Investigating Conflicts and Misconduct in a Lorain County Custody Case

Aaron Christopher Knapp, BSSW, LSW

Investigative Journalist, Government Accountability Reporter

Editor-in-Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker (LSW)

Public Records Litigant & Research Analyst

AaronKnappUnplugged.com

A Court in Question: When Custody Disputes Reveal Systemic Failures in Lorain County

In the evolving custody matter that has brought troubling allegations to light, Lorain County Domestic Relations Court has once again become a focal point for accusations of procedural irregularities, ethical breaches, and systemic bias. Central to this unfolding controversy are figures whose roles are supposed to guarantee neutrality and the best interest of the child, Judge Sherry L. Glass and Guardian ad Litem Andrea F. Limberty-Davis foremost among them. But the conduct attributed to both raises critical concerns about whether this custody proceeding has adhered to even the most fundamental requirements of due process under Ohio law, or if personal entanglements and unchecked discretion have irreparably tainted the court’s integrity.

My involvement in this story did not begin with a cold tip or distant observation. I was drawn into it when Guardian ad Litem Andrea Davis’s pattern of inappropriate conduct, already documented through prior investigative reporting, resurfaced in a new and disturbing context. A third party, familiar with Davis’s behavior and seeking to connect the mother involved in this current case with an advocate, reached out to me directly. That conversation resulted in the mother contacting me personally, not because she was seeking publicity, but because she feared that the mechanisms intended to protect her rights and her child’s safety had been hijacked by self-interest and systemic complacency. (https://bustednewspaper.com/ohio/limberty-davis-andrea-f/20191213-234400/#google_vignette)

This is not an isolated tale of judicial overreach. The Lorain County Domestic Relations Court has long operated in a fashion that breeds opacity, fosters retaliation against vocal litigants, and insulates certain officers of the court from meaningful accountability. What began as a private custody dispute has unraveled into a public reckoning with how far off course a legal system can drift when no one is watching, or worse, when those watching are too intimidated or politically entangled to intervene.

The legal principles that ought to govern custody proceedings are clear: neutrality, transparency, and the paramountcy of the child’s best interest. Those principles are enshrined in both the Ohio Revised Code and the Rules of Superintendence for the Courts of Ohio, including Sup.R. 48, which lays out the duties, qualifications, and removal criteria for guardians’ ad litem. Yet the facts emerging from this case suggest those mandates were not merely neglected but outright subverted. If substantiated, these allegations warrant far more than public outrage, they demand formal review, judicial inquiry, and, potentially, a remedy retroactive to every decision rendered under the shadow of bias.

This report is only the beginning of a broader examination into how custody courts in Lorain County operate when no one is keeping the gate. And as this case unfolds, it is not only the rights of one mother that hang in the balance, it is the public’s confidence in whether local family courts serve the law, or themselves.

Judge Sherry L. Glass: Recusal After Rulings

Judge Sherry L. Glass, elected to Lorain County Domestic Relations Court in 2016, occupied the bench throughout the most pivotal phases of the custody litigation in question. Her role encompassed issuing orders that shaped the structure of parental rights, mandated supervised visitation, and influenced how factual narratives were accepted into the record. Despite the magnitude of these rulings, Judge Glass did not recuse herself until much later, after several binding decisions had already taken effect. The basis for her eventual recusal remains shrouded in ambiguity. No formal explanation of the disqualifying conflict was made available in open court or the case docket, a silence that has only intensified public and legal scrutiny.

This is not a procedural footnote. Under Rule 2.11(A) of the Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct, any judge is required to step aside from a case when “the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” The standard does not require proof of actual bias, only a reasonable concern that the judge’s neutrality is in doubt. When recusal is delayed until after significant judicial acts, litigants may have already suffered the irreparable consequences of biased adjudication. These rulings, while technically valid unless vacated, are tainted by the cloud of impropriety, a result the rule is specifically designed to prevent.

Ohio law acknowledges this problem through statutory and procedural remedies. R.C. 2701.03 provides litigants with a mechanism to challenge judicial conduct on grounds of bias, and Ohio Civ.R. 60(B) allows for relief from judgment when fairness demands it. The mother in this case has invoked both. Her motion to vacate Judge Glass’s earlier orders contends that the rulings were the product of a compromised bench, and that continuing to enforce them constitutes an ongoing violation of her due process rights. The motion raises pointed legal questions: If a judge issues orders under a conflict and then recuses without disclosing the nature of that conflict, can those orders truly stand?

