Demo or Favor? Lorain’s Fast-Tracked Teardown Next to the Council President’s Club Raises Red Flags

A crumbling South Lorain building is finally coming down—but critics say its proximity to the Mexican Mutual Society and the political power of Council President Joel Arredondo make the timing suspect

Jun 18, 2025

By Aaron Knapp Investigative Journalist, Social Worker, & Advocate

A Building Falls, Questions Rise

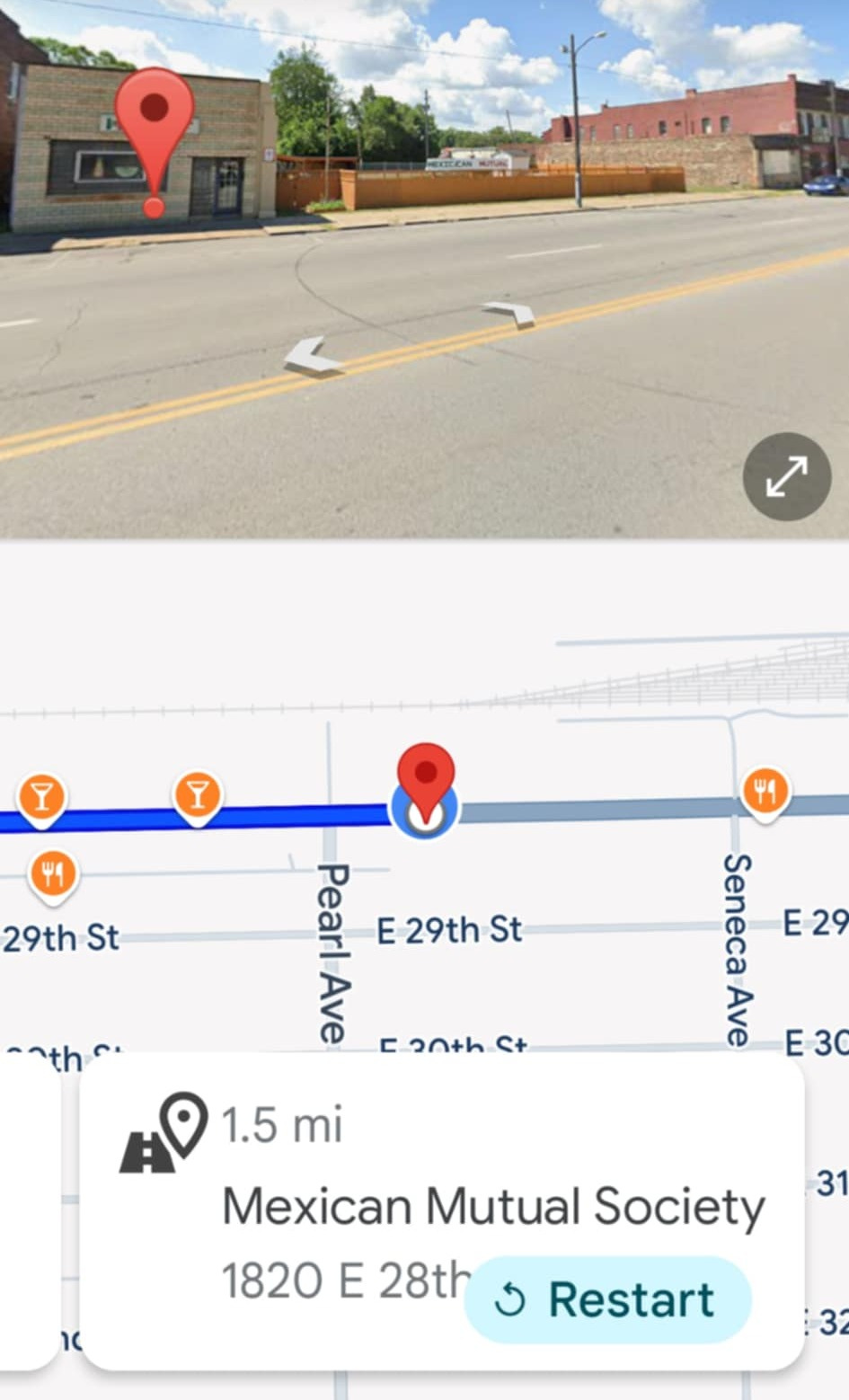

On the surface, it looks like a win for the neighborhood: a long-blighted commercial structure at 1808 East 28th Street is finally coming down. Councilman Angel Arroyo Jr. proudly posted the announcement on Facebook: the City of Lorain has approved the demolition and will knock the building down within two weeks. But beneath the surface of that celebratory message lies a deeper and more politically charged question: why this building, and why now? Lorain is littered with hundreds of dilapidated houses and commercial eyesores that have lingered for years. Yet this property—connected to a prominent social club with ties to Council President Joel Arredondo—is being expedited for demolition, raising legitimate concerns of selective enforcement, favoritism, and political self-dealing.

The building at 1808 E. 28th isn’t just any property. It shares a wall—or at least sits inches away from—the Mexican Mutual Society at 1820 E. 28th, a landmark Hispanic community club where Arredondo serves as president. This proximity means that the Mutual stands to benefit directly from the removal of the blighted building. While the City says it’s acting out of concern for public safety, critics wonder aloud: is this simply good governance or a quiet favor for political allies? The timeline for the demo—approved and scheduled in a matter of weeks—has only added fuel to the speculation.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I’ve spent the most of today reviewing demolition records, Lorain County property ownership data, and council ordinances, and interviewing my source’s who’ve long waited for their own neighborhood nuisances to be addressed. The findings reveal a pattern: while demolitions elsewhere get bogged down in red tape, this one raced to the front of the line. And while there’s no smoking gun—no email or council motion proving a favor was called in—there is something arguably worse: the unmistakable appearance of privilege. In politics, appearances matter. And in this case, the optics are bad.

