One Rule for Them: Lorain Council’s Orchestrated Smear of Garon Petty

It wasn’t just a double standard—it was a setup.

May 07, 2025

By Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, CDCA, LSW (Ret.)

Investigative Writer | Lorain Politics Unplugged

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I. A Setup in the Chamber

It wasn’t just a double standard—it was a setup.

On July 1, 2024, Lorain City Council members and staff triggered a chain of events that led to criminal charges against Garon Franklin Petty—charges that increasingly appear to be the product of political manipulation rather than public safety. The events that unfolded during and after that evening’s city council meeting were not isolated or accidental. They were coordinated, with multiple council members offering testimony that now appears to be both contradictory and rehearsed.

Garon Petty, who is hard of hearing and often speaks loudly as a result, approached the council floor following the meeting’s conclusion, as many residents have done for decades. Despite no physical contact or direct threat being recorded or quoted by any council member or witness, Petty was accused of being threatening. Council members described him as agitated, aggressive, or intimidating. But none could agree on what he actually said—and all offered different accounts of where they were standing and what they saw.

Councilwoman Mary Springowski claimed in an email sent the following morning that Petty was “CLEARLY acting in a highly agitated manner,” and suggested that the livestream was incomplete and that the IT department bore responsibility. Meanwhile, Councilman Tony Dimacchia declared in his own message that Petty’s behavior was “ABSOLUTELY UNACCEPTABLE” and accused him of threatening staff. Yet when pressed, none of the members could consistently recount the same version of events.

That evening, the council livestream cut out early, and much of what happened after the meeting remains undocumented by city video. This absence of audio footage has allowed a wave of speculation, hearsay, and contradictory written accounts to take hold as pseudo-evidence. These contradictions matter. They are the cracks through which the truth emerges.

More troubling is the rapid escalation from awkward post-meeting engagement to a full-blown criminal complaint. Less than 24 hours after the incident, Lorain Police Chief James McCann emailed council saying, “An investigation has already been ordered and will start this morning.” The statement was definitive—an investigation was not requested, it was ordered. But by whom?

According to testimony and emails later obtained and reviewed, Chief McCann was not even at the meeting. His directive followed pressure from Springowski, Dimacchia, and others—council members who had, by that point, already begun framing Petty’s conduct as criminal. The rush to investigate was not organic. It was institutional.

It’s also important to note that this wasn’t the first time Petty had addressed council assertively. He had attended meetings before, including ones involving contentious topics like public records, discrimination, and ethics. What changed this time was the narrative.

Council members collectively redefined his tone, his presence, and his posture as a threat.

Petty’s hard-of-hearing status was never meaningfully accounted for. In fact, it seems it was used against him. His louder speech patterns, combined with his physical stature, were interpreted as aggression despite his physical distance—estimated between 15 to 20 feet by some witnesses. Notably, no one quoted Petty verbatim, and no specific threat was identified. What they reported instead were feelings—how they felt. But feelings, no matter how strongly held, are not facts.

The result was a prosecution not based on evidence, but on perception. And that perception was shaped and shared among council members in real time, in what increasingly appears to have been a coordinated effort to remove and discredit a citizen critic. This setup, masked as security enforcement, should alarm every resident of Lorain who values transparency and public access.

This wasn’t a matter of public safety. It was a matter of political performance. And the evidence, once examined, doesn’t just raise questions—it provides answers. Someone wanted Garon Petty silenced. And they almost succeeded.

Almost.

II. Contradictions and Conflicts

From the earliest emails sent after the July 1 incident, contradictions between council members and staff began piling up. The accounts of who was where, who felt what, and what was actually said by Garon Petty differ so significantly that they cannot all be true. These contradictions matter not just for their factual content, but for what they reveal about a politically motivated narrative being sculpted after the fact.

Tony Dimacchia wrote that Petty entered a “clearly posted area for council members” and claimed Petty “yelled at our Clerk’s name not out loud but directly at her.” His account goes on to state that Petty “should never have to be escorted out,” but fails to note that no physical contact occurred, and no officer was present to escort him. Springowski, in her version, claimed she was ready to have the matter received and filed—until Petty allegedly escalated. She also thanked Dimacchia for his “honesty,” a curious statement given the clear inconsistencies between their two recollections.

