Thirteen Years of Unchecked Power: How a Municipal Judge Turned Contempt Law Into a Private Tool of Control

A documented pattern of unlawful contempt sentences, rewritten statutes, and a court culture that allowed one judge to bypass every safeguard the Constitution requires

By Aaron Christopher Knapp | LorainPoliticsUnplugged.com

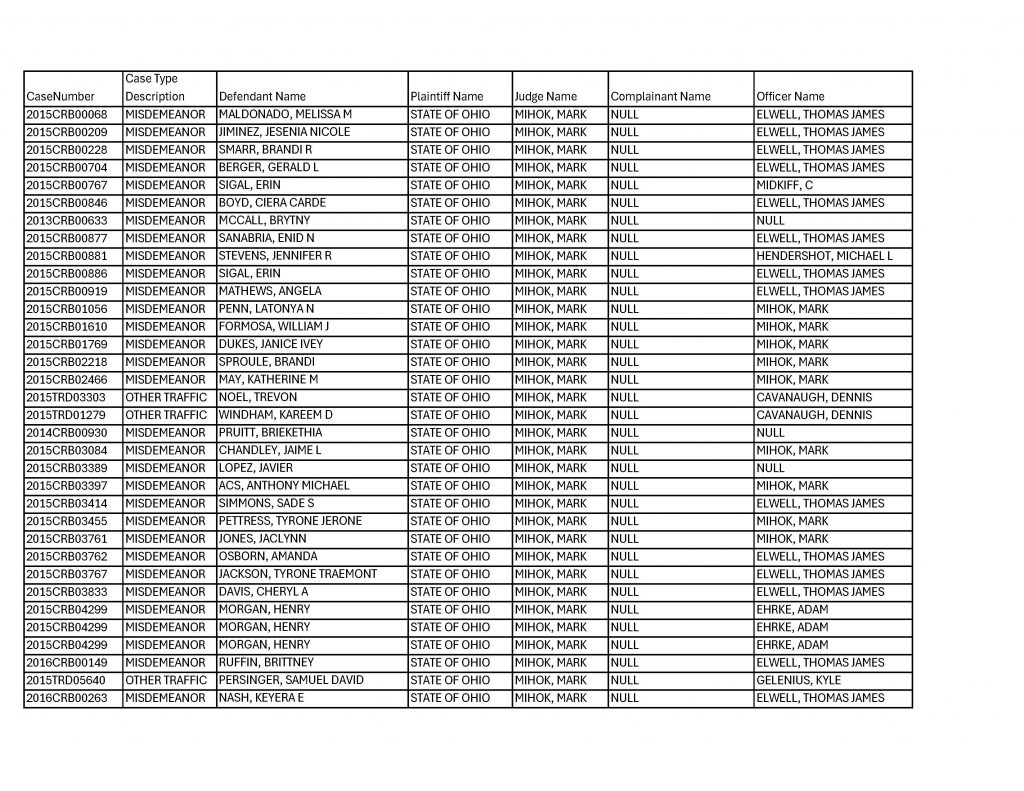

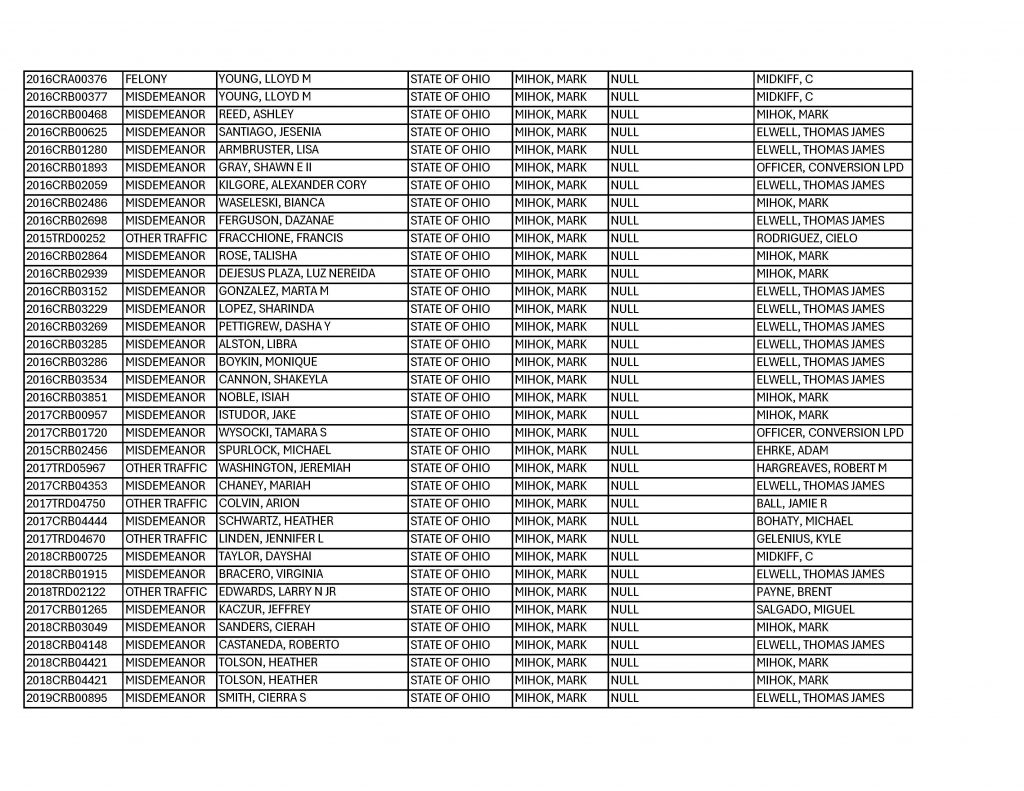

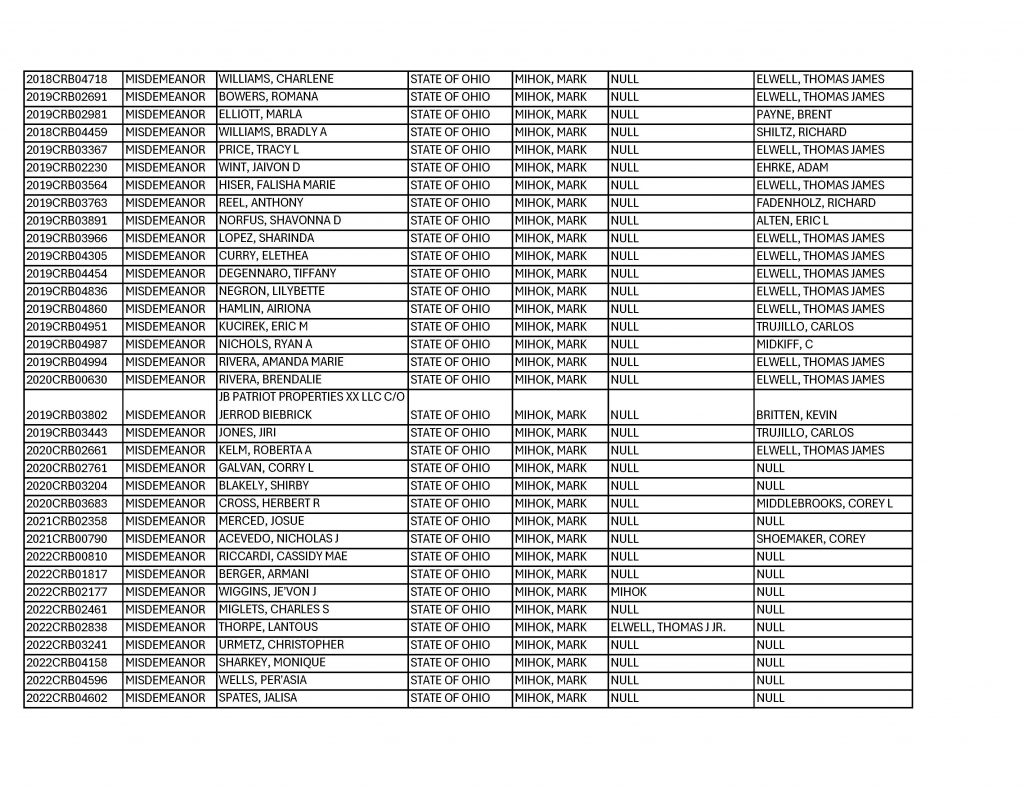

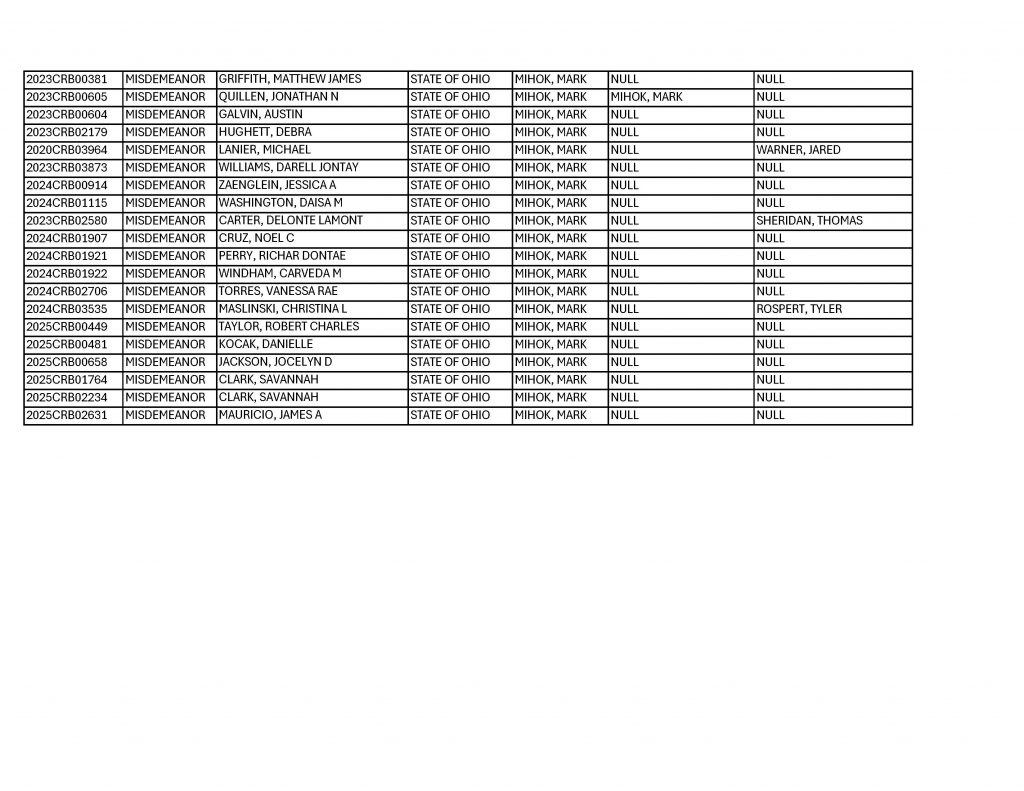

There are patterns of misconduct that hide in plain sight not because they are invisible, but because the people harmed by them do not have the resources, standing, or political oxygen to challenge them. For thirteen years, while most of Lorain County went about its daily life unaware, Judge Mark Mihok operated a contempt system that did not resemble anything written in the Ohio Revised Code, anything taught in a courtroom administration seminar, or anything contemplated by the Constitution of the United States. It was a system built out of habit, repetition, and the quiet confidence that no one would ever gather the records, cross-reference the entries, or follow the paper trail from the first illegal contempt in 2009 to the last one filed before anyone started asking questions. The contempt logs we now have show a judicial pattern so consistent and so far outside the boundaries of due process that it reads less like a docket and more like an internal blueprint for a court that functioned on its own rules, untethered from the law.

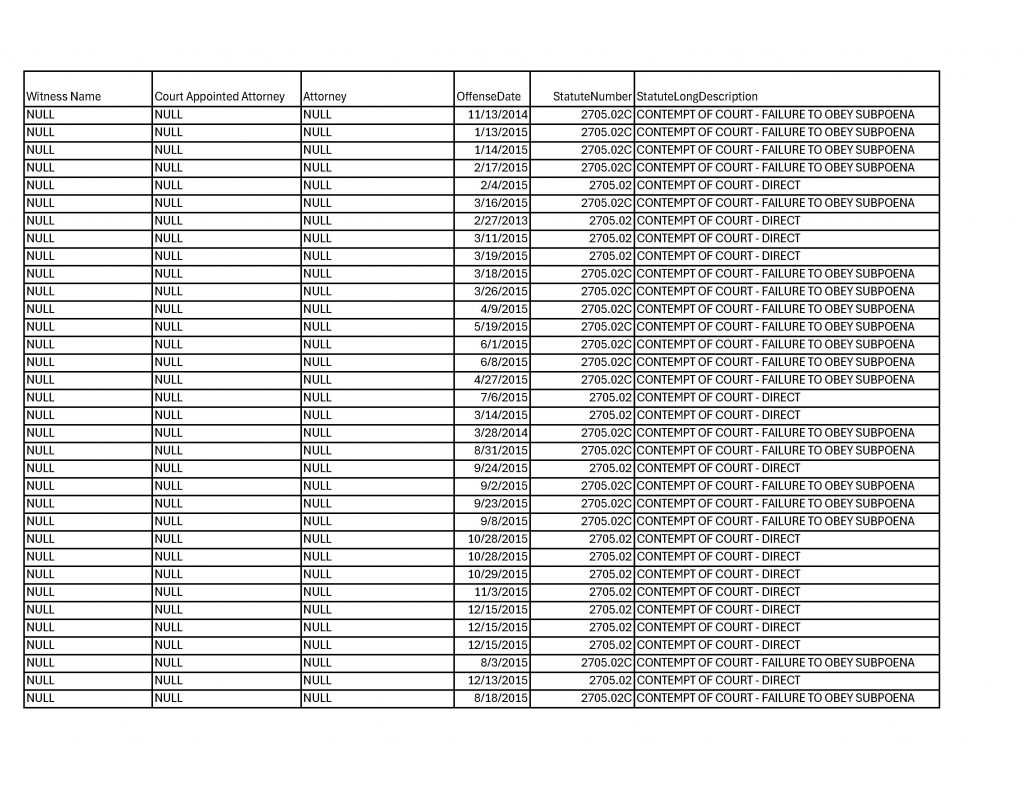

This story is not about one bad day in a courtroom. It is not about one defendant losing his temper or one emotional outburst in front of the bench. It is about a judge who repeatedly and systematically mislabeled indirect contempt as direct contempt, then used that mislabeling to impose jail time instantly without hearings, without counsel, without notice, and without any of the protections required by R.C. 2705.02, R.C. 2705.03, Criminal Rule 37, or the Due Process Clause. The files I have gathered, which span more than a decade, contain page after page of entries where the contempt box is checked for conduct that did not occur in the courtroom, was not witnessed by the judge, was not disruptive to proceedings, and did not fall under the limited category of behavior that may be punished summarily. Instead of following the law, the court adopted a pattern of writing the word “direct” on contempt forms as if the label itself created jurisdiction. The logs reveal a truth that has been buried for years. Summary contempt was imposed for failures to appear. Summary contempt was imposed for probation violations. Summary contempt was imposed for missed payments and scheduling errors. These actions cannot be punished as direct contempt under any reading of Ohio law, yet the court repeatedly treated them as if they could.

The more one studies the logs, the more unmistakable the pattern becomes. This was not a judge making a one-off mistake or misunderstanding a statute. This was a judge who created a parallel enforcement system where the line between direct and indirect contempt no longer existed. By writing the word “direct,” he erased the procedural rights the law requires. He eliminated the need for service of a complaint. He eliminated the right to counsel. He eliminated the right to a hearing. He eliminated the requirement that the court enter findings of fact. He eliminated the right to present evidence. And because summary contempt is traditionally unappealable unless the defendant moves quickly, he eliminated any realistic pathway to challenge the sentence. Most people who were jailed under this system never appealed, never filed a motion, never knew the sentence was illegal, and never had access to anyone who could explain that they had been punished under a statute that did not apply.