The Property: 1808 E. 28th – Eyesore or Emergency?

Let’s be clear: 1808 E. 28th Street is not a hidden gem. It’s a crumbling 1-story commercial structure, most recently listed for sale in 2024 for a meager $12,999. Photos from real estate sites and councilmember posts show visible roof damage, boarded windows, and a building that has clearly outlived its use. According to city ordinance, buildings that are more than 50% deteriorated and pose a public hazard can be demolished by the City. But the City rarely moves this fast. Most demolitions, even after being declared dangerous, sit on the books for months—sometimes years—before the wrecking crew shows up.

So what makes this case different? According to Ward 6 Councilman Angel Arroyo Jr., it was an emergency order signed off by the Chief Building Official. That means it bypassed the normal route through the Demolition Board of Appeals, saving months of public hearings, contractor bidding, and environmental reviews. Emergency orders are legal—but they’re usually reserved for buildings on the verge of collapse or those already damaged by fire. The city’s rapid action here suggests a level of urgency not publicly explained. And given the building’s long-standing vacancy, one has to ask: what changed now?

The building’s close proximity to the Mexican Mutual Society—perhaps inches away—raises further questions. Could a structural inspection have determined the building was threatening its neighbor? Maybe. But why now, after it stood derelict for years? Was it really unsafe overnight, or simply politically inconvenient? The pattern is familiar to anyone who’s watched city governments long enough: action where it benefits the powerful, delays where it doesn’t. And in this case, that line may have been crossed.

The Neighbor: The Mexican Mutual and the Council President

The Mexican Mutual Society isn’t just another neighborhood club. Founded nearly a century ago, it’s a cultural institution in Lorain’s Hispanic community. And its current president is none other than Lorain City Council President Joel Arredondo. This dual role—as both elected official and adjacent property stakeholder—makes the demolition of 1808 E. 28th a matter of public ethics as much as public safety.