The issue is neither speculative nor unprecedented. In Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., 556 U.S. 868 (2009), the United States Supreme Court held that the failure of a judge to recuse herself in the face of a substantial risk of actual bias violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court emphasized that even the appearance of bias can be enough to undermine judicial legitimacy, particularly when one party is exposed to systemic disadvantage. In Caperton, the bias stemmed from campaign contributions; in the current case, the origin of the conflict remains obscured, but the principle is the same. Justice must not only be done, it must be seen to be done.

The implications extend beyond the immediate parties. If a judge withholds a conflict until after issuing impactful decisions, and the legal system permits those rulings to remain untouched, the safeguard of judicial recusal becomes an empty formality. For litigants, especially in family court where outcomes affect parental bonds, the damage is deeply personal and often irreversible. For the legal community and the public, it signals a breakdown in accountability at one of the judiciary’s most vulnerable points. The mother’s invocation of Caperton is not merely rhetorical; it places the conduct of Judge Glass within a national framework of constitutional expectations and reinforces that state procedure cannot be permitted to erode federal due process guarantees.

A Court that Doesn’t Know it’s Own Rules: My Experience as a Pro Se Litigant

Several years before the custody matter now drawing public scrutiny began unraveling under the weight of judicial and ethical failures, I appeared as a pro se litigant in the same courthouse now under examination. I was attempting to enforce a valid out-of-state child custody order in Lorain County Domestic Relations Court, an action governed by the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act, which Ohio has adopted through R.C. 3127.01 and the sections that follow. The procedure, according to statute, should have been straightforward and ministerial in nature. Yet it quickly turned into a procedural impasse that revealed not only institutional incompetence but also the hostility sometimes directed at unrepresented litigants.

When I attempted to register the foreign custody order, clerical staff balked. Rather than process the paperwork as required by law, they expressed confusion and attempted to impose filing fees that were not authorized in such proceedings. Under Ohio law, specifically R.C. 3127.35 and R.C. 3127.36, courts have an affirmative duty to register out-of-state custody determinations and schedule a hearing upon proper request. This is not optional. These statutes are clear, mandatory, and crafted to ensure uniform enforcement of custody orders across jurisdictions. The staff, however, acted as though the statutory framework did not exist.

At no point was I treated as someone invoking a well-established area of domestic relations law. Instead, I was treated as a nuisance. I was forced to cite chapter and verse to court personnel whose job it was to understand those provisions. After I objected and provided the relevant statutory authority, the matter was escalated to a court attorney before it ever reached Judge Glass for review. That attorney, to their credit, reviewed the situation, acknowledged the staff’s error, and later Judge Glass refunded the unlawful fee that had been collected. While the refund itself corrected one small part of the problem, it did not address the larger issue. The court had failed to carry out a routine legal procedure.

The error only came to light because I was prepared to advocate for myself using black-letter law.

Aaron Knapp

The Ohio Supreme Court has been clear on the role of court clerks. They are not gatekeepers with discretionary power to question the validity of filings that comply with procedural rules. They are ministerial officers charged with accepting documents that meet the filing criteria. Their role is to facilitate access to the courts, not obstruct it. Yet in my experience, the clerical staff at Lorain County Domestic Relations Court behaved as though the law was an inconvenience, not a mandate.

This is not an isolated anecdote. It is a symptom of a broader culture that undermines the rights of individuals who come before the court without legal representation. When even basic procedural duties are treated as optional, and when correction only occurs after confrontation, the system ceases to function as a neutral arbiter of the law. It becomes something else entirely. And for those of us who rely on it to protect our rights, failure is not academic. It is personal and enduring.

Andrea Limberty-Davis: A Pattern of Misconduct Ignored by the System

When Judge Sherry L. Glass appointed Andrea F. Limberty-Davis to serve as Guardian ad Litem in 2020, the decision was made against the backdrop of Davis’s recent arrest, which occurred just months earlier on December 13, 2019. According to publicly available records, that arrest stemmed from an incident classified as domestic violence, a matter that, regardless of its legal resolution, ought to have triggered heightened scrutiny given the nature of the GAL role. A Guardian ad Litem is tasked with serving the best interests of the child, a function that requires unimpeachable personal conduct and the ability to remain neutral in the midst of high-conflict litigation. The Supreme Court of Ohio’s Rules of Superintendence, specifically Rule 48.03(A)(2), mandate that all GALs must remain objective, fair, and free of personal entanglements that could compromise their service. The appointment of Davis in light of her recent arrest raises obvious and unsettling questions. Either the court and the CASA oversight program failed to conduct a background review adequate enough to uncover the arrest, or they found it and decided it did not matter.

