Follow the Money: How a Tight Donor Network, Interlocking Campaigns, and a Seven-Figure City Contract Converge in Lorain

Introduction: This Is Not About One Candidate or One Contract

This story is not about a single campaign contribution, a single election cycle, or a single municipal contract viewed in isolation. It is about what becomes visible only when public records are read the way the law intended them to be read together, across time, across offices, and across actors. Campaign finance reports are intentionally mundane. They are standardized, repetitive, and procedural. They are meant to disclose, not to persuade. Most are skimmed, filed away, and forgotten. That is precisely why they become powerful when examined collectively.

When dozens of these filings are placed side by side, across multiple years and across multiple candidates who occupy different positions within the same local government, patterns begin to surface that cannot be dismissed as coincidence or noise. What follows is a document-driven examination of a political ecosystem in Lorain, Ohio, revealed through the candidates’ own sworn disclosures. It traces how a relatively small and recurring donor network, a web of interlinked political committees that financially support one another, and a seven-figure professional services contract awarded to Coldwater Consulting all exist within the same structural space.

This is not a narrative built on rumor, inference, or anonymous sourcing. It is built entirely from public records that candidates and committees are legally required to file, certify, and stand behind under penalty of election falsification pursuant to Ohio Revised Code 3517.10, as well as from ordinances and contracts formally adopted by the City of Lorain through its legislative process. No allegation of criminal conduct is made here. No motive is assigned to any donor, candidate, or public official. The documents do not need embellishment to be meaningful. They speak for themselves.

The role of this reporting is not to accuse, but to assemble, to contextualize, and to make visible what is otherwise fragmented across dozens of filings that are rarely read together. The central question raised by this record is not whether the structure it reveals is legal. For the most part, it is. Ohio law permits campaign contributions, allows committee-to-committee transactions, authorizes professional services contracts, and relies on disclosure as the primary safeguard against abuse. The more difficult and more important question is whether a system that concentrates political financing, reinforces itself through interconnected committees, and overlaps so closely with the administration of major public contracts is acceptable, genuinely transparent, and worthy of public trust.

That question does not belong to the courts. It belongs to the public.

The Coldwater Consulting Contract: The Public Money Side of the Ledger

This is the fulcrum of the story, because Coldwater Consulting does not appear in Lorain’s records as a one-time consultant brought in for a discrete task. The record shows something closer to institutionalization. In December 2025, Lorain City Council adopted Ordinance 193-25, authorizing the City to enter into a professional services agreement with Coldwater Consulting, LLC for management of the Black River Dredge Material Reuse Facility. The approved amount was $1,046,301.18, paid from the Dredge Fund and structured as a time-and-materials contract with built-in administrative flexibility and renewal potential.

That decision matters not only because of the dollar figure, but because of what the ordinance does procedurally. Council did not simply approve an invoice or a short-term engagement. It enacted legislation authorizing an ongoing professional services relationship for a core piece of the City’s environmental infrastructure. The contract governs facility management, engineering oversight, regulatory compliance, and operational coordination tied to dredge material reuse. In practical terms, it embeds Coldwater Consulting inside the City’s dredge program rather than treating it as an external, episodic reviewer.

The structure of the agreement reinforces that point. While the City Engineer and executive administration retain formal oversight, the contract allows internal reallocations of task budgets without returning to City Council so long as the overall contract ceiling is not exceeded. That means meaningful changes in how more than one million dollars is spent can occur administratively rather than legislatively. Oversight exists on paper, but it is internal and discretionary rather than public and deliberative.

Under Ohio law, professional services contracts are exempt from competitive bidding requirements. That exemption is lawful and well established. Engineers, planners, and specialized consultants are often selected through qualifications-based processes rather than low-bid competition. But that legal structure carries an implicit tradeoff. When price competition and side-by-side comparison are removed by design, the system relies more heavily on transparency, independence, and public confidence in the decision-makers exercising that discretion.

What raises legitimate concern here is not simply that Coldwater Consulting received a seven-figure contract. It is that the City appears to have moved beyond repeated engagement into something closer to codification. When Council passes an ordinance authorizing a long-term, renewable professional services arrangement for a function as central as dredge management, it is effectively signaling that this vendor is part of the City’s permanent operating framework. That is a significant policy choice, not a routine administrative act.