One of the most glaring issues is that no single witness could definitively recount what Petty actually said. Not a single quote is provided by any councilmember. Councilman Joel Arredondo even admitted under questioning that he was not wearing his hearing aids that day and could not clearly hear Petty.

That raises the question: how can someone be charged with disorderly conduct or threatening language if no witness can identify what was said?

Then there is the physical inconsistency. Dimacchia claims Petty was “as far back as six feet,” while others suggest he was closer to 20 feet away. The location of each council member also seems to shift depending on the version of events. Mary Springowski claimed the incident happened before the meeting had ended, yet others described it as occurring once proceedings were over. Timing matters in a case hinging on whether Petty was unlawfully in a restricted area.

The decision to label the area “restricted” only gained traction after this incident. Historically, the council floor has been accessible before and after meetings. It was common for residents and even former city employees to approach council to discuss issues or follow up on concerns. No formal signage, barriers, or law enforcement presence ever enforced that restriction—until now. This suggests the rule was created retroactively to justify the charges.

Adding to the confusion is the fact that Springowski, Dimacchia, and others later recused themselves as witnesses. This included Law Director Patrick Riley, who helped facilitate the investigation and later had to withdraw because of his own involvement in the decision-making. If these individuals were conflicted enough to withdraw as witnesses, their actions and influence at the beginning of the process should also be viewed as compromised.

Dull herself originally filed paperwork expressing her desire to press charges. She later receded from that role. Lt. Jacob Morris, who was “ordered” by Chief McCann to investigate, eventually became the primary complainant. This raises ethical concerns. If the person allegedly threatened is no longer the complainant, why are these charges being pursued at all?

(McCann is currently on Leave for suspected retaliatory ethical violations towards officers and citizens and using racial slurs.)

The substitution of Morris as the complaining witness and the law department’s recusal leave a vacuum of legitimate testimony. What remains is a stack of inconsistent, vague, and politically motivated narratives that cannot stand up to legal scrutiny. What they do stand up to, however, is the city’s long-standing desire to silence dissent—especially when it comes in the form of public records demands, legal challenges, or vocal criticism.

Inconsistencies don’t just weaken a criminal case. They expose intent. The more this case is examined, the more it resembles a constructed narrative—engineered not to ensure safety, but to neutralize a perceived political nuisance. And in Lorain, that appears to be more than enough reason to bring out the handcuffs.

III. Missing Footage, Missing Fairness

Perhaps the most glaring vulnerability in the city’s case is the absence of any complete video or audio record. The livestream footage of the July 1 meeting cuts out before the disputed interaction took place. This technological failure has created an evidence vacuum—one that council members and law enforcement have filled with speculation and hyperbole. The city has failed to release a full, synchronized account of the incident from surveillance or council chamber footage, further undermining their claims.

Mary Springowski acknowledged this failure outright. In her internal email, she stated, “The livestream and recording failed,” and added that IT was responsible. That admission is crucial—it confirms that any video presented as evidence does not contain the full event. This means that the claims of Petty shouting, gesturing, or moving aggressively cannot be verified through video. Yet multiple council members continue to assert that the evidence supports their claims.

Arredondo’s later statements contradicted these assertions. During his interview, he acknowledged that he did not hear Petty clearly and was experiencing issues with his hearing aid. “I did not hear the shouting because of all this other conversation,” he said. Arredondo also made clear that he didn’t know whether Petty had been invited into the space, or what exactly he said. This is critical. A charge of disorderly conduct or criminal trespass relies on both action and intent. If no one can confirm the content of Petty’s words, and the video cuts off before the alleged incident, what exactly is being prosecuted?

Meanwhile, Councilman Dimacchia’s account—submitted in writing—stated that Petty yelled Dull’s name “at the top of his lungs,” but again failed to quote any specific threat. He simultaneously admitted that Petty did not come closer than six feet, a distance hardly consistent with physical menace. Moreover, he blamed Dull for not diffusing the situation, writing, “I’m disgusted at Bre for not stepping up.” That doesn’t sound like a man convinced she was in danger—it sounds like a scapegoat strategy for a spectacle council members couldn’t control.