Arredondo has not made any public statements about the demolition, nor has there been any council vote linking him directly to the process. But silence doesn’t erase suspicion. When a powerful official stands to gain from the city’s action—even if indirectly—it casts a long shadow. The Mutual will benefit from the demolition. Whether it uses the space for parking, security, or visual appeal, it will clearly be in a better position than before. And given the club’s prominence, any benefit to it has political value.

This isn’t to say Arredondo did anything illegal. There’s no proof of backroom deals or official misconduct. But the appearance of influence—of city resources deployed in a way that ultimately helps a sitting council president—is something the public has every right to scrutinize. Especially when other neighborhoods have been waiting years for similar action. The public deserves to know: was this building just that dangerous, or just that politically inconvenient?

The Records: Recent Demolitions Show a Slower Pattern

To understand how unusual the 1808 E. 28th demolition is, you have to look at what’s happened elsewhere in the city. Over the past two years, the City of Lorain has approved dozens of demolitions. Many were routine: fire-damaged homes, abandoned duplexes, or neglected commercial buildings. In nearly every case, the process took months. In some, it took over a year.

Take 1756 Oakdale, a dilapidated duplex owned by an out-of-state LLC. It was declared unsafe in early 2024 but still stood for months before the City took action. Or 958 Washington Ave., whose owner never even showed up to their Demolition Board hearing. Still, the process dragged. Even the infamous El Patio building on Grove Ave., known for its massive size and high-profile vacancy, wasn’t torn down until months after its approval.

In most cases, the City relied on federal grants or county land bank partnerships to fund the work. These funding mechanisms come with strings attached—environmental reviews, asbestos testing, competitive bidding—which slow things down. So when 1808 E. 28th skips all that and gets bulldozed in under a month, people notice. Especially those still living next to hazard homes that have been on the list for years.

The Process: Emergency Powers or Political Expediency?

City ordinance allows for emergency demolition when a structure is deemed an imminent public hazard. In theory, that makes sense: if a roof is caving in or a wall threatens to collapse, the City shouldn’t have to wait through weeks of hearings. But emergency powers are supposed to be used sparingly. In most of the city’s recent demolitions, even dangerous structures were processed through the usual appeals board.

So what triggered the emergency declaration for 1808 E. 28th? There’s no public record of a building inspection, no fire report, no complaint from a neighboring resident or business—at least none released to the public. That absence of documentation is troubling. Because if this wasn’t truly an emergency, then the City bent its own rules to benefit a politically connected party. That’s not just poor governance—it’s a red flag. (as of the writing of this article no evidence could be found to signify these actions were ever taken)

Transparency matters. The City should be able to provide records of the building’s condition, the decision to fast-track, and any communication from elected officials. If the decision was made purely on safety grounds, great—show us. But so far, there’s been no such transparency. And in the absence of answers, the public is left to connect the dots. And those dots don’t look good.

The Timeline: When Speed Becomes Suspicion

City demolitions are rarely swift. They typically follow a long paper trail of code violation notices, hearings, cost estimates, environmental checks, and eventual scheduling based on funding availability. That’s what makes the 1808 E. 28th case so unusual. The timeline from city notice to approved demolition—followed by a public announcement of imminent teardown—all unfolded in a matter of weeks. Compare that to the standard timeline for demo projects in Lorain, which can drag on for six months to two years.

Councilman Arroyo’s announcement makes it clear that the demolition is moving under an emergency declaration. But when emergency orders are invoked without a precipitating event—such as a fire, structural collapse, or police/fire report—the public is right to question why. What made this building an emergency now, in June 2025, when it has sat crumbling for a decade? Where is the documentation of the tipping point? If city officials have a structural report or safety analysis, they should release it.

