A Filing the Lorain County Commissioners Did Not Want the Public to Read

On January 2, 2026, Cleveland Communications Inc. filed a twenty eight page opposition brief in federal court in its case against the Lorain County Board of Commissioners. The filing appeared quietly on the PACER docket. There was no press release. No public explanation. No acknowledgment from the Lorain County Commissioners that their legal defense had just been directly confronted in detail.

https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:VA6C2:da50d35d-3325-490c-ae24-721e410d51d4

That silence is telling.

In the filing, CCI challenges the County’s effort to collapse the entire case into what it has repeatedly described as nothing more than a failed contract. As the brief states plainly, the County’s position depends on ignoring the broader scope of alleged harm, asserting that CCI’s only injury is the termination of its county wide contract,

a characterization the filing describes as false and incomplete.

According to CCI, the record instead shows injury well beyond a rescinded vote. The filing alleges that CCI was harmed through the denial of business opportunities, damage to its good will and business reputation, and retaliatory conduct,

including actions that occurred after the lawsuit was already pending. Those allegations matter because, as the brief emphasizes, federal law protects against injury to business or property, not merely the loss of a single agreement.

The opposition also directly confronts the Commissioners’ reliance on legislative immunity. CCI argues that immunity cannot be used to

collapse years of conduct into a single legislative actin order to shield alleged threats, interference, and retaliation that occurred outside the legislative process itself. The brief warns that accepting the County’s framing would allow officials to insulate non legislative conduct simply by pointing to a later vote.

These are not rhetorical flourishes. They are targeted statements designed to force the court to answer a narrow but consequential question. Are the Lorain County Commissioners entitled to shut this case down before discovery by redefining the facts, or do the allegations now on the record require sworn testimony and document production?

That is why this filing matters.

And that is why the Commissioners’ silence about it matters even more.

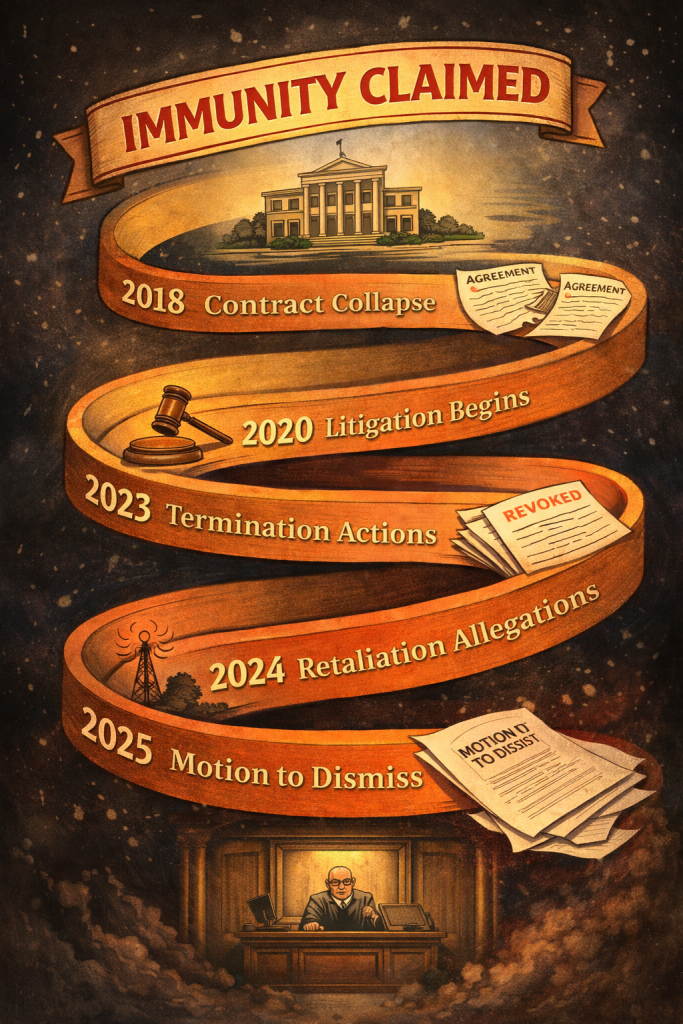

The County’s Preferred Narrative: One Vote, No Harm

For more than two years, the Lorain County Board of Commissioners has relied on a deliberate and remarkably consistent narrative to defend this case. Reduce everything to a single legislative act. Assert absolute immunity for that act. Insist that no legally cognizable injury exists outside a contract the County now claims was never valid in the first place.