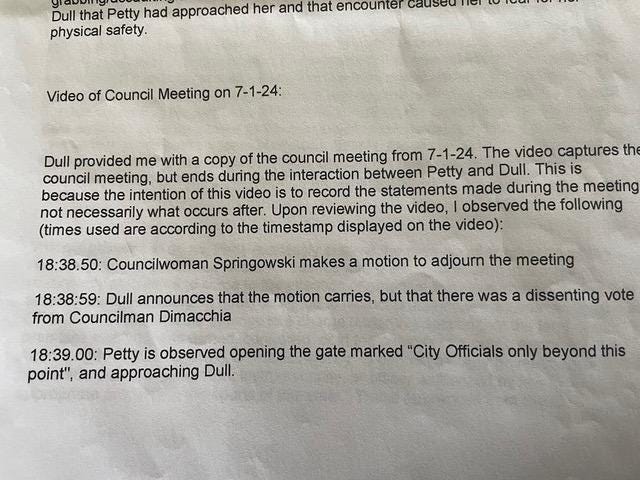

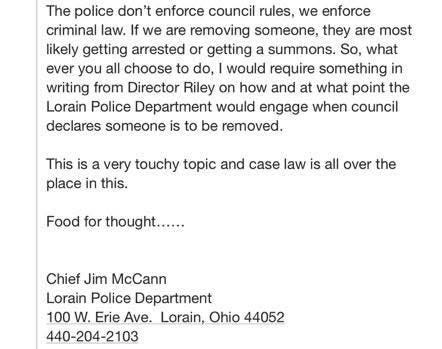

The inconsistency extends to how council handled the aftermath. Chief McCann’s first internal response shows hesitation, not urgency. In his initial email to council, McCann wrote: “The police don’t enforce council rules… we enforce criminal law,” and acknowledged legal uncertainty: “This is a very touchy topic and case law is all over the place on this.” He requested written legal guidance before taking any action. This suggests he understood the line between council protocol and criminal law—and wanted to avoid crossing it.

Yet that caution was short-lived. Hours later, McCann sent a follow-up stating that “an investigation has already been ordered and will start this morning.” What changed? The most likely answer is political pressure. The first email leaked. The second launched a formal probe. This rapid shift from legal restraint to prosecutorial action suggests McCann was not acting based on evidence—but based on politics.

Also notable is the selective distribution of that evidence. Lt. Morris hand-delivered the entire file—including audio—to me as a journalist, stating, “Chief told me to give it to you… we [he] know you will put it online.” This raises an obvious question: if the city believed Petty’s conduct posed an actual danger, why would they hand the evidence to the press rather than to his legal counsel first? The likely answer is that city leadership hoped to embarrass Petty, and perhaps even other council members, rather than achieve justice.

The narrative being advanced is not only unsupported by evidence—it’s strategically designed to survive without it. By flooding the record with conflicting statements, dramatized emails, and vague witness accounts, the city has insulated itself from scrutiny. They’ve created just enough chaos to press forward with charges while evading the burden of proof. In the absence of footage, they’ve weaponized fear.

In Lorain, it appears that due process is secondary to damage control. And when the truth is inconvenient, it’s easier to bury it beneath broken streams, lost recordings, and contradictory claims than to admit you overreacted. The missing footage isn’t just an IT error—it’s the cornerstone of a cover-up dressed as caution.

IV. The Substitution and the Silence

One of the most telling developments in this case is the shift in who is listed as the official complainant. Originally, according to the police report authored by Lt. Jacob Morris, Clerk of Council Breanna Dull signed both an affidavit and a complaint form. Morris writes: “Dull advised me that she was interested in pursuing any applicable charges against Petty.” Yet, when charges were filed with the Lorain Municipal Court, Dull’s name was absent. The complainant listed was Morris himself.

