Buying Both Sides of the Courtroom

Episode III: The Paper Trail Exposed, From Resolution to Receipt

Aug 18, 2025

By Aaron C. Knapp, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Disclaimer: This article reflects my opinion and analysis of public records. It is not legal advice, and all individuals are presumed innocent unless proven guilty in a court of law.

Previously on Episodes I and II: We traced how former County Administrator Tom Williams and his lawyer, Bill Novak, repeatedly turned Lorain County into both courtroom adversary and funding source. We saw Novak fight and lose Williams’ lawsuits all the way to the Ohio Supreme Court, and we watched the commissioners funnel millions into dead-end projects while crying budget shortfalls. This chapter picks up with the paper trail that proves, beyond spin or excuse, that Novak was paid with public funds to represent Williams personally.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In Episodes I and II, I laid out the strange dance between former County Administrator Tom Williams, his lawyer Bill Novak, and Commissioners Dave Moore and Jeff Riddell. I argued that Novak was being paid with public money to represent a man suing the County itself.

Now the receipts are here, and the paper trail is undeniable. From commissioners’ minutes to federal dockets, from Novak’s invoices to the County’s vouchers, the record shows that taxpayer dollars were diverted to cover Tom Williams’ private legal defense. This isn’t rumor, innuendo, or even my opinion, it is what the documents say, and what Ohio law calls it.