In motion after motion, the Commissioners have framed the dispute as a routine procurement failure stripped of all surrounding context. The contract, they say, lacked a fiscal certificate required under Ohio law. The Board later voted to rescind it. According to this telling, nothing else matters. No harm occurred. No rights were implicated. The analysis begins and ends with a vote.

If that framing holds, nearly every claim in the case collapses on cue. The RICO counts fail because there is no proximate cause beyond a rescinded agreement. The due process claims fail because no protected property interest could ever have vested. The First Amendment retaliation claims fail because, under the County’s theory, no adverse action exists beyond the legislative act itself. Legislative immunity becomes the all purpose shield, ending the case before depositions, documents, or sworn testimony ever enter the picture.

That is precisely why the January 2 filing exists.

CCI’s opposition is not an attempt to relitigate the existence of a contract. It is a direct challenge to the County’s effort to compress years of alleged conduct into a single procedural endpoint. The filing argues that the Commissioners’ narrative survives only by ignoring alleged injuries that occurred before the vote, alongside it, and after the lawsuit was filed. Once those allegations are placed back into view, the simplicity of the County’s story disappears.

The January 2 filing exists to show that the

one vote, no harmnarrative does not merely oversimplify the case. It distorts it.

What the January 2 Filing Actually Says

CCI’s January 2 opposition does not deny that a contract vote occurred. It does not attempt to wish that vote away. Instead, the filing argues that Lorain County’s fixation on the rescission vote is a deliberate misdirection designed to collapse a much broader record into a single procedural endpoint.

As the brief explains, the County’s argument rests on the assertion that CCI’s only injury is the termination of its county wide contract,

a premise the filing calls both inaccurate and incomplete. According to CCI, that framing survives only by ignoring injuries that do not depend on the contract at all.

The opposition states that CCI was injured through

the denial of business opportunities, damage to its goodwill and business reputation, and retaliatory conduct,harms that the filing emphasizes are cognizable under federal law regardless of whether a single contract was later rescinded. The brief further notes that these injuries were not hypothetical or speculative, but ongoing and cumulative, affecting CCI’s ability to operate, compete, and maintain existing systems.

The filing is especially direct on the issue of timing. It alleges that significant harm occurred outside the legislative act the County now claims is dispositive, including conduct that preceded the rescission,

actions that occurred alongside it,

and retaliation that continued after this lawsuit was filed

.

That distinction matters because, as the brief underscores, federal law does not require all injury to flow from a single decision. It requires injury to business or property, period.

On legislative immunity, the opposition is blunt. It warns that the County’s theory would allow officials to collapse years of conduct into a single legislative act

and then declare everything surrounding that conduct immune from review. The brief argues that immunity does not function that way, and that accepting the County’s position would improperly shield alleged threats, interference, and retaliation that occurred outside the legislative process itself.

In one of the filing’s most consequential passages, CCI argues that the County’s approach

depends on redefining the factual record,not on addressing it. The opposition makes clear that legislative immunity may protect votes, but it does not erase reputational harm, market exclusion, or post filing retaliation, nor does it extinguish claims arising from conduct that is administrative, coercive, or retaliatory in nature.

If the allegations in the January 2 filing are taken as true, as they must be at this stage, the County’s effort to funnel every claim through a single rescission vote does not merely oversimplify the case. It fails to engage with what the complaint actually alleges.

That is why this filing matters more than prior motions. It does not just respond to the County’s arguments. It exposes how narrow those arguments must be to work at all.

At its core, the January 2 filing accuses Lorain County of attempting to win not by disproving the allegations, but by shrinking the story until nothing remains but a single vote.

Legislative immunity,CCI argues, cannot be used to erase reputational harm, market exclusion, or retaliation that occurred before, during, and after that vote. The filing’s message is unmistakable. If the County’s theory is accepted, accountability ends the moment officials label their conduct legislative.

