The Hybrid Lawyer Problem

How Sheffield Lake’s long-time law director helped wire multiple municipalities together and is now poised to step into the court that adjudicates them

BYLINE

By Aaron Christopher Knapp

Investigative Journalist and Public Records Litigant

Lorain Politics Unplugged

Introduction: This Is Not a Scandal. It Is a Structure.

This story is not about a crime, a hidden payoff, or a single bad act caught on tape. It is about something more subtle and, in many ways, more dangerous in local government. It is about structure, accumulation, and institutional blindness. It is about what happens when one legal actor remains in place long enough to become the connective tissue between multiple municipalities and the court system they all rely on, and then treats that accumulated power as administratively routine rather than ethically fragile.

By late 2025, David Graves is not a novice lawyer learning the contours of municipal ethics. He is a veteran law director with more than two decades of experience navigating Ohio municipal law, intergovernmental agreements, Sunshine Law obligations, election law disputes, and the political realities of council dynamics. At this stage of a career, ignorance is no longer a plausible explanation. Institutional awareness is not optional. It is the job.

That is what makes the Chronicle-Telegram’s reporting so consequential. In announcing that Graves would resign as Sheffield Lake Law Director to accept a future magistrate role with the Lorain Municipal Court, the article also included a statement from Graves that should have stopped readers cold. He stated that while stepping away from Sheffield Lake, he intended to retain his other municipal legal roles, including his work for Sheffield Village and Avon Lake.

That single sentence is not incidental background. It is the fulcrum of this entire investigation.

Graves knows, or should know, that Sheffield Lake, Sheffield Village, Avon Lake, and Lorain are not isolated legal islands. They are bound together by long term intergovernmental contracts for water, sewer, and shared services. They are bound by mutual aid agreements for police and fire. They are bound by overlapping enforcement mechanisms. And critically, they are bound by a common court of record. Lorain Municipal Court sits at the center of that system, adjudicating cases that arise directly from the very agreements and ordinances Graves has spent decades drafting, interpreting, enforcing, and defending.

This is not theoretical. It is structural reality.

What makes this more troubling is the immediate context in Sheffield Lake itself. In recent months, Graves has been directly involved in some of the most contentious legal disputes the city has faced, including election eligibility challenges and aggressive post election maneuvering aimed at preventing a duly elected council member, Aden Fogel, from assuming office. Graves authored and advanced the legal position questioning Fogel’s eligibility after the election had already been certified. That action did not merely raise abstract legal questions. It had a concrete political effect. Had it succeeded, it would have removed from the council one of the very members entitled to vote on Graves’s replacement as law director.

That fact cannot be brushed aside as coincidence.

At a minimum, it demonstrates a continued willingness to exercise expansive legal authority inside Sheffield Lake at the exact moment Graves was negotiating his own exit and future role. At worst, it reflects a profound lack of sensitivity to how power, timing, and perception intersect. A lawyer with this level of tenure understands how council appointments work. He understands how successor selection works. He understands how removing or sidelining a sitting or incoming council member reshapes that process. Pretending otherwise insults the public’s intelligence.

When these actions are viewed together, the pattern becomes harder to ignore. A long serving law director deeply embedded in the legal infrastructure of multiple municipalities. A public declaration that he intends to carry those roles forward while stepping into the judicial system that serves them. Recent high conflict interventions in Sheffield Lake governance that materially affect who sits on council and who participates in selecting his successor. All of this occurring against a backdrop of closed door executive sessions, Sunshine Law disputes, and growing public distrust.

This is why this story must be told now, and why it must be framed correctly.

This is not about alleging corruption. It is about recognizing that longevity confers responsibility. After twenty plus years in municipal law, Graves knows exactly how intergovernmental systems function and how fragile public confidence can be when lines blur. Choosing to proceed anyway, without visible guardrails or transparency, is not a neutral act. It is a structural decision with consequences.

Before the robe goes on, the public has every right to ask whether this configuration reflects sound governance or institutional complacency. And David Graves, more than almost anyone else in this system, should have known better.

Part I: Two Decades as the Legal Gatekeeper

For more than twenty years, David Graves served as Sheffield Lake’s Law Director and Prosecutor. That position is not ceremonial, advisory, or marginal. Under Ohio law, the law director is the city’s chief legal officer, charged with representing the municipality in all legal matters, advising council and the mayor, preparing and approving contracts, and prosecuting violations of municipal ordinances. Ohio Revised Code 733.03 places the law director at the center of municipal governance, not as a passive reviewer but as an active legal authority whose interpretations and approvals shape how a city functions day to day.

In Sheffield Lake, that authority was compounded by duration. Two decades is not merely a long résumé line. It is enough time for a single attorney to outlast multiple mayors, multiple councils, shifting political coalitions, and changing administrative priorities. Over that span, the law director stops being just a legal advisor and becomes the institutional memory of the city. He knows why clauses were written a certain way, which compromises were struck quietly, which enforcement battles were fought and which were avoided, and where the legal pressure points actually lie when disputes arise.

Graves did not simply advise on isolated or routine matters. Sheffield Lake is not a self contained municipality. It relies on Lorain and neighboring jurisdictions for essential services, particularly water and sewer treatment, and it participates in a web of mutual aid and intergovernmental agreements that cross municipal boundaries. Every one of those relationships carries legal consequences. Every one of them requires statutory authority, contract drafting, liability allocation, indemnification language, termination provisions, and dispute resolution mechanisms. Those are not decisions made by engineers or administrators. They are legal decisions, and they pass through the law director’s office.