The Resolution

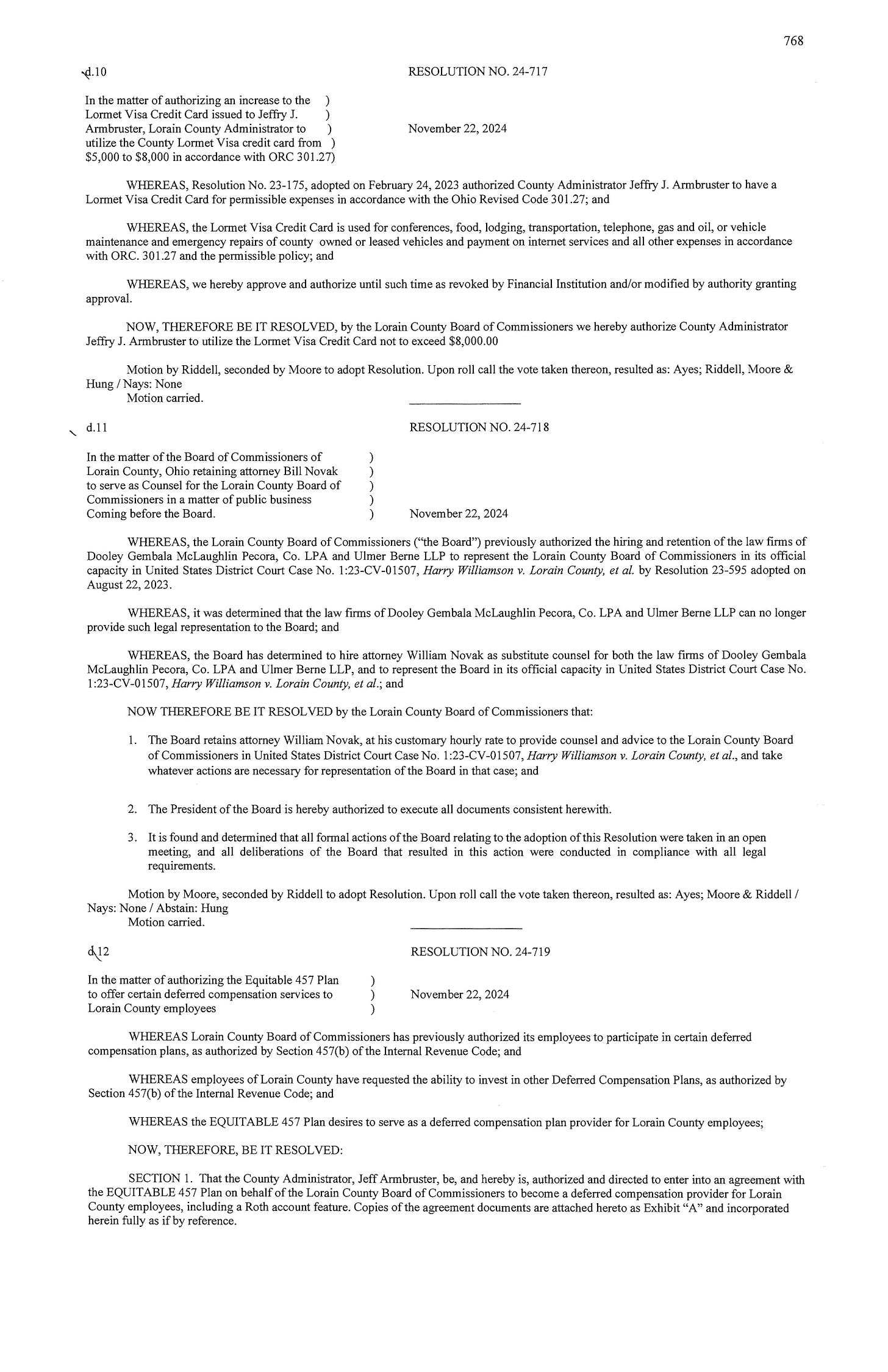

On November 22, 2024, the Lorain County Board of Commissioners passed Resolution 24-718. It states:

“The Board retains attorney William Novak, at his customary hourly rate, to provide counsel and advice to the Lorain County Board of Commissioners in United States District Court Case No. 1:23-CV-01507, Harry Williamson v. Lorain County, et al.”

On paper, Novak was hired for the Board. But under Ohio law, outside counsel for commissioners requires the consent of the common pleas court. That approval is nowhere in the record. Already, the legal footing is shaky.

Cracks Become Complicity

Less than two weeks after the Board’s resolution, on December 5, 2024, Novak entered his appearance in federal court, not for Lorain County, but for Tom Williams individually. Attorney Stephen Bosak later confirmed it in his withdrawal filing:

“On December 5, 2024, William J. Novak entered an appearance on behalf of Defendant Tom Williams as lead counsel.”

That should have ended the charade. But instead, on January 2, 2025, Novak sent Invoice #101 to the County. It said, right at the top:

“Statement of Services re: Tom Williams, 12/04/2024 – 12/31/2024.” Not “re: Lorain County.” Not “re: Board of Commissioners.” “Re: Tom Williams.”

Once that invoice hit the commissioners’ desk, there were no more excuses. They could see exactly who the work was for.

And complicity is exactly what followed.

