Episode 11: The Interviews OPS Left Behind — How Lorain Buried the Truth to Protect Its Power

Aaron C. Knapp Lorain Politics Unplugged Lorain Politics Unplugged

Apr 23, 2025

I. The Pattern of Silence

The OPS report into Lt. Corey Middlebrooks’s allegations against Chief James McCann was 383 pages long—meticulously formatted, legally structured, and devoid of accountability. Titled an “investigative report,” it presented itself as impartial. But the final product omitted or minimized 24 interviews—testimonies from officers of all ranks who either directly corroborated Middlebrooks’s claims or contradicted the department’s defenses. Some were labeled “irrelevant.” Others were never referenced again.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Lt. Corey Middlebrooks described the experience plainly: “They want me gone. They’re trying to force me out.” He made the statement not as speculation, but after his demotion, reassignment, and a humiliating “performance test” that even Deputy Chief Failing later admitted was not standard protocol. “It wasn’t meant to evaluate,” Middlebrooks said. “It was meant to fail me.”

OPS dismissed his narrative as circumstantial and emotionally charged. But it wasn’t just Middlebrooks saying it.

Retired Sergeant Dennis Davis—who spent years inside the department—testified, “These motherf—ers were protecting their own. I spoke truth to power. They punished me.” Davis’s own career stalled after raising concerns about overtime fraud and the KKK placard in Captain Reiber’s office. He was reassigned, ignored, and eventually pushed out. He said he witnessed racial slurs in writing on bathroom mirrors and inside locker rooms: “N***** go home.”

Officer Miguel Baez echoed the sentiment. “It didn’t feel like a performance review,” Baez said about Middlebrooks’s forced testing on support service tasks. “It felt like a setup.” Baez also confirmed that he was ordered by McCann to read a reprimand aloud to Middlebrooks—an act Baez later called “public humiliation.” OPS chose not to feature that detail.

Detective Ed Soto described a pattern of subtle punishment. “They kept me in the dark and fed me shit,” he said of his isolation after being tied to a use-of-force case he didn’t initiate. “It was like watching the same thing happen to Corey, just ten years later.”

Detective Payne’s Garrity interview was included in the OPS investigative material. In that transcript, he recalled a hallway conversation in which McCann allegedly said: “I need a dirty cop. I wish you were a dirty cop. I need someone taken care of. I need Corey Earl dirty.” But although that quote exists in the record, OPS omitted it entirely from the summary, findings, and conclusions. There was no inquiry, no internal ethics flag, no mention of what that quote implied about McCann’s state of mind or intent.

What all of these voices share is not just corroboration of discrimination or retaliation—it’s the experience of being silenced, sidelined, or discredited when speaking up. Some officers like Lt. Camarillo gave neutral accounts, denying knowledge of racism but confirming odd reassignments and conflicting accounts. Others, like Capt. Reiber, admitted to keeping a KKK sign in his office. OPS included none of it in its summary findings.

And then there were those who stayed quiet. Sgt. Greszler said, “Corey said stuff about being treated unfairly… but people didn’t want to get involved.” Sgt. Tomlin put it bluntly: “He felt singled out. We all knew that. We just didn’t say it out loud.”

OPS investigators heard those interviews. They recorded them. They transcribed them. And then they omitted them. This wasn’t an accident. It was institutional editing. Because if you include what the rank and file are actually saying—about racism, about retaliation, about manipulation of policy—then you have to acknowledge a system that protects the top by burying everyone else.

The pattern wasn’t just in how Corey was treated. It was in how the truth was managed.