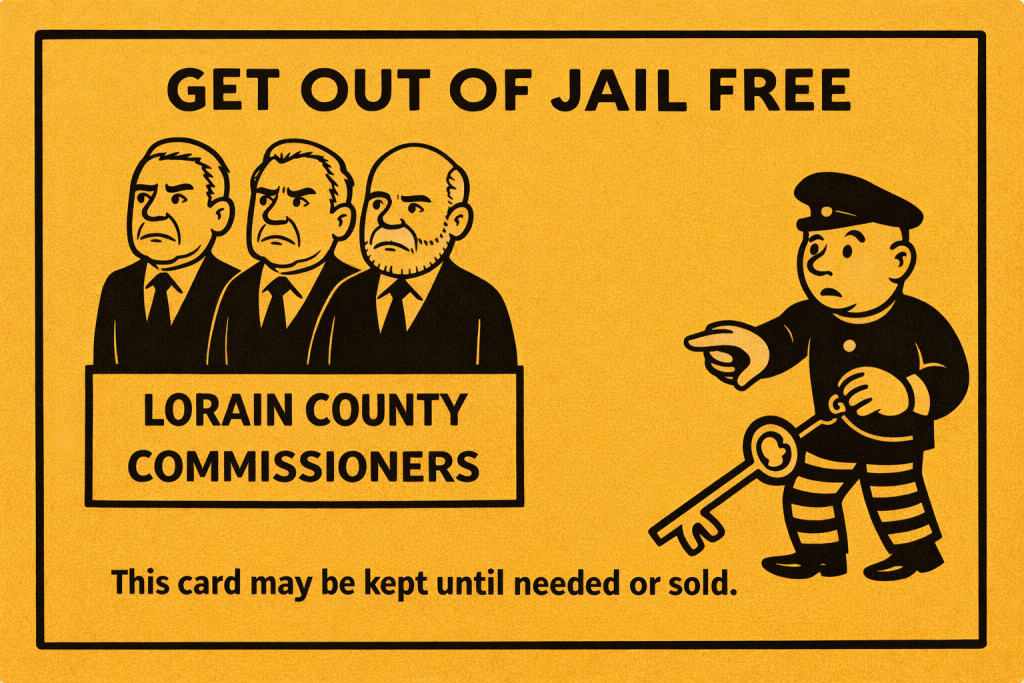

Legislative Immunity Is Not a Get Out of Jail Card

One of the most aggressive positions advanced by the Lorain County Board of Commissioners is that legislative immunity bars nearly every claim in the case. The County’s theory is sweeping. Because the Board ultimately voted, everything connected to that vote is said to be protected, regardless of motive, context, timing, or collateral conduct.

CCI’s January 2 filing responds by reframing the issue the court must actually decide. The question, the brief explains, is not whether a vote occurred. It is whether the County can use that vote to shield conduct that was not legislative at all.

As the filing makes clear, legislative immunity protects legislative acts.

It does not protect threats, retaliation, misuse of investigations, interference with third parties, or conduct that occurs outside the legislative process itself. Nor, the brief argues, does immunity automatically attach when a vote targets a single entity rather than advancing a general policy or budgetary objective.

The opposition relies on controlling precedent to emphasize that courts are required to examine substance, not labels. A vote can be administrative in substance. A resolution can be retaliatory in effect. And immunity does not attach simply because officials later take a formal action related to earlier conduct. As the filing warns, accepting the County’s position would allow officials to retroactively launder non legislative conduct through a subsequent vote.

That distinction is not academic. It determines whether public officials can insulate years of alleged conduct by pointing to a single meeting agenda item and declaring the entire surrounding record off limits. The January 2 filing argues that legislative immunity was never meant to function that way, and that using it as a blanket shield would turn a narrow protection into an instrument for avoiding accountability.

In plain terms, CCI’s message to the court is this. Legislative immunity protects lawmaking. It does not erase the rest of the story.

Retaliation After the Lawsuit Changes Everything

Perhaps the most consequential portion of the January 2 filing involves conduct that occurred after the lawsuit was already pending. This is where the County’s preferred defenses stop functioning altogether.

According to CCI, Lorain County officials took additional adverse actions only after CCI exercised its constitutional right to seek judicial relief. Among the most significant allegations is interference with tower access necessary for CCI to operate its independent emergency communications system. The filing alleges that this interference was not incidental, accidental, or unrelated, but was instead tied directly to CCI’s decision to bring the case to federal court.

The opposition states that these actions constitute retaliation for protected activity, emphasizing that they occurred after this lawsuit was filed

and therefore cannot be justified by alleged defects in a pre litigation contract. In plain terms, the filing argues that whatever the County believes about the original procurement dispute, it does not explain or excuse what happened next.