The truth is, demolition “speed” in Lorain often depends more on politics than hazard. Residents in other wards have waited years to get even modestly dangerous homes removed. Yet here, with a structure connected to the Council President’s longtime community club, the timeline shortens dramatically. The process was treated as urgent, but the urgency wasn’t publicly explained. It’s not hard to see why people believe it may have been fast-tracked—not because it became more dangerous overnight, but because someone wanted it gone.

The difference between a one-year wait and a two-week turnaround is not just logistics—it’s priority. And that priority often reflects who stands to benefit. If that benefit happens to flow directly to a politically connected nonprofit where the Council President is the leader, then the public has every reason to press for transparency. Because this demolition may not just be an outlier—it may be a template for how connected buildings get cleaned up faster while everyone else is left to wait.

The Council Connection: When Proximity Isn’t Neutral

Proximity matters. And in Lorain, proximity to power often changes outcomes. Council President Joel Arredondo is not just an at-large elected official; he’s also the president of the Mexican Mutual Society, the building directly adjacent to the condemned 1808 E. 28th. When the city acts on a property that borders a politically powerful figure’s interest, the line between governance and favoritism becomes hard to distinguish—even if technically no rules are broken.

There’s no evidence, as of this writing, that Arredondo filed any formal request to prioritize the demolition.

But politics often works in subtler ways. A quiet conversation, a heads-up email, a suggestion in a back hallway—these are all tools of influence that leave no paper trail. And when a council president stands to benefit directly from the clearing of an eyesore, even indirect signals can carry weight. The very fact that Arredondo leads a property adjacent to 1808 makes it impossible for the public to view the demolition as neutral.

What further complicates this situation is the dual role Arredondo occupies. As Council President, he has oversight over budgetary decisions, departmental accountability, and inter-agency coordination. He doesn’t have to overtly direct staff to exert influence—the mere knowledge of who benefits can subtly steer decisions. And in a city like Lorain, where personal relationships often overlap with political roles, these entanglements should not be ignored.

This isn’t a call to smear Arredondo. It’s a call for clarity. If the City acted in the best interest of public safety, then prove it. Release the inspection reports. Publish the internal timeline. Show that the demolition was prioritized on merit, not on adjacency to political leadership. Because without that transparency, every resident in Lorain has a reason to wonder whether their neighborhood would get the same treatment.

The bigger issue isn’t what happened to 1808 E. 28th—it’s what didn’t happen elsewhere. If this building went down because of who it touched, what about the hundreds of other buildings that touch no one with political pull? The fairness of city enforcement depends on the impartiality of its process. Right now, the process looks partial—and Arredondo’s proximity makes it impossible to ignore.

The Community Response: Favoritism or Fairness?

Reaction to the demolition announcement has sparked concern in at least one corner of the community. A local resident reached out to the author and questioned the timing of the demolition, its proximity to the Mexican Mutual Society, and whether political connections played a role in fast-tracking the process (The Post is on Angel Arroyo’s Campaign Page and he has me blocked even though he posts government information there, maybe if he took the Sunshine Law course he would know thats a no-go…but I digress). While not a groundswell of backlash, the individual reporting it to me captures a familiar sentiment in Lorain: that who you know often matters more than what’s falling down around you.

Community skepticism is not without precedent. Lorain has a long and complicated history with selective enforcement—from uneven code crackdowns to politically convenient investments in public works. People remember when other structures, arguably worse than 1808 E. 28th, were allowed to rot for years. They remember being told that there were no funds, no crews, no capacity to act. And they remember being promised that blight removal would follow a fair and transparent process. That’s why this case feels different—and not in a good way.

What troubles observers is not the demolition itself, but the pattern it could represent. If the City of Lorain is in the business of clearing eyesores only when politically advantageous, then every future decision is now suspect. The public has a right to ask whether resources are being allocated equitably—and whether neighborhoods without council allies are being left behind. That’s not cynicism; that’s civic vigilance.