II. The Placard Nobody Wanted to See

Witnesses: Reiber, Baez, Davis, Arce, Mathewson, Reinhardt

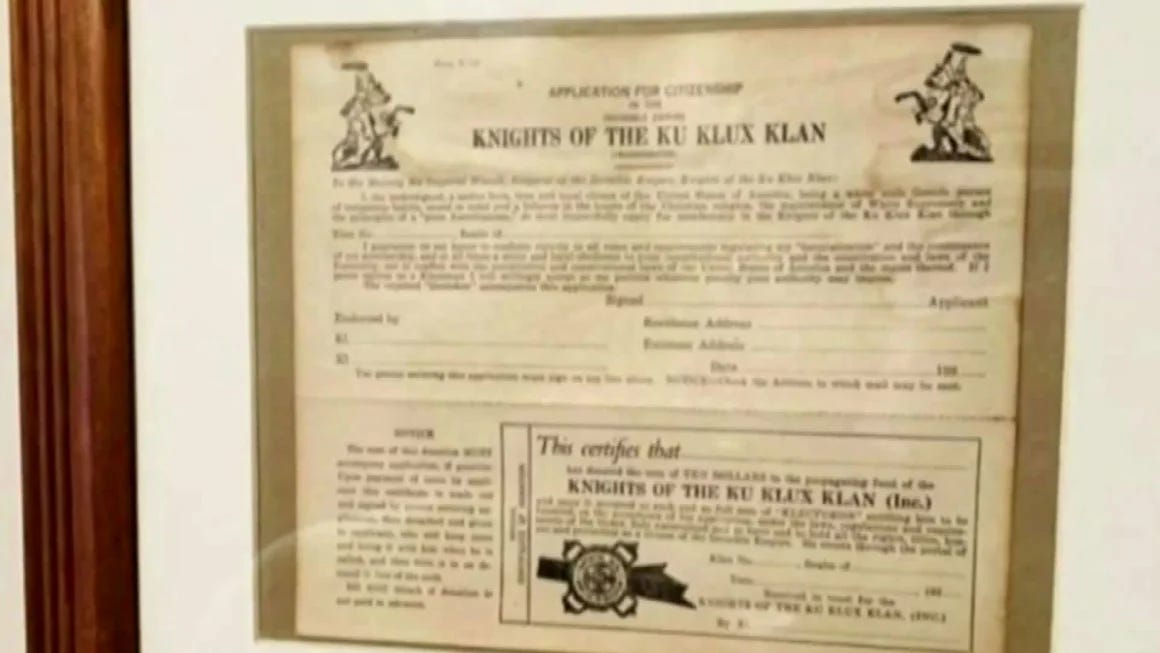

It wasn’t a rumor. It wasn’t a misunderstanding. According to multiple officers, a sign referencing the Ku Klux Klan was physically displayed inside a Lorain Police Department office—and several officers recall seeing it with their own eyes.

Retired Sergeant Dennis Davis was the most direct. “It said ‘KKK Park Here.’ It looked like a legit parking sign,” he said. “It was red and white, like city signage. I saw it in Reiber’s office with my own damn eyes.” Davis also recalled that he and Lt. Corey Middlebrooks were the only two to raise concerns about it at the time. “Nobody said a goddamn word until me and Middlebrooks showed up,” Davis testified. “They acted like it was a funny souvenir. I didn’t laugh.”

Officer Miguel Baez also confirmed the placard existed. “It said KKK plain as day. I saw it,” he said in his interview. He described it being hung on the wall as a kind of SWAT memento—one that should never have been in any police office, let alone the captain’s.

Captain Mathewson added further detail. “Yeah, there was a photo from a SWAT event. Todd Reed and his K9 in front of a building that had a KKK sign on it,” he said. “Reiber had it displayed. I don’t think he meant anything racist by it, but I know Middlebrooks didn’t take it that way. I remember he got it taken down after Corey complained.”

Officer Arce remembered being in the office when the placard was present. “I saw something… maybe KKK or something about protesters. I remember Corey asking about it, and the mood changed real fast,” Arce said. “It got quiet. I didn’t say anything. I should’ve.”

Even Lt. Reinhardt, who initially expressed uncertainty, acknowledged he had heard about the placard multiple times from Middlebrooks. “Corey would tell that story a lot. I challenged him on it once and he didn’t back down. He said it was real and he saw it,” Reinhardt said. “I think he believed it had meaning.”

And then there was Captain Reiber himself. When confronted about the placard, Reiber admitted it existed. “It was from a Butler County rally,” he said. “Some officers brought back signs as a joke. Mine said ‘KKK Park Here.’ I had it on the wall for a while. Corey saw it and didn’t like it, so I took it down.”