Viewed in isolation, Ordinance 193-25 can be defended as a practical response to a complex environmental responsibility. Viewed alongside the campaign finance record, it takes on additional weight. The same period in which Coldwater Consulting and individuals associated with it appear as repeat political donors is also a period in which the City formalizes and entrenches that consulting relationship through legislation rather than ad hoc contracting.

That does not prove impropriety. It does not establish a quid pro quo. It does, however, heighten the importance of scrutiny. Codifying a long-standing vendor relationship through ordinance is a powerful act. Doing so in a political environment where donor networks, interlinked committees, and elected officials are tightly connected invites reasonable questions about independence, influence, and whether sufficient distance exists between political support and public decision-making.

The Campaign Finance Records: The Political Money Side of the Ledger

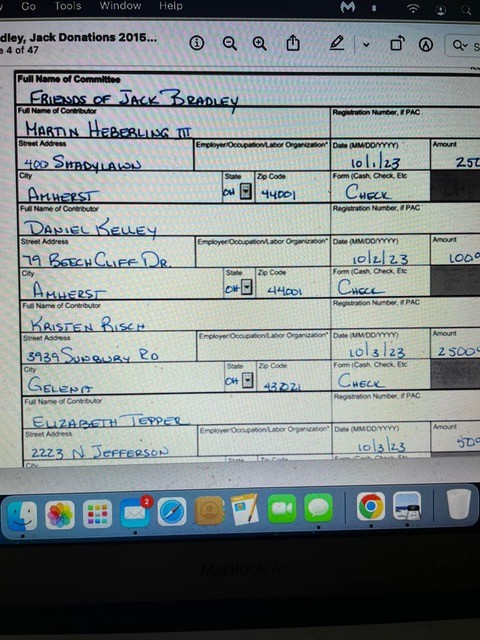

Between 2021 and 2023, campaign finance reports were filed for a wide range of Lorain candidates and political committees, including Jack Bradley, Joshua Thornsberry, Tony Dimacchia, Mitchell Fallis, Mary Springowski, Terri Soto, Joel Arredondo, Victoria Kempton, Cory Shawver, Beth Henley, Dan Nutt, and Kyriece Brooks. Read individually, each filing looks ordinary. Read together, they reveal a dense and repeating financial pattern that is central to understanding how political power is financed and reinforced locally.

The first and most striking feature is donor repetition, not just across cycles but across offices. The same individual donors appear again and again on different committees’ reports, often within the same reporting period and sometimes on the same dates. These are named individuals with listed addresses in Lorain, Amherst, and surrounding communities, writing checks that range from several hundred dollars to high-dollar local contributions that approach the upper end of what is typical for municipal races. In several filings, these contributions cluster tightly around key pre-primary or pre-general reporting windows, indicating coordinated fundraising rather than sporadic civic participation.

These donors do not confine their giving to a single candidate. A donor who appears on a mayoral filing often appears again on council filings, sometimes multiple council filings, and sometimes again in later cycles. The effect is cumulative. While no single contribution dominates a race, the repeated presence of the same donors across multiple campaigns creates a durable base of political support that travels with candidates as they move through offices or exercise authority.

The second repeating feature is organizational consistency. The same political organizations and affiliated groups recur across filings, including party-aligned clubs and labor organizations. Their participation is lawful and disclosed, but their repetition matters. It reinforces the reality that these campaigns operate within a relatively small, stable political universe. The donor pool is not expanding outward. It is circulating inward.

The third feature, and the one most often overlooked in local reporting, is committee-to-committee financial interaction. Multiple filings show campaign committees paying other campaign committees for fundraiser tickets, sponsorships, or event participation. These transactions are disclosed on Statements of Expenditures using Forms 31-B and 31-F, with dates, check numbers, and stated purposes. This is not informal networking. It is money moving between political entities.

When one candidate’s committee purchases tickets from another candidate’s committee, the effect is twofold. Money stays within the same political circle, and political alignment is reinforced financially. Campaigns are not just supporting one another rhetorically or ideologically. They are subsidizing one another’s fundraising efforts. Over time, this creates a web of mutual financial reinforcement that is fully lawful but rarely acknowledged as such.

This structure is critical to understanding why Coldwater-linked donations cannot be evaluated narrowly. Even where individuals directly associated with Coldwater Consulting do not appear as donors on a particular candidate’s report, the network still reaches that candidate indirectly. Donors who give to Coldwater-aligned candidates also give to others. Committees that receive Coldwater-aligned donations also financially support other committees. The money does not move in straight lines. It moves through relationships.