This appointment does not merely reflect on Davis. It implicates the entire vetting structure, particularly Voices for Children, the Lorain County CASA program headed by Director Tim Green. CASA, or Court Appointed Special Advocates, is intended to function as a check on the very system it serves, providing oversight and qualified recommendations to the bench. But if CASA leadership was either unaware of or indifferent to a pending criminal matter against one of their advocates, it demonstrates an operational breakdown. The public should not have to guess whether their child’s GAL was arrested weeks before appointment. Such failures undermine faith in the program, and worse, they create risks for the very families the system claims to protect.

Yet the problems with Davis’s conduct extended far beyond her personal legal history. During the course of the current custody dispute, Davis’s actions escalated into what can only be described as retaliatory surveillance. After the mother, who has since become a central whistleblower, posted publicly on social media inviting others to come forward about Davis’s prior conduct, Davis allegedly directed third parties to monitor, capture, and compile screenshots of the mother’s personal posts. These images, which the mother intended as a lawful expression of concern and a rallying cry for community feedback, were then submitted by Davis in court filings as purported evidence of the mother’s hostility. The strategy was both alarming and telling. Instead of remaining focused on the child’s welfare, Davis appeared preoccupied with salvaging her own professional image. The idea that a GAL would use third-party surveillance to gather material from a parent’s social media page, and then repackage that material as justification for adverse legal action, presents a profound ethical breach.

In her August 2025 motion to withdraw, Davis did not attempt to conceal the motivation behind her withdrawal. She explicitly cited the mother’s public posts as the reason for her inability to remain objective. This is not a neutral recusal. It is a concession that she allowed the parent’s constitutionally protected speech to influence her judgment. Rule 48.03(B)(2) of the Ohio Rules of Superintendence obligates GALs to disclose any conflict that may impede their ability to serve. In invoking the mother’s online speech as a basis for withdrawal, Davis did more than admit to a conflict. She demonstrated that she had already crossed the line between advocate and adversary. That her withdrawal motion framed the mother’s speech as “sanctionable conduct” only compounded the impropriety. Protected First Amendment expression, particularly when aimed at public officials or court appointees, does not qualify as misconduct. It is the precise type of speech our legal system is designed to protect.

That no disciplinary action appears to have been taken in response to this misconduct is perhaps the most damning evidence of all. CASA, the bench, and court administration allowed Davis to remain in place long enough to file withdrawal documents that effectively blamed the parent for exercising her rights. They did not intervene earlier. They did not investigate. They did not apologize. This abdication of responsibility raises urgent concerns about how Guardians ad Litem are monitored, and whether meaningful mechanisms exist to remove them when they violate ethical boundaries. If Davis’s arrest record was ignored, and if her retaliatory conduct was met with silence, then the Lorain County Domestic Relations Court cannot credibly claim to safeguard the interests of children and families. It has protected the system instead of the people.

Meanwhile, Judge Glass’s conduct also merits investigation. If her conflict was known to her early in the case and she nevertheless continued to preside, it is a violation of Canon 2 and Rule 2.11 of the Ohio Code of Judicial Conduct. Parties can file complaints with the Ohio Disciplinary Counsel if a judge fails to recuse in a timely and ethical manner.

Legal Sidebar: When a Guardian Becomes a Combatant — Andrea Limberty-Davis and the Collapse of Neutrality

Guardians ad Litem (GALs) are not advocates for either party. They are officers of the court whose duty is to represent the best interests of the child. Their mandate is governed by Rule 48 of the Ohio Rules of Superintendence, which requires neutrality, objectivity, and a posture of non-adversarial engagement. Andrea Limberty-Davis’s conduct in this case, however, illustrates what happens when that mandate collapses under the weight of personal grievance, retaliatory behavior, and what appears to be a systemic misunderstanding of the GAL’s function.

