When a Sheriff’s Office Says “No Record” After an In Person Evidence Handoff, That Is Not a Clerical Error

A breaking accountability report on disputed custody, a command level meeting, and the problem of conflicted gatekeepers

By Aaron Christopher Knapp

Investigative Journalist

Lorain Politics Unplugged

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

There are certain phrases government agencies reach for when a problem needs to be reduced in size without being resolved. “No record” is one of the most powerful among them. In its proper context, it is unremarkable. Sometimes a document truly does not exist. Sometimes a request seeks a category of record that was never created. In those situations, “no record” is a factual response to a factual inquiry.

But context determines meaning. When “no record” is asserted after a scheduled, in person, face to face meeting attended by senior officials, where physical documents were handed directly to command level personnel and discussed for purposes of review, the phrase changes character. It stops functioning as a neutral administrative reply and becomes an institutional position. It becomes an act of denial that carries consequences. At that point, the phrase is no longer the end of the story. It is the story.

This piece documents a dispute that has crossed that threshold. A discrete packet of physical documents was delivered during an in person meeting with senior representatives of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office. The meeting was not incidental. It was convened specifically to address the contents of those documents and to determine what, if any, review was warranted. The materials were physically placed into the possession of a command level officer in the room, in the presence of another senior official. The Sheriff’s Office has now taken a position, in written correspondence, that it has no record of receiving those materials or that the materials are not within its possession or control.

That posture does not merely implicate filing systems. It does not merely raise the possibility of a misplaced folder. It raises questions about custody, internal controls, institutional truthfulness, and the structural conflict created when the same individuals who were present for receipt now occupy the role of evaluators and gatekeepers for any outside review. When an agency that accepted physical documents in a command setting later asserts “no record,” the issue is not clerical. It is institutional.

All persons referenced in this reporting are presumed innocent of wrongdoing. The analysis presented here is grounded in documented correspondence and contemporaneous descriptions of events. This article is published for news, commentary, and public accountability purposes under the First Amendment. It is not legal advice.

1. The Core Problem: “No Record” After a Physical Handoff

There are phrases government agencies use when they want to shrink a serious problem into something manageable. “No record” is one of them.

Sometimes it is legitimate. Sometimes a document truly does not exist. Sometimes an agency was never asked to create something. Sometimes nothing was received.

But when “no record” is invoked after an in person, face to face, command level meeting where physical documents were handed across a table and discussed, the phrase stops being an administrative answer and becomes the story.

On February 6, 2026, a representative of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office responded in writing:

“According to Major Scharschmidt, Agent Mike Massie, the Sheriff, and Director Nici, they do not have any record of the documents you indicated were provided.”

Read that carefully.

They did not deny that a meeting occurred. They did not deny that documents were discussed. They did not deny that concerns were reviewed. They denied having “any record” of the documents being provided. That distinction is not semantic. It is structural.

In a normal institutional environment, chain of custody is not dramatic. It is routine. Someone receives something. The agency logs it. The agency routes it. The agency preserves it or disposes of it under a policy. Months later, if asked what happened to it, the agency pulls its own intake documentation and explains.

It does not demand that the reporting party reconstruct internal failures from memory. It does not ask the person who delivered materials to supply affidavits to cure gaps in its own logging practices.

What makes this dispute extraordinary is not that a citizen claims he mailed something and cannot prove it. What makes it extraordinary is that the described delivery occurred during an in person meeting attended by senior personnel, including the very administrative official now speaking for the office in correspondence.

That creates a structural conflict. The dispute is not merely about a document. It is about the credibility and neutrality of the office asserting the denial while controlling the process that would evaluate that denial. The written response is not a casual statement. It is institutional. It lists names. Major Scharschmidt. Agent Massie. Sheriff Hall. Director Nici. The denial is collective. Coordinated. Official. And that is precisely why it cannot be minimized. Once a law enforcement agency affirmatively states that it has “no record” of materials that were physically handed over and discussed in its presence, the issue is no longer clarification. It is no longer recollection.

It becomes an evidence integrity issue.

A post closure denial does not become less serious because an agency says a matter is closed. Closure often increases the likelihood of oversight, civil litigation, public records disputes, and external review. Closure does not extinguish the duty to account for what was accepted. Closure does not erase the obligation to truthfully describe what occurred. Closure does not make evidence disappear. When an agency moves from uncertainty to affirmative denial in writing, it is not simply managing paperwork. It is taking a position. And when the same officials who were present for receipt are also positioned as arbiters of whether receipt occurred, neutrality is no longer intact. That is the core problem. Not paperwork. Not memory. Institutional credibility.

