The Case They Couldn’t Prove: How Elliut Pallens Beat the City of Lorain

Four Charges, One Trial, Zero Convictions — A Jury Verdict That Raises Bigger Questions

May 21, 2025

By Aaron Knapp, Investigative Reporter

Introduction

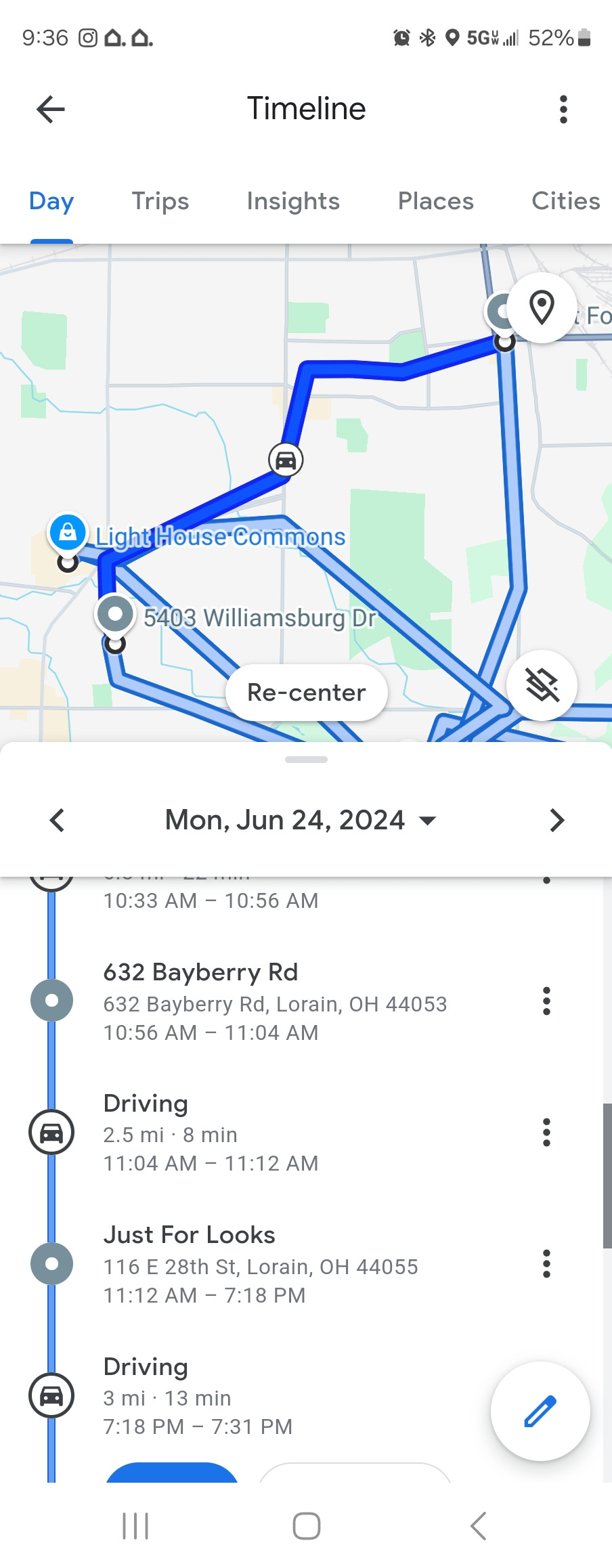

The criminal case against Elliut Pallens began not with an officer’s firsthand account or a cruiser being struck—but with a civilian flagging down a patrol officer after the fact. The charges that followed were based entirely on the word of one individual, Ashley Schilla, who claimed Pallens had hit her car and fled. There were no police witnesses, no immediate photos, and no damage documentation at the time. Still, the City of Lorain pursued Pallens as if the allegations had been observed by law enforcement. What followed was nearly a year of legal maneuvering, public pressure, surveillance, and an eventual jury trial—where a panel of citizens saw the truth and cleared him of all charges.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I. The Charges That Followed a Civilian’s Word

Pallens was charged with four misdemeanors under Lorain’s city ordinances: failure to comply with a police order, reckless operation, failure to stop after an accident, and a marked lanes violation. These weren’t minor infractions, at least not in the eyes of the prosecutor’s office. They were stacked in such a way as to suggest that Pallens had recklessly struck a vehicle—allegedly belonging to Ashley Schilla—ignored the resulting commotion, and then fled, disrespecting the responding officer who had been waved down by Schilla herself.