According to court filings and corroborating communication records, Davis escalated a disagreement with the mother into what can only be described as a campaign of reputational and procedural aggression. Rather than remaining a neutral voice for the child’s best interest, Davis monitored the mother’s social media activity, dispatched third parties to capture screenshots, and incorporated these materials into court filings in an apparent attempt to paint the mother as emotionally unstable and vindictive. These actions did not emerge from a child’s report or a substantiated threat to the child’s welfare. Instead, they appear to have been triggered by the mother’s decision to publicly express dissatisfaction with the GAL process and to encourage others who had negative experiences with Davis to come forward.

Protected speech under the First Amendment includes the right to criticize public officials and court actors, including GALs. While the courtroom may impose some limits on disruptive behavior within proceedings, extrajudicial commentary—particularly when it involves core political speech about systemic abuse, is a constitutionally safeguarded activity. Davis’s characterization of the mother’s comments as “sanctionable conduct,” as seen in her August 2025 Motion to Withdraw, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of these protections and an inappropriate conflation of personal embarrassment with professional misconduct. Her use of the court’s authority to silence or punish that speech borders on retaliatory abuse of process.

The pattern does not end with Facebook screenshots. As confirmed by multiple emails and private communications, Davis made efforts to contact this journalist through intermediaries, requesting that her 2019 mugshot, obtained after a domestic violence-related arrest, be removed from a previously published story. That arrest is a matter of public record. Although Davis has claimed the record was “expunged,” public access databases still contain references to the incident, and there is no indication that a judicial sealing order was issued or properly indexed. The timing of her request coincided with this new reporting effort, raising questions about whether the expungement claim was advanced to sanitize her public image ahead of renewed scrutiny.

Further, emails sent by Davis to the mother and counsel involved in the case are marked by an unmistakable tone of hostility. These are not the dispassionate reports expected of a GAL. Instead, they read as adversarial memoranda, littered with personal judgment and veiled threats. The court is not supposed to be a venue for score-settling. A GAL who views one parent as a personal adversary compromises the core function of the role and infects the process with bias. Under Sup.R. 48.03(B)(2), any GAL who believes they can no longer serve impartially is obligated to inform the court immediately. Davis did eventually move to withdraw, but only after months of caustic exchanges and procedural entanglements that left lasting damage to the parent-child relationship she was tasked with protecting.

There is also the matter of GAL compensation. While guardians are entitled to court-approved fees, questions have emerged about whether Davis used court orders to garnish funds in a way that exceeded ethical or legal boundaries. In multiple instances, fee enforcement actions appeared to lack adequate hearing or due process safeguards. Fee enforcement must follow R.C. 3109.04 and comply with due process under Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976), yet in this matter, fee recovery efforts bore more resemblance to collections litigation than child advocacy.

These cumulative behaviors suggest not a lapse in judgment, but a pattern—one that is incompatible with the ethical expectations of a GAL, and dangerous to the integrity of family court proceedings. If the function of the GAL becomes indistinguishable from that of a prosecuting party, the system has failed its most basic charge: to ensure that decisions about children are made without fear, favor, or reprisal.

Legal Sidebar: Neutrality Undermined and Ethical Rules Ignored

Andrea Limberty Davis’s conduct in this matter does not fall within the realm of subjective overreaction or misplaced intensity. It implicates specific statutory violations and breaches of binding ethical obligations that govern the role of any Guardian ad Litem in Ohio. Her actions are not isolated or accidental. They reflect a deliberate and escalating strategy of retaliation against a parent who criticized her conduct and exposed what many would argue is a disturbing pattern of behavior.

According to Sup.R. 48.03(A)(2), a Guardian ad Litem must maintain objectivity and independence at all times. The rule explicitly prohibits behaviors that would align the GAL with any party or suggest personal hostility. Davis’s response to the mother’s constitutionally protected speech included recruiting third parties to monitor private social media activity, harvesting screenshots, and submitting those materials in court filings designed to discredit the mother. These were not neutral disclosures made in the child’s best interest. They were argumentative filings that mirrored the tactics of adversarial counsel and reflected a retaliatory posture that no GAL is permitted to assume.

Under Sup.R. 48.03(B)(2), a GAL is required to notify the court immediately upon discovering a conflict of interest that compromises their ability to remain impartial. Davis did not disclose such a conflict early. Instead, she participated in the case with increasing aggression, then filed a motion to withdraw only after building a sanctions argument against the mother. The motion itself weaponized that conflict. She claimed her objectivity was compromised by the mother’s criticism but did so only after attempting to leverage that criticism to punish the mother. This is not a disclosure in service of impartiality. It is procedural opportunism masked as ethics.