This raises immediate red flags about the integrity of the process. If Dull truly believed she was in danger, and her affidavit was sufficient, why was she replaced? The removal of her name not only diminishes the claim that she was a victim in need of protection—it also opens the door to serious procedural questions about why a law enforcement officer who wasn’t present at the event assumed the role of complainant.

Dull’s initial position in the case allowed city officials to frame the charges as a matter of staff safety. Once she stepped back, however, they were left scrambling for legitimacy. Having a police officer file the charges maintained the optics of authority—but it also changed the nature of the case. It moved from a victim-led complaint to a city-led prosecution. And that transformation underscores the political calculations at play.

This maneuver is compounded by the fact that other central figures—Law Director Riley, Councilman Dimacchia, and Councilwoman Springowski—all tried to recuse themselves as potential witnesses. This trio of initial complainants and strategists were instrumental in pushing for an investigation. Their eventual withdrawal suggests they knew their involvement might jeopardize the legal case, if not ethically compromise it.

Meanwhile, the city’s internal narrative continued to evolve. In a subsequent police report, Morris cited ORC 2921.03—Intimidation of a Public Servant—and stated that Petty’s behavior constituted “a felony of the third degree.” He referenced procedural disruptions, security changes, and physical fear experienced by Dull. Yet none of those claims included a specific quote, threat, or contact. Everything revolved around what was inferred or believed—not what was done.

This gap between subjective fear and objective evidence is dangerous. Legal scholar and public records advocate Frank LaRose has warned against what he calls “weaponized perception”—the act of converting discomfort into prosecution. That appears to be precisely what’s unfolding in Lorain. Council and law enforcement are crafting a case based on interpretations, not actions. And when interpretations shift based on political needs, justice becomes fluid.

Further complicating the issue is the city’s failure to provide full discovery to Petty’s defense. Despite having handed materials to this journalist for public release, the city has claimed that some portions of evidence remain privileged or incomplete. This creates a two-tiered system: the court gets one story, the press gets another, and the accused is left navigating both. Transparency, ironically, is being selectively distributed.

All of this reinforces the conclusion that this case is not about enforcing laws—it’s about preserving power. Petty asked questions. He challenged public officials. He demanded public records. That, more than anything he may have said or done, seems to be the true cause of the city’s response.

If the complaint against him had any merit, it would not have required this level of narrative reshaping, personnel substitution, or internal contradiction. The facts would have spoken for themselves. Instead, the silence of the original complainant and the substitution of political actors speaks volumes

The legal system is supposed to apply evenly. But in Lorain, the application depends on politics, not principle. The rules are enforced not by what is done, but by who does it. And if you’re not on the right side of that equation, the consequences aren’t just different—they’re manufactured.

This is not equal justice. This is political theater wrapped in a badge.

VI. Final Thought: Prosecuted Not for Threats, But for Challenging Power

From the start, the case against Garon Franklin Petty was never about criminal trespass or disorderly conduct. It was, and remains, a calculated effort to punish political dissent by rewriting custom, inflating fear, and abandoning the public’s right to access and speak freely inside a public building. What began as a simple confrontation over records and transparency has spiraled into a legal offensive that now threatens the legitimacy of city leadership and the constitutional balance of public engagement in Lorain.

Key to this narrative is the police report authored by Lt. Jacob Morris, which frames Petty as a credible physical threat despite the absence of any recorded threat, contact, or weapon.

Morris writes that Petty’s actions caused “operational changes” to the Office of the Clerk of Council, including a police escort for Breanna Dull, altered office access, and permanent security presence at meetings. Yet these extreme responses were based on subjective feelings, not documented actions.

Notably, Dull initially signed complaint forms and an affidavit—but she is no longer the official complainant in the case. That role was assumed by Morris himself, in what can only be interpreted as a political pivot after initial momentum stalled.

This substitution is not a minor detail—it reveals the city’s shifting strategy to preserve a shaky case. Dull, despite allegedly fearing for her safety, is no longer on the record as the accuser. Instead, a high-ranking officer with no direct involvement becomes the legal backbone of the prosecution. Why the change? The likeliest answer is that city officials realized putting Dull on the stand would expose contradictions between her emails, her internal role in political coordination, and the actual events of that evening. So, they took the safest option: remove her name, keep the story.