The Bradley Problem: Where Structure, Discretion, and Hypocrisy Collide

No individual better illustrates the convergence of political money, discretionary authority, and institutional contradiction than Mayor Jack Bradley. Across the campaign finance filings reviewed, Bradley is the recipient of the highest concentration of donations from individuals tied to the same donor ecosystem that includes Coldwater Consulting and its principals. This is not an incidental observation. It is a documented pattern. When the filings are read together, Bradley emerges not merely as a participant in the network, but as one of its primary beneficiaries. That fact alone would merit scrutiny given his position as the City’s chief executive. What elevates it from notable to troubling is how that financial support intersects with the specific discretionary decisions Bradley has made while in office.

As mayor, Bradley exercises extraordinary unilateral authority over the City’s legal representation and the expenditure of public funds for outside counsel. Under Lorain’s structure, the Mayor and the Safety–Service Director possess the ability to approve contracts for legal services below certain monetary thresholds without prior Council approval. That authority exists to allow the City to function efficiently, not to insulate politically sensitive decisions from scrutiny. Yet it is precisely within this discretionary space that Bradley authorized outside legal representation for codefendants in ongoing litigation, including Police Chief James McCann, while Bradley himself is a named codefendant in the same matter.

This is not a minor procedural concern. It goes to the heart of public fiduciary responsibility. In civil litigation where public officials are sued in their official capacities, Ohio law provides a framework for indemnification and representation precisely to avoid conflicts of interest and self-dealing. The default expectation is that the public entity either defends its officials collectively through established legal channels or clearly documents why separate counsel is necessary. What occurred here was neither routine nor neutral. Bradley participated in decisions to expend city funds on outside counsel for fellow defendants in litigation in which he himself has a direct personal and legal stake, doing so through discretionary mechanisms designed to bypass public debate.

The optics alone are indefensible. But the issue is not optics. It is structure. Bradley, as a political actor deeply embedded in the donor network documented in this reporting, exercised unilateral executive discretion to direct taxpayer funds toward legal representation that directly benefits his codefendants and, by extension, his own litigation posture. That same Bradley accepted substantial campaign support from individuals within the same political ecosystem. This does not require an allegation of quid pro quo to be alarming. It requires only an honest accounting of power.

The hypocrisy becomes impossible to ignore when viewed alongside Bradley’s public posture. The same administration that speaks frequently about fiscal responsibility, transparency, and ethical governance made decisions about legal spending behind closed doors, using mechanisms specifically designed to avoid legislative scrutiny. The same mayor who benefits most directly from a tight donor network also presides over a system in which discretion is exercised to protect insiders while the public is told to trust the process. Trust, however, is not a substitute for accountability, and discretion is not a license to act without consequence.

What makes this especially corrosive is that the decision to hire outside counsel was not compelled by emergency, novelty, or necessity. McCann, as a city official, should have been indemnified through standard channels if the City believed his actions were within the scope of employment. If the City believed they were not, that determination itself should have been made transparently and independently, not through executive fiat by a fellow defendant. Instead, Bradley approved legal expenditures in a context where any reasonable observer would recognize a conflict between his duty to the public and his personal interest in the outcome of the litigation.

This is where campaign finance stops being abstract and becomes operational. A mayor who is financially sustained by a narrow donor network, who governs within an ecosystem of mutual political reinforcement, and who then uses discretionary authority to shield fellow insiders from legal exposure with public funds is not merely exercising judgment. He is revealing the priorities of the system that sustains him. The issue is not whether any particular check “bought” any particular decision. That is the wrong question. The correct question is whether a governance structure that concentrates political support and discretionary power in the same hands can plausibly police itself.

Jack Bradley’s situation crystallizes the central thesis of this reporting. When political money and public authority circulate within the same closed network, the risk is not overt corruption. The risk is normalization. Decisions that should trigger alarms instead become routine. Conflicts that should prompt recusals instead become administrative details. And actions that would be unacceptable if performed by an outsider are quietly justified when performed by someone firmly inside the circle.

This is not about one mayor. It is about what his conduct makes visible. Campaign finance disclosures show who sustains political power. Contracting and legal spending decisions show how that power is exercised. When those two ledgers are read together, the problem is not subtle. It is structural.