The most disturbing portion of the entire contempt archive is the section showing hundreds of entries where failures to appear were treated as direct contempt.

Under Ohio law, failure to appear has never been direct contempt.

A judge cannot see a defendant fail to show up. A missed appearance is not an in-court disruption. It is not conduct in the judge’s presence. It is not behavior that requires instant action to preserve order. Yet for more than a decade, Lorain Municipal Court treated failure to appear as if it were the same thing as screaming profanity in open court or threatening a witness in front of the judge. The Revised Code draws a bright line between direct and indirect contempt because direct contempt is the only time the law allows the judge to skip every safeguard and impose punishment on the spot. When a judge takes an act that must follow the indirect contempt procedures and reclassifies it as direct contempt, the judge strips away every constitutional protection the Ohio Supreme Court requires. That is what happened here. Not once. Not twice. But over and over for more than a decade.

This pattern continued uninterrupted until the James Mauricio case forced a crack into the process. When Mauricio was summarily jailed for an alleged out-of-court act, the filings that followed finally forced the court to face something most defendants never had the chance to raise. The law does not authorize this. The judge did not have jurisdiction to impose summary punishment. The sentence was illegal the moment it was pronounced. The Mauricio habeas filings brought something into daylight that had never been properly challenged before. They did not just expose one contempt. They exposed the existence of a system that had been operating in violation of law for years.

Part 2 of this investigation is not a rehash of legal theory. It is a presentation of evidence. It is an account of how a single judicial officer created practices that deviated from every rule on the books. It is a look at how ordinary people were jailed without hearings. It is the beginning of accountability for a decade of unlawful punishment imposed under the authority of a judge who believed the word “direct” was a key that unlocked powers the law never gave him. It is a story that has been waiting thirteen years to be told.

I. A Court That Quietly Drifted Outside the Law

There are patterns of misconduct that hide in plain sight not because they are difficult to detect but because the people caught in their path rarely have the ability to challenge them. For thirteen years, while Lorain County remained largely unaware, Judge Mark Mihok operated a contempt system that bore almost no resemblance to the one the Ohio legislature enacted or the one the Ohio Supreme Court repeatedly interpreted. It was a system carried out through routine entries and repetitive language, a system that blended into the background noise of a busy municipal docket, and a system that could only persist because the defendants caught in it lacked standing, resources, counsel, or a platform to expose what was happening.

The local rules of the Lorain Municipal Court present a façade of normalcy. They incorporate the Rules of Superintendence and the Ohio Rules of Criminal Procedure. They contain nothing unusual that expands contempt power or allows summary punishment without process. Yet the contempt logs covering the years 2009 through 2023 reveal a completely different reality. Page after page shows defendants charged with direct contempt for conduct that did not occur in the courtroom, was not witnessed by the judge, and did not qualify under any interpretation of R.C. 2705.01. The files show a judge who repeatedly imposed jail time instantly, without hearings, without findings, and without due process. What emerges is a parallel system of judicial punishment that existed outside the statutory text and outside the constitutional framework that governs contempt proceedings.