________________________________________

2. What Was Delivered and Why It Matters

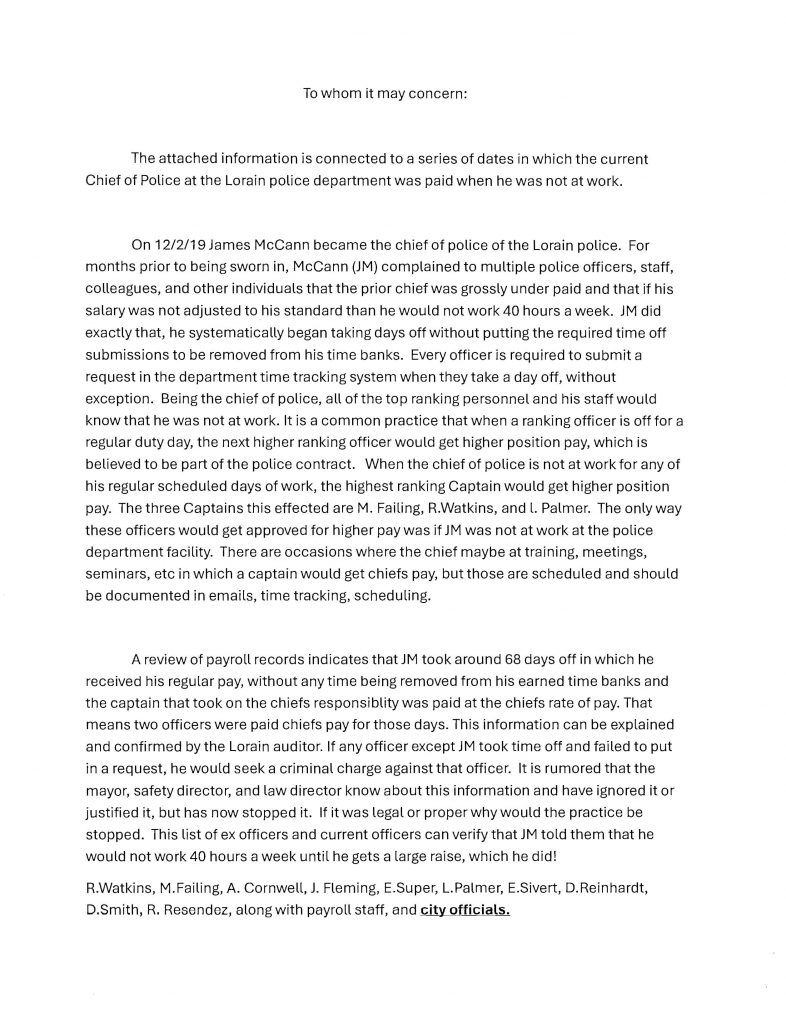

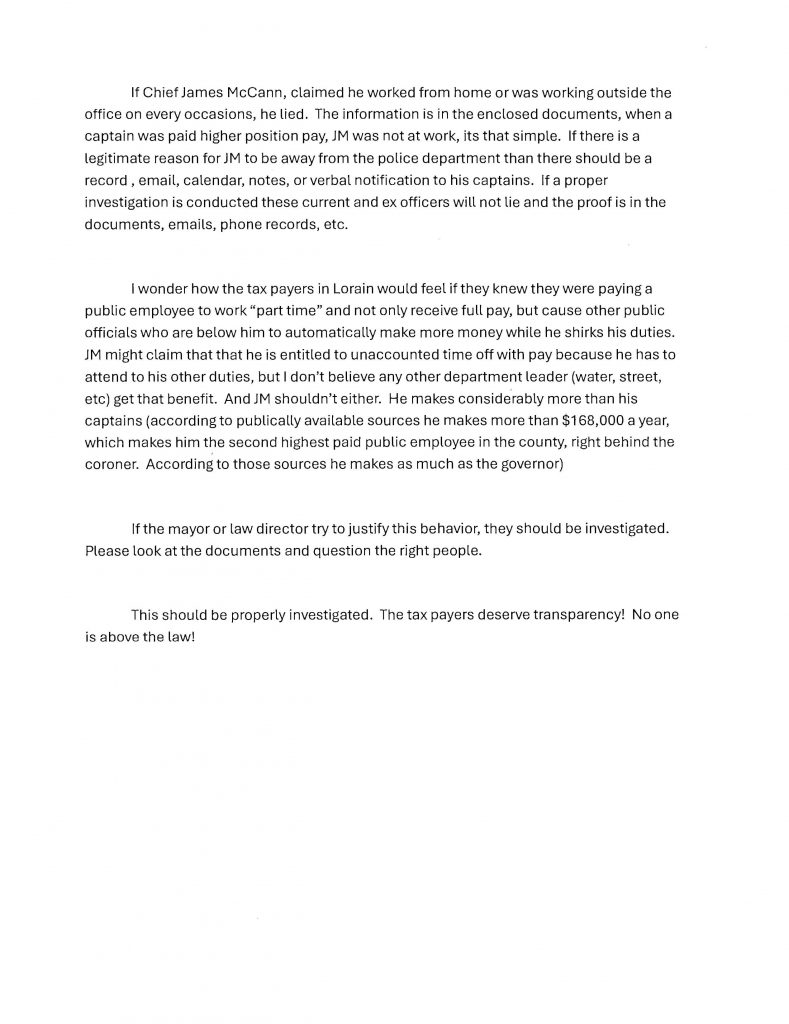

The packet at issue was not described as loose notes, an informal tip, or a vague narrative complaint. It was described as a defined, physical collection of documents delivered together, in a single transfer, during a scheduled in person meeting convened for the purpose of discussing those materials. The descriptive inventory has been intentionally detailed and intentionally repetitive because repetition is the mechanism that eliminates ambiguity. When an office later implies uncertainty, the antidote is specificity so complete that no reasonable reader can claim confusion about what was meant. The delivery was not casual. It was not mailed. It was not slid under a door. It occurred face to face, in the presence of command level personnel, during a meeting convened to review the substance of what was being provided. That fact alone distinguishes this from the ordinary situation in which a citizen asserts that something was sent but cannot demonstrate receipt. Here, the assertion is that materials were physically handed over, accepted, and discussed in the room. That is a materially different posture.