This matters because post filing retaliation cannot be folded into legislative immunity tied to an earlier vote. It cannot be justified by arguing that no contract ever existed. And it cannot be dismissed as collateral when the alleged conduct interferes with an existing, functioning system unrelated to the rescinded agreement.

As the filing makes clear, the County’s strongest defenses all depend on collapsing the case into a single legislative act that occurred before the lawsuit. Retaliatory conduct that follows the filing of a complaint stands on its own,

outside that framework, and is evaluated under a different constitutional standard entirely.

Courts have long recognized that government entities may not retaliate against contractors or citizens for petitioning the courts. That protection does not disappear because the party seeking relief once did business with the government. If the allegations in the January 2 filing are true, the County’s reliance on legislative immunity and contract technicalities does not reach this conduct at all.

This is why the retaliation allegations change the posture of the case. They do not merely add another claim. They sever the County’s attempt to use a single vote as a universal defense. Once the lawsuit was filed, the rules changed. According to CCI, the County did not.

This Is Not Just a CCI Story

What makes the January 2 filing especially relevant to Lorain County residents is that it does not exist in isolation. For anyone who has followed the County’s recent history, particularly the controversies surrounding Cleveland Communications Inc., the Midway Mall, the Lorain Port Authority, and repeated instances of questionable legal and financial decision making, the posture taken in this case is immediately recognizable.

Across those stories, a consistent pattern has emerged. When substantive questions arise about how decisions were made, who benefited, and whether public resources were responsibly managed, the response is rarely a full accounting. Instead, disputes are reframed as technical misunderstandings. Legal exposure is minimized through narrow procedural arguments. Oversight is delayed or avoided altogether by invoking jurisdictional barriers, immunity doctrines, or contract formalities that conveniently prevent discovery.

The January 2 filing argues that this case has followed the same script. When the factual record expanded beyond a simple procurement issue, the County narrowed the frame. When allegations extended past a single vote, they were dismissed as irrelevant. When post lawsuit conduct entered the record, it was treated as collateral. And when accountability threatened to move beyond pleadings and into sworn testimony, legislative immunity was raised as a stopping point.

This pattern is not about Cleveland Communications Inc. as a company, nor is it about one rescinded contract. It is about how institutional power is exercised and defended in Lorain County. It is about whether public officials respond to scrutiny by answering questions, or by structuring defenses designed to ensure those questions are never formally asked.

Your prior reporting has shown how this approach plays out across different contexts. Whether the issue is emergency communications, redevelopment projects, port authority spending, or legal advice that later proves costly, the mechanics remain strikingly similar. Substance gives way to procedure. Context is stripped away. And the public is left with explanations that resolve nothing beyond the immediate legal threat.

That is why the January 2 filing matters beyond the courtroom. It challenges not just the County’s legal defenses in one case, but a broader method of governance that relies on procedural compression rather than factual resolution. If the court allows this case to proceed, it will test not only CCI’s claims, but the durability of a defensive strategy that has shaped far more than this single dispute.

And that is why this is not just a CCI story. It is a Lorain County story.

