ceremonial lawyer, Anthony Nici, who attempted to lecture me on case law he has no authority to interpret. He misquoted Mobley by lifting a portion of the opinion about whether inmate kites are public records and twisted it into an argument that messages between a jail employee and an inmate somehow stop being public records if the employee is communicating “outside the scope of his employment.” That argument is nonsense. That is not what Mobley says. That is not what the Public Records Act says. And the Ohio Supreme Court has made clear for decades that the test is not whether a document was created within the scope of employment, but whether the record is created or received by a public office and documents the activities of that office. Nothing in the statute allows an agency to erase accountability simply by declaring that misconduct falls outside scope. If anything, an improper relationship between a correctional officer and an inmate is precisely the kind of activity the public has a right to know about.

They know this, and it is why they cannot bring themselves to put it in writing. Instead, they pretend these messages never existed, despite the fact that jail staff told me directly about the relationship, told me when it began, and told me Coonrod was communicating with her long before the retirement date they cling to as a shield. I emailed Hall. I emailed Cillo. I emailed the Chronicle. I gave them an opportunity to fix the problem before it exploded in their faces. They refused to even acknowledge it.

Their denials crumble under their own contradictory emails. Jail Administrator Jim Gordon confirmed on October 9, 2024, that he had obtained responsive records and forwarded them to Records Supervisor Jancsura. That admission alone destroys the Sheriff’s Office’s later statements that no responsive records exist. If nothing existed, Gordon could not have forwarded anything. If nothing existed, they would not have pointed me to a retirement letter months later. If nothing existed, they would not have had to invent new legal excuses each time I asked again.

And the timeline matters. Emily Simmons was not some anonymous former inmate. She was out on bond in a felony case. She lived at the residence of the officer who had supervised her inside the jail. That residence contained firearms. That residence should have been checked for safety. The Sheriff’s Office knew she was living with a retired sergeant who had been her jailer. The relationship was not a mystery. Staff told me directly. Staff who supported Hall’s election. Staff who were outraged at what they had witnessed. Staff who believed this information mattered when it could be weaponized against the previous administration, but suddenly changed their tone once their preferred candidate was in power.

The Sheriff’s Office uses CLEIRs, Mobley, and the supposed “ongoing investigation” to delay, deflect, and deny. None of those excuses apply to the public records I requested. None of them justify ignoring the warnings that could have prevented two deaths. Their refusal to produce records is not a legal decision. It is a reputational one. They know transparency would expose the fact that they were warned. They know producing the records would show they allowed a vulnerable, unstable woman to be released into the home of a man who had been her jailer, a man with access to weapons, a man whose relationship with her began when she had no ability to freely consent.

They cannot allow that truth to emerge. So they bury the records. They cite laws that do not apply. They insist everything is under investigation while refusing to investigate the one thing that matters most. They dragged their feet until two people wound up dead, and then they hid behind one final defense. They pretended that because Coonrod was retired, he was no longer their responsibility. That is their position. That is their excuse. And that excuse collapses the moment you line it up against their own emails.

This is why the records matter. This is why the stonewalling must be exposed. And this is why I keep fighting them. They know exactly what they buried. They know exactly what they ignored. And they know exactly what those records would reveal about the warning signs they chose not to see.

THE OVERSIGHT VOID: AN INSPECTOR GENERAL WHOSE EXISTENCE MEANS NOTHING IF NO ONE LISTENS

The Sheriff’s Office likes to talk about oversight as if creating a job title means the culture has changed. After the Jackson case became impossible to ignore, they announced an Inspector General position and rolled it out like a turning point. It was described as a safeguard, an accountability mechanism, a promise that patterns of misconduct would finally be caught before they turned into lawsuits, news stories, or tragedies. The problem is that oversight is not a press release. Oversight is not a slogan. Oversight is not the existence of a desk, a badge, or an organizational chart.

Oversight is what happens when people with authority decide to act on warnings placed in front of them. And that is exactly what never happened here.

