By Aaron Knapp | Lorain Politics Unplugged

⚡️ Legal Disclaimer

All quotes and references in this report are taken directly from the official sworn deposition of Lorain County Prosecutor JD Tomlinson, dated February 2024, and corroborated through verified public records.

Thanks for reading Aaron’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I. The Moment He Knew

When exactly did JD Tomlinson learn about the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) complaint filed against him by Jennifer Battistelli? That simple question was met with a maze of uncertainty during his sworn deposition.

“I don’t recall,” Tomlinson said repeatedly. But then, in one moment of clarity, he admitted: “I would have read it within a day or so of it being submitted.” (Tomlinson Deposition, p. 4)

Despite that, he took no formal steps to notify the Board of Commissioners, the public, or the County’s insurer. Nor did he disclose the complaint as a potential liability at any open meeting. When asked if he told anyone at the Board what the complaint alleged, he replied: “No. It was an internal matter.” (p. 6)

Pressed further, Tomlinson conceded that his office treated it like any other HR grievance: “It didn’t rise to the level of something that needed to go to the Board.” (p. 6) But that stands in sharp contrast to the nature of the allegations—including coercion, sexual misconduct, and workplace retaliation. Those are not routine HR issues. They are potentially criminal.

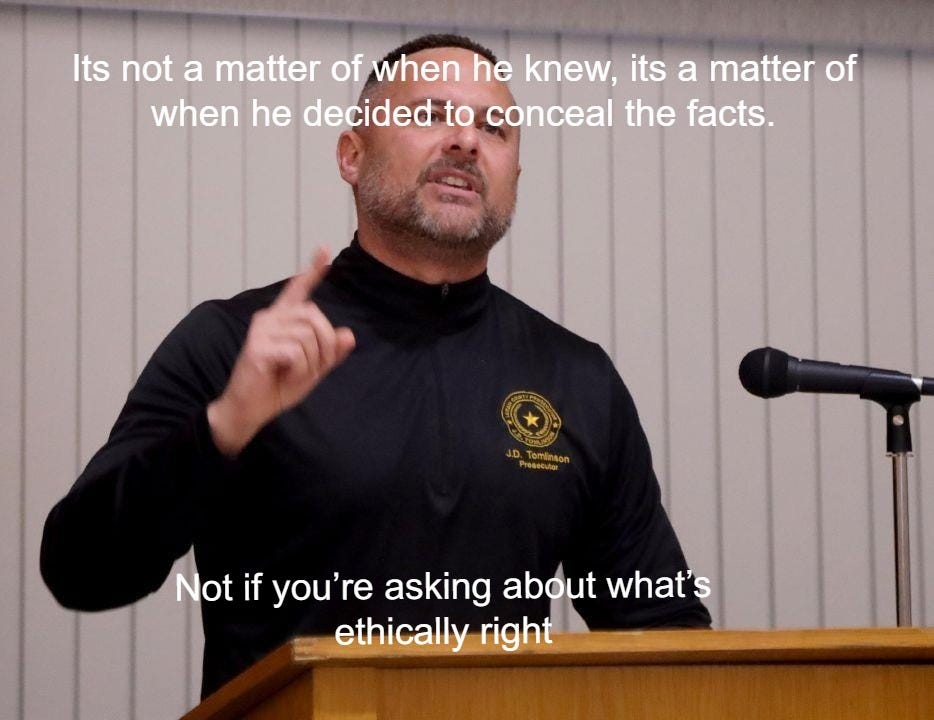

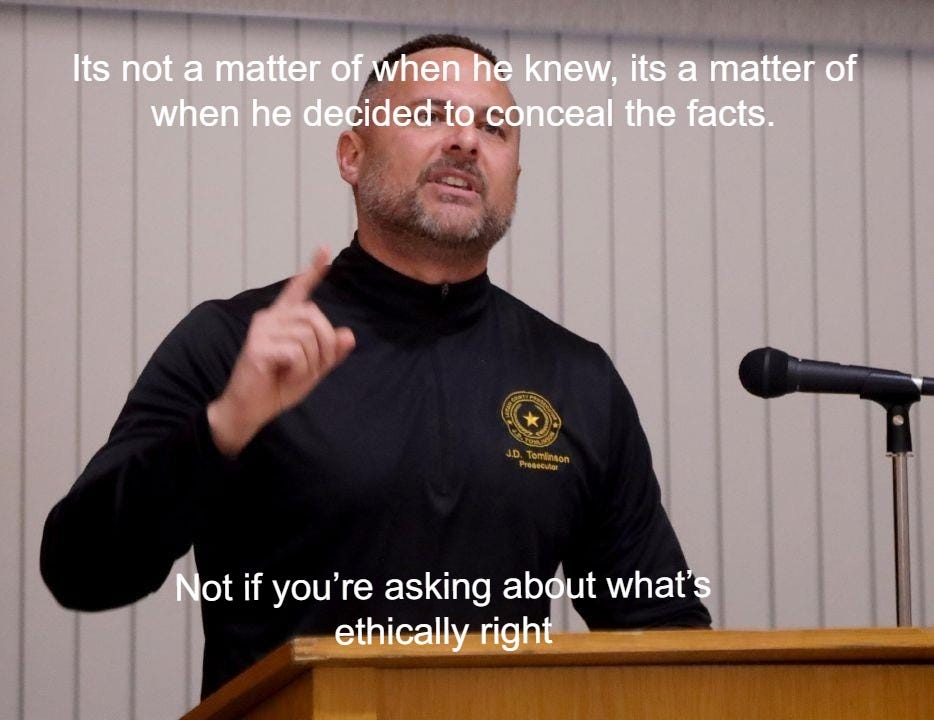

Yet under oath, the County’s top law enforcement officer drew a line in the sand: “Not if you’re asking about what’s ethically right,” he said, when asked if he believed withholding the complaint from the Board was appropriate. (p. 7)

His testimony revealed a pattern of compartmentalization. Rather than subject the allegations to public review or oversight, Tomlinson quarantined the matter inside his office. That decision shaped every event that followed—the secrecy, the payment, and the misdirection of public funds.