Inter-Committee Transfers: How the Network Reinforces Itself

Committee-to-committee spending is one of the most structurally significant, and least examined, mechanisms through which Lorain’s political financing system reinforces itself over time. On paper, these transactions appear routine. One campaign committee purchases fundraiser tickets from another committee. A committee sponsors an event hosted by another candidate. Each entry is disclosed, itemized, and lawful under Ohio campaign finance law. Viewed individually, they are easy to dismiss as ordinary political networking. Viewed collectively, across multiple cycles and multiple offices, they reveal a system designed to circulate money internally rather than expand participation outward.

The practical effect of this structure is that funds raised by one campaign do not meaningfully leave the political ecosystem in which they were generated. Instead, they move laterally among aligned campaigns, reinforcing the same set of candidates and committees who already share donor bases, consultants, and political relationships. Money raised from a limited pool of repeat donors is recycled through sponsorships, ticket purchases, and shared fundraising events, multiplying its political impact without requiring new public support. This is not incidental. It is how political viability is sustained within a closed system.

This circulation does more than preserve resources. It hardens alignment. When campaigns financially support one another, the relationship ceases to be merely ideological or partisan and becomes materially reciprocal. Financial support creates expectation, access, and durability. A campaign that buys fundraiser tickets for another campaign is not simply showing solidarity. It is investing in a relationship that is likely to be returned, directly or indirectly, in future cycles. Over time, this produces a web of mutual dependence that binds candidates together financially long after a single election has passed.

What makes this structure especially consequential is its interaction with donor repetition. When the same donor cluster feeds multiple committees, and those committees then use their funds to support one another, the system begins to function as a closed loop. Donor money enters the loop, circulates internally, and reinforces the same political actors across offices and years. The effect is cumulative. Political capital compounds. New entrants face higher barriers, not because of voter preference alone, but because financial infrastructure is already concentrated and self-sustaining.

None of this is hidden. Every transaction is disclosed. Every payment is recorded. That transparency, however, is only meaningful if the records are read together. When committee-to-committee transfers are examined in isolation, they appear trivial. When they are examined as part of a larger pattern that includes recurring donors, shared fundraising calendars, and coordinated campaign activity, they reveal a political system that increasingly insulates itself from external challenge and broader public engagement.

This is why legality is not the end of the inquiry. Ohio law permits these transactions, but it does so on the assumption that disclosure will allow the public to evaluate their impact. The concern is not that committee-to-committee spending exists. The concern is that, over time, it contributes to a governance environment in which political power is reinforced internally, recycled among familiar actors, and increasingly detached from a wider base of civic participation.

This structure does not require secrecy to be effective. It requires only repetition. And repetition is exactly what the record shows.

Loans and Financial Dependence

Campaign loans further tighten and stabilize the same political structure revealed elsewhere in the record. Ohio law permits candidates and committees to rely on loans, whether from the candidates themselves or from individuals closely associated with their campaigns. These arrangements are lawful and commonly used, but they differ in kind from ordinary contributions in a way that is both deliberate and significant. A contribution is complete when it is made. A loan is not. It creates an ongoing financial obligation that does not end on election night and can extend well into a candidate’s term in office.

Several of the campaign finance filings reviewed show loan balances that persist into subsequent reporting periods, meaning the financial relationship between the officeholder and the lender remains active after the election has concluded. This distinction matters. A campaign funded primarily by small, dispersed donations reflects broad participation and minimal post-election entanglement. By contrast, a campaign sustained through loans and concentrated high-dollar contributions reflects a narrower financial base and a higher degree of dependence on a limited set of individuals. That structure is not prohibited, but it carries different implications for transparency and accountability.

Loans also introduce an element of temporal leverage that ordinary contributions do not. Until a loan is repaid or forgiven, the obligation continues to exist, and with it, a continuing financial relationship. Ohio law requires these obligations to be disclosed precisely because they persist beyond the campaign itself. The statute recognizes that voters are entitled to know not only who supported a candidate during an election, but who remains financially connected to that candidate while they are exercising public authority.

This does not establish improper conduct, nor does it imply that any particular decision was influenced by a loan or lender. What it does is heighten the importance of transparency and public awareness. When candidates who relied on loans or highly concentrated funding later exercise governmental authority over contracts, appointments, zoning decisions, or discretionary spending, the public has a legitimate interest in understanding the financial structures that helped place them in office. That interest exists regardless of intent. It flows directly from the continuing nature of the financial relationship itself.

