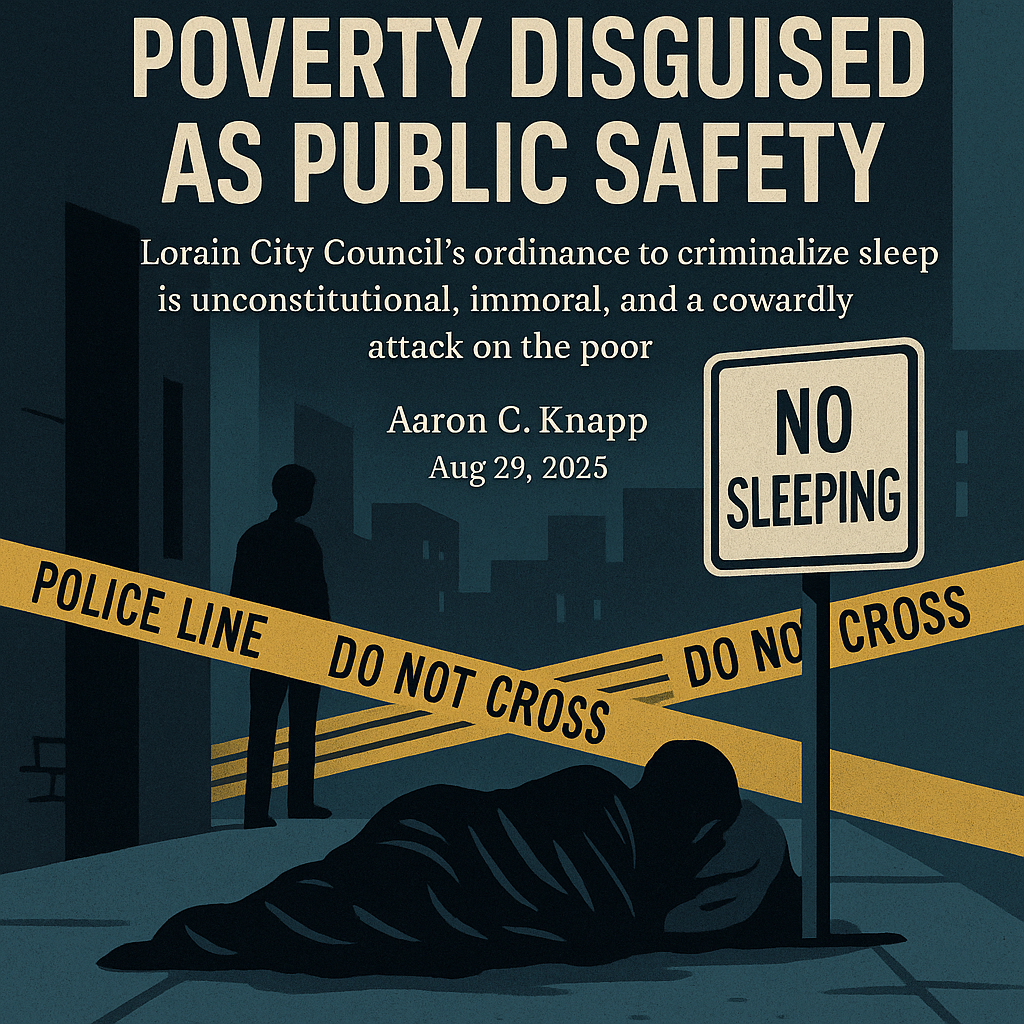

A War on Poverty Disguised as Public Safety

Lorain City Council’s ordinance to criminalize sleep is unconstitutional, immoral, and a cowardly attack on the poor