What Reiber described as a “souvenir” or “joke” was, for others, a painful symbol of racial trauma and institutional indifference. What some dismissed as decor, others experienced as a warning.

And yet the final OPS report makes no mention of it—not in the summary, not in the conclusions, not in the departmental culture analysis. The placard that multiple officers confirmed, the placard that Reiber himself admitted to displaying, was erased from the official narrative. (The KKK placard is acknowledged, but OPS downplayed its significance and failed to act on multiple corroborations)

It wasn’t just the sign that got removed. It was the story behind it.

III. Retaliation by Reassignment

Witnesses: Swanger, Failing, Greszler, Mathewson, Vrooman, Middlebrooks

The reassignment of Lt. Corey Middlebrooks to Support Services in late 2022 marked a turning point. Unlike any prior internal personnel action in recent memory, Middlebrooks was removed from his captain duties and placed in a desk role traditionally assigned to entry-level administrative staff—before any formal demotion or disciplinary action was finalized.

Former Lt. Swanger, who had previously held the same role, confirmed this was a break from protocol:

“He was still a captain when they moved him. That didn’t make sense. No one had ever been reassigned like that before a decision was made.”

Swanger also noted that Middlebrooks confided in him, believing the reassignment was retaliatory:

“He said he thought the Chief was out to get him. That they were trying to embarrass him.”

Deputy Chief Failing provided crucial insight. He admitted that McCann orchestrated a “performance test” for Middlebrooks to evaluate his support service competency. The test, according to Failing, included tasks such as unlocking vehicle releases, radio inventory, and software access—procedures for which Middlebrooks had received no training.

“It wasn’t standard protocol. It felt more like documentation in case they needed to discipline him,” Failing stated.

He also noted that when Middlebrooks failed several tasks, McCann was furious.

“He yelled. He wanted it on record. That was different from how we handled these things before.”

Sgt. Greszler also observed the tension.

“Middlebrooks felt like they were setting him up. He said it a lot,” Greszler told OPS investigators. “He didn’t trust that they were helping him succeed in the role.”

When asked whether he saw any coaching or mentoring being provided, Greszler said,

“Not really. It was more like they were checking boxes.”

Captain Mathewson offered firsthand experience with the same position and agreed the job was overwhelming without support.

“When I took that role, Failing trained me. He walked me through everything over weeks. Corey didn’t get that. He was given a broken computer and told to figure it out.”

Mathewson confirmed that Middlebrooks had difficulty accessing even the most basic systems.

“The first week, his printer didn’t work. He had to borrow dispatch login credentials. No one set him up for success.”

Sgt. Vrooman described the experience as isolating:

“He wasn’t trained. He was just put in there with a bad setup. When I saw him, he looked completely frustrated.”

Vrooman also emphasized that this was not just poor onboarding—it was a deliberate tactic.

“They knew what they were doing. He wasn’t given the same ramp-up others got. It felt strategic.”

Middlebrooks himself said in his Garrity interview:

“They pulled me from the position, gave me no guidance, told me to handle everything myself, and then started documenting everything I couldn’t figure out.”

He described it as sabotage wrapped in process:

“They knew if they didn’t officially demote me right away, they could make it look like a transition. But I knew what it was.”

OPS investigators acknowledged these statements but minimized their implications. The reassignment was never formally evaluated as a possible act of retaliation. Instead, it was described as a “lateral change pending investigation.”

The officers who spoke out saw something different. A job with no training. A captain stripped of his authority. A leader being reshaped into a liability.

Middlebrooks summarized it best:

“They gave me the hardest job in the building and made sure I had no tools to do it.”

IV. A Quote Too Dangerous to Acknowledge

Witness: Detective Payne

Among the most disturbing revelations in the 383-page internal report is the one the OPS team didn’t fully confront. It came from Detective Craig Payne, whose Garrity interview was indeed part of the official record. Yet the line that should have triggered ethical alarms, internal scrutiny, and possibly external intervention was completely unmentioned in the final conclusions:

“I need a dirty cop. I wish you were a dirty cop. I need someone taken care of. I need Corey Earl dirty.”