Her behavior also falls under scrutiny when measured against the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct. Rule 8.4(c) bars conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation. Rule 8.4(d) bars any conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice. Filing court documents that characterize First Amendment speech as “sanctionable” and treating protected criticism as misconduct threatens to chill the rights of litigants and weaponizes the role of the GAL against the very families they are appointed to serve. This crosses into the terrain of misrepresentation and clearly prejudices the integrity of the court’s process.

Any request for sanctions under Civ.R. 11 or R.C. 2323.51 must be narrowly evaluated. Ohio courts stress that sanctions are reserved for filings that lack a good-faith basis in law or fact. For example, in State ex rel. Kostoff v. Beck Energy Corp., 2019-Ohio-1221, the Ninth District Court of Appeals reversed a trial court’s imposition of sanctions where it concluded that the attorney did have “good grounds” to support a temporary restraining order. Courts require a showing that the filing was frivolous and not supported by existing law or a good-faith argument for its extension. There is no Supreme Court case titled State ex rel. Thomas v. Franklin County Court of Common Pleas that addresses Civ.R. 11, and any prior reliance on that nonexistent case must be corrected.

Separately, attempts to erase public records raise further concern. Davis or her associates contacted this journalist requesting the removal of her 2019 mugshot and arrest history, citing an expungement. While Ohio Revised Code § 2953.32 permits sealing of criminal records under qualifying conditions, it does not authorize retroactive censorship of pre-existing public reporting. Nor does it prohibit the press from maintaining or publishing accurate information that was lawfully obtained and published at the time. Such contact, when undertaken to shield a public official or officer of the court from accountability, touches the perimeter of First Amendment interference and further compounds the appearance of retaliatory motive.

Taken in totality, the pattern of behavior here reflects more than a lapse in discretion. It reveals a method of operation that substitutes ego for ethics and retaliation for neutrality. When a GAL is permitted to surveil litigants, manipulate the record, solicit sanctions, and then exit the case with her grievances intact and her record unexamined, the entire system is compromised. What is at stake is not just the fairness of one case. It is whether a family court system governed by enforceable standards can prevent its officers from transforming child-centered proceedings into personal crusades. Unless these behaviors are subjected to public scrutiny and judicial discipline, they will become the norm rather than the exception.

A Disrupted Appointment: My Experience as a Guardian ad Litem

The dysfunction that now defines the Lorain County Domestic Relations Court was not something I discovered solely through investigation. I experienced it firsthand, not merely as a litigant but as an appointed Guardian ad Litem tasked with representing the interests of vulnerable children. My appointment, secured through required training and formal approval consistent with Sup.R. 48, should have provided a stable foundation for my work. Instead, I found myself the target of institutional sabotage. My status was abruptly questioned based not on any misconduct, ethical lapse, or professional deficiency, but because of an internal conversation between Tim Green, Director of the CASA program, and a court administrator who took it upon themselves to recharacterize my role.

Their rationale was that my “volunteer” designation disqualified me from performing duties that, according to the court’s own website and standards, are regularly carried out by trained volunteers under CASA. The implication was that I had somehow misrepresented my standing, even though CASA protocol explicitly identifies trained and appointed volunteers as officers of the court when acting in their GAL capacity. This mischaracterization appeared less like a good-faith misunderstanding and more like a calculated effort to remove someone unwilling to operate as a rubber stamp for institutional decisions. The result was an unofficial dismissal and the removal of my authority mid-case, carried out not through any formal hearing, investigation, or review of my performance, but through a series of undocumented conversations behind closed doors.

Though I was eventually reinstated after confronting the procedural errors and unlawful disruption of my appointment, the harm had already calcified. Cases proceeded in my absence, leaving children and families without the benefit of my advocacy. More damaging still was the shadow cast over my reputation, a stain not produced by public complaint or judicial reprimand, but by a quiet, internal smear campaign carried out by courthouse actors who faced no accountability. No hearing was ever held, no findings were issued, and yet the damage functioned as though there had been a formal censure. In this way, my experience echoes the broader themes evident in Andrea Limberty-Davis’s misconduct. Power in the Lorain County courthouse is often wielded through informal channels, enforced by a bureaucratic culture that discourages dissent, and rarely subjected to outside scrutiny.