Ohio’s disclosure framework anticipates this concern. It does not forbid loans. It requires them to be visible, detailed, and traceable so that the public can assess how financial dependence may intersect with the exercise of public power. When these disclosures are read together with donor repetition, inter-committee transfers, and long-term professional relationships with municipal vendors, they become part of a larger picture of how political viability is financed and maintained over time. Transparency does not presume wrongdoing. It provides the context necessary for informed judgment, which is exactly what these records were created to support..

Why This Matters for Governance, Not Just Elections

Elections determine which names appear on the oath of office, but campaign finance determines something far more consequential and far less visible: who is able to mount a viable campaign in the first place, who can sustain that campaign through multiple reporting periods, and who enters public office already embedded within an existing political and financial architecture. When the same donor networks, political committees, consultants, and institutional supporters recur not merely within a single election cycle but across years, offices, and levels of authority, governance itself begins to mirror the structure that financed it. Decision-making does not occur in a vacuum, and it does not begin on Election Day. It occurs within a context shaped by repeated financial reinforcement, shared fundraising infrastructure, and long-standing political alignment that predates any single vote, ordinance, or contract authorization.

Over time, this produces more than continuity in officeholding. It produces continuity in influence, access, and perspective. The same voices are heard first, often without being recognized as such. The same relationships are treated as routine rather than consequential. The same assumptions about who is credible, who is serious, who is “inside,” and who can be safely ignored become embedded in the daily operation of government. This is not the result of one improper act or one tainted decision. It is the cumulative effect of repetition. The risk is not that a single vote is compromised or that one action crosses a bright legal line. The risk is structural insulation, a governing system that becomes progressively less responsive to the broader public because it is increasingly sustained by, oriented toward, and implicitly accountable to a narrow and familiar network that finances political survival. That is the distinction Ohio’s disclosure laws are designed to expose, and it is why campaign finance is not merely an electoral issue. It is a governance issue at its core.

See all the Campaign Finance Files I currently Have and used for this story here: https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:VA6C2:5b17f607-e0e1-41a5-b615-aa876af48c8d

What This Story Does Not Claim

This story does not allege bribery, nor does it assert the existence of any quid pro quo or accuse any individual, campaign, or company of criminal wrongdoing. It does not speculate about intent, nor does it attempt to assign motive where the public record does not require one. What it does instead is document structure. It assembles records that already exist, records that candidates and committees are legally required to file and certify under oath, and places them into a single, coherent context so they can be evaluated as a whole rather than as isolated fragments. The significance of these records does not arise from any one contribution, contract, or decision, but from their repetition, proximity, and intersection over time. That is the distinction that matters. This is not an exercise in accusation. It is an exercise in transparency, grounded entirely in the documentary record the law itself compels into existence.

Why Public Scrutiny Is the Point

Public scrutiny is not an act of hostility, nor is it an insinuation of wrongdoing. It is the mechanism by which democratic systems are meant to protect themselves from insulation, complacency, and the quiet concentration of influence. Ohio’s campaign finance laws are not structured around the assumption that corruption is inevitable. They are structured around the recognition that power, left uninterrogated, tends to consolidate. That is why disclosure exists. Campaign finance reports are not ceremonial paperwork, and they are not intended to be filed, archived, and forgotten. They are intended to be read together, compared across time, and understood in relation to the public decisions made by the officials they help place in office.

When those reports are examined collectively rather than in isolation, they begin to tell a story that no single filing can convey on its own. They reveal who consistently has access to the political process, which donor networks recur across campaigns and offices, how financial support is reinforced through interlocking committees, and how political viability is sustained cycle after cycle within a relatively closed ecosystem. That story is not speculative. It is documentary. It emerges directly from the sworn disclosures candidates submit under penalty of election falsification, and it exists whether or not anyone chooses to look at it.

In Lorain, that story is now visible with unusual clarity. The convergence of recurring donor clusters, inter-committee financial support, and long-standing professional relationships between elected officials and major municipal vendors is not hidden. It is plainly documented. What has been missing is not information, but synthesis. Public scrutiny completes that process. It does not distort the record or assign blame. It fulfills the purpose for which these records exist in the first place, allowing the public to evaluate how access, influence, and decision-making are structured within their local government. That is not an attack on the system. It is the system working as intended.

Final Thought: Sunlight Is the Safeguard

Ohio law does not treat conflicts of interest as a matter of personal comfort or political discretion. It treats them as a matter of public trust. That is why indemnification statutes, ethics provisions, and procurement limits exist. They are not technicalities. They are structural safeguards designed to prevent public officials from using the authority of their offices to steer public resources toward themselves, their allies, or their co-defendants when their personal legal exposure is at stake.