Long before the Inspector General position existed, the red flags surrounding Anthony Coonrod were already known inside the jail. Staff talked about it privately. They whispered about tablet messages that never should have been exchanged. They knew a relationship was forming between a corrections sergeant and a woman in custody. They knew he was communicating with her at times when he was on duty and paid by the taxpayers. They were willing to tell me because they thought this information would hurt the old administration. They changed their tune after Election Day, once the new leadership realized the same facts implicated their own silence.

None of this was unknown to the Sheriff’s Office. The warnings were there during Stammitti’s administration. They were there the moment Hall took office. They were there in the emails I sent directly to Hall and to Prosecutor Tony Cillo. They were there in the requests I filed in November, January, March, and April, each one asking for the same thing: the tablet communications that could show when the relationship started, how far it went, and whether it had been ignored by staff.

Each request was answered with the same line. They told me no records existed. They did not cite an exemption. They did not explain their search. They did not follow the law that requires them to identify the specific reason for any denial. They simply repeated a phrase as if repetition could erase the responsibility they carried.

And when the Inspector General role was created, nothing changed. No one followed up on the warnings that predated his position. No one revisited the earlier requests that flagged the relationship. No one treated the claims seriously until two bodies were found on West 29th Street. Oversight did not fail because the Inspector General lacked authority or tools. Oversight failed because the people above and around him chose not to act, not to ask questions, and not to open a single drawer that might prove they should have seen this coming.

The truth is that the Inspector General cannot inspect anything the Sheriff’s Office refuses to acknowledge. He cannot review tablets the department insists contain no data. He cannot investigate misconduct the leadership won’t classify as misconduct. He cannot look into the warnings I provided if the people with power decide that those warnings are worth ignoring.

Oversight does not die because of one person. Oversight dies when a culture decides that accountability is optional. Oversight dies when leadership refuses to confront the truth because the truth carries political consequences. Oversight dies when officials care more about preserving the institution’s image than preventing the next tragedy.

That is the oversight void we are dealing with. A system where the existence of an Inspector General is nothing more than a talking point, because the people who could empower him choose to pretend that nothing is wrong. A system where silence is easier than responsibility. A system where warnings are buried, where records vanish, and where leadership only starts caring once the damage is irreversible.

And that is why Emily Simmons is dead. Not because the department lacked an Inspector General, but because the warnings that could have saved her were ignored long before he ever existed.

LEGAL ANALYSIS SIDEBAR: WHAT THE LAW ACTUALLY SAYS ABOUT ALL OF THIS

Ohio law is not vague, flexible, interpretive, or subject to whatever creative spin the Sheriff’s Office wants to put on it when something blows up in their hands. The statutes that govern staff–inmate contact, public records, and law enforcement transparency are explicit. They were designed to prevent exactly the type of scenario that led to two bodies being found on West 29th Street. When the department pretends the law is unclear, they are not confused. They are covering themselves.

Ohio Revised Code 2907.03 criminalizes sexual conduct by a corrections officer with an inmate, and the law makes no allowances for “retirement proximity,” “off-duty status,” or anything else. If the relationship begins inside the jail, if the grooming begins during custody, if the contact begins while one person is incarcerated, the law is triggered. There is no safe exit ramp where a jailer can simply retire and retroactively sanitize everything that happened before his last day on payroll. Consent is legally impossible in that setting, and Ohio courts have affirmed this over and over again. That is why the statute exists.

Ohio Revised Code 2921.44 covers dereliction of duty by public employees. Any employee who knowingly or recklessly violates a departmental duty or fails to perform a required obligation is subject to criminal liability. If a jail employee uses internal systems to contact an inmate for personal reasons, that is a violation of duty. If a supervisor knows about it and looks away, that is a violation of duty. If the department refuses to investigate after being put on notice, that is a violation of duty. The law does not excuse misconduct because the employee is popular, close to retirement, or has friends in the building.