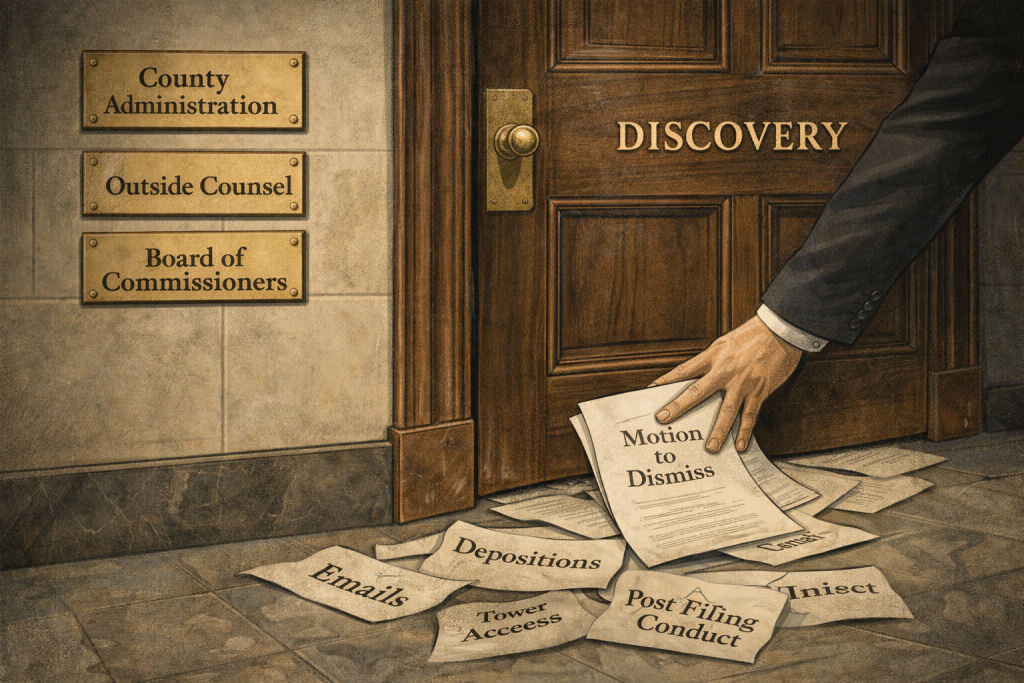

Why This Filing Matters Now

Procedurally, the timing of this filing is not incidental. It is critical. The court has already declined to dismiss this case outright and instead allowed the complaint to be supplemented. That decision carries weight. It means the judge did not find the claims facially deficient and believed additional allegations could materially affect the legal analysis. In other words, the court signaled that the story alleged in this case was not complete.

The renewed motion to dismiss now pending before the court is the Lorain County Commissioners’ most consequential attempt to prevent the case from advancing into discovery. If that motion is granted, the dispute ends on paper. If it is denied in whole or in part, the case enters a phase where facts, not framing, control what happens next.

Discovery matters here because discovery is where narratives are tested against reality. Depositions require sworn testimony. Document production reveals what was said internally, when it was said, and who knew what at the time decisions were made. Communications that are currently summarized in pleadings become records that can be compared, verified, and contradicted if necessary. Motive stops being an abstraction and becomes something that can be examined.

That importance is heightened by the passage of time and by the human realities involved in this case. One of the central figures repeatedly referenced in the litigation, Jeff Armbruster, has publicly acknowledged serious health issues. That fact does not change the merits of the claims, but it does underscore why timely discovery matters. Memories fade. Availability changes. Testimony that can be obtained today may not be obtainable later in the same form, or at all.

Courts recognize this reality. Discovery is not merely about burdening defendants. It is about preserving evidence while it can still be preserved, and allowing claims to be evaluated based on a full factual record rather than assumptions or procedural shortcuts. When cases are terminated before discovery, the public never learns whether allegations were true or false. They only learn that the questions were never asked under oath.

If even one claim in this case survives dismissal, the posture changes immediately. Depositions follow. Requests for emails, texts, and internal memoranda follow. Decisions that have so far been defended through legal arguments become factual questions subject to scrutiny. The case moves from what lawyers say to what officials did.

That is why the January 2 filing matters now. It is not simply another brief in a long docket. It is the document arguing that this case has reached the point where discovery is not just appropriate, but necessary.

And that is why it is newsworthy.

The Question the Court Will Have to Answer

At this stage of the case, the court is not being asked to decide who is telling the truth or to weigh competing versions of events. It is being asked to answer a narrower but consequential question. Do the allegations, taken as true as federal law requires at this phase, plausibly state claims that warrant discovery and factual development.

The Lorain County Board of Commissioners insists that no legally cognizable injury exists outside what it characterizes as a void contract. Under that theory, the case ends before any witness is sworn and before any internal communication is produced.

CCI argues the opposite. It contends that the record already before the court shows injury well beyond a rescinded agreement, including reputational harm, exclusion from ongoing and future opportunities, interference with existing systems, and retaliation that continued after the lawsuit was filed. According to the January 2 opposition, those injuries are independently actionable and cannot be erased by narrowing the case to a single vote.

The filing forces the court to confront that conflict directly. It also forces a broader reckoning with how Lorain County has defended its actions not only in this case, but across a growing number of disputes where procedural arguments have been used to avoid substantive examination of the facts.

Whether this case ultimately proceeds or not, the issues raised by the January 2 filing illuminate how accountability is contested in Lorain County. They show how decisions affecting public resources and private actors are defended when challenged, and how often the fight turns not on what happened, but on whether anyone will ever be allowed to ask under oath.

That is something the public deserves to understand.

This Case Does Not Stand Alone in Lorain County

For readers who have followed Lorain County litigation over the last several years, the themes raised in the CCI filing are not unfamiliar. The posture taken by the County in this case mirrors arguments and strategies that have appeared repeatedly across unrelated disputes involving public records, employment retaliation, contract rescissions, and constitutional claims.