These contradictions are especially glaring when viewed against statements from other councilmembers. In one email, Mary Springowski called Petty “CLEARLY highly agitated,” yet admits the livestream failed and the video was incomplete. Arredondo later testified that he didn’t hear what Petty said at all and had issues with his hearing aid. Dimacchia, who demanded action “against Mr. Petty,” later admitted Garon stood “as far back as six feet” and never crossed into direct confrontation. It seems everyone saw something—but no two people saw the same thing. What they shared was a political motive, not factual consistency.

Chief James McCann’s email on July 2, 2024, further complicates the city’s narrative. In a message to councilmembers obtained by this publication, McCann warned that officers “do not enforce council rules… we enforce criminal law,” and that removing someone based solely on a councilmember’s discomfort is legally dubious. “This is a very touchy topic and case law is all over the place on this,” McCann wrote. He requested written guidance from Law Director Riley on what actions police could lawfully take. Yet just hours later, he reversed himself entirely, writing that an investigation had already been “ordered and will start this morning.” That about-face suggests coordination—not caution—was driving city policy.

Meanwhile, the city has withheld portions of discovery in this case, even as Lt. Morris hand-delivered full audio files and materials to this journalist with the explanation, “Chief told me to give it to you… we [he] know you will put it online.” That admission, captured in person, shows the weaponization of transparency not for accountability, but as a pressure tactic. It raises the disturbing possibility that officials hoped to embarrass councilmembers publicly while maintaining the appearance of internal discipline. It also suggests an extraordinary level of access granted to a reporter—likely because the evidence wouldn’t hold up in court.

Context matters. For decades, Lorain residents, including elected officials and activists, have been permitted to approach the council floor before and after meetings. That informal tradition, grounded in Ohio’s Sunshine Laws (ORC 149.43 and 121.22), has promoted open dialogue and civic oversight. There were no physical barriers, no arrests, and no signs warning citizens away that carried enforceable Ohio Revised Code citations.

While a sign barring access to the council floor existed, it lacked legal force and was widely ignored after meetings concluded. Councilmembers and residents alike commonly crossed into the area to follow up on issues, ask questions, or converse informally. The existence of the sign did not change the custom, and no councilmember cited it until it became useful for justifying Petty’s removal.

In their current narrative, city officials now claim the meeting had not officially concluded because it had not been gaveled closed—even though a motion to adjourn had already been made. According to Ohio legal practice and Roberts Rules of Order, the gavel is symbolic. The legal act of adjournment occurs when the body adopts the motion. Thus, Petty entered the chamber during a period that—by law and practice—should have been considered open.

It was only after Petty, a man who is hard of hearing, stepped onto the floor post-meeting to seek answers about records that council abruptly chose to invoke the sign, change the rules, and call the police. That’s not enforcement—that’s targeting.

Adding insult to injury, Jayne Morales—a resident—disrupted council meetings in the past with far more volume, direct confrontation, and even a return visit. Yet Morales was never investigated, never arrested, and never charged. The difference in treatment is stark and inescapable. When a powerful narrative suits their needs, councilmembers demand action. When it doesn’t, they dismiss it as free speech. To be clear, we are not suggesting that Morales should have been prosecuted. Her conduct, though disruptive, is protected under the First Amendment. The point is that Petty’s conduct was no more egregious—yet he alone faced a police investigation and criminal charges. This selective enforcement reveals a double standard driven by political discomfort, not public safety. This arbitrary approach to public decorum threatens not just due process, but the legitimacy of the council’s own governance.

The result is prosecution by convenience. Garon Petty didn’t commit a felony. He didn’t make a threat. What he did was challenge authority—loudly, visibly, and inconveniently. In doing so, he triggered a political immune system that reacted not to protect the public, but to punish the challenger. If this prosecution moves forward, it will not just convict a man for entering a public meeting space. It will enshrine fear, bias, and retaliation into Lorain’s civic identity—and send a clear warning to every resident who dares to speak too forcefully to power.