The Ohio Public Records Act is equally direct. Ohio Revised Code 149.43 requires the release of any record that documents the functioning of a public office. Courts have repeatedly held that electronic communications created on or transmitted through a government system are public records. A department does not get to declare something “non-public” because it is embarrassing or politically inconvenient. The Ohio Supreme Court’s holdings in cases like State ex rel. Glasgow and Natl. Broadcasting Co. v. Cleveland instruct agencies to produce the records and redact what is truly exempt. They do not permit agencies to erase the entire record.

The Sheriff’s Office keeps trying to twist the Mobley decision into a magical shield where inmate communications suddenly vanish if the employee acted “outside the scope of employment.” That is not what Mobley says. Mobley held that inmate “kites” and communications documenting the functioning of the institution are public records. It did not hold that improper or unauthorized conduct is exempt. In fact, Ohio courts have historically rejected attempts by public officials to escape disclosure by labeling misconduct as “unofficial.” If the communication occurs on government time, in a government facility, on a government device, or through a government-controlled system, it is a public record unless a specific statutory exemption applies. “We do not like what this shows” is not an exemption.

CLEIRs is the other shield they keep waving. CLEIRs is an exemption used by law enforcement to protect investigatory work product. It does not apply to the issuing agency’s own administrative records. It does not apply to videos that were already acknowledged as existing. It does not apply to tablet messages created months before any criminal investigation began. It certainly does not apply to a jailer bonding out an inmate he had a relationship with. When they reach for CLEIRs, it is because they have nothing else to stand on.

Public records law is designed to prevent exactly this type of opacity. The courts have been clear: an agency may redact actual statutorily protected information, but it must still produce the remainder of the record. A department cannot declare a video “non-existent” after telling the requester it was produced. A department cannot declare messages “outside the scope of employment” when the entire problem is that the conduct occurred inside the jail while the employee was still on payroll. A department cannot pretend an inmate–staff relationship becomes lawful because the staff member submitted a retirement letter. The law does not bend to protect an office from embarrassment.

The truth is simple. Ohio law required them to preserve and produce these communications. Ohio law required them to investigate when warnings were raised. Ohio law required them to confront the staff–inmate relationship the moment it started. The only reason any of this appears complicated is because the Sheriff’s Office has chosen to make it complicated. They have created a maze of excuses, denials, and contradictions because transparency would expose the failures that led directly to the deaths of Emily Simmons and Anthony Coonrod.

There is no legal ambiguity here. There is only a department that refuses to follow the law because doing so would mean admitting they were warned, they ignored the warning, and a preventable tragedy occurred because of that decision.

CONCLUSION: A SYSTEM THAT WAITS FOR A BODY TO HIT THE FLOOR BEFORE ADMITTING THERE’S A PROBLEM

And because if they had listened the first time, or the second time, or the third time, long before Emily Simmons was found dead beside a retired corrections sergeant, the warning signs were everywhere. They weren’t subtle. They weren’t buried. They weren’t hidden from leadership. I emailed Sheriff Jack Hall directly. I emailed Prosecutor Tony Cillo. I even emailed the Chronicle because I was tired of watching the same people pretend they had no idea what was happening inside the jail they were running.

The most miserable part is that they knew. They absolutely knew. I didn’t get this information from rumor mills or anonymous tips on Facebook. I got it from employees inside the jail, employees who supported Jack Hall during the election, employees who were eager to talk when they thought the fallout would land on someone else. Once Hall actually took office and the accountability became real, the same people stopped wanting to talk. Suddenly the story changed. Suddenly nobody saw anything. Suddenly the problem was the guy asking questions.

-Aaron C. Knapp

But the timeline doesn’t lie no matter how many people try to rewrite it. Tellier broke a man’s neck in 2023 while the jail did not have a single qualified nurse or doctor on site. Jackson was caught on video punching an inmate in 2024 and the department acted like it was some shocking new discovery. And while all of that was happening, a corrections sergeant was building a relationship with a woman inside the jail, a woman he would later live with, a woman he would die next to. The department’s official stance is to act surprised and confused, as if this all just appeared out of thin air. It didn’t. I told them about it. Staff told me about it. I sent the emails. I asked the questions. They ignored all of it until someone died.