The arrangement involving Jack Bradley, James McCann, and outside legal counsel crosses out of the realm of appearance and into the realm of governance integrity. If Chief McCann was entitled to defense under indemnification, then the City’s obligation was to provide that defense through lawful, neutral mechanisms, not through discretionary approvals exercised by officials who themselves are codefendants in the same litigation. If indemnification was not available, the use of public funds to retain outside counsel for a personal defense becomes even more problematic. Either way, the decision point matters.

What cannot be squared with ethical governance is this. The Mayor and the Safety Service Director, both named parties in litigation arising from the same underlying conduct, participated in or authorized the approval of outside legal representation for their co-defendants using city funds, without independent review and without structural separation. That is not a gray area. That is the precise scenario conflict-of-interest law is designed to prevent. Public officials do not get to vote, approve, or administratively green-light expenditures that directly benefit their litigation posture or the defense strategy of those aligned with them in active legal proceedings.

The hypocrisy becomes impossible to ignore when this conduct is viewed alongside the campaign finance record. The same mayor who accepted campaign support from Rosenbaum later presided over, or enabled, the expenditure of public tax dollars to retain Rosenbaum to represent his co-defendant in a personal capacity. Whether the dollar amount fell below an internal approval threshold does not cure the conflict. Threshold authority exists to streamline routine governance, not to bypass ethical constraints when personal legal exposure is involved. Administrative convenience is not a defense to conflicted decision-making.

This is where repeated assurances that “everything was legal” collapse under their own weight. Legality is not established by silence, internal approval, or the absence of immediate challenge. Legality requires lawful authority exercised by disinterested decision-makers. When officials who stand to benefit directly from a decision are the same officials exercising the discretion to approve it, the safeguard has failed, regardless of whether anyone intended wrongdoing.

And that failure does not exist in isolation. It exists within the same political ecosystem documented throughout this record. The same donor networks recur. The same officials reinforce one another through interlocking committees and shared political infrastructure. The same administration that insists campaign contributions do not matter relies on donors and professionals who later appear in positions of paid authority funded by the public. The contradiction is not subtle. It is structural.

Sunlight does not accuse, but it does eliminate plausible deniability. It forces the record to be read whole rather than in pieces, and when that happens, the central issue is no longer whether any single check cleared legally or any single contract was signed properly. The issue is whether public power is being exercised with the independence, restraint, and accountability the law requires, or whether it has become comfortable operating within a closed loop of political support, mutual protection, and discretionary approval.

Ohio law did not design its ethics framework to rely on trust. It designed it to rely on separation, disclosure, and restraint. When those safeguards are bypassed by the very officials they are meant to constrain, the problem is not political. It is institutional.

Sunlight is not a threat to legitimate governance. It is the only thing that distinguishes public authority from private advantage.

Legal and Editorial Disclaimer

This article is published for informational, journalistic, and public-interest purposes only. It is based entirely on publicly available records, including sworn campaign finance filings submitted to the Ohio Secretary of State pursuant to Ohio Revised Code 3517.10, municipal ordinances and contracts adopted by the City of Lorain, and other documents subject to disclosure under Ohio Revised Code 149.43.

Nothing contained herein constitutes legal advice, legal opinion, or legal representation. The author is not acting as an attorney and does not purport to provide guidance on the interpretation or application of law to any specific individual, entity, or set of facts. Readers should not rely on this article as a substitute for advice from qualified legal counsel.

This reporting does not allege criminal conduct, bribery, or quid pro quo by any individual or entity. No motive is imputed, and no inference of intent is asserted beyond what is explicitly documented in the public record. Where legal standards, statutes, or ethical frameworks are discussed, they are referenced for context and public understanding only, not as definitive conclusions regarding legality or liability.

Any analysis of campaign finance, contracting practices, or governmental decision-making is offered as a structural examination of disclosed records and governance processes. The purpose of this article is to assemble and contextualize information that already exists in fragmented form so it may be evaluated by the public as a whole. The conclusions drawn are editorial in nature and grounded in transparency, not accusation.

All individuals and entities mentioned are presumed to have acted lawfully unless and until a court of competent jurisdiction determines otherwise. References to public officials, candidates, donors, consultants, or vendors reflect their appearances in public filings and official actions, not assertions of wrongdoing.

Public scrutiny of disclosed records is not an allegation. It is the mechanism by which democratic accountability functions.