Even when the mayor signed and council voted, the law director’s role remained decisive. Municipal contracts in Ohio are not valid simply because they are politically approved. They must be legally sufficient. The phrase “approved as to form” is not decorative language. It is a declaration that the city’s chief legal officer has reviewed the agreement and accepts responsibility for its legality and enforceability. That approval is the choke point. Without it, the agreement does not move forward.

The sewer treatment agreement between the City of Lorain and the City of Sheffield Lake makes this reality concrete. It is not a short term service arrangement or a minor administrative contract. It is a long term infrastructure agreement that replaces prior contracts and binds Sheffield Lake’s most basic public health function to Lorain’s system for years into the future. The agreement contains an explicit approval line for the Sheffield Lake Law Director, affirming legal review and acceptance. That is where legal responsibility lives. It is where statutory authority, risk allocation, and enforcement pathways are locked in.

And that agreement did not exist in isolation. It exists within a lineage of earlier contracts, amendments, renewals, rate adjustments, compliance questions, and dispute communications. Over a twenty year tenure, the same law director is inevitably involved in those iterations. He fields the complaints. He drafts the response letters. He advises whether an issue is handled informally or escalated. He determines when something becomes an enforcement matter and when it remains an administrative disagreement. Those decisions rarely make headlines, but they shape how power is exercised between municipalities.

The same is true of mutual aid agreements for police and fire services, shared investigative authority, and cooperative enforcement arrangements. These agreements are authorized by statute, but their real world effect depends entirely on how they are written and interpreted. Over decades, a single law director becomes fluent in how these agreements operate in practice, not just on paper. He knows which provisions are enforced strictly and which are treated as flexible. He knows how disputes have historically been resolved and which arguments tend to succeed when matters reach court.

When you multiply one long term utility agreement by decades of amendments, renewals, disputes, side letters, and parallel agreements across multiple service areas, the footprint becomes impossible to ignore. This is not about one document or one decision. It is about cumulative legal influence. It is about how a city’s relationships with its neighbors are shaped over time by a single legal office and, in this case, by a single individual occupying that office for a generation.

That is why the phrase “legal gatekeeper” is not rhetorical flourish. It is an accurate description of the role Graves occupied. He was the gate through which Sheffield Lake’s most consequential intergovernmental relationships passed. Understanding that reality is essential before evaluating what it means for that same individual to now prepare to step into the judicial system that sits downstream from those very relationships.

Part II: One Lawyer, Multiple Cities

David Graves was never a one city lawyer, and that fact sits at the heart of this investigation. For the same decades that he served as Sheffield Lake’s Law Director and Prosecutor, Graves simultaneously held legal authority in other municipalities across the same geographic and judicial footprint. He served as Solicitor for Sheffield Village and as Assistant Law Director for Avon Lake, and in Avon Lake he periodically stepped into even broader authority as Acting Law Director and Acting Zoning Administrator. These were not symbolic titles. They were operational roles carrying real decision making power.

This matters because municipal law does not exist in isolation. Cities do not operate like independent silos with sealed legal borders. Sheffield Lake, Sheffield Village, Avon Lake, Lorain, and Sheffield Township exist inside a shared ecosystem of services, enforcement, infrastructure, and courts. They share borders. They share service dependencies. They share mutual aid arrangements. Most importantly, they share the same court of record. Lorain Municipal Court sits at the center of that system, adjudicating cases that arise from ordinances, contracts, enforcement actions, and disputes originating in these municipalities.

Sheffield Village sits within Sheffield Township, which, like Sheffield Lake, feeds criminal and ordinance cases into Lorain Municipal Court. Avon Lake borders Lorain directly and participates in regional cooperation agreements that inevitably intersect with Lorain’s infrastructure and enforcement systems. These cities rely on the same statutory frameworks, the same judicial interpretations, and often the same practical understandings of how disputes are handled when they reach court.

When one attorney occupies legal roles across that entire ecosystem for years, the effect is cumulative. He does not simply provide compartmentalized advice to disconnected clients. He becomes fluent in the entire regional legal landscape. He knows which cities historically defer and which push back. He knows which provisions are routinely enforced and which are treated as negotiable. He understands how certain clauses play out in practice once a matter reaches Lorain Municipal Court, because he has been there as an advocate and prosecutor. He learns, over time, how the system actually works, not just how it is supposed to work on paper.

That level of embedded knowledge is not inherently improper. In fact, it is often praised as experience. But experience becomes ethically fraught when it is carried across roles that are supposed to be structurally separate. The problem is not that Graves knows how these municipalities function. The problem is that the same person who accumulated that knowledge across multiple cities now proposes to step into the judicial system that resolves disputes arising from those very relationships, while retaining active legal roles inside that same municipal network.

At this point in a career, Graves cannot plausibly claim ignorance of how this looks or why it matters. A lawyer who has spent decades advising councils, navigating intergovernmental contracts, and appearing in Lorain Municipal Court understands the importance of boundaries. He understands that municipal clients are not abstract entities but political bodies whose interests often conflict quietly beneath the surface. He understands that courts derive legitimacy not only from impartial decision making but from the appearance of independence from the parties before them.

And yet, despite that knowledge, Graves publicly stated that he intends to retain his other municipal legal roles while preparing to take on a magistrate position in the same court system those municipalities rely on. That choice is not accidental. It reflects a normalization of overlap that has grown over time, where the same small circle of legal actors moves fluidly between city halls and courtrooms without meaningful structural separation.