Aug 29, 2025

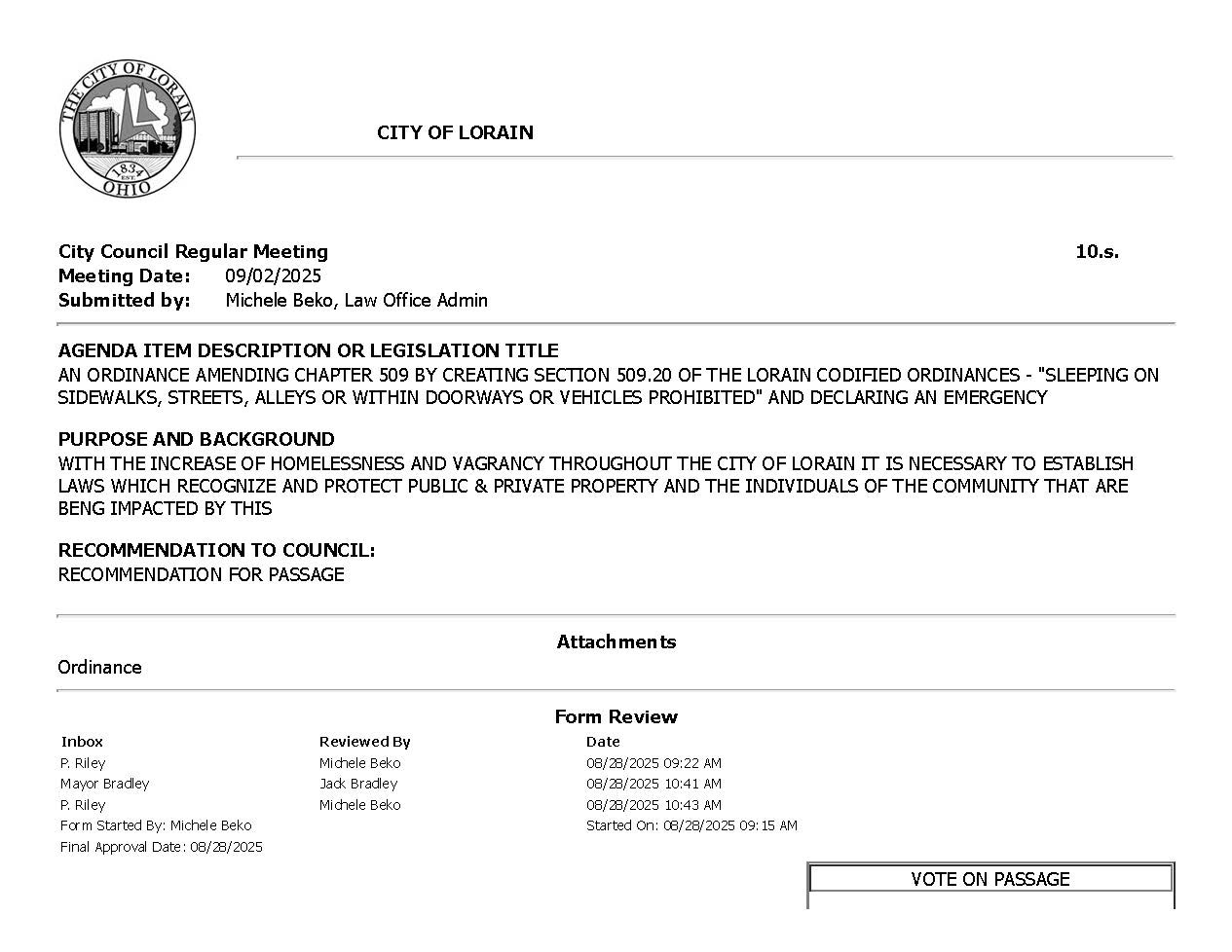

The Ordinance They Don’t Want You to Read

On September 2, Lorain City Council will put to a vote an ordinance that would, for the first time in city history, criminalize the simple act of sleep. The text of the law makes it illegal to lie down on a sidewalk, an alley, or in a doorway. It goes further: even if you find refuge inside your own car, if that car is parked on public property, you are still breaking the law. A violation carries a fourth-degree misdemeanor, which in Ohio means up to thirty days in jail and a two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar fine. The ordinance also gives police sweeping power to “immediately remove” anyone in violation. In plain English, that means displacement on sight.

“This ordinance does not solve poverty. It hides it behind handcuffs.”

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Supporters will insist this is about health and safety, pointing to public sanitation, disease, and the “integrity of public property.” But the wording itself reveals the intent: this is not about health. It is about visibility. It is about removing the poor from view, so that downtown sidewalks look cleaner, business corridors look safer, and political leaders can claim progress without actually doing the work of solving homelessness.

City Hall is fast-tracking this by declaring it an emergency. Under Ohio law, that designation allows the ordinance to take effect immediately, bypassing the thirty-day waiting period normally built into legislation. Ask yourself: what exactly is the emergency? Homelessness in Lorain did not materialize last week. Poverty has been a chronic issue here for decades.

The emergency is not public health—it is political optics.

Sleeping as a Crime

The ordinance strips human beings of their most basic dignity by redefining rest as an offense. It tells people who have nowhere else to go that even closing their eyes in public is a punishable act. If you are unhoused in Lorain, you cannot lie down on a sidewalk. You cannot seek cover in a doorway. You cannot sit in your own car to find warmth or safety if it happens to be parked on city property. Every option available to you is suddenly illegal. You are guilty simply for existing without a roof over your head.

“Sleep is not optional. Sleep is survival. Lorain wants to make survival a crime.”

Supporters of the ordinance will argue that it is “neutral,” that it applies to everyone. But laws like this are never enforced against everyone. No police officer will arrest a college student who dozes off in their car after a night out. No one will call it a crime when someone naps on a park bench during a lunch break. Enforcement will fall squarely, and only, on the backs of those who are visibly homeless.

The most chilling part of this ordinance is how casual it is. In a few lines of text, Council seeks to erase entire lives from public space. They reduce the crisis of homelessness—a crisis rooted in economics, mental health, and systemic neglect—to a misdemeanor charge. They write into law the idea that if poverty cannot be solved, it can at least be hidden.

In Lorain, this ordinance would not just ban sleeping in public. It would make the very condition of being poor indistinguishable from criminal conduct. It would tell every unhoused person in the city: you are not allowed to exist here.