This investigation is not about a single incident or a single defendant. It is about a structure that operated without oversight, without challenge, and without compliance with the most basic legal requirements. The story begins with the law itself.

II. The Legal Rules That Should Have Stopped This Before It Began

Ohio law does not merely separate direct contempt from indirect contempt. It enforces that separation with a precision that leaves no room for improvisation. The statute governing direct contempt, R.C. 2705.01, applies only when the misconduct occurs in the presence of the court and disrupts judicial proceedings in a way that requires immediate intervention. The law contemplates situations where the judge personally observes the conduct and must restore order without delay. Even under those narrow conditions, courts have long required a written entry describing the actions that occurred and the factual basis for punishment. Direct contempt is intended to be used sparingly, only when the conduct poses a real and immediate threat to the administration of justice.

Indirect contempt, governed by R.C. 2705.02, covers everything that does not occur in the courtroom before the judge’s eyes. This includes failure to appear, disobedience of court orders, violations of bail conditions, nonpayment issues, and conduct that takes place outside the judge’s presence.

The statute does not treat these matters as emergencies. It treats them as due process events that require a written charge, formal service, an evidentiary hearing, the right to counsel, the opportunity to present testimony and mitigating circumstances, and a written entry containing findings of fact. The due process structure is not ceremonial. It is the mechanism that prevents courts from jailing citizens without lawful authority.

Ohio Supreme Court precedent makes the distinction unmistakable. In In re Davis, the Court held that summary punishment is permitted only when the judge personally witnesses the allegedly contemptuous conduct inside the courtroom.

In State v. Kilbane, the Court ruled that indirect contempt requires full procedural safeguards and that a failure to follow those procedures deprives the court of jurisdiction to impose punishment.

In Cincinnati v. Cincinnati District Council 51, the Court explained that a court cannot transform indirect contempt into direct contempt simply by labeling it direct, because jurisdiction does not arise from the judge’s description but from the underlying facts.

In Cleveland v. Ramsey, the Court again reaffirmed that out-of-court behavior cannot be summarily punished and that any sentence imposed without adherence to the statutory process is void. These rulings are not advisory or discretionary. They define the boundary between legitimate judicial authority and unlawful deprivation of liberty.

Failure to appear stands at the center of this legal framework. Courts across Ohio have consistently held that failure to appear cannot be punished as direct contempt because the judge does not personally observe the absence. It happens outside the courtroom. It does not constitute an in-court disruption. And it does not require immediate summary action. It must always be handled as indirect contempt under R.C. 2705.02, with full adherence to the statutory procedures. When a judge ignores those requirements, the judge exceeds jurisdiction, and any resulting sentence is legally void.

In reviewing the contempt records from the Lorain Municipal Court, the departure from these rules is unmistakable. The logs show repeated entries where conduct that did not occur in the courtroom was labeled as direct contempt. They show summary punishment imposed for failures to appear, despite the fact that Ohio law has never recognized failure to appear as direct contempt. They show jail sentences imposed without written charges, without service, without hearings, without counsel, and without findings of fact. They show a pattern of reclassifying indirect contempt as direct contempt in a way that eliminated every procedural safeguard required by statute and rule.

The Ohio Supreme Court has warned for decades that jurisdiction cannot be created by description. A judge cannot convert indirect contempt into direct contempt merely by calling it direct. Jurisdiction arises from the facts of the conduct, not the label the judge chooses to write in a docket entry. When a judge imposes summary punishment for conduct that does not meet the statutory definition of direct contempt, the judge acts outside the authority granted by law. The sentence is void on arrival. It never possessed legal force.

With these rules in place, the contempt logs should contain careful distinctions, references to hearings, documentation of service, entries reflecting due process, and written findings that align with statutory requirements. Instead, the logs show the opposite. They show a system where the statutory boundaries were ignored, where due process was bypassed as a matter of routine, and where summary punishment was imposed in circumstances that the law explicitly prohibits. They reveal a court where the definition of contempt was not governed by the Ohio Revised Code or by Supreme Court precedent, but by unilateral decisions that contradict both.