This environment breeds retaliation against those who refuse to conform or who challenge procedural shortcuts. It was not the law that suspended my role as a GAL; it was the unchecked discretion of administrators who mistook their influence for legal authority. That type of structural informality, where roles are revoked without notice and reputations damaged through undocumented communications, is not just a flaw. It is a systemic feature that corrodes the very function of justice, particularly in cases where neutrality, transparency, and due process should be the court’s guiding principles.

Retaliation, Surveillance, and Withdrawal: The Pattern in Davis’s Conduct

The conduct of Andrea Limberty Davis in this custody case represents more than a professional misstep. It reveals a sustained pattern of escalation against one party, culminating in actions that appear retaliatory, procedurally aggressive, and ethically unsound. At the center of that pattern is a series of decisions and behaviors that, when viewed together, call into question whether Davis ever approached her role as Guardian ad Litem with the neutrality required by Ohio law.

The mother’s protected speech was the catalyst. Following a social media post where she shared her frustrations with the process and encouraged others who had experience with Davis to come forward, the GAL did not respond with reflection, transparency, or even quiet withdrawal. Instead, Davis enlisted third parties to monitor the mother’s Facebook activity and collect screenshots. Those images were subsequently submitted in court filings, not because they bore on the best interests of the child, but because they were critical of Davis herself. The act of turning a parent’s expression of concern into “evidence” against her marked a dangerous inversion of roles: the GAL ceased to be a neutral advocate and became an adversary.

In her August 2025 Motion to Withdraw, Davis described the mother’s public speech as “sanctionable conduct,” a characterization that is not only legally baseless but ethically alarming. The idea that a party to litigation cannot criticize a court appointee without risking reprisal cuts against the core of due process. That motion was followed by yet another, seeking the imposition of additional sanctions. Davis alleged that the mother’s demeanor and external communications, including contact with this journalist, warranted further restraints or penalties. These filings were made not in response to some procedural sabotage or factual misrepresentation by the mother, but in response to discomfort caused by transparency.

At the same time, Davis or those affiliated with her reached out to this journalist in an effort to scrub earlier reporting from public view. Specifically, they requested the removal of Davis’s 2019 mugshot and arrest information, claiming the case had been expunged. Whether or not the expungement holds, the timing of that outreach—coinciding with the mother’s broader public criticism, suggests that Davis was more concerned with optics than accountability. Records confirm that she was arrested on December 13, 2019, in a domestic violence matter. That arrest occurred just months before she was appointed by Judge Glass in this very case. Under any ordinary standard of vetting, that alone should have warranted pause.

Finally, Davis’s communications with the court and parties were persistently adversarial in tone. Her emails, included in the record, read more like filings from opposing counsel than updates from a neutral third party. She references unpaid GAL fees and frames them as part of the justification for her withdrawal, suggesting financial grievance was interwoven with her growing hostility. What should have been a withdrawal based on professional conflict instead became an opportunity to argue for further punishment of a parent whose primary offense appears to have been speaking out.

Remedies and Broader Implications

The mother’s pending motion under Ohio Civil Rule 60(B) seeks to unwind a series of court orders that she argues were issued under a cloud of compromised authority. Her argument is twofold. First, she asserts that the presiding judge, having failed to recuse herself in a timely manner despite a disqualifying conflict, deprived the proceedings of the impartial adjudication required under both state and federal due process standards. Second, she argues that the Guardian ad Litem, having admitted personal animus and demonstrated retaliatory conduct toward the mother, failed to meet the neutrality and fidelity to the child’s best interests required under Sup.R. 48.03. Together, these circumstances, she contends, rise to the level of structural error sufficient to void or vacate the resulting orders.

There is legal support for this position. In Patton v. Diemer, 35 Ohio St.3d 68 (1988), the Ohio Supreme Court held that a judgment rendered by a court lacking subject matter jurisdiction is void ab initio and may be collaterally attacked at any time. While subject matter jurisdiction is not directly at issue in this case, the Patton holding reinforces the principle that orders entered without legal authority—whether due to judicial disqualification or GAL misconduct—are not entitled to deference or finality. Similarly, in State ex rel. Stern v. Mascio, 81 Ohio St.3d 297 (1998), the Court reaffirmed that judicial disqualification implicates due process concerns, particularly when the judge in question has exercised decision-making power despite a conflict of interest. When such a conflict is identified, and when its impact is not merely procedural but substantive, the law permits those affected to seek relief from the resulting rulings.