This moment in the deposition sets the tone. Tomlinson acknowledged early awareness of the complaint and opted for silence. Not out of confusion. Out of strategy.

His actions weren’t those of a public servant navigating complexity. They were the maneuvers of a man protecting himself from institutional consequence.

II. Not If You’re Asking About Ethics

That quote—“Not if you’re asking about what’s ethically right”—may go down as one of the most damning moments in JD Tomlinson’s career. Under questioning, he didn’t claim ignorance of the complaint. He didn’t deny its seriousness. He simply dodged the ethical implications. (p. 7)

Asked directly whether the Board should have been informed prior to approving a $100,000 settlement, Tomlinson deflected: “They had the ability to request documents,” he claimed. (p. 10) But the commissioners have all testified they were unaware of the complaint until after the settlement had been paid.

Commissioner Michelle Hung testified: “Absolutely not. I would have had so many questions, and they know it.” (Hung Deposition, p. 45) She also stated she never saw the complaint before the vote and was given just an hour to review the settlement documents.

Tomlinson, on the other hand, asserted that all necessary disclosures were made internally. “We followed our process,” he said. (p. 11) But no documentation has emerged showing any formal notification to the Board.

When asked if withholding that information shielded his office from scrutiny, Tomlinson offered no direct answer. But when pressed on whether the EEOC complaint accused him of a crime, he paused, then said: “I haven’t reviewed it that way.” (p. 13)

Even when confronted with the fact that the complaint alleged sexual assault and quid pro quo misconduct, Tomlinson declined to acknowledge its seriousness: “I’m not sure how that would be characterized in legal terms.” (p. 13)

Tomlinson’s deposition is riddled with this kind of evasion—where technicalities replace accountability, and form is used to override substance.

His refusal to call what happened a conflict, or to seek outside legal review, exposes a deeper ethical void: one where personal preservation trumps public responsibility.