When legal authority is concentrated this way, norms are shaped not by statute alone but by habit. Expectations harden. Informal understandings replace formal guardrails. And the public is left to trust that everyone involved can mentally compartmentalize roles that, by design, are supposed to be kept apart.

This is the danger of the multi city lawyer model when it is allowed to persist unchecked for decades. It creates a legal environment where boundaries blur slowly and almost invisibly, until one day the same individual stands poised to occupy a judicial role at the center of a system he helped wire together. At that point, the issue is no longer about competence or intent. It is about whether the structure itself has failed to protect the independence it claims to value.

Part III: The Court at the Center of Everything

Lorain Municipal Court is not a distant or abstract institution in this story. It is the gravitational center of the municipal ecosystem I have been documenting for years. It is the court of record for Sheffield Lake and Sheffield Township, and it routinely hears cases originating in Sheffield Village and Avon Lake as well. Criminal prosecutions, ordinance enforcement, traffic matters, housing matters, and disputes tied directly to municipal operations all funnel into this one courthouse. When municipal power is exercised in its most concrete form, when discretion hardens into enforcement, Lorain Municipal Court is where that power is made real.

For decades, David Graves operated inside this system from the municipal side. As Sheffield Lake’s prosecutor and law director, and as legal counsel for other municipalities, he appeared in Lorain Municipal Court as an advocate. He filed cases there, argued motions there, negotiated outcomes there, and relied on the institutional rhythms of that court to advance municipal interests. At the time, that was appropriate. He was doing the job he was hired to do.

But context matters, and the context has changed.

In late 2025, Graves was publicly announced as a future magistrate of Lorain Municipal Court. That announcement did not come with any indication that he would fully disengage from the municipal legal ecosystem he helped shape. In fact, Graves himself stated that while he would step away from Sheffield Lake, he intended to retain his other municipal legal roles.

That is where the structure begins to collapse inward.

A magistrate is not a background administrator. Magistrates preside over arraignments, conduct hearings, rule on motions, take testimony, assess credibility, and issue findings that judges frequently adopt wholesale. In practice, magistrates exercise delegated judicial authority that has immediate and lasting consequences for real people. They are often the first judicial officer a defendant, a resident, or a property owner encounters, and their discretion shapes the trajectory of cases long before a judge ever reviews the file.

Layered on top of this is another fact that cannot be ignored. Sheffield Lake Mayor Rocky Radeff works inside this same court system as a prosecutor. This is not an incidental overlap. Graves worked directly for Radeff in Sheffield Lake while Radeff served as mayor. Their professional relationship is recent, documented, and rooted in shared governance and shared legal decision making.

From my perspective, this matters enormously.

It tightens the loop between municipal executive authority and the court in a way that should give anyone who values judicial independence pause. The mayor of Sheffield Lake, who exercises executive authority over the city and who was directly involved in some of the most contentious legal disputes Sheffield Lake has faced, prosecutes cases in the same court where his former law director is now poised to serve as a magistrate. This is not conjecture. It is a matter of record.