The packet, as described in the formal response, consisted of an addressed envelope with no return address, a typed explanatory letter, payroll and timekeeping records generated from the City of Lorain payroll system originating from the Auditor’s Office, and additional correspondence described as minimal in independent consequence but provided for contextual completeness. Those are not abstract references. They are physical artifacts. They have weight. They have formatting. They have ink. They have a container. They have identifiable characteristics that would allow any good faith internal search to locate them if standard intake procedures were followed.The envelope itself matters because it is an identifying container with a unique addressing feature and the absence of a return address. The explanatory letter matters because it contextualized the enclosed records and explained why they were being preserved. The payroll and timekeeping records matter because they were official, government generated documents printed from a municipal payroll system, formatted in tabular form, containing employee identifiers, dates, pay codes, classifications, and compensation entries. These were not summaries created by a private citizen. They were records generated in the ordinary course of government business. The additional correspondence, though described as minimal in independent consequence, was provided so that the reviewing agency would have the broader context rather than a narrow slice of it.Specificity removes escape routes. When the contents are described down to paper type, formatting, origin, and delivery method, the “we did not understand what you meant” defense collapses. What remains is not ambiguity. What remains is a question about intake, routing, logging, and custody control inside the receiving agency.

In other words, the packet is not an abstraction. It is paper, ink, formatting, and a container. Even if someone later attempts to minimize the significance of the contents, the physical nature of what was delivered makes a “no record” posture far more difficult to reconcile without raising deeper institutional questions. Those questions are not rhetorical. They are operational. They go to whether evidence intake procedures were followed, whether documentation was logged, and whether command level acceptance was memorialized in any way. When a defined, physical packet delivered in person during a scheduled meeting is later described as having no record of receipt, the burden shifts. It no longer rests on the person who delivered it to prove that paper exists. It rests on the institution that accepted it to explain what happened to it.

________________________________________

3. The Meeting: Why the Date Question Belongs to the Sheriff’s Office

One of the oldest bureaucratic maneuvers in disputes involving government agencies is to shift the burden of precision onto the citizen. Demand a date. Demand a minute. Demand a calendar entry. Then, if the citizen hesitates or qualifies an answer, imply that uncertainty equals unreliability. It is a tactic that attempts to convert institutional responsibility into personal recollection.

In the context of a command level meeting inside a law enforcement agency, that maneuver does not withstand scrutiny. The Lorain County Sheriff’s Office maintains calendars. It maintains internal scheduling systems. It maintains email correspondence. It maintains meeting logs. It maintains administrative records of command staff activity. The suggestion that the reporting party must supply the precise calendar date of a meeting attended by senior personnel in order for the agency to confirm its own records reverses the burden in a way that is neither neutral nor reasonable.

The response letter properly refuses that trap. It does not speculate. It does not guess. It does not invent certainty where documentation should exist. It states clearly that the meeting occurred. It identifies the participants present in the room. It identifies the purpose of the meeting. It identifies the fact of physical delivery. It then states what should be obvious: the precise calendar date is properly verified through the agency’s own institutional records rather than through a citizen’s memory reconstruction exercise.

“Mr. Knapp is not the institutional record keeper. The Lorain County Sheriff’s Office is.”

That is not rhetoric. It is structural reality. When a meeting occurs between a citizen and command level law enforcement personnel, the agency is the entity with the obligation and capacity to memorialize that meeting. If the agency now asserts that it has no record of receiving materials during that meeting, it cannot logically insist that the reporting party supply the missing institutional record through affidavit or recollection. The absence of an entry in an internal system does not shift responsibility to the person who walked into the building and handed over documents.This matters because the date question is not a neutral request for clarification. In this posture, it risks becoming a device to manufacture doubt. If the reporting party supplies a date and it does not align perfectly with an internal calendar entry, the agency can imply inconsistency. If the reporting party declines to guess without consulting his calendar, the agency can imply vagueness. Either way, the agency attempts to position itself as the passive party awaiting precision, when in fact it controls the systems capable of verifying the event.

A command level meeting is not invisible. It leaves traces. It appears on calendars. It generates emails. It may involve room reservations. It may involve follow up communications. It may be referenced in subsequent correspondence. The burden to reconcile those internal records belongs to the office that maintains them. When an agency states that it has no record of receiving what was physically handed over, it cannot simultaneously claim that the absence of a citizen supplied date resolves the dispute. Institutional memory is not reconstructed by pressing a reporting party to guess. It is reconstructed by reviewing the agency’s own logs, calendars, and communications. The meeting occurred. The participants have been identified. The purpose has been identified. The physical handoff has been described. If the Sheriff’s Office wishes to contest that reality, it must do so based on its own records, not by attempting to convert institutional record keeping into a test of a citizen’s recall.

4. Fear, Risk, and Why Counsel Was Consulted Before Delivery

One of the most revealing facts in this dispute is not the inventory of documents. It is the state of mind behind the delivery. The reporting party was not casually walking into a building with loose papers. He was apprehensive. He understood the sensitivity of what he had received. He understood that the materials implicated high level conduct. He understood that once the documents left his possession, he would no longer control what happened to them.

That apprehension was not paranoia. It was prudence.

The packet had arrived anonymously. It contained government generated payroll and timekeeping records. It suggested compensation practices that warranted scrutiny. Turning such material over to a law enforcement agency is not a neutral act. It exposes the reporting party to risk. Risk of retaliation. Risk of being labeled adversarial. Risk of being characterized as politically motivated. Risk of later being accused of withholding, manipulating, or selectively releasing information.

That is why counsel was consulted before delivery.

The response letter now makes that clear in direct terms. Counsel was advised of the existence of the packet. Counsel reviewed the nature of the materials. Counsel understood both the potential significance of the records and the institutional dynamics surrounding them. Counsel also understood the foreseeable danger that, if the documents remained solely in the reporting party’s possession, a later narrative could emerge claiming that the materials were never shared, were selectively disclosed, or were strategically withheld.