Each charge carried not just a potential fine or jail time, but the stigma that comes with criminal allegations. The reckless operation count could have affected his driving privileges and insurance. The failure to comply charge, often associated with fleeing from police, carried the implication that Pallens had acted defiantly when stopped. In reality, the officer never witnessed the alleged event—and didn’t initiate a stop based on direct observation, but on hearsay.

Public records now confirm that Officer Nicholas Gerace was not the alleged victim but was simply flagged down by Schilla. The city nonetheless charged Pallens as if Gerace had witnessed the alleged hit-skip and constructed a narrative implying officer endangerment. This misrepresentation gave weight to the charges and likely discouraged internal scrutiny.

Documents also show that Schilla was the only civilian subpoenaed to testify and was repeatedly asked by the city to “bring proof of damages to court.” This detail is critical—it shows that no damage had been documented by law enforcement at the time of the accusation. There were no photos of her vehicle in the original report and no official inspection of Pallens’s car.

Gerace became the primary law enforcement witness—not because he observed anything—but because he responded after Schilla flagged him down. His role was purely reactive. That distinction matters because it reorients the entire prosecution from “officer-driven charges” to “third-party hearsay enforcement.”

Despite this, the city treated the charges as though they came with firsthand credibility. Officer Gerace’s cruiser was not involved, and he had no camera footage confirming the incident. Yet the city pressed forward with citations that required assumptions about Pallens’s driving, his intent, and his conduct—all based on what a single civilian told police.

That decision became even more questionable as the case unfolded. The defense presented workplace logs, Google location data, and even Vivint camera footage suggesting that Pallens never left his barbershop during the timeframe of the alleged hit. Still, the city declined to drop the charges.

The marked lanes citation was especially dubious. It relied on the idea that Pallens had swerved into Schilla’s lane—a fact no police officer observed and which Schilla herself never documented with evidence. Without video, photos, or neutral witnesses, this became a battle of narratives. And in court, that’s not supposed to be enough.

Ultimately, these charges weren’t grounded in evidence—they were grounded in momentum. Once Schilla made her claim, the city built an entire prosecutorial apparatus around it. And because an officer happened to be nearby when she complained, the city gave the story the full weight of law enforcement authority. It took a jury to unravel it.