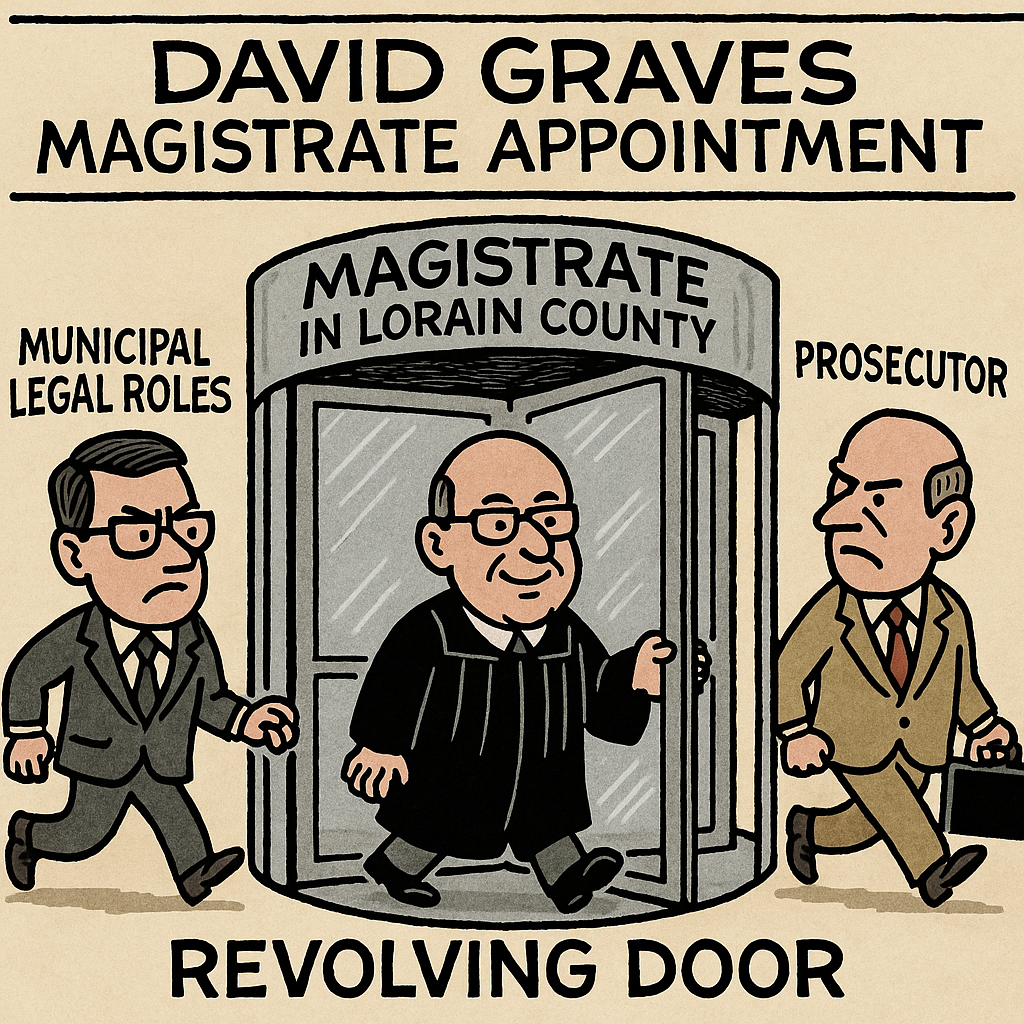

This is what the revolving door looks like at the local level.

It is not a dramatic leap from public office to private profit. It is quieter, more normalized, and far harder to challenge. Lawyers move between city hall, prosecutor roles, advisory positions, and judicial appointments within the same small geographic and institutional footprint. Each move is legal. Each move can be defended in isolation. Taken together, they form a closed circuit of influence that the public is rarely invited to examine.

From where I sit, the concern is not about secret collusion or personal misconduct. That is not how systems usually fail. The concern is familiarity. It is proximity. It is the slow erosion of distance between those who enforce the law, those who advise enforcement, and those who adjudicate enforcement. When the same individuals have worked together across roles, defended each other’s decisions, and navigated political controversy side by side, the appearance of independence is already compromised, whether anyone intends it or not.

Courts do not derive legitimacy solely from reaching technically correct outcomes. They derive legitimacy from public confidence that decisions are made by actors who are structurally insulated from the interests before them. That insulation must be visible. It cannot be assumed.

When a future magistrate has spent decades representing municipalities that appear in the court, plans to continue representing some of them, and has worked directly for a sitting mayor who prosecutes cases in that same court, I am left with a question that cannot be brushed aside. Where does advocacy end and adjudication begin. Where are the walls. Who built them. And who, if anyone, is responsible for making sure they still stand.

This is the hybrid role problem at its clearest. It is not about one man’s character. It is about a system that has allowed overlap to become so normalized that its risks are no longer acknowledged. When normal itself becomes the problem, sunlight is not an attack. It is the only corrective tool the public has left.

Even If It Is “Only” Small Claims, the Structural Problem Does Not Go Away

If the magistrate position David Graves is slated to assume is framed as a small claims assignment, that does not cure the problem. It reframes it, but it does not neutralize it.

Small claims court is often described casually, almost dismissively, as low stakes or ministerial. That description is inaccurate. Small claims is where real people collide with government power in its most stripped-down form. It is where residents challenge fees, utility charges, assessments, contract breaches, property damage, towing disputes, and enforcement fallout. It is where municipalities appear frequently, sometimes directly, sometimes through agents, contractors, or assignees.

In other words, small claims is precisely where intergovernmental contracts and municipal operations surface as lived consequences.

From my perspective, that makes the overlap more concerning, not less.

Small Claims Magistrates Still Exercise Judicial Power

A small claims magistrate is still a judicial officer exercising delegated authority of the court. They hear evidence. They assess credibility. They rule on liability. They decide whether a resident owes money to a city, a contractor, or an entity acting on the city’s behalf. Their findings are routinely adopted by judges unless timely objections are filed, and most litigants in small claims never file objections because they lack counsel, time, or procedural knowledge.

Calling the role “small claims” does not reduce its power. It concentrates it.

A magistrate in that setting is often the only adjudicator a person ever encounters. There is no jury. There is limited discovery. There is limited motion practice. There is enormous discretion, exercised quickly, informally, and with little public visibility.

That is not a side room. That is a pressure valve for the system.

The Overlap Still Exists, Even If the Docket Is Narrower

Even if Graves were assigned exclusively to small claims, the structural overlap remains intact.

The same municipalities he has represented for decades, and in some cases still represents, appear in that court either directly or indirectly. Utility billing disputes, sewer charges, service fees, code enforcement fallout, contract claims involving municipal vendors, and collection actions tied to city operations all end up in small claims. These cases are not abstract. They arise directly from the very agreements, policies, and enforcement regimes Graves helped design or enforce as a municipal lawyer.

From my point of view, it does not matter whether the case caption reads “City of Sheffield Lake” or “XYZ Utility Services LLC.” The underlying authority still traces back to municipal decisions. The legal DNA is the same.

And that is before even addressing perception.

Judicial Ethics Is About Appearance, Not Just Scope

One of the most misunderstood aspects of judicial ethics is that it does not hinge on how big or small the docket is. It hinges on whether a reasonable observer would question the independence of the decision-maker.

If a resident appears in small claims court to challenge a sewer bill, a utility charge, or a municipal enforcement consequence, and the magistrate presiding over that case is the same lawyer who spent decades approving the contracts, interpreting the ordinances, or advising the city on enforcement strategy, the appearance problem is immediate.

It does not vanish because the dollar amount is lower.

In fact, the lower the stakes, the less likely a litigant is to object, appeal, or challenge the assignment. That makes transparency and structural insulation even more important, not less.

The Revolving Door Argument Does Not Shrink With the Title

From where I sit, describing the role as “small claims” risks becoming a semantic shield rather than a substantive answer. The revolving door concern is not about prestige. It is about movement between advocacy and adjudication inside the same system, involving the same actors, the same municipalities, and the same court.