On counsel’s advice, the most prudent course was chosen: deliver the full packet intact to the Sheriff’s Office, in person, to command level personnel, during a meeting convened for the express purpose of discussing the concerns raised. That course of action was not impulsive. It was deliberate. It was risk managed. It was intended to create transparency, not leverage. That decision matters now because it destroys any convenient narrative that the reporting party acted recklessly, theatrically, or in bad faith. The decision to consult counsel before delivery reflects the opposite. It reflects caution. It reflects awareness of institutional power imbalances. It reflects an understanding that once documents enter the custody of a law enforcement agency, control shifts. It also underscores how severe the current denial posture is. When a citizen, acting on advice of counsel, turns over sensitive materials to command level personnel in order to ensure neutrality and avoid accusations of withholding, and the agency later responds with “no record,” that posture does more than create a dispute. It validates the very fear that led to counsel being consulted in the first place.

The consultation was meant to prevent future controversy. The delivery was meant to prevent accusations of concealment. The in person transfer was meant to eliminate ambiguity. A post delivery denial does not simply contradict the reporting party. It calls into question the institutional safeguards that were relied upon when counsel advised that the documents should be turned over intact.That is not a minor detail. It is the reason this dispute now transcends paperwork and enters the territory of institutional trust.

5. Originals Still Matter, Even If Copies Exist

Agencies sometimes try to diminish a custody dispute by pointing to the existence of electronic copies. They imply that if the citizen has PDFs, then the original hard copy does not matter. That implication is not just incomplete. It is legally and practically wrong.