Those are the words Detective Payne attributed directly to Chief James McCann during a hallway conversation. Payne said the Chief approached him casually but with unmistakable intent. Payne declined the implication, but the message was clear: McCann wanted someone who would act outside the law to neutralize Middlebrooks.

OPS investigators heard this quote. They recorded it. It’s right there in the transcript. But when it came time to summarize the findings, weigh credibility, and determine whether there was a culture of retaliation or intimidation, this statement was nowhere to be found.

It wasn’t that they didn’t believe it—it’s that acknowledging it would have required action.

Instead, OPS focused on procedural discrepancies. They framed the investigation as a workplace misunderstanding with racial “undertones” but no proof of targeted harm. They included charts, email logs, and administrative footnotes. But the Chief of Police stating he needed “a dirty cop” to go after a subordinate? That was just too radioactive to touch.

Payne’s quote doesn’t stand alone. It sits atop a mountain of similar accounts—Baez being used as a tool of humiliation, Middlebrooks being set up to fail, and senior officers admitting they saw a pattern but didn’t speak up. This quote was the blueprint behind the broader retaliation campaign, and OPS chose to pretend it didn’t exist.

The silence wasn’t passive. It was protective.

And the report wasn’t just incomplete. It was complicit.

V. The Whispers of Discrimination

Witnesses: Santiago, Soto, Davis, Baez, Arce, Middlebrooks

What OPS dubbed “interpersonal tension” was, to those living it, racial hostility. The report routinely downplayed allegations of discriminatory behavior, treating them as vague or unsubstantiated, even when multiple officers gave matching accounts of slurs, symbols, and cultural targeting.

Officer Abner Santiago delivered one of the most damning recollections. He testified that during a 1999 incident at the Island Club on Broadway, Chief McCann stormed in and shouted:

“I’m tired of all these n*****s and sp*cs.” stated James McCann, then sergeant, now Police Chief City of Lorain

Santiago had worked private security at the bar. He said McCann, then an officer, struck walls with a baton and forcibly cleared patrons. Santiago said the memory haunted him. He had kept it to himself for years—until compelled to testify.

Detective Ed Soto, a Puerto Rican officer, recalled being mocked as a “terrorist” in front of federal agents. “He said it right to me,” Soto told investigators. “He meant it as a joke, but you don’t say that shit when you’re standing next to Marshals.”

Sergeant Dennis Davis backed up Middlebrooks’s claims about racist graffiti. “I saw it myself,” Davis said. “The mirror said ‘n***** go home.’ That wasn’t the first time.” He also confirmed hostile interactions in the locker room—remarks from fellow officers that were racial in nature.

Officer Baez remembered similar language, particularly from Lieutenant Stack. “He talked about parties with mostly Black kids,” Baez said. “He’d say stuff like ‘bet they got watermelon and roaches.’ Everyone just laughed. Corey didn’t.”

Officer Arce, in one of the more reserved interviews, admitted he witnessed what he called “borderline” racial joking. “It wasn’t all the time,” he said, “but it happened. Corey would shut it down. He wasn’t afraid to speak up, and I think that made him a target.”

And then there was Middlebrooks himself. In his interview, he recalled numerous instances—both overt and subtle. “They’d say stuff like ‘smile so I can see you in the dark,’” he said. “Sometimes I wasn’t sure if it was a joke or a warning.”

OPS acknowledged some of these quotes in the appendix but concluded that “no sustained pattern of racial discrimination” could be confirmed. But how many officers need to speak the same truth before it’s called a pattern?

The whispers weren’t whispers at all. They were statements made under oath. The only silence was the one maintained by OPS, which chose not to draw lines between the stories.

What these men described wasn’t just workplace tension. It was a hostile environment where race was weaponized through language, policy, and selective enforcement.

And OPS let it pass with a footnote.