Again and again, the County’s response to uncomfortable allegations has not been to resolve the underlying facts, but to narrow the legal frame until discovery becomes impossible. Claims are recast as mere technical defects. Injuries are minimized or denied outright. Immunity doctrines are invoked early and often, not as defenses to liability after facts are known, but as gatekeeping tools to prevent facts from being known at all.

In other Lorain County cases, the public has seen similar reliance on procedural shields. Public records disputes have been framed as clerical misunderstandings rather than statutory violations, even where delays stretched for months or years. Retaliation claims have been reduced to personnel matters, even when adverse actions closely followed protected speech. Contract disputes have been stripped of context, ignoring the conduct that preceded and followed the paper trail.

What makes the CCI case especially significant is that the January 2 filing explicitly calls this strategy out. It does not merely argue that the County is wrong on the law. It argues that the County’s version of events is artificially compressed to avoid scrutiny of conduct occurring before, during, and after the official actions it now claims are immune.

That pattern matters because courts do not operate in a vacuum. When similar defenses recur across multiple cases, they begin to look less like coincidence and more like institutional habit. Whether the habit is lawful is precisely what discovery is designed to test.

This is why the County’s insistence that this case is nothing more than a failed contract rings hollow to those who have watched other Lorain County controversies unfold. The facts may differ, the plaintiffs may change, but the defensive architecture remains strikingly consistent.

If the court allows this case to proceed, it will not just be deciding the fate of one vendor’s claims. It will be deciding whether Lorain County can continue to rely on procedural compression to shield substantive conduct from examination. That question has implications far beyond Cleveland Communications Inc.

And that is why this filing, though buried in PACER and written in dense legal language, deserves public attention.

Editorial and Legal Disclaimer

This article is based on publicly available court filings, docket entries, and related public records. All descriptions of legal claims, defenses, and procedural posture are drawn directly from documents filed in court or from the official record unless otherwise stated.

This reporting does not assert findings of fact by any court. Allegations described herein are allegations unless and until proven in a court of law. The purpose of this article is to inform the public about matters of governmental action, litigation involving public bodies, and the legal arguments being advanced in a case of public concern.

Nothing in this article constitutes legal advice. This publication is not intended to influence any judicial proceeding, juror, or court, nor does it purport to predict the outcome of any litigation. Readers should not construe analysis or commentary as a substitute for consultation with a licensed attorney regarding any specific legal matter.

All opinions expressed are those of the author and are based on a good faith review of the public record. Any errors are unintentional and will be corrected promptly if identified.

Transparency and Fairness Notice

This article focuses on a specific court filing because of its relevance to public accountability and governance in Lorain County. Coverage of this filing does not imply endorsement of any party’s claims, nor does it preclude future reporting that may include additional filings, rulings, or responses from other parties.

Where possible, this publication seeks to contextualize litigation within broader patterns of government conduct without speculating about motives or outcomes. Parties discussed in this article are welcome to provide responses, clarifications, or corrections for inclusion in future updates.

About the Author

Aaron Knapp is an investigative journalist, licensed social worker, and public records advocate based in Lorain County, Ohio. He is the founder and publisher of Aaron Knapp Unplugged, an independent journalism platform focused on local government accountability, public records enforcement, and court based reporting grounded in primary source documentation.

Knapp’s work centers on analyzing public records, litigation filings, and government decision making that affect communities at the local and county level. His reporting frequently examines how public institutions respond to scrutiny, how legal defenses are deployed to avoid factual review, and how procedural mechanisms shape public accountability.

In addition to his journalism, Knapp is a licensed social worker in the State of Ohio with a professional background in juvenile justice and court adjacent systems. His dual experience in social services and investigative reporting informs his focus on institutional power, transparency, and the real world consequences of government action.

Knapp has been involved in numerous public records disputes and Court of Claims actions and has written extensively about access to public information, constitutional rights, and the intersection of law, policy, and governance. His reporting emphasizes document driven analysis, long form context, and adherence to the public record over speculation or partisan framing.

Aaron Knapp Unplugged exists to follow stories beyond press releases and surface explanations, into the records, filings, and factual details where accountability is ultimately decided.

3 thoughts on “A Filing the Lorain County Commissioners Did Not Want the Public to Read”