Whether the robe is worn in traffic court, housing court, or small claims, the core issue remains the same. A lawyer who helped wire together a municipal ecosystem should not then step into a judicial role inside that ecosystem without clear, written, publicly disclosed safeguards.

Calling the position small claims does not dismantle the loop. It simply moves it into a quieter room.

Why This Actually Makes the Timing Question More Urgent

If the court intends to assign Graves to small claims, that decision should be disclosed openly, along with the recusal rules, assignment protocols, and limitations on municipal appearances before him. Silence is not neutral here. Silence allows assumptions to harden, and assumptions are corrosive in a court system.

From my perspective, the responsible question is not “Is it only small claims?”

The responsible question is “Why does the court believe scope alone resolves structural conflict?”

If that answer cannot be articulated clearly and publicly, then the problem is not the assignment. The problem is the system’s comfort with overlap.

Bottom Line

Even if the magistrate role is limited to small claims, the concerns I am raising do not evaporate. They become more subtle, more insulated from scrutiny, and more likely to affect ordinary residents without meaningful review.

This is not about accusing anyone of bias. It is about recognizing that judicial independence is not measured by docket size. It is measured by distance from the court’s interests.

And from where I sit, that distance has not been adequately explained.

Part IV: Why Timing Does Not Save This

One of the most predictable responses to concerns like these is the claim that it is simply too early, that because David Graves has not yet assumed magistrate duties, scrutiny is premature. From my point of view, that argument misunderstands both how judicial ethics work and how institutional failures actually occur.

The concern here is not retrospective misconduct. I am not alleging that Graves has acted improperly from the bench, because he has not yet sat on it. The concern is prospective design. It is about whether the system is being constructed in a way that makes conflicts foreseeable, normalized, and difficult to unwind once the transition is complete.

Judicial ethics is not reactive. It is preventative. Courts are not supposed to wait until something goes wrong and then patch the damage. They are supposed to anticipate where structural entanglements may arise and address them before authority is exercised. That is why appearance matters as much as intent. That is why public confidence is treated as a value in itself. And that is why safeguards must exist before the first case is assigned, not after the first complaint is filed.

Right now, those safeguards are conspicuously absent from public view.

As of late 2025, the public does not know whether Graves will resign his remaining municipal legal roles before taking the bench. The Chronicle-Telegram article announcing his appointment suggests he will not, as Graves himself stated he intended to continue serving other municipalities. That alone should have triggered an immediate and transparent discussion about boundaries. Instead, it has been treated as an administrative footnote.

The public also does not know whether Lorain Municipal Court has issued, or even contemplated issuing, an administrative order governing recusals, case assignments, or disclosure requirements related to Graves’s prior and ongoing municipal work. No such order has been published. No guidance has been released. No explanation has been offered for how cases involving Sheffield Lake, Sheffield Village, Avon Lake, or related entities will be handled once Graves assumes judicial duties.

From where I sit, that silence is not neutral. Silence is a choice.

It suggests that the system is comfortable proceeding on the assumption that informal understandings will suffice, that everyone involved will simply “know” when to step aside, and that the public need not be informed of how those decisions are made. That assumption is precisely what erodes confidence over time. Informal guardrails are not guardrails at all. They are habits, and habits are invisible to the people most affected by them.

This matters even more because Graves is not entering the court as an outsider. He is a long-time municipal legal architect whose work continues to shape the very relationships that feed cases into Lorain Municipal Court. Utility agreements, enforcement mechanisms, and intergovernmental arrangements do not dissolve when a lawyer changes titles. They persist, and so does the knowledge of how they were constructed. Without formal, written, and public safeguards, that legacy follows him into the courtroom.

Timing does not insulate the system from scrutiny. Timing demands it.

If these questions are not asked now, before Graves takes the bench, they become exponentially harder to address later. Once cases are assigned, once decisions are made, once litigants are affected, any attempt to raise structural concerns will be dismissed as sour grapes or personal grievance. Preventive oversight will be reframed as reactive criticism, and the opportunity for clean correction will have been lost.

From my perspective, the responsible course is obvious. Before the robe goes on, the court and the municipalities involved should explain, in plain terms, how conflicts will be avoided, how recusals will be handled, how assignments will be structured, and how the public will be informed. Absent that explanation, the system appears to be preparing to place a long-time municipal insider into a judicial role without addressing the predictable and avoidable entanglements that role entails.

That is not an attack on a person. It is a critique of a process that seems content to move forward without acknowledging its own risk.

Part V: Ohio Law Has Seen This Movie Before

Ohio ethics law does not require proof of corruption to sound an alarm. It does not wait for a scandal, an indictment, or a leaked recording. It operates on a much more sober premise. Public officials are expected to avoid situations where duties collide in ways that predictably undermine independence, distort judgment, or erode public confidence. The standard is not whether someone acted with bad intent. The standard is whether the structure itself invites divided loyalty.

This is not a novel concern. Ohio Attorney General opinions and Ohio Ethics Commission guidance have addressed variations of this problem for decades. Again and again, the warning is the same. When one person occupies roles that place them on both sides of a governmental relationship, the risk is not hypothetical. It is baked into the design. The public does not need to prove corruption to question legitimacy. The overlap alone is enough to warrant scrutiny.

The concern is not moral failure. It is functional failure.