II. The Pressure to Plead

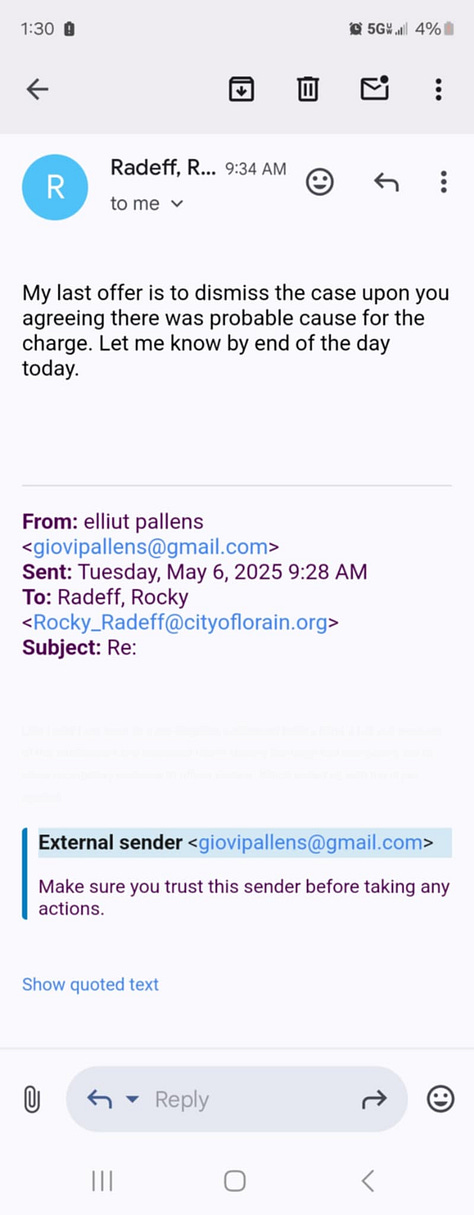

Even before the jury was sworn in, the City of Lorain made repeated attempts to sidestep trial altogether—by offering to dismiss the charges, but only if Elliut Pallens admitted that there had been probable cause to bring them. It was a backdoor plea deal, one that would allow the city to save face without ever having to prove its case. Pallens refused.

In multiple emails shared directly with this reporter, Assistant Law Director Rocky Radeff made the offer clear: “The offer is dismiss with you admitting to probable cause for the charge.” The timing of these emails—sent days before trial—suggested a last-ditch attempt to secure a favorable exit without risking the scrutiny of a jury.

This wasn’t a case of dropping charges because evidence failed to materialize. It was an effort to rewrite the official record. An admission of probable cause would create the appearance of legitimacy, shielding the city from future civil claims or professional consequences. It would turn a baseless case into a retroactive justification.

Radeff’s insistence on that language, despite mounting evidence that the timeline didn’t hold and no physical damage was ever documented, casts a long shadow. According to Rule 3.8(a) of the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct: “The prosecutor in a criminal case shall refrain from prosecuting a charge that the prosecutor knows is not supported by probable cause.”

As an experienced prosecutor with years of plea negotiations on behalf of the City of Lorain, Radeff should have been well aware of this ethical rule. That he continued to press for an admission anyway suggests either a willful disregard of the standard or a calculated gamble that the defendant would fold under pressure. One can’t help but wonder: how many other defendants in Lorain have taken that same deal?

The city’s aggressive posture wasn’t subtle. The emails carried firm deadlines and implied consequences if the offer was rejected. “Please approve or deny the offer by the end of the day,” one read. Pallens answered simply, “Deny. There was no probable cause.”

It is to his credit—and to the integrity of the trial process—that he stood firm. For many defendants, the temptation to accept a dismissal, even with strings attached, is hard to resist. The fear of losing at trial, of facing court costs, or of being smeared publicly, often outweighs principle. Pallens took the risk. And in doing so, he exposed just how hollow the state’s case really was.

This incident also highlights a broader concern: that plea bargaining, as practiced, often operates as a tool of coercion. When evidence is weak, the pressure to admit guilt—or at least concede justification—becomes a way for prosecutors to extract compliance without accountability.

Had Pallens agreed to the terms, the case would have vanished from the docket. No jury would have heard his evidence. No judge would have ruled on the merits. And the city would have walked away with a quiet win. Instead, the record now reflects something very different: not guilty on all counts.

That outcome didn’t just vindicate one man. It revealed a deeper truth about the way some prosecutors operate—not to uphold justice, but to manage outcomes. And in this case, they failed at both.