VI. The Loyalty Trap

Witnesses: Baez, Middlebrooks, McCann (Garrity), Payne

Retaliation wasn’t just overt. It was ritualized. OPS investigators overlooked or downplayed the subtler tactics—targeted exposure, weaponized transparency, and forced loyalty tests—that defined how dissent was suppressed within the Lorain Police Department.

One such tactic involved Officer Miguel Baez. According to Baez, Chief McCann ordered him to read the written reprimand issued to Lt. Corey Middlebrooks. Not to a crowd. Not in front of Corey. But to himself, under orders—and then to internalize it, digest it, and explain it to Middlebrooks in a personal conversation that left them both rattled.

Baez recalled being stunned. “He showed me your reprimand,” Baez later told Corey. “I didn’t know what to say. He just said, ‘Read this.’” The act itself—being made to read internal discipline about a respected colleague—felt, to Baez, like psychological maneuvering. “He made me the messenger. It wasn’t about information. It was about dominance.”

Middlebrooks remembered the moment when Baez told him what happened. “He looked sick about it,” Corey said. “He said he didn’t understand why he was dragged into it. That’s when I knew this wasn’t about discipline. This was about sending messages.”

OPS treated the incident as irrelevant. There was no inquiry into McCann’s motive, no examination of how disclosure of internal reprimands to uninvolved parties—under the guise of public records—might constitute retaliation or ethical breach.

In McCann’s own Garrity interview, he admitted he ordered Baez to read it: “It was worth pissing Corey off to save Baez’s career,” McCann said. “I wanted Baez to understand who he was dealing with. That’s my f—ing name on the policy.”

That wasn’t leadership. That was leverage.

In a separate instance, Detective Payne said McCann approached him about retaliation. “I need a dirty cop,” Payne recalled McCann saying. “I wish you were a dirty cop. I need someone taken care of.” The someone was Middlebrooks.

OPS did not cross-reference this quote with the Baez incident. They did not ask whether McCann had a pattern of dragging other officers into personal vendettas. They simply filed the quote away and concluded there was no pattern.

But there was a pattern. McCann didn’t just retaliate himself. He used others to do it. He conscripted his subordinates into retaliation theater. Some resisted. Some complied. All were damaged.

OPS documented the moving parts. What it refused to do was name the machine.

VII. A Culture of Fear

Witnesses: Tomlin, Thompson, Vrooman, Morris, Camarillo

Not every officer used the word “discrimination.” Many avoided it.

But in interview after interview, what emerged was a consistent portrait of isolation, fear, and quiet complicity. The officers who didn’t speak in support of Middlebrooks said just enough to describe the climate he operated in—and why others stayed silent.

Sgt. Tomlin was blunt: “Corey felt singled out. That’s how I took it.

He didn’t say ‘retaliation,’ but he said, ‘They’re watching me.’” He recalled Middlebrooks expressing frustration about orders being overridden and assignments changing without notice.

Lt. Thompson said the same thing: “He talked about how he was being monitored, like they were waiting for him to screw up. He was frustrated with the process.”

Thompson had served on the FOP committee that handled the controversial MOU that altered captain qualifications. “Corey opposed it,” he said. “He felt it was fast-tracked for people who hadn’t earned it.”

Sgt. Vrooman described a strong professional rapport with Middlebrooks. “He was a great cop. I never had a problem with him. But you could tell something was happening. He wasn’t set up for success in that support role.” Vrooman recalled watching Middlebrooks struggle with equipment and system access and being surprised at how little support was provided. “No one was helping him,” he said. “It felt intentional.”

Captain Morris gave one of the more contradictory interviews. He said he never heard Corey mention race, but also acknowledged that Middlebrooks was “guarded” and seemed like he “didn’t feel safe being open.” When asked whether he saw signs of unfair treatment, Morris deflected: “He seemed unhappy. But some people always are.”

Lt. Camarillo offered a more procedural view. He said he wasn’t aware of retaliation, but confirmed that “some transfers and testing procedures were unusual.” He acknowledged that the MOU vote had caused tension and that “Corey was vocal about what he thought was unfair.”

OPS relied heavily on these neutral or partial accounts in its findings. But neutrality in this context was a kind of institutional defense. When the stakes are high, silence serves power.