These issues extend well beyond the facts of this single custody dispute. What is at stake is the credibility of an entire court system that permits compromised actors to shape outcomes without accountability. A custody judgment is not simply another judicial disposition; it is an order that affects the core constitutional rights of parents and the fundamental well-being of children. If a domestic relations court allows a judge to rule on a case after her neutrality has been compromised, or empowers a GAL to act vindictively toward a parent whose only transgression is protected speech, then the court has functionally abandoned its role as a neutral arbiter. The result is a courtroom culture that rewards silence, punishes dissent, and leaves litigants at the mercy of officials who are neither monitored nor meaningfully constrained.

The remedy in this specific matter may take the form of vacated orders, a re-hearing before a neutral tribunal, or other forms of judicial redress. But the broader solution must involve a reconsideration of how GALs are screened, how judges are held accountable when conflicts arise, and how power is distributed within the courthouse itself. Transparency, ethical enforcement, and procedural rigor are not abstract ideals—they are the only safeguards against injustice in a system where the stakes are as high as the custody of a child. Without them, the promise of due process becomes little more than a legal fiction.

Conclusion

What began as a custody proceeding has transformed into a case study in how unchecked power, personal bias, and systemic failure can erode a family’s trust in the judicial system. With Judge Sherry Glass vacating the bench and Judge James Janik now serving as a placeholder until a new judge is assigned, the case has been quietly reframed within the court as a “mess” to be managed, rather than a miscarriage of justice to be addressed. That characterization may be telling: even those within the system appear to recognize that this is no longer a typical dispute. It is a live indictment of how that system operates.

Guardian ad Litem Andrea Limberty-Davis’s own affidavit and motion to withdraw all but admit to a posture of antagonism toward the mother, citing constitutionally protected speech and online criticism as grounds for declaring herself unable to continue. Her filings read not as neutral updates from an officer of the court, but as the final shots in a personal war, one that Davis herself ignited and escalated. The hostility laced through her words is not incidental. It is evidence of a broader institutional culture in which GALs are emboldened to treat litigants as adversaries rather than as parents with rights.

The mother’s original concerns, once dismissed as the exaggerations of a “difficult” party, have now been partially validated by the very officials who once upheld the framework in question. The judge has recused. The attorney has withdrawn. The GAL has acknowledged a conflict so severe it requires her removal. If this were a criminal trial, we would call it compromised. In civil court, it’s branded an anomaly, a hiccup, a “mess.” But for the family involved, and for every litigant whose rights hang on the professionalism of public actors, it is something far more serious: it is a warning.

This is not just about the mother’s speech. It is about what the system did in response to it. She spoke, and they surveilled her. She documented, and they retaliated. She objected, and they sought sanctions. And when her attorney finally exited the case, it was not due to bad faith, but in silent confirmation that the mother had a point. The proceedings had ceased to function as a venue for adjudication and had become instead a campaign to punish a parent for refusing to remain silent.

When judges recuse without disclosure, when GALs weaponize their filings, and when accountability is treated as a threat rather than a duty, the rule of law gives way to something else entirely. These are not procedural flaws; they are breaches of public trust. And unless they are investigated, remedied, and prevented from recurring, the damage will not end with this one case. It will become precedent, not just in law, but in culture—a silent nod to every court officer who sees neutrality as optional and retaliation as justifiable.

The mother may be one voice, but she is not alone. The documents, the withdrawals, the recusals—all corroborate what she has insisted from the start: the system is broken, and the people breaking it are not just obscure bureaucrats, but named officials acting under the color of law. Whether Lorain County is prepared to reckon with that truth remains to be seen. But one thing is now beyond dispute: the truth is no longer confined to the file. It is public, it is documented, and it is owed a response.

Closing Bio

Aaron Christopher Knapp is a licensed social worker, an investigative journalist, and a long-standing pro se litigant with a record that spans multiple jurisdictions, including Idaho, Ohio, and Utah. His work is grounded in documentary evidence, verified public records, sworn statements, and direct encounters with the institutions he reports on, and he has built a reputation for following the trail where it leads, regardless of whether it passes through the police department, the prosecutor’s office, the courts, or the county administration. Across more than a decade of public-records litigation, appellate filings, administrative complaints, and statutory challenges, he has demonstrated a sustained ability to identify unlawful processes, uncover suppressed records, expose procedural contradictions, and force public bodies to comply with the basic legal obligations that many would prefer to ignore. His reporting integrates legal analysis, first-person accountability documentation, and a clear understanding that public institutions, despite their power, remain bound by rules that most citizens never have the opportunity, the knowledge, or the resolve to test.