III. The Timeline That Didn’t Add Up

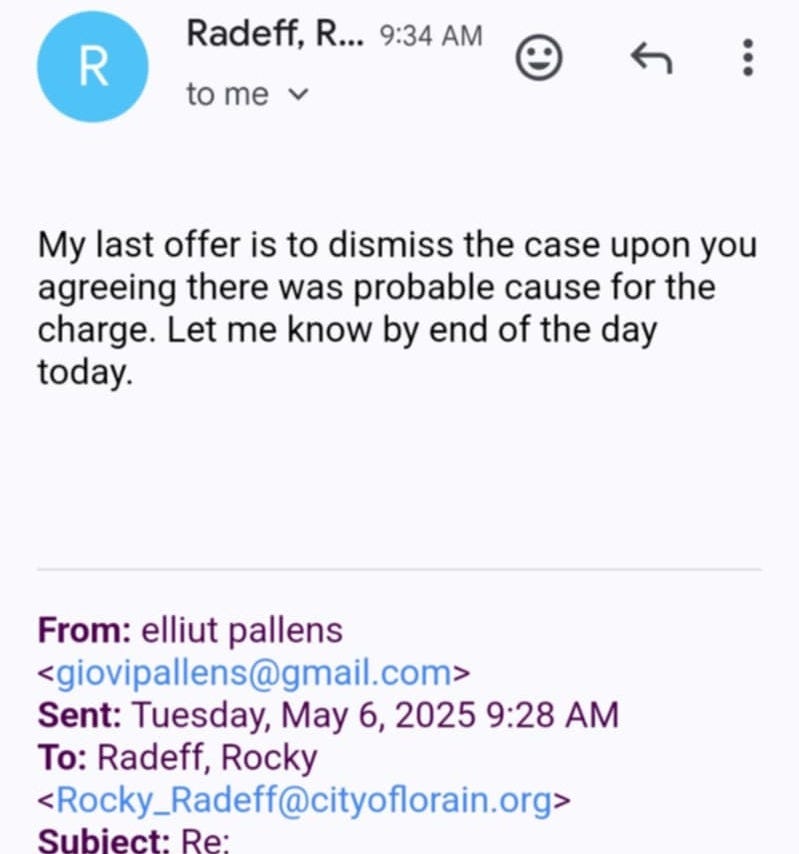

Central to the prosecution’s theory was the idea that Elliut Pallens had fled the scene after colliding with Ashley Schilla’s vehicle on June 24, 2024. The alleged incident, they claimed, happened near 23rd Street around 4:00 p.m. But Pallens’s own records — pulled from Google location history and his workplace’s schedule — placed him at the Just For Looks barbershop on East 28th Street throughout the entire day, including the time of the supposed collision.

Vivint camera footage from the business, time-stamped metadata, and GPS records showed that Pallens never left the premises. He had no reason to. It was a busy workday. Despite this, Officer Gerace — flagged down by Schilla — wrote four traffic citations as if he had personally witnessed the incident. He had not.

The city never produced dashcam footage, body cam recordings, or photos of the damage Schilla allegedly sustained. No immediate damage assessment was conducted. And despite issuing citations with legal consequences, Gerace made no attempt to verify Pallens’s identity through an interview, inspection, or follow-up investigation.

Public records requests submitted by Pallens — including one asking for any video of Officer Gerace following Schilla after the alleged incident — went unanswered. But subpoena documents reviewed by this reporter confirm the city requested that Schilla “bring proof of damages to court.” This request, issued months after the citation, suggests the city had no photos or verified documentation when charges were filed.

Meanwhile, defense materials were consistent and meticulously documented. Google location data provided precise coordinates placing Pallens at work. Phone screenshots matched Vivint system timecodes. Witnesses could corroborate his presence. The prosecution, by contrast, relied entirely on a narrative: Schilla said it happened, and Gerace wrote the tickets.

Even more puzzling, the city never sought to reconcile the inconsistencies. They made no effort to amend the timeline, introduce physical evidence, or challenge the defense’s metadata. They simply continued forward with a case that had no anchor in material fact.

In court, this disconnect became obvious. The prosecution had no answer for the timeline presented by the defense. Their lack of video, third-party witnesses, or even photographic evidence spoke louder than any witness could.

And then came the ultimate contradiction: if this were truly a hit-and-run, why didn’t the officer who wrote the ticket immediately stop or pursue Pallens? Why wasn’t there an arrest, a confrontation, or even a phone call? Why was it left to a civilian to complain, and then months later, to supply evidence?