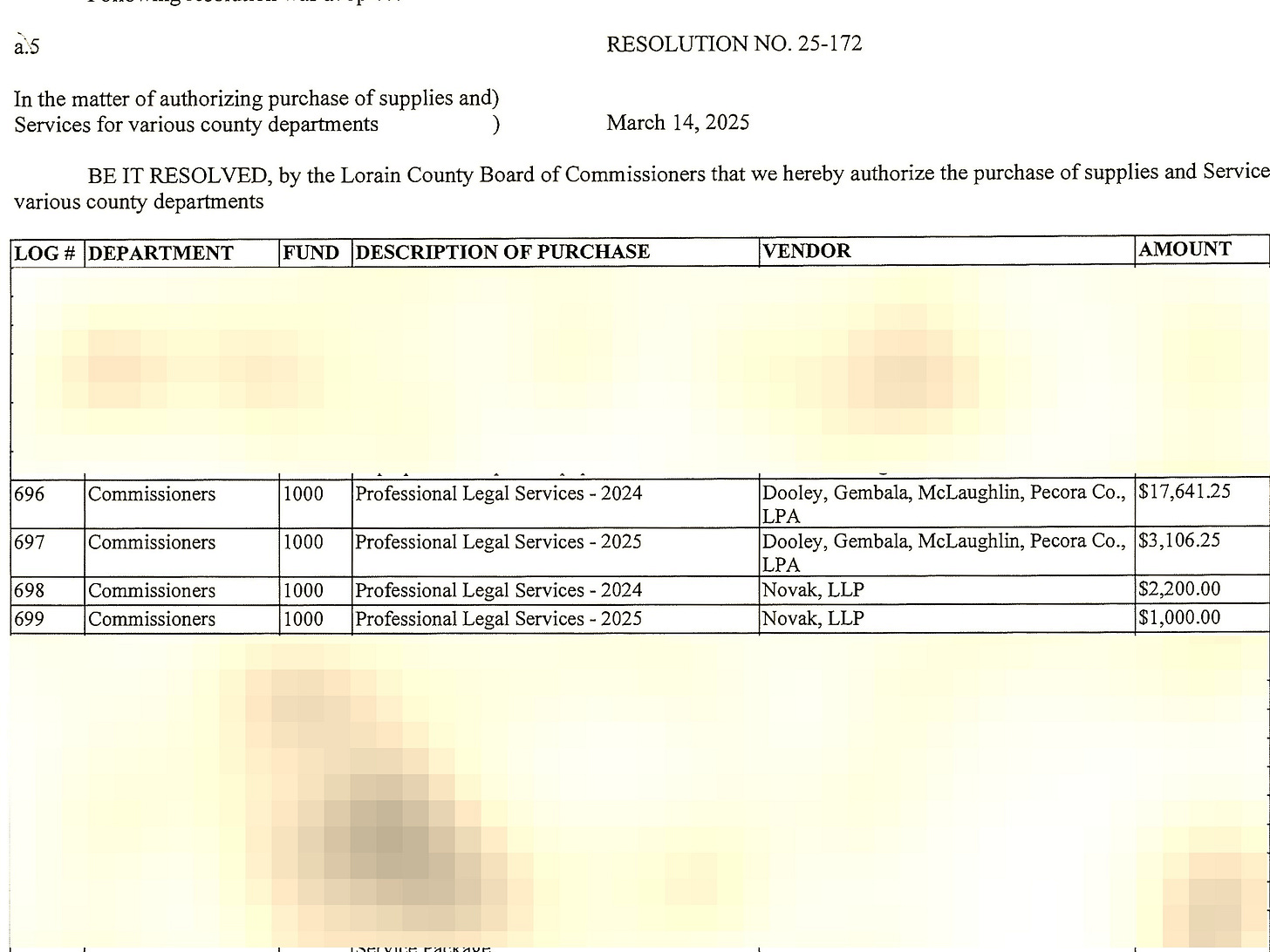

On March 14, 2025, Commissioners Moore, Riddell, and Gallagher approved Resolution 25-172.

Five days later, the County Auditor certified the voucher and cut Novak a check for $2,200 out of the General Fund.

By that point, nothing was ambiguous. The invoice spelled out the client, the docket showed Novak’s appearance for Williams, and the commissioners’ vote and the auditor’s certification meant that public officials personally approved taxpayer money to pay the private lawyer of a man suing the County.

The Withdrawal, No Excuses Left

By August 2025, the last fig leaf was gone. Bosak’s motion to withdraw confirmed it in a single sentence:

“Attorney William Novak will remain as lead counsel for Mr. Williams.”

This wasn’t a rumor whispered in the hallway. It wasn’t spin in a press release. It was a federal court filing, signed by an officer of the court .

Officer of the Court (Plain English)

Lawyers aren’t just hired guns. When they sign something in federal court, they’re acting as officers of the court — bound to honesty, ethics, and the integrity of the system itself. They can’t lie, mislead, or juggle conflicts without risking sanctions, suspension, or even disbarment.

And here’s the irony, when I was working as a Guardian ad Litem and social worker, the court fired me after McCann complained that I called myself an “officer of the court” in emails. They treated that phrase like it was radioactive. Yet now, their own hand-picked attorney — someone already conflicted six ways from Sunday — signs filings in federal court as an actual officer of the court, and nobody blinks.

At that moment, every story the commissioners had told collapsed. Novak wasn’t “helping the County.” He wasn’t a neutral advisor. He was Williams’ lawyer.

When the cracks were visible, they looked the other way. When complicity set in, they doubled down. By the time the withdrawal was filed, there were no excuses left. Just corruption in black and white.

Here’s what the law actually says, and what it means in practice:

Legal Consequences (Plain English)

Misuse of Office (R.C. 102.03)

Public officials can’t use their office to benefit themselves or their friends.

Penalty: First-degree misdemeanor, up to 6 months in jail, $1,000 fine, and removal from office.Unlawful Interest in a Public Contract (R.C. 2921.42)

Officials can’t approve contracts where their associates have an interest.