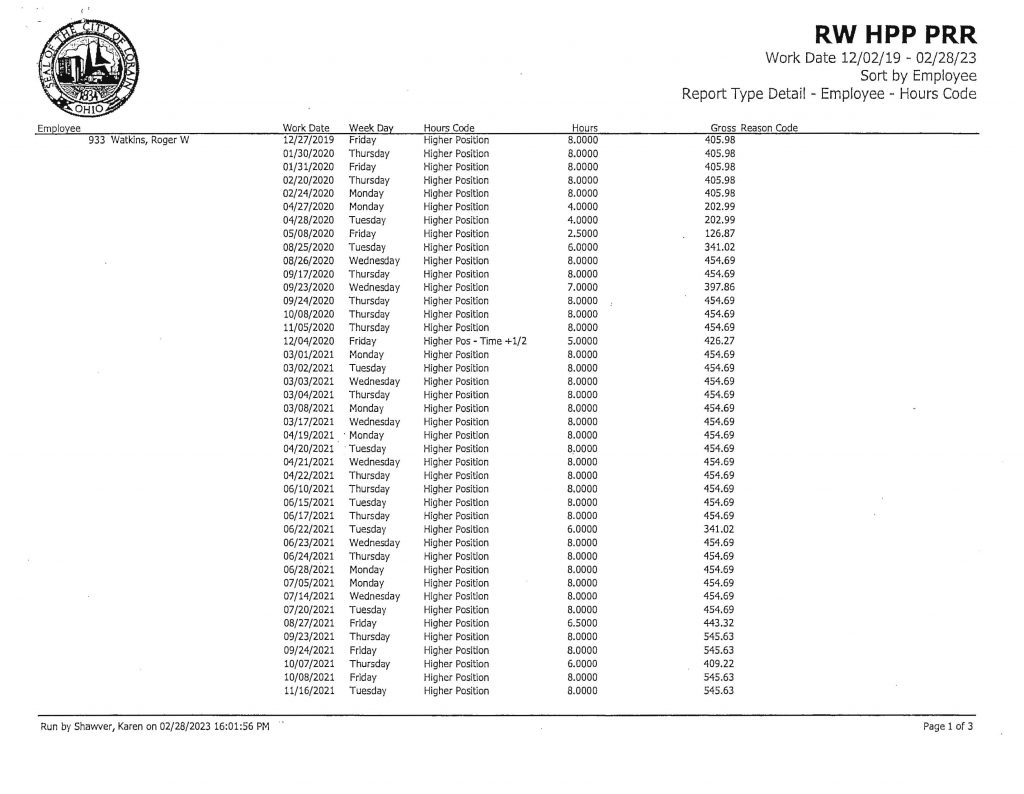

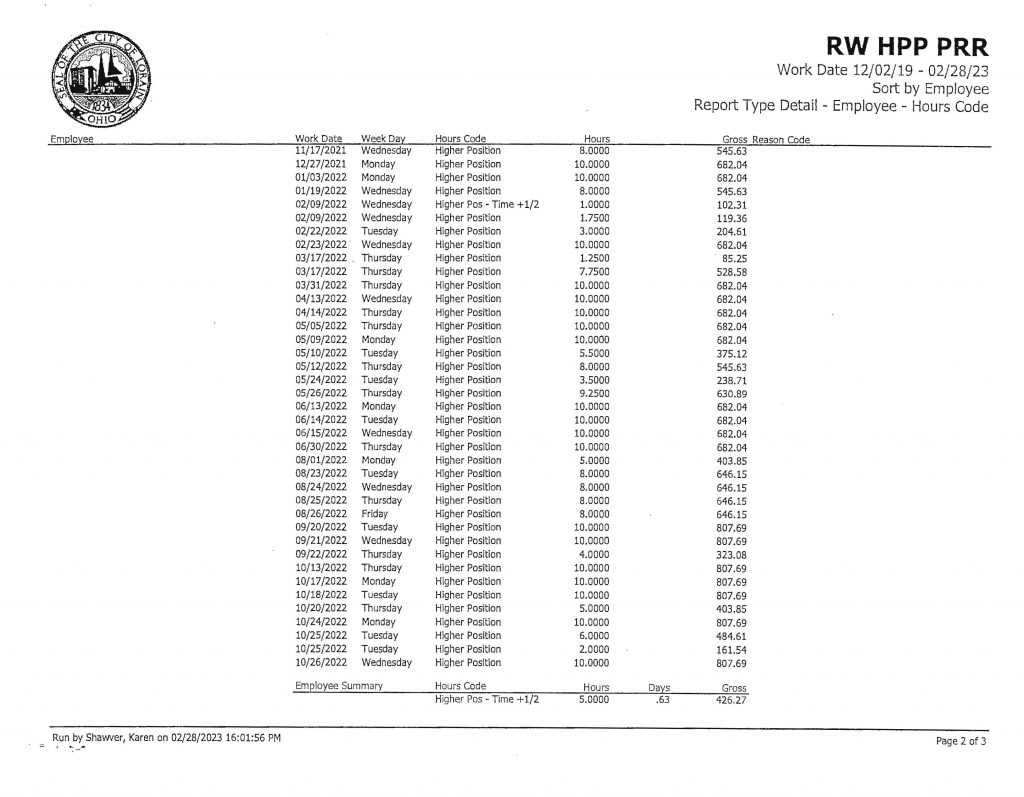

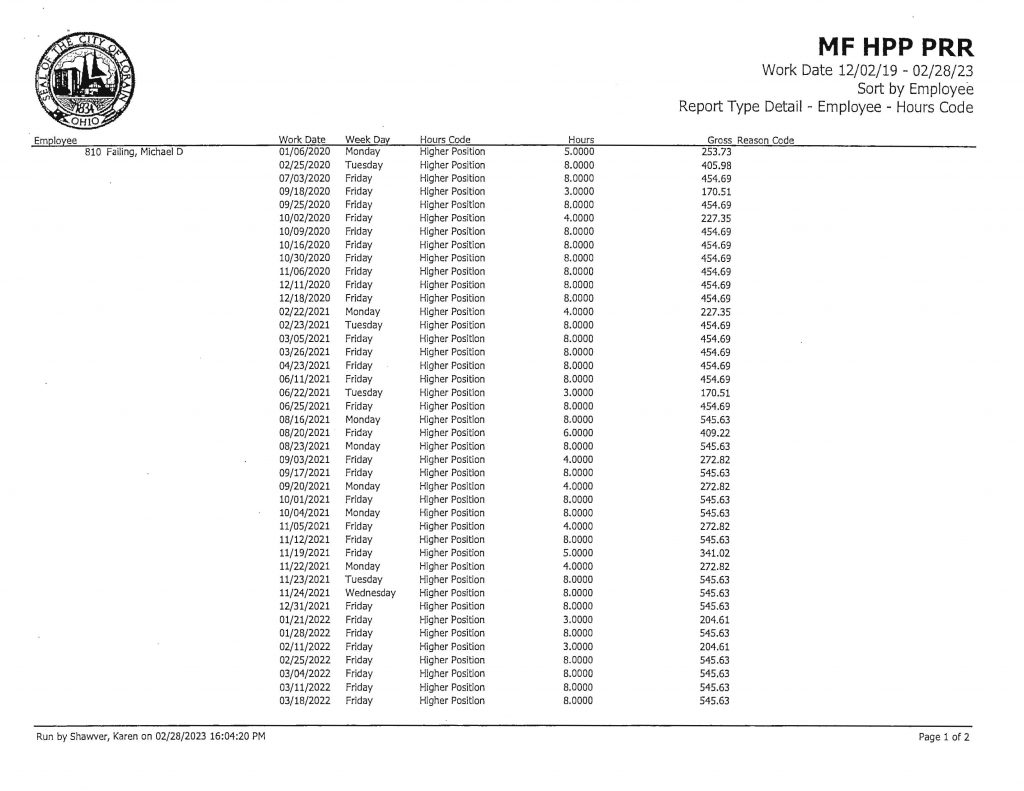