What emerged at trial was a stark contrast between assumption and accountability. The state’s timeline didn’t just fail to add up — it never existed to begin with. The jury saw through it. And when they returned their verdict, they didn’t just clear Pallens of wrongdoing. They exposed the city’s failure to investigate before it prosecuted.

IV. Ethical Concerns: Prosecutorial Conduct Under Scrutiny

As troubling as the lack of evidence was, the conduct of the City of Lorain’s prosecution team raised even deeper concerns. With no direct witness, no physical damage documentation, and no police officer having seen the alleged event, the city still pursued criminal charges against Elliut Pallens. And when those charges began to crumble under scrutiny, prosecutors attempted to negotiate an escape—one that would shield them from accountability.

Pallens was offered a dismissal on the condition that he admit probable cause had existed for the citations. This wasn’t about guilt or innocence—it was about narrative control. In emails reviewed by this reporter, Assistant Law Director Rocky Radeff repeatedly conditioned dismissal on that single admission. One message read: “The offer is dismiss with you admitting to probable cause for the charge.”

According to Rule 3.8(a) of the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct, prosecutors must not pursue charges they know lack probable cause. “The prosecutor in a criminal case shall refrain from prosecuting a charge that the prosecutor knows is not supported by probable cause.” Yet here, even as the case unraveled in discovery, Radeff insisted on extracting an admission of legitimacy from a defendant the city had failed to prove had done anything wrong.

This raises a sobering question: if the evidence was truly lacking, why was the case not dismissed outright? Why was the city attempting to coerce a concession that could later be used to defend against civil liability or bar a wrongful prosecution claim?

Radeff is not a novice prosecutor. His long tenure with the city includes dozens, if not hundreds, of plea negotiations and municipal court appearances. That he would continue to press for an admission of probable cause under these circumstances suggests either a willful disregard for ethical obligations or a systemic pattern of plea bargaining used as legal insulation rather than justice.

Legal observers have criticized this tactic as a form of coercive plea practice—common in misdemeanor courts where overworked public defenders and overwhelmed defendants are pressured to accept deals to avoid prolonged legal battles. But in Pallens’s case, it became a test of principle. He refused. And it cost him months of stress, time, and resources.

This is not just an anecdote—it’s a pattern. The city’s reliance on conditional dismissals, unsupported by tangible evidence, undermines the foundations of justice. It creates a chilling effect where individuals are punished not based on proven wrongdoing, but for asserting their right to a trial.

It also sets a dangerous precedent: that the appearance of authority, rather than factual grounding, is enough to bring criminal charges and justify them after the fact through technical legal concessions.

Fortunately for Pallens, the jury saw through it. But others may not be so lucky—or so persistent. The ethical breach here lies not just in the prosecution’s decision to proceed, but in their refusal to retreat once the case showed cracks. That refusal, more than any single charge, is what should concern every resident of Lorain.

V. The Alibi the City Refused to Acknowledge

Despite being informed of Pallens’s alibi months before trial, the City of Lorain made no serious effort to evaluate, investigate, or contest the evidence he provided. While a formal Notice of Alibi was not filed with the court, Assistant Law Director Rocky Radeff and the city prosecutor’s office were repeatedly notified that Pallens was at work at the time of the alleged incident—supported by Google Maps location tracking, business security footage, phone records, and witness testimony.

The evidence was extensive and consistent. GPS logs from Pallens’s phone placed him inside Just For Looks barbershop throughout the day on June 24, 2024. Vivint security footage from the front and interior of the business showed him serving clients. Time-stamped screenshots from his device matched his physical presence on the property. Despite receiving this material, the prosecution offered no rebuttal. They simply ignored it.

In more than one instance, Pallens emailed the city requesting that they review the footage and location data. He even offered to bring in witnesses who could testify to his presence at the shop during the time of the alleged hit-skip. These requests went unanswered. The prosecution filed no motion to exclude the evidence, no counter-expert testimony, and made no attempt to obtain their own metadata.