When one role involves advocating for a municipality, defending its policies, enforcing its ordinances, or protecting its financial interests, and another role involves adjudicating matters that arise directly from those same actions, the conflict is structural. It exists regardless of how conscientious the individual may be. Firewalls, recusals, and informal understandings may reduce risk in theory, but they do not eliminate the appearance problem when the overlap is this deep, this regional, and this longstanding.

That reality becomes even more troubling when viewed alongside the role of Sheffield Lake Mayor Rocky Radeff.

Radeff does not exist on the periphery of this system. He occupies it from two directions at once. As Mayor of Sheffield Lake, he exercises executive authority over a city that relies on Lorain Municipal Court as its court of record. As a prosecutor in Lorain, he appears inside that very court, enforcing laws and advancing cases on behalf of the state and municipalities. This dual positioning has already raised questions in other contexts, particularly when Sheffield Lake legal controversies intersect with prosecutorial discretion and court proceedings in Lorain.

From my perspective, this is not an abstract ethics seminar. It is a live example of the same structural problem repeating itself.

Graves worked directly for Radeff in Sheffield Lake while Radeff served as mayor. Their professional relationship is recent, direct, and rooted in shared governance. Now, Graves is slated to step into a judicial role in the same court where Radeff prosecutes cases. The pattern is unmistakable. Municipal executive authority, municipal legal authority, prosecutorial authority, and judicial authority are all circulating through the same small group of actors within the same court system.

Ohio ethics law has warned about exactly this kind of convergence. Not because it assumes wrongdoing, but because it recognizes how power behaves when boundaries soften. When the same individuals rotate through advocacy, enforcement, and adjudication roles, even if technically compliant with individual statutes, the system begins to look less like a neutral arbiter and more like an insider network. Trust erodes not because of what is proven, but because of what appears normalized.

What makes this especially concerning is that none of this is happening accidentally. These are not obscure overlaps discovered after the fact. They are known relationships, publicly acknowledged roles, and conscious decisions. At this stage, both Graves and Radeff are seasoned public lawyers. They understand how ethics law works. They understand how appearance matters. They understand how courts derive legitimacy. Proceeding anyway is not ignorance. It is acceptance of a risk that the public never agreed to bear.

Ohio law has seen this movie before because local government repeats these patterns when convenience is allowed to outweigh caution. Each individual step can be defended. Each role can be justified. But when viewed as a whole, the structure begins to contradict the very principles the law is supposed to protect.

From where I sit, the question is no longer whether this arrangement is technically permissible. The question is whether it is defensible in a system that depends on public confidence to function. Ethics law exists precisely to force that question into the open, before the damage is done and long before anyone is forced to argue about intent.

And when the same names keep appearing on both sides of the courtroom door, the law has already given us the warning.

Part VI: Why the Utility Contracts Matter More Than the Headlines

I did not request the water and sewer agreements by accident, and I did not request them because they were obscure. I requested them because utility contracts are where municipal power actually lives, long after elections are over and press releases stop. These agreements are not background noise. They are the backbone of Sheffield Lake’s operational dependence on Lorain, and they are the same instruments that quietly tie local government to the court system when things go wrong.

Water, sewer, and infrastructure contracts are where cities are most tightly intertwined. They are long term. They are expensive. They are technical enough to avoid public scrutiny and consequential enough to generate constant friction. Billing disputes, rate increases, compliance enforcement, service interruptions, and emergency overrides do not usually produce front page scandals. They produce letters, motions, collection actions, and enforcement hearings. They surface slowly, and when they finally surface, they do so in court.

That is why Lorain Municipal Court matters here.

When a resident disputes a sewer charge, when a property owner challenges an assessment, when a contractor sues over a utility related obligation, or when a city enforces payment tied to these agreements, the dispute does not play out in council chambers. It plays out before a magistrate or judge. Quietly. Procedurally. Often without lawyers on one side of the table.

I originally sought these contracts to demonstrate how Sheffield Lake Mayor Rocky Radeff was structurally tied to Lorain through long term agreements while simultaneously operating inside Lorain as a prosecutor. The documents showed exactly what I expected. Sheffield Lake’s relationship with Lorain is not incidental. It is contractual, operational, and ongoing. The city does not merely cooperate with Lorain. It relies on Lorain for essential services governed by binding legal instruments.

Now the same pattern reappears with David Graves.

These agreements were not written in a vacuum. They were reviewed, approved, interpreted, and enforced by the Sheffield Lake Law Director. Over decades, that meant Graves. His approval “as to form” is not a courtesy signature. It is the legal gateway through which these obligations passed. It represents decisions about liability, remedies, termination, and enforcement that continue to matter today.

When the same individual who approved and enforced those agreements prepares to step into the court system that resolves disputes arising from them, the question is not whether he will act unfairly in a given case. That framing is too narrow and too forgiving. The real question is whether the system should ever allow that configuration to exist without explicit, written, and public safeguards.

This is where the comparison to Radeff matters.

In both cases, the issue is not personality. It is structure. Radeff’s dual presence as Sheffield Lake Mayor and Lorain prosecutor raised legitimate questions about divided loyalty and institutional overlap. Those questions were not resolved by assurances of good faith. They were resolved by examining contracts, authority, and jurisdiction. The same analytical lens applies here.

Utility contracts are the connective tissue between municipalities and the court. They generate disputes that are rarely dramatic but deeply consequential. They are enforced incrementally, often against individuals with limited resources and limited understanding of the system. They are exactly the kind of cases where judicial independence must be beyond question, because the power imbalance is already severe.