III. The Contempt Logs That Reveal the Hidden System

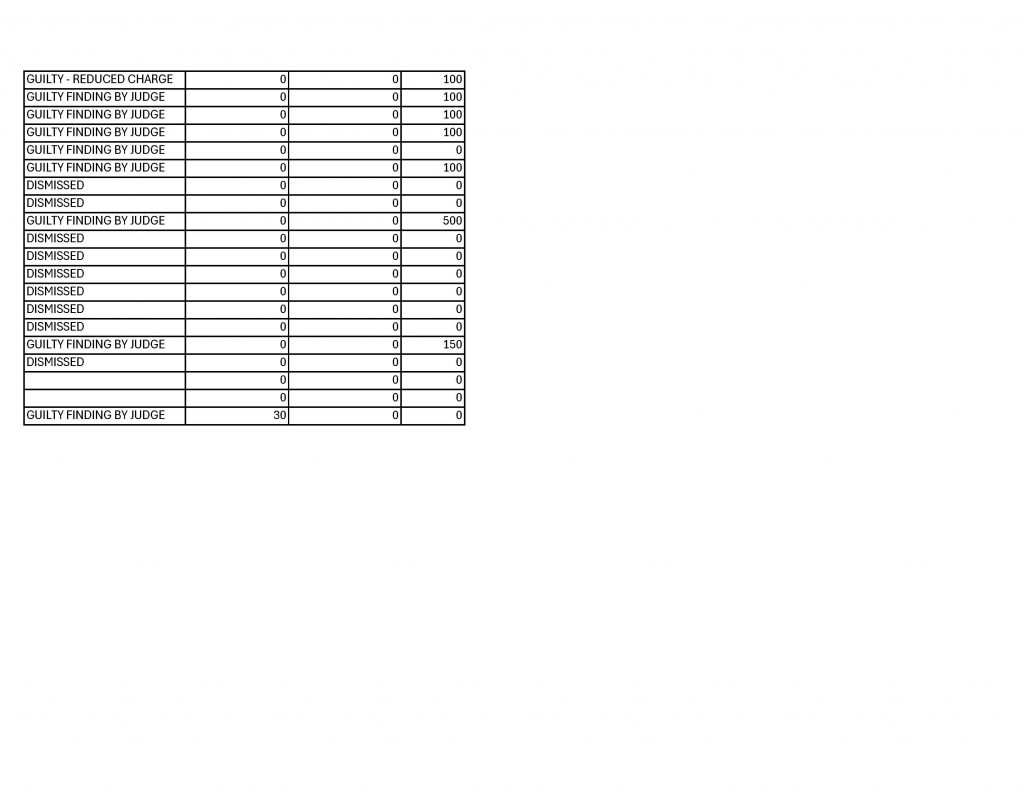

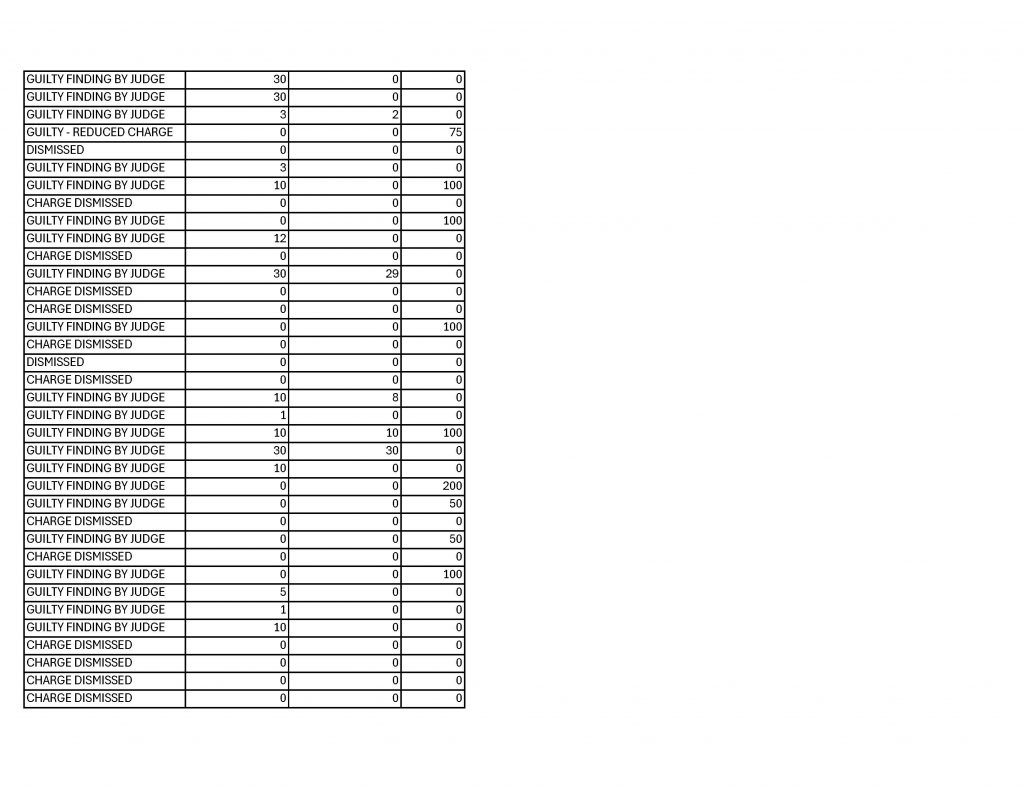

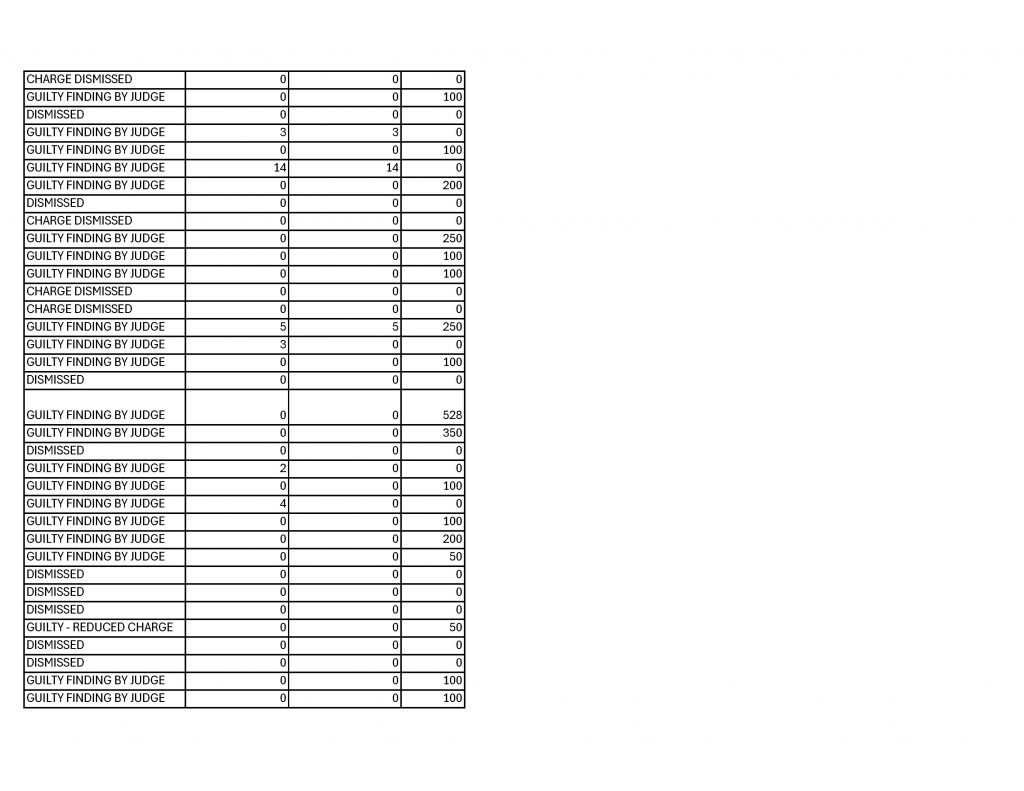

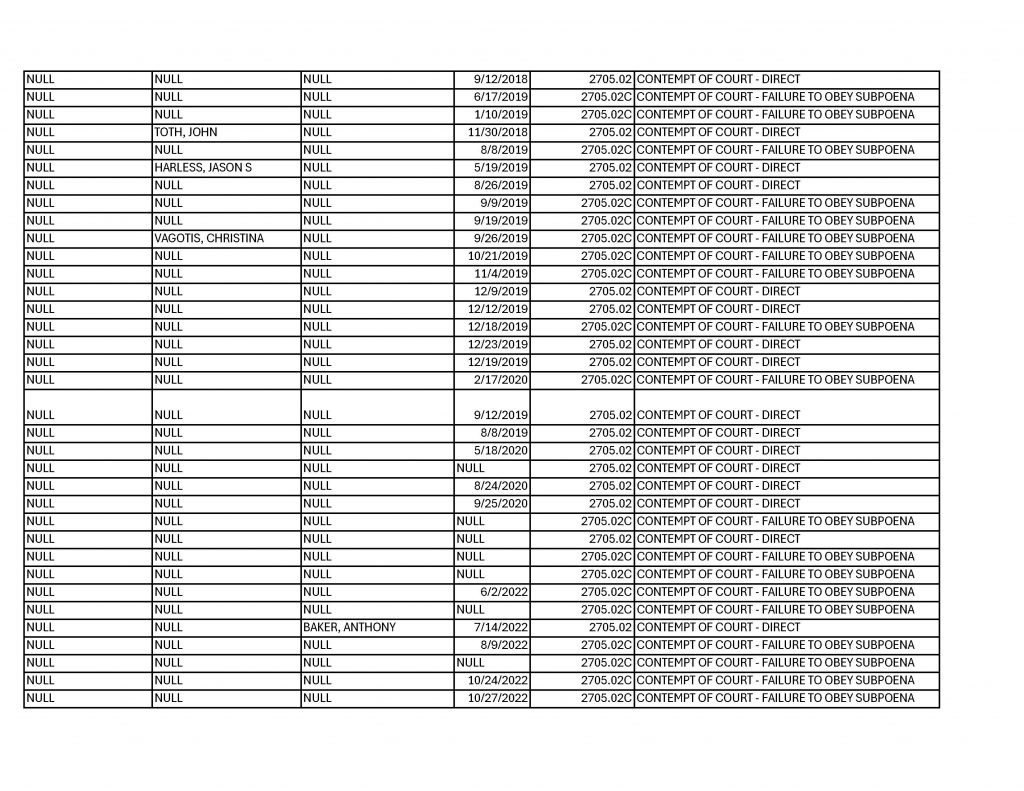

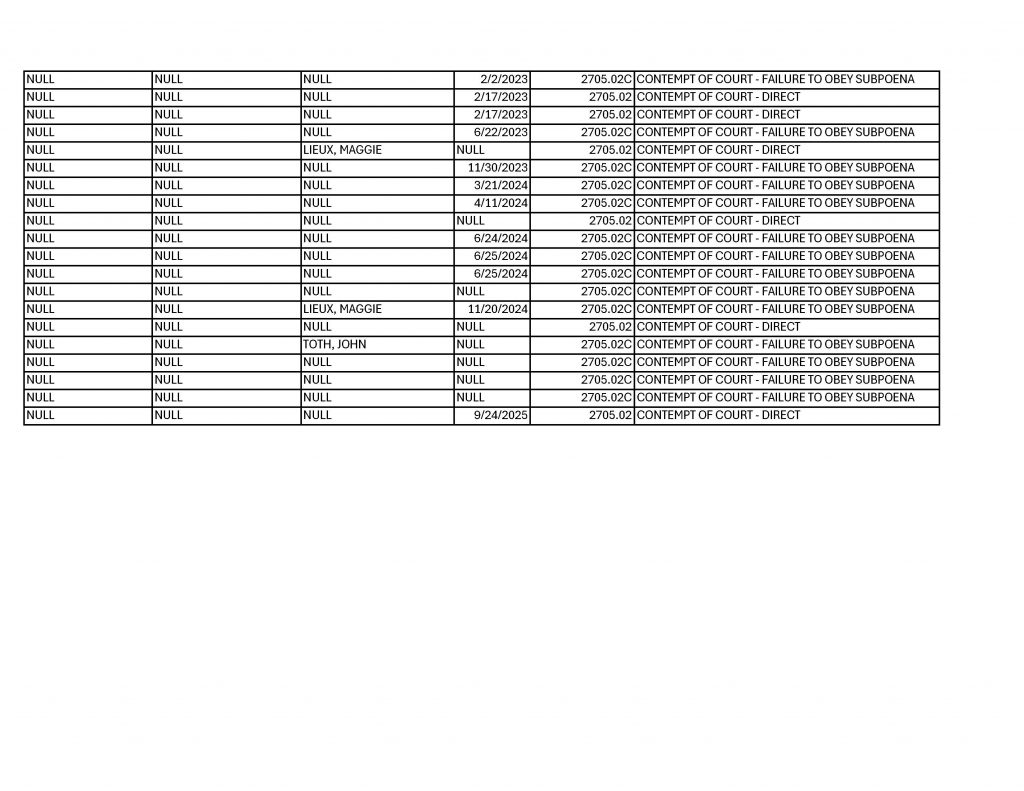

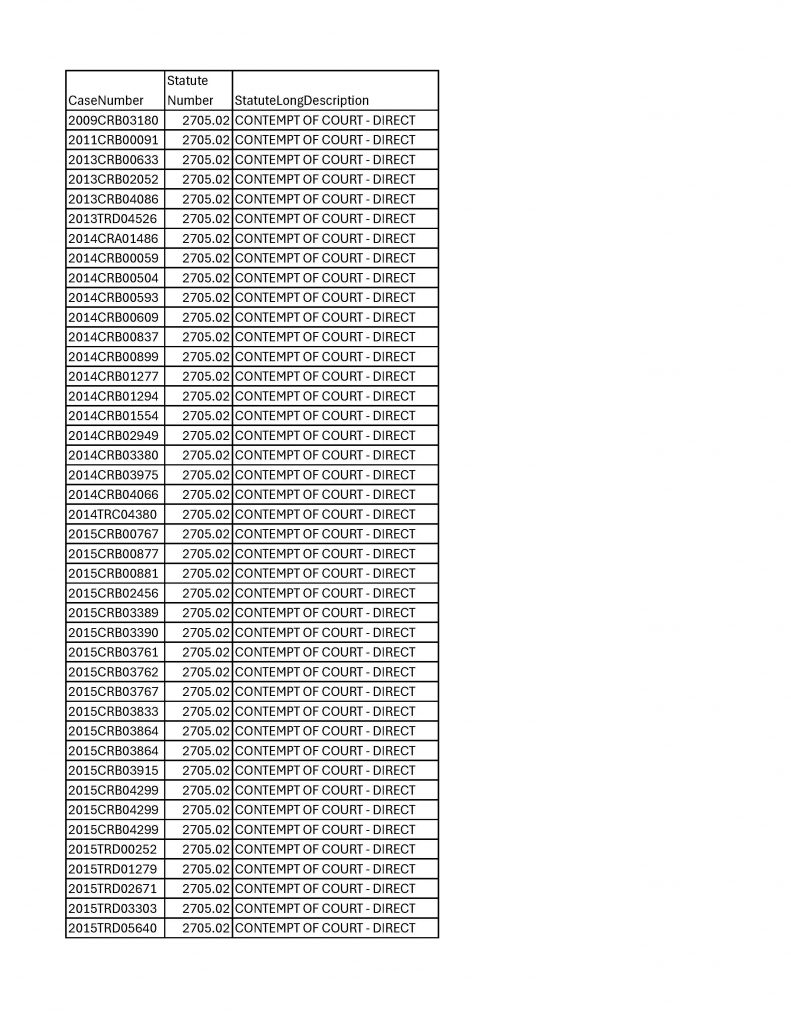

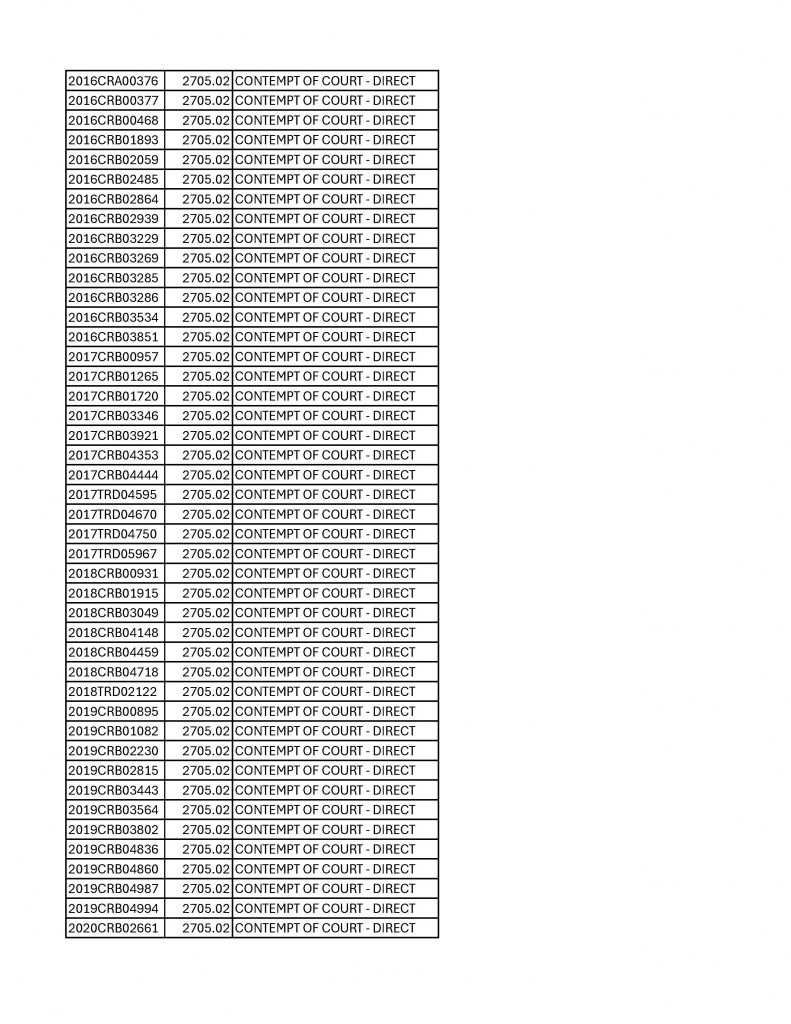

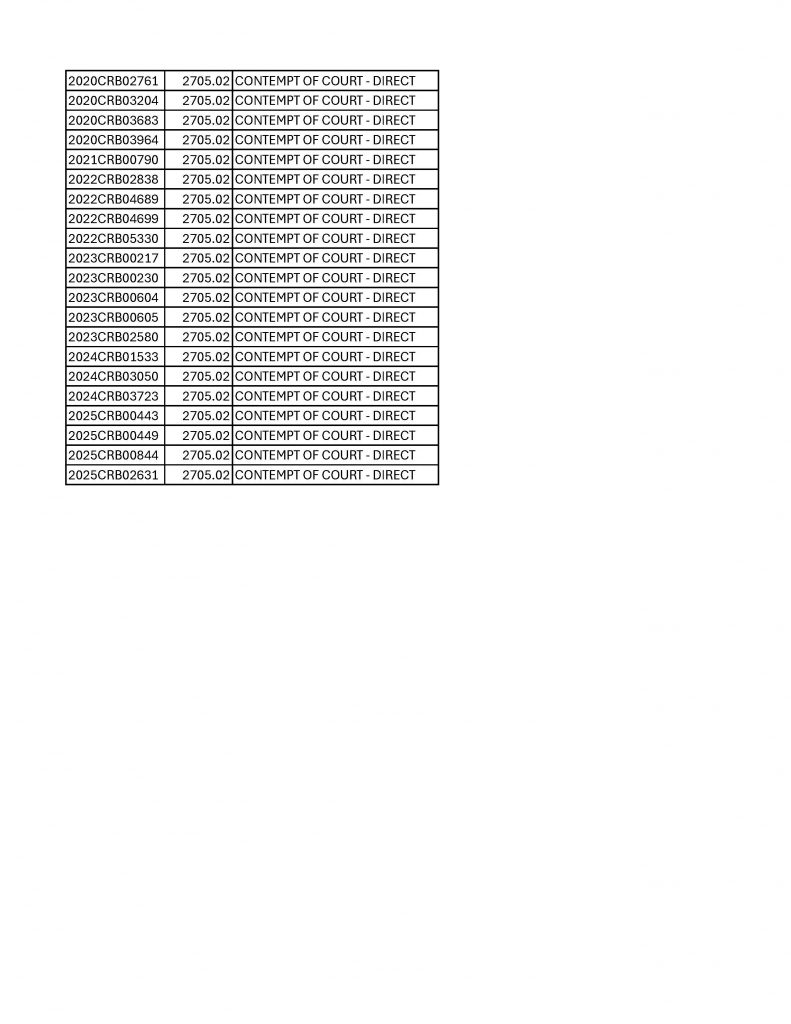

When the contempt logs covering the years 2009 through 2023 are placed side by side, the pattern that emerges is not subtle. It is not complicated. It is not buried in obscure footnotes or hidden behind ambiguous language. It is written plainly, in uniform formatting, across hundreds of entries that list the same statutory citation and the same classification of contempt.

The logs display a judicial routine in which the label “direct contempt” appears next to conduct that did not occur in the courtroom and could not have been personally witnessed by the judge.

The entries span criminal cases, traffic cases, probation matters, and missed appearances. In each instance, the court designated the conduct as direct contempt under R.C. 2705.02, even though R.C. 2705.02 is the statute governing indirect contempt.

The repeated combination of the term “direct” with the statute for indirect contempt reflects not just a misunderstanding of the law but a wholesale redefinition of it.