Even more telling, the city never asked Schilla—the complainant—to provide timestamps, third-party corroboration, or damage reports from the time of the incident. Her claim remained unverified until trial. The only documentation she was asked to bring was listed in a subpoena dated months later: “Please bring proof of damages to court.”

This failure to investigate a known alibi isn’t just procedural negligence—it reflects a deliberate strategy. Prosecutors hoped to keep the jury focused on allegations, not facts. By ignoring the digital evidence, they avoided having to explain away a timeline that directly contradicted their theory of the case.

It also speaks to how little interest the city had in actual fact-finding. While the defense scrambled to document and preserve location data, the city failed to preserve or produce dispatch logs, officer camera footage, or even basic reports that could have clarified the timeline. It was not just a case built on weak evidence—it was a case built in spite of strong exonerating evidence.

This alibi evidence became central to the jury’s understanding of the case. When presented with clear documentation of where Pallens was, and for how long, the prosecution had no response. Their silence was as damning as any cross-examination. Jurors were left to weigh hard data against a verbal claim.

In most cases, such an alibi would warrant a dismissal or, at minimum, a reassessment of the charges. But here, the city refused to budge. They didn’t want a fair result—they wanted a procedural win, even if it meant disregarding a well-supported alibi from the very start.

That the jury reached four not guilty verdicts speaks volumes. It suggests that in the absence of police witnesses, physical evidence, or a coherent timeline, the only thing the state had going for it was stubbornness. In refusing to engage with the alibi, the city revealed its priorities—and they had nothing to do with truth.

VI. Surveillance as Pressure: A Police Presence with No Purpose

As the case against Pallens progressed, a new layer of concern emerged—not from the court, but from the curb. According to time-stamped photos and firsthand observations, marked Lorain Police cruisers began parking for extended periods outside Just For Looks, the barbershop where Pallens worked. These vehicles weren’t responding to 911 calls or engaging with local businesses. They were parked, facing the building, often idling with no action taken.

Pallens, who had already been accused based solely on hearsay, began to document what he believed was a coordinated act of low-grade intimidation. Photos taken on multiple days show cruisers parked in the same location across from the business. One image shows an officer visibly facing the window where Pallens stood working. There is no indication from dispatch records or any call logs that the officers had official business on the premises.

The behavior appeared targeted. Lorain is not a one-street town. The odds of recurring, idle police presence at a specific barbershop—absent any disturbances or complaints—raises serious questions. The fact that this happened in the weeks leading up to the trial only heightens the suspicion.

There’s a term for this kind of presence: ambient intimidation. It doesn’t involve an arrest or direct confrontation. But it sends a clear message. The department may not have had evidence strong enough to convict, but it still had uniforms, vehicles, and visibility. And it wasn’t afraid to use them.

Pallens did what he’d done throughout the case—he documented it. With photos, notes, and digital timestamps, he created a timeline not just of where he was on June 24th, but of what he experienced in the months that followed. These weren’t the actions of a man hiding from the law. They were the acts of someone being watched for refusing to fold.

When asked about the surveillance, city officials offered no explanation. No justification. No clarification. Silence spoke volumes. In a city where public trust in law enforcement has been repeatedly tested, that silence felt like confirmation.

It is impossible to know whether these patrols were ordered, improvised, or simply coincidental. But in the context of a criminal prosecution based on an unverified civilian complaint, the optics are chilling. Law enforcement is entrusted to protect the public, not to shadow those it fails to convict.

Surveillance without cause is not just poor optics—it’s a cultural problem. It suggests a desire not for justice, but for compliance. Not for safety, but for silence. That a defendant acquitted by a jury still had to look out the window at squad cars staring back at him should be unacceptable in any city.

In the end, those photos became more than exhibits. They became a symbol of what this case was really about: control. The city may not have won in court, but it did everything it could to impose its presence, its power, and its pressure beyond the courtroom. Fortunately, the law still allows for one final check on that power—a jury. And this time, they weren’t buying it.