Aaron’s professional background includes a Bachelor of Science in Social Work from The Ohio State University, licensure as a Social Worker in the State of Ohio, and certification as a Chemical Dependency Counselor Assistant, and he has served in multiple systems that require the application of statutory interpretation, ethical evaluation, and the ability to navigate high-conflict disputes that involve law enforcement, courts, schools, guardians ad litem, clinicians, and public agencies. His experience as a veteran, a parent who litigated across three states, a GAL program appointee, and an investigative writer has shaped an approach that is both disciplined and unafraid. His work has appeared in Lorain Politics Unplugged, NewsBreak, Substack, and other platforms that prioritize government transparency, and he continues to serve as a public-records litigator who challenges unlawful denials, publishes concealed material, and documents retaliation when officials attempt to weaponize their offices against him or others.

He writes with one consistent philosophy: the truth is not negotiable, public institutions work for the people, and sunlight never hurts anyone who is doing their job lawfully.

Legal Disclaimer

The analysis provided in this report is based entirely on publicly available documents, sworn testimony, recorded statements, court filings, and information obtained through lawful public-records requests. Nothing contained in this publication constitutes legal advice, nor should it be relied upon as legal guidance, representation, or counsel. Readers who require legal advice should consult a licensed attorney who can evaluate the facts of their situation within the governing jurisdiction. All individuals and public officials discussed herein are presumed innocent unless and until they are proven guilty in a court of law, and all references to potential misconduct reflect commentary, opinion, or analysis derived from the available public record. This material is presented for investigative, journalistic, educational, and public-interest purposes, consistent with the protections of the First Amendment the rights of citizens to examine and critique the operation of their government.

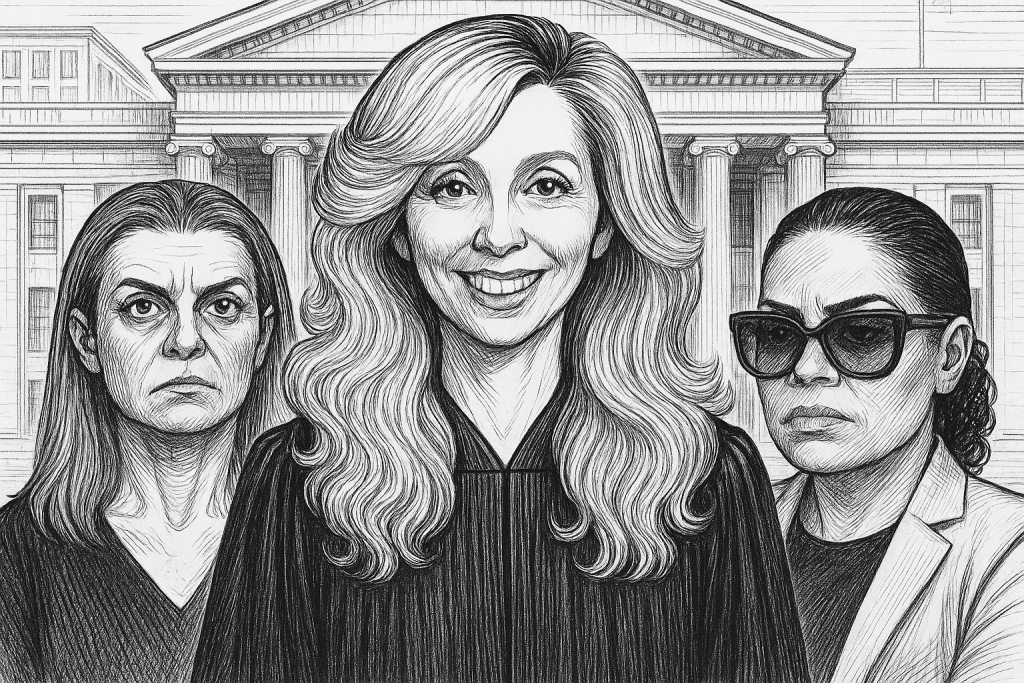

AI Image Disclaimer

The illustration used in this article is an AI-generated artistic rendering created for editorial and illustrative purposes only. It is not a real photograph. While the likenesses are inspired by publicly available images or descriptions, the depiction is not exact and should not be interpreted as an authentic or documentary image of any individual.