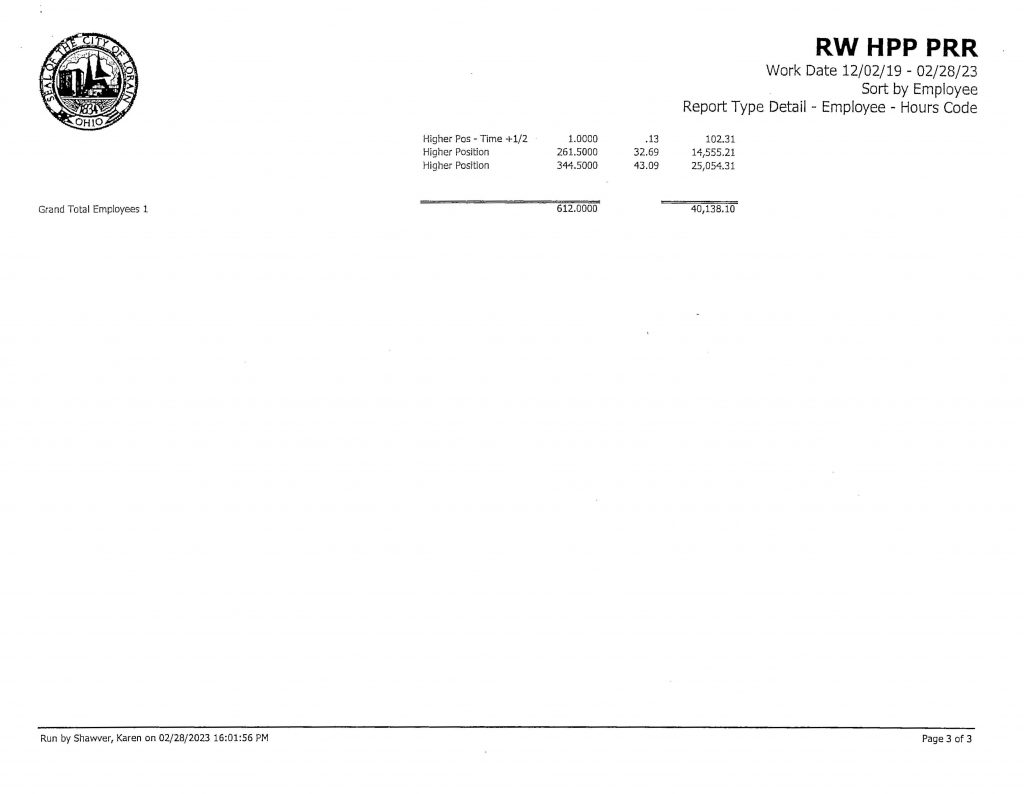

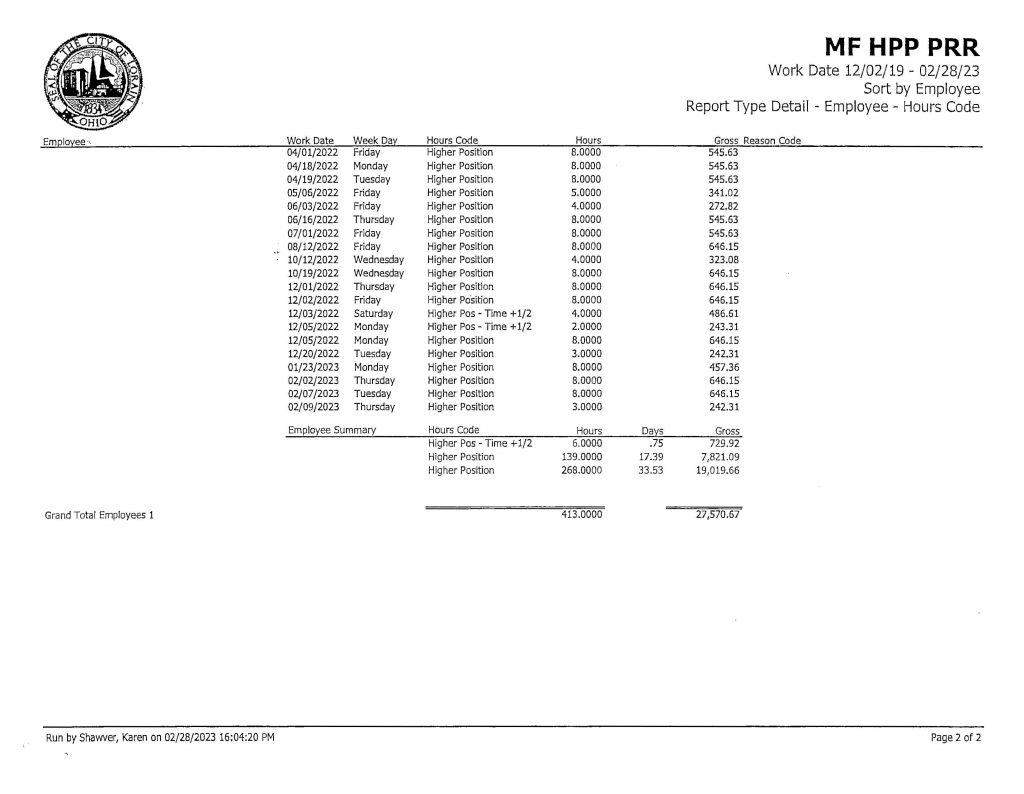