Why This Won’t Survive in Court

The constitutional problems are glaring, and the courts have been clear. In Martin v. City of Boise (2018), the Ninth Circuit ruled that punishing unhoused people for sleeping outside when no shelter is available violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Sleep is not optional—it is survival. Lorain cannot prove it has enough shelter beds. That alone makes this ordinance legally vulnerable.

But Boise is only the beginning. In Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville (1972), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down vague vagrancy laws that criminalized being poor, wandering without purpose, or having “no visible means of support.” The Court called those laws unconstitutional because they targeted entire classes of people and gave police unchecked power to arrest the unwanted. Lorain’s ordinance reads like a modern-day vagrancy law dressed up in public health language.

In Pottinger v. City of Miami (1992), a federal court held that arresting homeless individuals for life-sustaining activities such as sleeping, eating, or sheltering in public violated the Constitution when no alternatives existed. Miami ended up settling the case, agreeing to stop criminalizing homelessness and to invest in services instead.

In Johnson v. City of Dallas (1994), a federal judge struck down Dallas’s ordinance criminalizing public sleeping, ruling it violated the Eighth Amendment because it punished “an unavoidable consequence of being homeless.” In Tobe v. City of Santa Ana (1995), the California Supreme Court recognized that anti-camping ordinances raised serious constitutional issues when applied to people with no alternatives.

Even Ohio has weighed in. In State v. Pennington (2007), an Ohio appellate court struck down a panhandling ban as unconstitutional, citing free speech protections. Panhandling is not the same as sleeping, but the principle is the same: you cannot criminalize the visible signs of poverty under the guise of law and order.

“Lorain is not innovating here. It is recycling laws that have already been struck down across the country.”

The Ohio Constitution provides even stronger protections than the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 1 guarantees the rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Article I, Section 11 protects the right to speak, assemble, and exist in public forums like sidewalks. When Lorain criminalizes sleeping in those spaces, it collides with both guarantees.

📚 Legal Precedents Against Criminalizing Homelessness

- Martin v. Boise (2018) – Federal court: Cities cannot punish people for sleeping outside when no shelter is available. Violates the Eighth Amendment.

- Papachristou v. Jacksonville (1972) – U.S. Supreme Court struck down vague vagrancy laws that criminalized being poor or “wandering.” Called unconstitutional.

- Pottinger v. Miami (1992) – Federal court ruled that arresting homeless people for sleeping, eating, or sheltering in public violated their rights. Led to a landmark settlement.

- Johnson v. Dallas (1994) – Federal judge struck down a sleeping ban, holding that criminalizing “an unavoidable consequence of being homeless” violated the Constitution.

- Tobe v. Santa Ana (1995) – California Supreme Court recognized constitutional issues with anti-camping ordinances when no alternatives existed.

- State v. Pennington (2007, Ohio) – Ohio appellate court struck down a panhandling ban as unconstitutional, citing free speech protections.

“From Florida to California to Ohio, the courts have been clear: you cannot make poverty a crime.”

A Guaranteed Legal Fight

If passed, this ordinance will not survive, because it runs headlong into constitutional precedent. Civil liberties organizations like the ACLU, the National Homelessness Law Center, and local legal aid societies have already fought and overturned laws just like this.

“Lorain knows this law won’t hold up in court. They’re gambling with public money and people’s lives.”

Cities that passed “sit-lie” or “anti-camping” laws have been dragged into expensive litigation. They lost, and taxpayers ended up footing the bill for legal fees, settlements, and damages—money that could have been used to fund real solutions like housing and treatment. Lorain is setting itself up for the same fate. Courts will ask a simple question: where else can these people go? If there is no answer, the ordinance collapses.

And all the while, real people will pay the price. Every citation, every arrest, every night in jail will fall on human beings whose only “crime” is being too poor to afford a bed. Council knows this. They know the law will be challenged. They know it will be struck down. Yet they are willing to gamble with people’s lives—and with public money—for the sake of looking like they took action.

That is not governance. That is politics at its most cynical.

Final Thought

As a social worker, I see every day that poverty is not a choice—it is a condition shaped by housing shortages, untreated mental health needs, addiction, trauma, and the collapse of affordable opportunity. This ordinance does nothing to heal those wounds. It does nothing to connect people to resources. It does nothing to build pathways out of homelessness. Instead, it punishes survival itself.

When government chooses handcuffs over help, fines over food, and jail cells over treatment, it abandons its duty to protect and serve the people who need it most. By criminalizing sleep, Lorain is not safeguarding health or safety. It is erasing poverty from public sight, telling its poorest residents that their very existence is unwelcome.

“This is not leadership. This is cowardice. This is unconstitutional. And it is a betrayal of Lorain’s most vulnerable.”

✍️ By Aaron C. Knapp

Licensed Social Worker (LSW) | Journalist | Candidate for Lorain City Council, Ward 6

Lorain Politics Unplugged

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article represents my opinion as a journalist, licensed social worker, and candidate for public office. It is not legal advice. Nothing in this piece should be taken as formal legal counsel. Readers should consult a qualified attorney for legal guidance.