Residents in Lorain deserve to live in neighborhoods free from collapsing structures and city neglect. But they also deserve a government that plays by the same rules, no matter the address or political affiliation. When a city moves with urgency for one block but inertia for another, people notice. And when that block happens to sit beside a council president’s property, people talk. That’s not paranoia; that’s democracy in action. And when that block happens to sit beside a council president’s property, people talk. That’s not paranoia; that’s democracy in action.

The Double Standard: Who Gets Help, Who Gets Ignored?

Walk through other parts of Lorain and you’ll find buildings that make 1808 E. 28th look like a fixer-upper. There are houses with caved-in roofs, porches hanging by a nail, and whole commercial corridors where vacancy and vandalism are the rule, not the exception. And yet, these properties remain standing. Some have been on the city’s radar for years. Residents in those areas, many of whom lack the proximity to political influence, are still waiting.

That’s where the double standard becomes obvious. It’s not that 1808 didn’t deserve to come down—it’s that it came down so fast.

The same urgency is rarely extended to less visible corners of the city. Where was the emergency order for the fire-damaged duplex on Oakdale? Where was the fast-tracking for the boarded-up triplex on Grove? If public safety is truly the measure, then many other buildings should have beaten 1808 to the bulldozer.

It’s this selective urgency that fuels distrust. And it’s why public faith in city processes erodes even when the end result is technically defensible. Because if demolition timelines vary based on who’s watching—or worse, who’s standing next door—then the whole system becomes a matter of favoritism, not fairness. Cities don’t just need rules. They need consistency.

And the pattern here is consistent—but not in the right way. Buildings that touch political interests get attention. Those that don’t are left to rot. It may not be a formal policy, but it’s a lived reality for too many residents. If your street lacks a councilman’s clubhouse or a family connection to city hall, you learn to live with blight. You learn that the rules don’t apply evenly.

To be clear, this isn’t just a Lorain problem. Cities across Ohio face similar struggles with enforcement equity, funding gaps, and community trust. But Lorain can choose to be better. It can lead with transparency, follow its own timelines, and apply its standards universally. What it cannot do—at least not without consequence—is pretend that no one notices the disparity.

When residents see crumbling buildings linger year after year in their own neighborhoods while one next to a council president gets bulldozed within days, the message is clear: power speeds things up. And that message, left unchallenged, does lasting harm. Because once people believe the city doesn’t treat them equally, they stop expecting it to. And that apathy is far more dangerous than any decaying building.

Final Thought: The Danger of Appearances

Sometimes the problem isn’t what’s done—it’s how it looks. The demolition of 1808 E. 28th may well have been legal, justified, and overdue. But its timing, its speed, and its proximity to a council president’s property all raise valid questions about fairness, access, and influence. Even if no favors were explicitly asked or granted, the fact that so many residents instantly suspected one says something profound about public trust in Lorain.

That suspicion is a problem all its own. Cities function best when residents believe their government acts impartially. When demolitions are carried out based on risk, not relationships. When eyesores are addressed according to need, not neighborhood rank. And when leadership goes out of its way not only to avoid impropriety, but to avoid the appearance of it. Because appearance matters. In fact, it’s everything.

If Lorain wants to restore public faith, it must prove that access to power doesn’t determine access to services. That every unsafe structure gets the same urgency, regardless of whose backyard it’s in. That neighborhoods without clout matter just as much as those that have it. And that elected officials won’t quietly benefit from the machine they were elected to manage.

This story isn’t over. The demolition will happen. But the questions will remain. Who’s next in line? Who isn’t? And how will the public know whether the next teardown is about safety—or politics? The people of Lorain deserve answers. And if they don’t get them, they deserve to keep asking.

Legal Disclosure

This article represents the informed opinion of the author, based on publicly available records, property data, and firsthand documentation at the time of publication. All individuals and public officials are presumed innocent of any wrongdoing unless proven otherwise. No portion of this report should be interpreted as a legal accusation, and no allegations of criminal activity are made. Readers are encouraged to review official records and seek out additional sources to form their own conclusions.