From my point of view, dismissing these agreements as technical distractions misses the heart of the issue. These documents explain why the revolving door matters. They explain why timing matters. And they explain why the overlap between municipal legal authority and judicial authority cannot be brushed aside as theoretical.

This is not about whether one person can be trusted. It is about whether the system itself has been designed to prevent conflicts before they occur. When the same names appear repeatedly on contracts, enforcement actions, and now judicial appointments, the documents stop being paperwork. They become evidence of how power actually moves.

That is why the utility contracts matter more than the headlines.

Part VII: This Is Bigger Than One Man

This is not a personal attack on David Graves. Framing it that way would miss the point and let the system off the hook. What I am describing is a governance pattern that Lorain County has allowed to take root, normalize, and replicate itself across multiple municipalities and institutions. Graves is not an outlier. He is a case study.

Small and mid sized counties often rely on a relatively small circle of attorneys to do an outsized amount of public work. Over time, those attorneys move fluidly between city halls, law director offices, special counsel appointments, prosecutor roles, and judicial pathways. Each transition can be justified on paper. Each role is technically lawful. Each appointment is defended as experience. But when those roles accumulate in the same hands and circulate among the same few names, something else happens. Power begins to loop.

That loop is not theoretical. It is visible.

The same lawyers who advise councils later defend the actions of those councils. The same lawyers who draft ordinances later prosecute their enforcement. The same lawyers who argue in court later sit in positions to influence or shape how that court operates. Over time, institutional memory concentrates. Informal understandings replace formal safeguards. And the public is left interacting not with an open system, but with a closed circuit that appears impenetrable from the outside.

David Graves is one example. Joseph LaVeck is another.

LaVeck’s trajectory mirrors the same pattern. Moving between municipal legal roles, advisory positions, and influence over enforcement decisions, LaVeck has been a recurring figure in Lorain’s most contentious governance disputes, particularly around public records, executive session practices, and council authority. Like Graves, LaVeck is often presented as a neutral technician simply “doing his job.” And like Graves, his presence across multiple points in the system has had real consequences for transparency and accountability.

This is how the problem perpetuates itself. It is not driven by conspiracy. It is driven by convenience. Officials rely on familiar counsel. Courts rely on experienced insiders. Lawyers rely on long standing relationships. Over time, those relationships harden into expectation. Challenging them is treated as disruption rather than oversight.

The result is a system that may function efficiently but does not function transparently. Efficiency becomes the defense. Experience becomes the justification. And anyone who questions the structure is told to trust the process without being allowed to see how that process is wired.

When controversy arises, whether over elections, public records denials, enforcement disparities, or accountability failures, the same pattern repeats. Decisions are made behind closed doors. Executive sessions are invoked. Legal opinions are cited without being released. The public is assured that everything is lawful, while being denied the information necessary to independently verify that claim.

From my perspective, that is the defining failure. Democracy does not collapse because laws are broken. It collapses because systems become so closed and self referential that accountability becomes performative. The revolving door keeps turning, not because anyone forces it to, but because no one ever stops it.

This is why focusing solely on David Graves misses the broader danger. If this were only about one lawyer, it would be easily fixed. The problem is that the same structure exists across Lorain County, replicated in different names, different offices, and different disputes. Graves is simply the most visible example at this moment because his transition makes the overlap impossible to ignore.

The question is not whether these individuals are competent. The question is whether a system that continually recycles the same legal actors across advocacy, enforcement, and adjudication roles can ever claim to be meaningfully independent. From where I sit, that is the question Lorain County has avoided for far too long.

And avoiding it does not make it go away.

Conclusion: Before the Robe Goes On

David Graves has not yet taken magistrate duties, and that fact is not incidental. It is the last meaningful opportunity to examine this structure honestly, before judicial authority is exercised and before institutional inertia makes accountability impossible. Once the robe goes on, once cases are assigned, once findings are issued, the nature of this conversation will inevitably be distorted. Questions that should have been routine will be recast as personal attacks. Structural critique will be dismissed as bias. Preventive oversight will be reframed as retaliation. That is how systems protect themselves after the fact. It is not how they protect the public.

This moment matters because David Graves does not approach the bench as a neutral outsider.

He approaches it carrying recent, concrete roles that go directly to the heart of judicial independence.

Graves was not merely a municipal advisor in Sheffield Lake. He was the city’s prosecutor, exercising discretionary power over residents whose cases flowed into Lorain Municipal Court. More importantly, he also served as Special Prosecutor in the Lorain Police Department Sergeant Rivera case, a role that placed him squarely inside Lorain’s law enforcement apparatus, acting on behalf of the state in a highly sensitive internal police matter.

That designation is not cosmetic. A special prosecutor is brought in precisely because neutrality is supposed to be heightened, not blurred. It is an acknowledgment that ordinary prosecutorial channels may be conflicted or politically entangled. When the same individual who served as special prosecutor in a Lorain police case is later positioned to assume a judicial role in the same court system, the public is entitled to ask whether the system has meaningfully separated advocacy from adjudication, or merely relabeled it.

This is not ancient history. It is recent. It places Graves in direct prosecutorial alignment with Lorain law enforcement, at the same time he was serving as law director and prosecutor for Sheffield Lake, and while Sheffield Lake’s mayor, Rocky Radeff, was operating inside Lorain Municipal Court as a prosecutor as well. These roles did not exist in isolation. They overlapped in time, in personnel, and in institutional interest.