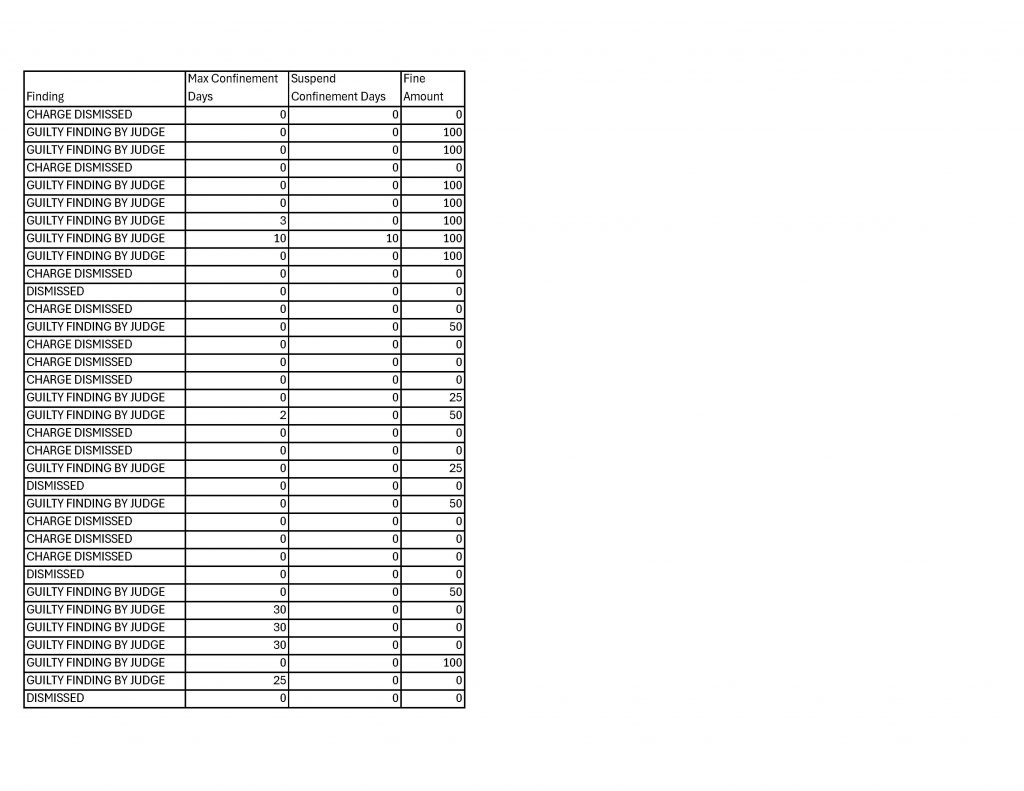

The mislabeling is not sporadic. It is systematic. The logs list direct contempt findings for failures to appear, which is conduct that necessarily takes place outside the courtroom and therefore cannot satisfy the statutory elements of direct contempt. They list direct contempt findings for probation violations, which again occur outside the presence of the judge. They list direct contempt findings for nonpayment and scheduling issues, all of which fall explicitly within the categories that the law treats as indirect contempt. In case after case, the court dispensed with the procedures required for indirect contempt by assigning the conduct the label “direct” and imposing jail sentences immediately. The entries do not reference hearings. They do not reference findings of fact. They do not reference written charges or service. They reflect a court that operated under a presumption that procedural steps could be bypassed simply by redefining the nature of the contempt.

The breadth of the pattern is stark. The logs show more than a decade of sentencing entries where defendants were taken into custody based solely on the judge’s classification of their conduct as direct contempt, even though the facts described in the underlying cases could never justify summary punishment. The law requires that summary punishment be reserved for conduct that threatens the authority or functioning of the court in real time. Yet the entries demonstrate that summary punishment became the default response to any perceived noncompliance, regardless of where the conduct occurred or whether it posed any disruption to courtroom proceedings. This practice did more than violate procedural rules. It inverted the entire structure of contempt law by making summary punishment the norm rather than the exception.

Even without the statutory framework, the logs themselves reveal internal inconsistencies. Many entries list the charge as a violation of R.C. 2705.02 but label the contempt as direct. R.C. 2705.02 cannot support a direct contempt finding. It is the statute that governs indirect contempt and requires full due process. The court’s consistent pairing of the statute for indirect contempt with the designation of direct contempt shows that the classification was not grounded in the controlling law. It was a template applied across cases without regard for the underlying facts. The uniformity of the entries across so many years demonstrates that this was not an occasional mistake but a standardized practice.

The logs also reflect a near total absence of the procedural steps required under Ohio law. There is no indication that defendants received written notice of the allegations against them. There is no record of service. There is no notation of hearings where evidence could be presented or challenged. There is no documentation that counsel was provided or waived. The absence of these steps in case after case shows that the court was not attempting to comply with the requirements of indirect contempt proceedings. It was avoiding those requirements entirely by reclassifying indirect contempt as direct.

A court’s docket is the official record of its actions, and the contempt logs serve as a chronicle of judicial decision making. In this case, that chronicle shows a judge who acted outside the jurisdiction granted by statute and rule. The logs display a longstanding pattern of summary punishment imposed without legal authority. They reveal a system where the distinction between direct and indirect contempt was effectively erased, not by legal reasoning but by a repetitive practice of mislabeling. They show that the due process protections guaranteed by Ohio law were not merely overlooked. They were bypassed intentionally, in case after case, for more than a decade.

The logs provide the clearest evidence of how the court functioned during the period in question. They show the consistency of the misapplications. They show the standardization of unlawful procedures. And they show the scale of the issue, extending across hundreds of defendants and countless sentences. In any other context, such a sustained departure from statutory requirements would trigger oversight, audit, or appellate intervention. In this instance, it continued without interruption until the system was finally challenged directly through litigation. The logs are not theoretical indicators of a problem. They are the documentation of the problem itself.

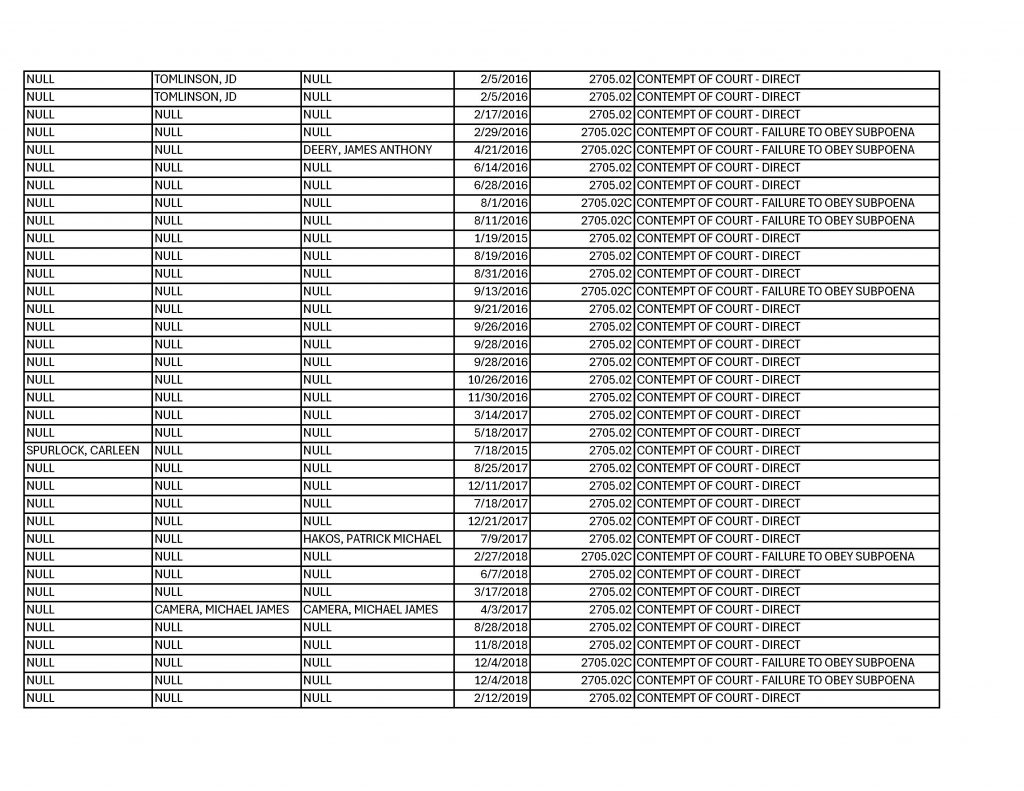

IV. The Failure to Appear Pipeline That Allowed Illegal Sentences

The most revealing part of the contempt logs is the sequence of entries showing that failure to appear became the court’s primary gateway into summary punishment. Anyone familiar with contempt law in Ohio knows that failure to appear has never been classified as direct contempt. The Ohio Supreme Court has repeated this point so many times that it is considered settled law. A judge cannot personally witness someone failing to show up. The absence takes place outside the courtroom and therefore cannot be punished summarily. Yet the logs from the Lorain Municipal Court show that absence itself was transformed into a trigger for immediate jail time. What should have been handled through indirect contempt procedures was instead folded into a routine of summary sentencing.

This pipeline operated with remarkable simplicity. A defendant missed a court date. The court did not issue a show-cause order or a formal contempt complaint. It did not set a hearing or notify the defendant of the allegations. It did not follow the statutory requirements of R.C. 2705.02 or R.C. 2705.03. Instead, the court entered a finding of direct contempt and imposed jail time at the next point of contact, whether that was a future court appearance or an arrest on an unrelated matter. The judge treated the failure to appear as if it had occurred in open court, as if it had disrupted proceedings, and as if he had personally observed the conduct. The law does not authorize this approach. The facts do not support this approach. But the logs confirm that this approach became standard practice.

Ohio courts have been explicit about the legal status of failure to appear.

In In re Davis, the Supreme Court held that conduct not witnessed by the judge cannot support a direct contempt finding.

In State v. Kilbane, the Court reiterated that indirect contempt requires full procedural protections and that any attempt to shortcut those protections renders the proceeding void.

The Court in Cleveland v. Ramsey reaffirmed that judges may not expand summary contempt powers beyond the narrow circumstances set forth in R.C. 2705.01. These cases, taken together, draw a strict boundary: absence is never direct contempt and cannot be punished without adherence to the formal process for indirect contempt.

The logs show that this boundary was ignored. They list failures to appear as direct contempt in a way that strips away any possibility of viewing these actions as isolated errors. The practice was repeated year after year, across multiple case types, with no apparent regard for the statutory distinction. The consequence was immediate incarceration without process. The court did not ask why the defendant was absent. It did not allow the defendant to present mitigating evidence. It did not inquire into notice issues, transportation problems, or clerical mistakes. It simply imposed jail time as a default response to absence.

This approach had a cascading impact on defendants. People were jailed not because their conduct met the legal standard for summary contempt but because the label “direct” had been stamped onto their cases. The classification served as a legal shortcut that bypassed the protections the statute requires. The punishment that followed did not flow from lawful authority. It flowed from a system that treated absence as in-court defiance and nonappearance as a disruption of proceedings, even though neither description matched the facts.