None of these men outright denied that Middlebrooks was targeted. Most simply said they didn’t know—or that they didn’t see it directly. But taken together, their testimony confirms that everyone knew something was off.

OPS failed to recognize that fear isn’t always loud. Sometimes it looks like neutrality. Sometimes it sounds like careful phrasing. Sometimes it shows up as a blank space on a form where “discrimination” should have been written in.

The absence of outrage in the report wasn’t proof that nothing happened. It was proof that officers were trying to survive.

VIII. The Final Witness

Witness: Sanford Washington, Safety Service Director (Ret.)

The last interview on the record—omitted from OPS’s final conclusions—came from one of the highest-ranking civilians involved: then–Safety Service Director Sanford Washington. While not a patrol officer or union member, Washington held a critical vantage point inside Lorain’s government structure. His words should have mattered.

Middlebrooks alleged that McCann threatened Washington behind closed doors, saying that after he was done with Middlebrooks, “Sanford is next.” When OPS questioned Washington about this, his response wasn’t denial. It was discomfort. “He never told me that,” Washington said. “But McCann keeps a lot to himself.”

McCann, for his part, claimed that Washington was engaged in unethical, back-channel conversations with Middlebrooks. But when asked directly, Washington responded:

“That never happened. We never had any private one-on-one meetings. Only group staff discussions.”

OPS never resolved the contradiction. They simply left it hanging—a conflict of testimony too sensitive to analyze. But Washington went further, confirming the dysfunction in leadership.

“McCann lacks impulse control,” he told investigators. “He says things he has a right to say, but they’re not the right thing to say.”

Washington also confirmed that he was present during a formal discrimination complaint involving another officer, Joseph Gibson. He noted that Middlebrooks sat in on the meeting as a witness. OPS tried to use this to frame Middlebrooks as someone who had “no concerns” about discrimination. But Washington clarified:

“Corey didn’t say anything affirming or denying it. He was just there.”

Even in neutrality, Washington’s testimony cut against the OPS narrative. He described McCann as “a jerk to everybody,” but added, “That doesn’t mean it’s not racism. It just means he doesn’t hide it well.”

When OPS drafted their findings, Washington’s interview was shelved. The report made no mention of McCann’s alleged threat, nor of the culture Washington described. Once again, the testimony of a key witness was cast into the void.

It’s not that the OPS team didn’t listen. It’s that they didn’t want to hear.

Final Thought

The OPS report did not fail to uncover the truth. It chose not to acknowledge it.

The testimony was there: twenty-four interviews, each a thread in a tapestry of institutional retaliation, racial hostility, and ethical collapse. Some officers gave blunt warnings. Others whispered through cautious phrasing. A few stayed silent, and their silence was telling. But taken together, these accounts revealed a department that punishes dissent, protects power, and buries those who speak out.

And perhaps most infuriating—most disheartening—is how many stood by while overt racism occurred. While slurs were scrawled on mirrors, while jokes about lynchings and roaches echoed through locker rooms, while a literal KKK placard sat in an office—people looked away. Senior officers, line supervisors, clerks, commanders—they saw it, and they said nothing. Their silence was not just complicity. It was cowardice.

OPS had the evidence. They had the Garrity interviews, the quotes, the dates, the complaints, the corroborations. And still, they reached a conclusion that sidestepped accountability in favor of bureaucratic ambiguity.

But this isn’t just a story of racial silence or institutional cowardice. It’s a story about power—how Chief James McCann used the color of law not to protect the public, but to intimidate it. He leveraged his position to retaliate against fellow officers, humiliate subordinates, and control outcomes that served him—not the public interest. He was not just a bad boss. He was a bully with a badge.

What this report exposes is not just one man’s fall from command—it is the system’s refusal to see what it does to those who won’t play along. It’s the culture that makes racism a rumor and retaliation a coincidence. It’s the way silence becomes policy.

To those who continue to suffer in silence: your voice matters.

To those who buried these truths: history remembers.

And to the people of Lorain: this is your police department. Demand better.