Layer on top of that Graves’s recent conduct in Sheffield Lake itself. His role in advancing the post-election challenge against Councilmember-elect Aden Fogel was not a passive legal opinion buried in a memo. It was an active intervention that sought to prevent a duly elected official from taking office after certification. Had that effort succeeded, it would have removed from the council one of the members entitled to vote on Graves’s own replacement as law director. For a lawyer with more than two decades of municipal experience, that intersection of timing, power, and consequence cannot be waved away as inadvertent.

Taken together, these facts do not describe an isolated career move. They describe a pattern.

- A lawyer who has recently exercised prosecutorial authority on behalf of Lorain law enforcement.

- A lawyer who has recently acted to reshape the composition of a municipal legislative body.

- A lawyer who has spent decades drafting, approving, and enforcing intergovernmental agreements that feed disputes into Lorain Municipal Court.

- A lawyer who has publicly stated he intends to retain municipal legal roles while preparing to step into a judicial position in that same court.

That is not distance. That is proximity.

From my perspective, this is precisely the moment Ohio’s ethical framework is supposed to operate, not after damage is done. The law does not ask the public to prove bad faith. It asks officials to avoid structures that make divided loyalty predictable and confidence fragile.

So the questions must be asked now, clearly and publicly.

Will David Graves fully sever all municipal and prosecutorial roles before assuming magistrate duties.

If not, how does the court justify that overlap in light of his recent role as Special Prosecutor in a Lorain police case.

What formal, written recusal rules will govern his assignments, and who enforces them.

How will magistrate assignments be made, and will those decisions be transparent or merely internal.

Will litigants be informed, on the record, of his prior prosecutorial involvement in Lorain PD matters and his recent interventions in Sheffield Lake governance.

And has Lorain Municipal Court sought ethics guidance in advance, or is it waiting for controversy to force action.

These are not hostile questions. They are the minimum questions required to preserve legitimacy in a system that already operates under intense public skepticism. A court that cannot explain how it prevents foreseeable conflicts before they arise is not neutral by default. It is simply insulated.

What concerns me most is not the fear that David Graves might act improperly from the bench. It is the assumption that his experience entitles the system to skip the safeguards altogether. Experience does not replace independence. Familiarity does not substitute for distance. And silence does not create trust.

Sunlight is not an accusation. It is a safeguard. It is how institutions demonstrate that they deserve the authority they wield.

If this system is sound, it should withstand scrutiny now, before the robe goes on, while boundaries can still be drawn clearly and confidence can still be preserved. If it waits until after the revolving door has already turned, then whatever trust remains will have been traded away for convenience.

Before the robe goes on, the public deserves answers.

Writer Bio

Aaron Christopher Knapp is an investigative journalist, licensed social worker, and public records litigator based in Lorain County, Ohio. He is the founder and editor in chief of Lorain Politics Unplugged, an independent accountability journalism project focused on municipal governance, public records compliance, and civil rights oversight. Knapp’s work centers on document driven reporting, statutory analysis, and first person accountability journalism grounded in verifiable public records. He has prevailed in multiple Ohio Court of Claims public records actions and routinely analyzes the intersection of local government power, prosecutorial discretion, and judicial ethics. His reporting philosophy is simple and non negotiable. Government belongs to the people, and sunlight is not optional.

Legal Disclaimer

This article is published for informational and journalistic purposes only. It is based on publicly available records, official statements, court filings, government contracts, meeting minutes, and contemporaneous reporting. All statements of fact are supported by source material believed to be accurate at the time of publication. Any analysis, interpretation, or opinion expressed herein constitutes protected speech under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution. Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal advice, an allegation of criminal conduct, or a statement of guilt. Readers are encouraged to review the underlying public records and draw their own conclusions.

AI Assistance Disclosure

This article was drafted with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools used for structural organization, language refinement, and synthesis of publicly sourced information. All factual assertions, legal citations, and narrative conclusions were reviewed, edited, and approved by the author. The author retains full editorial control and responsibility for the content. AI tools were not used to generate facts, fabricate sources, or replace independent judgment.

AI Image Disclaimer

Any images or illustrations accompanying this article that were generated or modified using artificial intelligence are illustrative only. They are not intended to depict real events, specific moments in time, or exact likenesses unless explicitly stated. AI generated visuals are used for editorial presentation and commentary purposes and should not be interpreted as photographic evidence.

Source Credit

This investigation was prompted in part by reporting from The Chronicle-Telegram, which first reported David Graves’s announced resignation from his role as Sheffield Lake Law Director and his planned transition to a magistrate position with Lorain Municipal Court. Credit is given to The Chronicle-Telegram for the original reporting that brought this development to public attention. Subsequent analysis, contextualization, and interpretation are the independent work of the author and based on public records, official documents, and historical municipal relationships.

SOME QUESTIONS FOR THOSE ASPIRANTS OF JUDICIAL AUTHORITY:

When did Detective Thomas Cantù’s investigative knowledge and report on the bus route of Nancy Smith first be disclosed to defense attorney Jack Bradley?

What is Special Prosecutor GRAVE’S stand on Brady violations?

Should a prosecutor who withholds exculpatory evidence be rebuked? How?

Is it a crime to convict an innocent man/woman?

Should a Court be run as a moneymaking enterprise?

If not, why not?

Do citizens who appear before a municipal court magistrate or Judge deserve to receive Constitutional Due Process? If so, what does that mean?

What are conflicts of interest? Why are they important to avoid?

What can a citizen post on his/her Facebook or U-Tube page and not be sentenced for direct contempt in the Lorain Municipal Court?

What other questions should be asked?