The pipeline also had broader structural effects. When failure to appear becomes a basis for summary punishment, the court gains power to jail individuals without hearings, without counsel, and without evidence. This converts a minor procedural issue into a mechanism of incarceration. It places enormous coercive power in the hands of the court and removes the procedural safeguards designed to prevent arbitrary or mistaken punishment. In the Lorain Municipal Court, according to the logs, this power was not exercised sparingly or reluctantly. It was exercised routinely.

The absence of hearings in these cases is particularly telling. Under R.C. 2705.02, an indirect contempt hearing serves as the gateway to any lawful punishment. At that hearing, the defendant has the right to contest the allegation, challenge the facts, and explain the circumstances. For many defendants, such hearings reveal that the failure to appear was caused by illness, transportation issues, notice failures, or other factors beyond the defendant’s control. By skipping the hearing, the court eliminated the opportunity to determine whether punishment was warranted or lawful.

The practice also disproportionately harmed unrepresented defendants. Many of the individuals who faced these contempt charges did not have counsel. They lacked the information and resources to challenge the judge’s classification or to understand that the punishment imposed was legally impermissible. Without counsel, defendants were left with no meaningful way to assert the protections guaranteed by statute and case law. The absence of legal representation made the pipeline even more entrenched, as few individuals were in a position to recognize that their contempt sentence was void.

A failure to appear pipeline should not exist in any Ohio court. It contradicts the structure of the contempt statutes. It contradicts controlling case law. It contradicts the constitutional requirement of due process. Yet the contempt logs show that Lorain Municipal Court relied on this pipeline for more than a decade. This was not the exception. It was the rule. And it formed the backbone of a contempt system that operated outside the confines of the law.

V. The Human Cost of Summary Punishment Without Process

Every contempt entry in the logs represents a living person who walked into the Lorain Municipal Court unaware that the most fundamental protections of due process had already been stripped away before they arrived. Each entry is a story of someone who faced jail time not because the law required it, not because a hearing justified it, and not because their actions met any recognized legal threshold for summary punishment, but because the court treated the statutory word “direct” as if it were a universal key that opened the door to immediate incarceration. The human consequences of this unauthorized system were not confined to a single afternoon in a courtroom. They rippled outward into jobs, families, transportation, finances, mental health, and every other part of ordinary life that collapses when someone is taken into custody without warning.

The people caught in this system were not criminals facing violent charges. They were individuals coming to court for traffic matters, misdemeanor cases, probation reviews, and minor disputes. Many were struggling with poverty, transportation problems, unstable housing, untreated health issues, or the everyday chaos that can derail a court appearance. Some relied on mailed notices that never arrived. Some relied on outdated court calendars or confusing continuance slips. Others missed hearings because of conflicting court dates in other jurisdictions, a common occurrence in municipal systems. Yet when they returned for their next hearing or when they encountered law enforcement for entirely unrelated reasons, they were told that they had been found in direct contempt and that the punishment was already waiting for them.

A single night in jail is enough to destabilize a person’s life. Many people cannot afford to miss a shift. Many live paycheck to paycheck. A missed day of work can trigger lost wages, disciplinary actions, or termination. A single arrest can cause someone to lose childcare, lose housing, or fall behind on bills. For some, the consequences escalate quickly. A towed vehicle may not be recoverable. A missed appointment with a social service provider may lead to termination of assistance. A probation violation triggered by an unlawful jail term can lead to further consequences in other courts. The logs spanning thirteen years demonstrate that these cascading harms occurred repeatedly and predictably. They show a system in which the consequences of an unauthorized contempt sentence extended far beyond the short entries typed into the docket.

The absence of hearings removed any chance to correct mistakes before they became life-altering. A hearing is where defendants can explain that they never received notice, that transportation failed, that childcare collapsed, that the date was confused, or that an attorney misinformed them. A hearing is where clerical errors are discovered, where scheduling conflicts are resolved, and where judges learn the context that could change the outcome. When hearings are removed from the process, so are these safeguards. When hearings are removed, the court stops operating as a forum for fact-finding and starts operating as a conveyor belt for punishment.

The harm is not only practical but constitutional. Summary punishment for indirect contempt is a deprivation of liberty without due process of law. The right to be heard is foundational to the American legal system. It is not a formality. It is a constitutional guarantee that separates a judicial proceeding from arbitrary detention. When defendants are punished without hearings, the court denies them the opportunity to defend themselves, to contest allegations, to present evidence, and to seek counsel. It strips them of the legal tools that give meaning to the presumption of innocence and the right to contest state action. For many individuals in the Lorain Municipal Court, these rights never existed in practice because the court never provided the process required by law.

The emotional toll of sudden incarceration is equally profound. Many defendants in municipal courts suffer from mental health issues, anxiety, trauma, or chronic instability. Being taken into custody unexpectedly, often in front of family members or children, intensifies these struggles. People already living with fragility suddenly face the stark reality of confinement, uncertainty, and fear. For some, the experience shapes their view of the justice system permanently. It teaches them that courts are places where punishment arrives before explanation, where the judge has total power, and where their voice has no place. It reinforces distrust in public institutions and widens the gap between the community and the legal system meant to serve it.

These harms reverberate through families as well. A parent who is jailed unexpectedly leaves children without care. Relatives scramble to fill the gap, and sometimes no one is available. Schools call to ask why a child was not picked up. Employers call to ask why an employee did not show up. Financial obligations go unmet. Even after release, the fallout continues. The defendant must navigate lost wages, replacement fees for impounded vehicles, court costs, and the emotional burden of uncertainty about what will happen next. And all of this occurs without the defendant ever being given a lawful opportunity to challenge the contempt finding.

Over thirteen years, the repeated use of summary punishment created a quiet crisis that never reached the surface because the people most affected lacked the ability to contest it. They lacked attorneys. They lacked money. They lacked transportation. They lacked stability. They lacked knowledge of the law. And without those resources, they lacked the means to bring attention to the unlawful practices that shaped their interactions with the court. The silence of the people harmed by the system became a shield that allowed the system to continue.

It is easy for judicial misconduct to remain invisible when the people harmed cannot raise their voices. It is easy for unlawful practices to become normalized when they unfold quietly, one defendant at a time, never drawing the attention of the public or the media. The contempt logs spanning more than a decade reflect a pattern of judgment entries that rarely sparked outrage because each case seemed small in isolation. Yet when viewed collectively, they reveal a systemic practice that inflicted profound harm on individuals, families, and the community. These were not isolated mistakes. They were the predictable outcome of a contempt system that operated outside the law.

This human cost is the backdrop to the legal violations. It is what gives weight to the statutory requirements and the constitutional protections that were ignored. The rules exist to prevent exactly the kind of harm that occurred in Lorain Municipal Court. When the rules were bypassed, the consequences were not theoretical. They were felt in households, workplaces, schoolyards, and neighborhoods across the city. They accumulated quietly, case by case, until the pattern became undeniable.

VI. How the Mauricio Case Pulled the Curtain Back on Thirteen Years of Violations

The contempt system inside the Lorain Municipal Court might never have been exposed if not for the unusual circumstances surrounding the case of James Mauricio. For more than a decade, the court’s summary contempt routine had gone unchallenged. Most defendants lacked counsel. Most did not know that the procedure imposed upon them violated statutory and constitutional law. Most endured their sentences quietly and moved on, unaware that the punishment they received was void the moment the judge imposed it. The system remained intact not because it was lawful but because no one had ever forced it into the kind of legal scrutiny that could unravel it. The events surrounding Mauricio changed that dynamic in a way the court could not control.

Mauricio’s case began as another routine contempt incident, at least from the court’s perspective. Judge Mihok treated it as he had treated countless previous cases, asserting direct contempt authority where none existed and imposing summary punishment without the process required by R.C. 2705.02 and R.C. 2705.03. Yet this time, there was a critical difference. Mauricio had the presence of mind and the personal conviction to contest what had been done to him. He refused to accept a sentence that had been imposed without lawful jurisdiction. That refusal set in motion a series of filings that forced the court to confront the statutory framework it had ignored for more than a decade.

The habeas petition filed on his behalf laid out the issue in clear terms. It detailed that the judge had not witnessed the conduct that formed the basis of the contempt finding. It pointed out that the judge imposed punishment immediately, without a hearing, without notice, and without counsel. It highlighted the contradiction between the facts of the case and the statutory requirements of R.C. 2705.01 and R.C. 2705.02. It relied on case law that had defined these boundaries for generations, including In re Davis, Kilbane, and Ramsey. The petition did not rely merely on abstract legal arguments. It relied on the facts of the case and the statutory text that governs contempt jurisdiction. It stated plainly that the court acted outside of its legal authority.

The filings that followed reinforced the central point: the judge lacked jurisdiction to issue the contempt sentence because the conduct was indirect, not direct, and therefore required due process. The motions to accept the affidavit instanter, the motion for forthwith ruling under R.C. 2725.06, the motion for emergency release, and the memorandum in opposition to the respondent’s motion to strike all converged on the same premise. They forced the court to acknowledge what the contempt logs had made undeniable. The statutory requirements for indirect contempt were not followed. The contempt finding did not meet the legal definition of direct contempt. And because the judge acted outside of the authority granted by statute, the sentence imposed was void ab initio.

Once raised in a formal proceeding, these issues could not be brushed aside. The court was confronted not only with the facts of Mauricio’s case but with a pattern that had been embedded in its operations for thirteen years. The logs, the statutory requirements, and the case law created a record that was impossible to reconcile with the court’s repeated designation of indirect conduct as direct contempt. The judge could no longer rely on the assumption that no one would challenge his use of summary punishment. The legality of his entire contempt process had been placed under judicial review, and the filings forced a level of accountability that had been missing from the court for more than a decade.