III. What He Didn’t Tell the Commissioners

One of the most troubling aspects of the deposition is what Tomlinson never told the commissioners. He didn’t tell them Battistelli had filed an EEOC complaint. He didn’t tell them the settlement was related to sexual misconduct allegations. He didn’t tell them that the $100,000 payout included personal liability mitigation for himself. (p. 11–14)

Instead, the settlement was submitted as a routine legal bill—classified under “supplies and services.” Commissioner Hung recalled, “Dan Petticord told me it was a legal bill and the appointing authority says it has to be paid.” (Hung Depo, p. 41)

No mention of criminal accusations. No indication of ethical risk. Just a budget line item with no context.

Tomlinson didn’t advise the Board to seek outside counsel. He didn’t recuse himself from handling his own complaint. He didn’t submit the issue for review by any neutral agency.

And yet, when asked under oath if he believed the public had a right to know, he admitted: “Yes.” (p. 15)

He was asked whether failing to notify the Board shielded him from political fallout. He replied, “That’s not how I look at it.” (p. 14)

But the result is clear. The settlement was paid without scrutiny. The complaint remained sealed. And the Board, by his design, never had a chance to intervene.

This was not a system breakdown. It was deliberate omission.

IV. A Settlement Signed in Shadows

The public record shows the $100,000 payment was pushed through as a late add to the commissioners’ agenda. Commissioner Hung testified she saw the requisition only an hour before the vote. (Hung Depo, p. 33) She had to ask her assistant to fetch the settlement agreement manually. Even then, the full complaint remained hidden.

Tomlinson took no action to ensure transparency. In fact, his assistant prosecutor, Dan Petticord, instructed the Board that no public records would be released unless approved by his office. That’s why the EEOC complaint was only released months later—after a court ordered its disclosure. (Hung Depo, p. 24; Relator’s Exhibits 1–5)

Tomlinson claimed in his deposition: “It was handled through our normal HR and legal process.” (Tomlinson Depo, p. 9) But nothing about the process was normal. Legal bills were reclassified. Commissioners were misinformed. And documents were concealed.

He later claimed: “I didn’t see a need for external involvement.” (p. 12) But he also conceded: “I guess I could have brought it up earlier.” (p. 12)

This push-pull of excuse and acknowledgment defines his testimony.

The absence of an executive session. The rerouting of liability. The lack of a public vote. These are not bureaucratic oversights. They are red flags.

And Tomlinson, when asked about the public’s right to know, simply said: “That depends.” (p. 15)

V. Under Oath, Under Scrutiny

It took nearly two years, multiple lawsuits, and dozens of subpoenas to get JD Tomlinson under oath. But when he finally sat down for his deposition, what emerged was not a story of oversight or miscommunication. It was a portrait of willful omission.

He didn’t forget. He concealed.

He wasn’t confused. He was calculated.

Tomlinson spoke often of “internal processes,” but never once acknowledged the public interest at stake. He characterized a six-figure settlement stemming from an EEOC complaint as an administrative matter. When pressed on whether the public should have known before the check was cut, he conceded only, “Maybe.” (p. 16)

In the end, the most honest quote he gave may have been the simplest: “Not if you’re asking about what’s ethically right.” (p. 7)

That was the moment the mask slipped.

It’s rare that a sworn deposition lays bare the mechanics of concealment so plainly. But here it is—in black and white. Verified. Transcribed. And now, publicly read into the record.

Author’s Opinion: The Prosecutor Without a Prosecution

Lorain County needed a prosecutor who pursued justice. Instead, it got a political manager who protected himself. JD Tomlinson didn’t investigate. He avoided investigation. He didn’t enforce accountability. He buried it.

There were countless off-ramps—moments when he could have disclosed the complaint, paused the settlement, or submitted the matter to independent review. He took none of them. Instead, he relied on legalistic obfuscation and a compliant assistant prosecutor to help him push the matter quietly out the door.

For that, voters removed him. And they were right to do so.

Now the full record is public. The deposition speaks for itself. The EEOC complaint has been read into history. What’s left is for the new prosecutor—and the people of Lorain County—to ensure this never happens again.

📄 Final Legal Disclaimer

This article is based entirely on the sworn deposition of JD Tomlinson, public records, and associated legal filings. All quotes are taken directly from official transcripts and verified materials. Allegations and testimony are presented for public awareness and civic accountability.