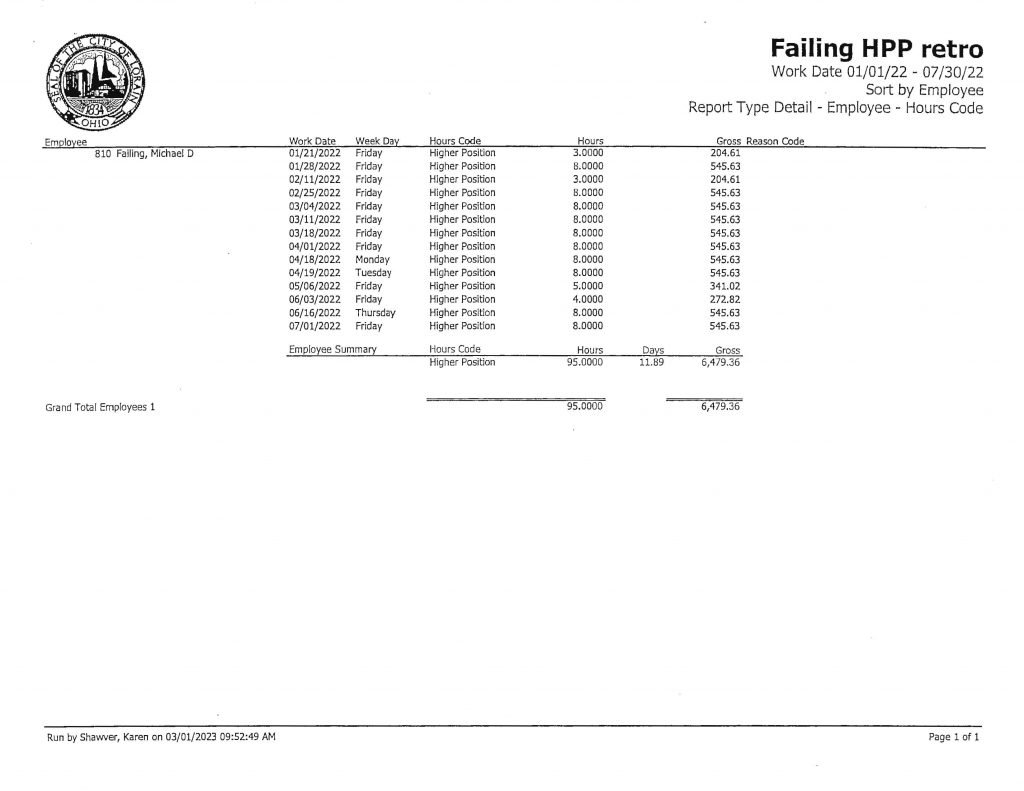

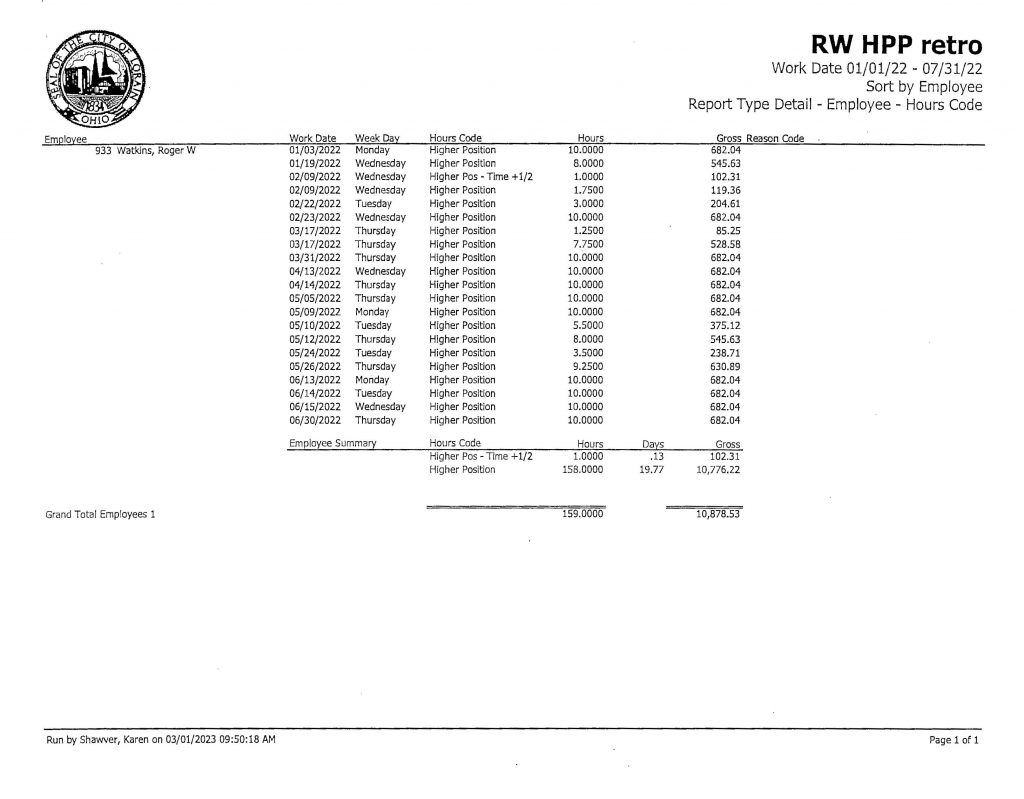

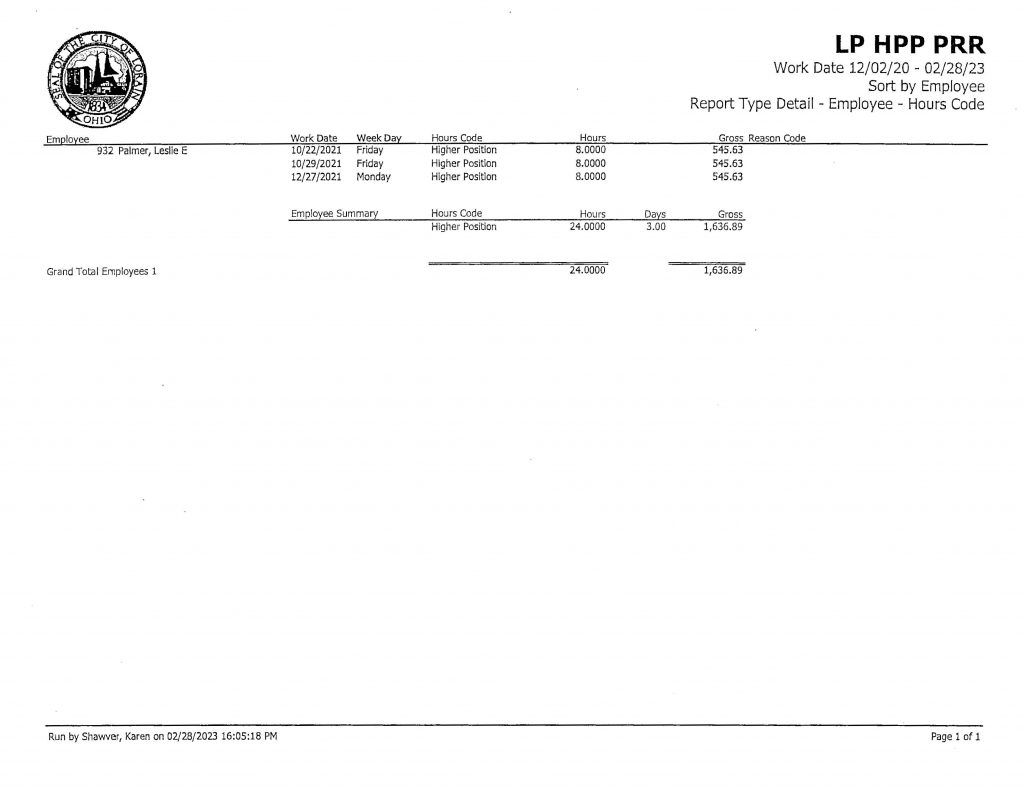