Mauricio’s case also exposed the internal contradictions inherent in the court’s practice. The judge responded as if the contempt finding were routine and fully supported by law, yet the filings methodically dismantled that claim. They showed that summary punishment is permissible only when the conduct occurs in the judge’s presence. They showed that absence, scheduling issues, and out-of-court behavior cannot qualify as direct contempt. They showed that indirect contempt requires process that was never provided in this case or in the many cases documented in the logs. And they showed that the court had been operating outside the statutory structure not once but repeatedly over the span of thirteen years.

For the first time, the court’s contempt system encountered a defendant who had the legal leverage, external support, and evidentiary record necessary to force compliance with the law. The filings established that jurisdiction cannot be created by labeling a case “direct” when the facts do not support that classification. They established that summary punishment cannot be imposed for conduct that occurs outside the courtroom. They established that statutory procedures cannot be bypassed for convenience or expediency. And they established that when a court acts outside of these boundaries, the resulting sentence has no legal effect.

The Mauricio case did not reveal a single aberrant act. It revealed the architecture of a system that had functioned unlawfully for thirteen years. It illuminated what had been invisible to the public and inaccessible to the people harmed by it. It exposed the fault lines running through every contempt sentence the court issued during that period. It placed the court in a position where the only choices available were to acknowledge the legal deficiencies or to continue defending practices that could not withstand statutory or constitutional scrutiny.

Once the case entered the public record, it became impossible for the court to return to the quiet system it had built. The filings forced transparency onto a process that had relied on silence. They introduced scrutiny into a courtroom that had operated without it. And they brought into the open the reality that hundreds of defendants had been jailed under a contempt structure that was never authorized by law.

VII. Why These Sentences Cannot Survive Legal Review

When a court operates outside the boundaries of its statutory authority, the legal system does not treat the resulting orders as irregular or imperfect. It treats them as void. The distinction is critical. A void judgment is not merely mistaken or erroneous. It is a judgment issued without jurisdiction, and under Ohio law a court lacks power to enforce, defend, or justify a judgment that was void from the moment it was signed. This principle has remained constant across Ohio jurisprudence for decades. Jurisdiction arises from statutes and constitutional provisions, not from a judge’s personal interpretation of convenience or practice. When a judge misclassifies indirect contempt as direct and imposes summary punishment, the judge does not merely make a clerical mistake. The judge exceeds the authority granted by law and thereby strips the judgment of legal force.

Ohio courts have long recognized this principle. In Kilbane, the Supreme Court explained that a court has no jurisdiction to impose summary punishment for indirect contempt. In Davis, the Court reaffirmed that only conduct personally observed in the courtroom can support direct contempt. In Ramsey, the Court repeated that summary punishment is strictly limited to behavior occurring in open court and that anything outside that narrow category requires full due process. The thread running through these cases is clear. When the underlying facts do not qualify as direct contempt, the court lacks jurisdiction to impose summary punishment, and any sentence based on that approach is void.

The contempt logs from the Lorain Municipal Court show that Judge Mihok repeatedly used summary punishment in precisely the circumstances where the Supreme Court has held that summary punishment is forbidden. Failures to appear, probation problems, missed appointments, payment issues, and other out-of-court conduct cannot be reclassified into direct contempt simply because a judge decides to write the word “direct” on the docket. Jurisdiction follows the facts, not the label. When the facts describe indirect contempt, the court must follow the process for indirect contempt. And when the court does not, the resulting sentence is an act taken without jurisdiction. The law treats that sentence as a legal nullity.

This is not an abstract distinction. A void sentence cannot be enforced. It cannot survive appellate review. It can be challenged at any time, by any mechanism, in any court with authority to hear the claim. Defendants need not show prejudice. They need not show exceptional circumstances. The absence of jurisdiction is the prejudice. The violation of due process is the injury. The lack of statutory authority is the defect that renders everything downstream unlawful. Every defendant affected by this system retains the right to challenge summary contempt sentences that were imposed without lawful jurisdiction, even years after the fact.

The filings in the Mauricio case make this point unavoidable. They demonstrate that jurisdiction is not optional. They demonstrate that statutory procedures cannot be bypassed. They demonstrate that the protections built into contempt law exist not for the convenience of courts but to prevent arbitrary detentions. They demonstrate that when those protections are ignored, the court’s actions become void and unenforceable. When applied to the wider record, these principles place hundreds of contempt entries from the last thirteen years under the same legal cloud. The court imposed punishment in cases where it had no authority to do so. And because jurisdiction cannot be created by habit, tradition, or judicial preference, these sentences cannot stand.

The implications extend far beyond any single case. The judge’s practice of labeling indirect contempt as direct did not merely violate procedural rules. It created a parallel system of punishment that contradicted the statutory structure enacted by the legislature. It replaced the due process requirements of hearings, service, counsel, and findings with a single word entered on a docket. It transformed a narrow emergency power into an all-purpose sentencing shortcut. The law does not allow this transformation. The Constitution does not allow it. And the long line of Ohio Supreme Court precedent forecloses it entirely.

As the record now stands, the court’s contempt system has been exposed. The logs reveal the pattern. The statutes define the limits. The case law confirms the violations. And the filings in the Mauricio case have forced the legal system to confront what the court had been able to avoid for more than a decade. These sentences cannot be defended on legal grounds. They cannot be legitimized through retroactive justification. They cannot be resurrected by argument or by silence. They were void from the moment they were issued.

Final Thought

For thirteen years, the Lorain Municipal Court operated a contempt system that did not resemble what the Ohio General Assembly wrote or what the Supreme Court has upheld. It functioned through habit rather than law, through repetition rather than authority, and through silence rather than transparency. The logs reveal a pattern that became so normalized inside the courthouse that almost no one questioned it, even though the governing statutes have been unchanged for decades. The consequence was not just a technical deviation from procedure but a widespread deprivation of liberty imposed without jurisdiction and without the due process protections that define the limits of judicial power.

What makes this story so disturbing is not only the scale of the violations but the way they became woven into the daily fabric of the court. This was not a single ruling or a single misinterpretation. It was a structure. It was a routine. It was a method of dealing with defendants that had replaced the legal framework entirely. And because the individuals caught in it rarely had representation, resources, or a voice, the system persisted unchallenged until one case forced the issue into the open. The Mauricio litigation did not simply expose a mistake. It exposed a system that was operating without lawful authority, and once exposed, the implications stretch far beyond one man, one case, or one courtroom.

The next part of this investigation will move from what happened to what must happen next. It will examine responsibility, remedies, and the mechanisms available to correct a decade of void sentences. It will also confront the question everyone is now asking. If a municipal court could run an unauthorized contempt pipeline for more than a decade, what other practices across the local justice system have gone unexamined, unchallenged, or undisclosed. The law provides a path forward. The record now demands it.

Legal Disclaimer

This investigation is based on publicly available records, court filings, statutory law, case law, and documents obtained through public records requests. It reflects an analysis of those materials and is offered for informational and investigative purposes only. Nothing in this publication constitutes legal advice. Readers should consult qualified legal counsel before relying on any interpretation of statutes, court rules, or judicial procedures discussed in this article. Any individuals involved in active litigation should not rely on this material as a substitute for formal legal representation. All assertions regarding judicial conduct, statutory violations, or constitutional issues are based on documented records and legal authorities, but no claim made here should be construed as a definitive finding of liability by any court or regulatory body.

Author Information

Written by Aaron Christopher Knapp, investigative journalist, public records analyst, and founder of LorainPoliticsUnplugged.com and the Unplugged with Knapp media platform. Aaron specializes in exposing government misconduct, unlawful practices, and structural failures across Lorain County’s justice system. His work combines statutory analysis, public records litigation, on-the-ground reporting, and community advocacy to bring transparency to local government operations that have long avoided scrutiny. His investigations have contributed to statewide reform discussions, multiple court challenges, and ongoing public accountability actions. Aaron’s publications appear on Substack, NewsBreak, YouTube, and his independent news site, and his reporting continues to follow the principle that sunlight remains the most reliable disinfectant in local government.

Addendum: Legal Verification and Clarifications

All legal citations and statutory references in this article have been independently verified for accuracy. The Ohio Revised Code sections cited — R.C. 2705.01, 2705.02, and 2705.03 — are quoted and summarized in accordance with their actual text and legal application. The case law relied upon, including State v. Kilbane, Cleveland v. Ramsey, City of Cincinnati v. Cincinnati District Council 51, and In re Davis, are genuine decisions issued by Ohio courts. All holdings referenced reflect the substance and context of the opinions as published.

In re Davis and Cleveland v. Ramsey are appellate-level decisions, not Ohio Supreme Court rulings, and should be read accordingly. Kilbane remains good law but applies narrowly to conduct occurring directly in the presence of the judge. Where this article uses terms like “jurisdictional defect” or “void sentence,” they refer to well-established procedural violations under Ohio law that deprive a court of authority to impose summary punishment without statutory process. These descriptions do not imply a lack of subject-matter jurisdiction in the constitutional sense.

No fictional cases, fabricated citations, or misquoted statutes appear in this publication. The facts and legal authorities presented are based on the public record and accurately reflect Ohio law as interpreted by the courts.

1 thought on “Thirteen Years of Unchecked Power: How a Municipal Judge Turned Contempt Law Into a Private Tool of Control”