Penalty: Fourth-degree felony, 6–18 months in prison, $5,000 fine, and permanent ban from holding public office.Theft in Office (R.C. 2921.41)

Spending taxpayer money illegally, even $2,200, is theft in office.

Penalty: Third-degree felony, 9–36 months in prison, mandatory removal from office, and permanent ban from ever holding public office in Ohio.

The law is clear. What remains unclear is whether anyone will enforce it.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t an isolated blunder. Novak’s history with Williams is long and public. He represented him in the Williams v. Hung litigation, carried his appeals through the courts, and even tried to get the Ohio Supreme Court to hear the case, a door that was slammed shut without ceremony. Novak has always been Williams’ lawyer, always adverse to the County. The commissioners knew this. They still hired him. They still paid him. And they still affixed their signatures to the resolutions that made it possible.

And we’ve seen this playbook before. In Episode I, I showed how Novak and Williams had already been intertwined in failed lawsuits against Lorain County. In Episode II, we walked through the Midway Mall fiasco, where over $15 million in public funds disappeared into a redevelopment fantasy that never materialized, and touched on racketeering allegations in the Cleveland Communications case. The carousel of legal contracts for insiders, the selective enforcement of fiscal restraint, the cries of budget strain paired with sweetheart deals, it all points to the same rot.

The through-line is unmistakable: Lorain County’s political leadership treats the treasury as a piggy bank. Whether it’s millions sunk into a dead mall, racketeering accusations swirling around communications contracts, or thousands funneled to the private lawyer of a man suing the County, the pattern is the same. Public money diverted into private hands, while statutes meant to prevent it are brushed aside.

This is the bigger picture, not just Novak, not just Williams, not just one invoice. It is a governing culture that sees legal ethics as optional, conflict-of-interest laws as inconveniences, and taxpayer funds as political currency. And with each episode in this series, the picture comes into sharper focus.

The Conclusion

The timeline is not just a sequence of dates, it is a roadmap of corruption. On November 22, 2024, Novak was retained “for the Board.” On December 5, he appeared for Williams. On January 2, he billed the County “re: Tom Williams.” On March 19, the County paid that bill with public funds. By August, the federal docket confirmed that Novak was and remained Williams’ personal counsel.

That chain of events cannot be explained away. There is no benign interpretation that fits both the County’s resolutions and the court’s filings. The paper trail proves the conflict of interest. The invoices and vouchers prove the misuse of taxpayer money. The statutes spell out the crimes, and the penalties attached to them are not optional. They are mandatory.

This is not just about one lawyer’s ethics or one Board’s bad decision. It is about the erosion of public trust in the most basic safeguard of democracy, that public officials act for the public good, not for private allies. When commissioners knowingly approve payments to the personal lawyer of a man suing the County, they are not simply bending the rules. They are breaking them, and in doing so they drag Lorain County residents into the muck with them.

If this conduct is not recognized as misappropriation of funds, theft in office, and unlawful interest in a public contract, then the words in the Ohio Revised Code mean nothing. If statutes designed to prevent this exact scenario can be brushed aside, then every future commissioner in Ohio will know they can funnel money to friends, attorneys, and allies without consequence.

Lorain County taxpayers deserve more than excuses. They deserve accountability. They deserve prosecutors, auditors, and investigators who will treat these filings and invoices with the seriousness they demand. And they deserve commissioners who see themselves as stewards of public money, not as brokers in backroom deals.

The documents are plain. The money trail is plain. The law is plain. What remains to be seen is whether enforcement will be. Because if no one acts now, the citizens of Lorain County won’t just be footing the bill for this scandal, they will be paying the price for every future abuse it encourages.

This was the paper trail they couldn’t hide. What comes next may be the evidence they can’t explain away.

Disclaimer:

The information presented in this article is for informational and educational purposes only. It reflects the author’s analysis and opinions based on publicly available records and documents provided. Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal advice or a definitive statement of law. Readers should not act or refrain from acting on the basis of this content without seeking appropriate legal or professional counsel. The author makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information and accepts no liability for any loss or damages arising from its use. All individuals mentioned are presumed innocent unless and until proven otherwise in a court of law.