VII. No Witness, No Damage, No Case

If there was one defining characteristic of the State’s case against Elliut Pallens, it was absence: absence of video, absence of damage, absence of corroboration, and absence of honest investigation. The only person who claimed to have witnessed the alleged collision was Ashley Schilla. Her account wasn’t backed by photos, immediate statements, or physical documentation—just her word.

In fact, court records confirm that no damage was documented on the date of the alleged incident. Months later, subpoenas issued to Schilla included an unusual instruction: “Please bring proof of damages to court.” That detail is damning. It means that when charges were filed, the city had no visual record, no police photographs, and no physical inspection to justify any of the citations.

Moreover, Officer Gerace—the responding officer—did not witness the incident. He issued citations entirely based on Schilla’s word, never inspected the scene for physical evidence, and did not interview Pallens. There was no accident reconstruction, no body camera footage, and no crash report filed by Gerace. The entire legal action rested on hearsay.

Despite that, the city treated the accusation as settled fact. Citations were filed that same day. And while the prosecution would later subpoena Schilla to testify, no law enforcement follow-up appears to have occurred between the date of the citation and the date of trial. Months passed. The city made no effort to verify or validate Schilla’s story.

When Schilla eventually took the stand, she was unable to provide immediate photos from the scene or contemporaneous evidence of any damage. The lack of documentation—combined with the absence of corroborating witnesses—undermined her credibility. It became clear that no one other than Schilla could attest to the supposed crash.

Under ordinary circumstances, a case this thin would never make it to trial. The standard for criminal charges, even misdemeanors, is probable cause supported by objective evidence. But in Lorain, apparently, a single unsupported statement was enough to trigger four charges and a year of prosecution.

This is not just a failure of law enforcement. It’s a systemic lapse in prosecutorial discretion. By building a case without witnesses, photographs, or an actual investigation, the city exposed itself—not just to public criticism, but to legitimate legal liability.

No one from the city ever explained how this case advanced so far. No supervisor appears to have reviewed the body of evidence. No internal audit caught the absence of a crash report. And no one, apparently, asked the basic question: where is the proof?

The jury asked that question. And when the state could not answer it, they returned a verdict that spoke volumes. What they said was this: justice requires more than accusation. It demands evidence. And in the case of Elliut Pallens, there was none.

Final Thought

The case against Elliut Pallens never should have made it past the point of citation, let alone proceed to trial. It was a prosecution built on presumption, sustained by bureaucratic inertia, and exposed by one man’s unwillingness to yield to intimidation, coercion, or convenience. This wasn’t a legal proceeding—it was a performance, and every act of that performance was carried out at the expense of a working man’s peace, time, and dignity.

In a system that so often rewards quiet compliance, Pallens chose resistance. He chose to trust that the truth—meticulously documented, time-stamped, and irrefutable—would win out. And when it finally reached a jury, it did.

But we shouldn’t need a jury to fix what should have been dismissed outright. When prosecutors lean on plea deals to mask bad cases, when police write citations without observation, and when silence substitutes for accountability, the entire system falters.

This case wasn’t just about one man. It was about a city’s prosecutorial culture. It was about power exercised without caution. And it was about how far a person has to go to clear their name when the institutions around them stop caring about whether there was a crime in the first place.

Elliut Pallens walked out of the courtroom a free man. But the real verdict here is for the City of Lorain. Its leaders, prosecutors, and officers are now on notice—not just from a jury, but from a community that is watching, remembering, and asking who’s next.

Disclaimer: All documents, quotes, and exhibits referenced in this article are derived from public records, subpoena filings, and direct communications provided to the reporter. Any individuals referenced are presumed innocent of any unrelated matters. This article is presented for public accountability and journalistic transparency and does not constitute legal advice or accuse any party of criminal wrongdoing beyond what was substantiated in open court or legal filings.