This isn’t three separate incidents. It isn’t three different eras. It isn’t three different sheriffs, administrations, cultures, or conditions. It is the same system, repeating the same failures, pretending each disaster is a brand-new surprise. A jail without adequate medical staff. A discipline process that only activates once something leaks to the public. A records division that magically loses videos and messages only when those records would make the department look negligent. A leadership structure that sits on its hands until tragedy becomes undeniable.

You asked why I keep pushing. This is why. Because every time this system collapses, someone else pays the price. And because if they had listened when they were warned — the first time, the second time, the third time — Emily Simmons might still be alive. I didn’t write any of this in hindsight. I wrote it in real time, in emails they received, in messages they chose to ignore. They want the public to believe the collapse happened suddenly. But it didn’t. It was slow, predictable, preventable, and it happened step by step while people in charge pretended nothing was wrong.

This is what it looks like when a department only admits a problem after a body hits the floor.ons might still be alive.

FINAL THOUGHT: THE PART THEY WILL NEVER ADMIT OUT LOUD

I have told this story before, but never this plainly.

When Jack Hall was running for Sheriff, I was useful to him. My investigations. My documentation. My willingness to call out the failures under the Stammitti administration. My persistence with public records. My voice. My credibility. Jail employees who were backing Hall fed me information about misconduct. They told me what was happening inside that building because they thought a new administration would finally clean it up.

I was a weapon when they needed one.

-Aaron C Knapp

And then the election was over.

The moment I became inconvenient, the moment my questions shifted from helping their campaign narrative to exposing their new failures, they threw me out of the frame. They stopped replying. They pretended records did not exist. They acted like they had never asked for my help. They watched while Tia Hilton filed complaint after complaint against me. They watched while false claims piled up. They watched while court staff played games with my name and my reputation. They watched and did nothing.

Worse than nothing. They let it happen.

To this day, the Prosecutor’s Office and the Sheriff’s Office have still not complied with a sitting judge’s order to investigate the McCann matter. They have not referred it to a special prosecutor. They have not answered a single substantive question. They have not acknowledged the evidence. They have not even attempted to correct the record.

They know what the law requires. They simply refuse to follow it because they do not want to be accountable for the mess they created.

That is the story behind this story. Not just a department with gaps or blind spots or inconvenient tragedies. A department that used me when it was politically beneficial and abandoned me the moment I expected the same truth from them that they once demanded from others. A department that wants the public to believe they are transparent but conducts themselves like a closed circle that punishes anyone who dares to insist on honesty.

People ask why I keep pushing.

This is why.

Because the minute you stop asking questions in Lorain County, somebody in power decides you no longer matter. Because silence is the only thing that keeps their version of events alive. Because the moment I stop demanding accountability, the people who lied, stalled, hid records, and enabled retaliation will point back at their silence and call it proof I was wrong.

I will not give them that luxury.

Not then. Not now. Not ever.

LEGAL NOTICE & AUTHOR DISCLOSURE

This article represents the author’s independent investigation, analysis, and opinion based on publicly available records, law, personal correspondence, and firsthand involvement in the matters described. All statements regarding public officials or public institutions concern matters of public concern. Any errors of fact will be corrected upon request with appropriate documentation.

Nothing in this publication is intended as legal advice. Readers should consult qualified counsel for legal guidance relating to their own circumstances. Any legal discussion herein is provided solely for informational and journalistic purposes.

AI-ASSISTED WORKFLOW DISCLOSURE

Portions of this article were drafted, edited, or refined using AI-assisted writing tools. All final content, factual assertions, interpretations, and conclusions were reviewed, approved, and adopted by the author. Responsibility for the accuracy of the reporting and the opinions expressed rests solely with the author.