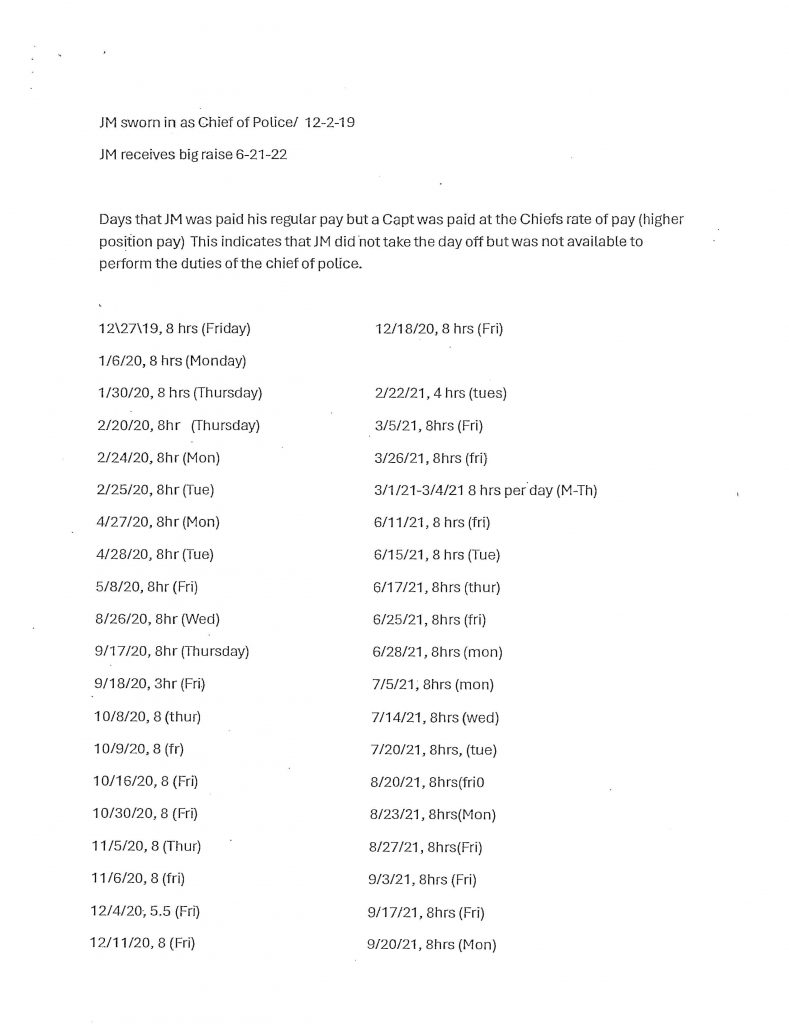

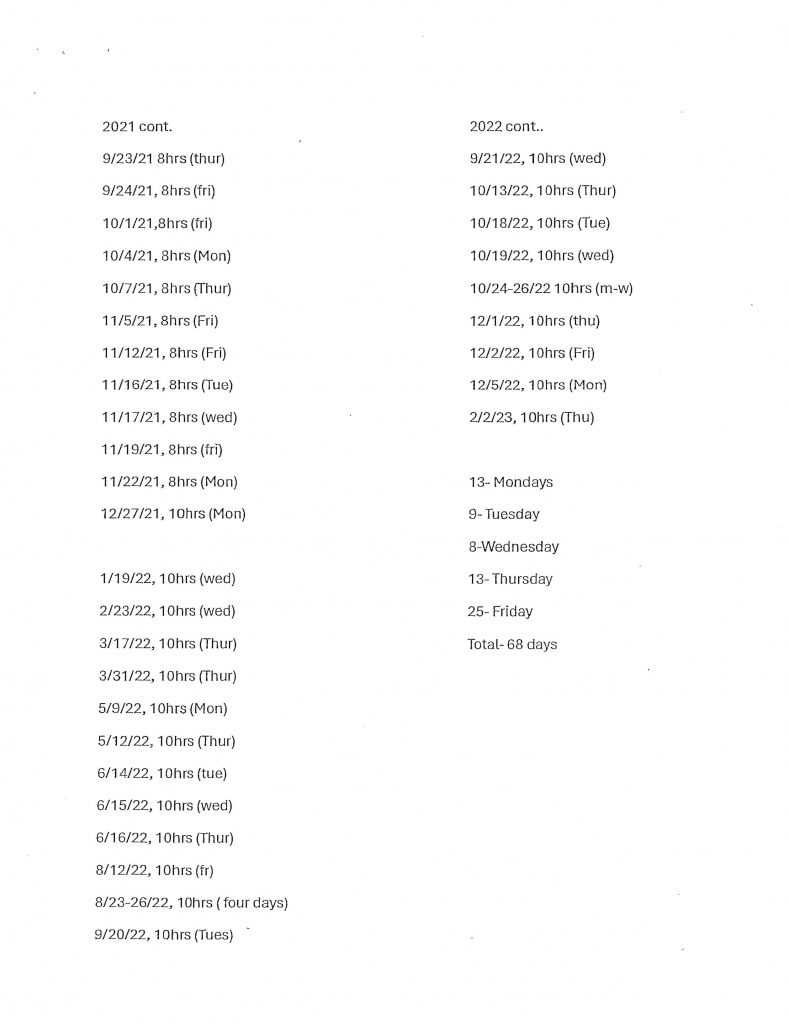

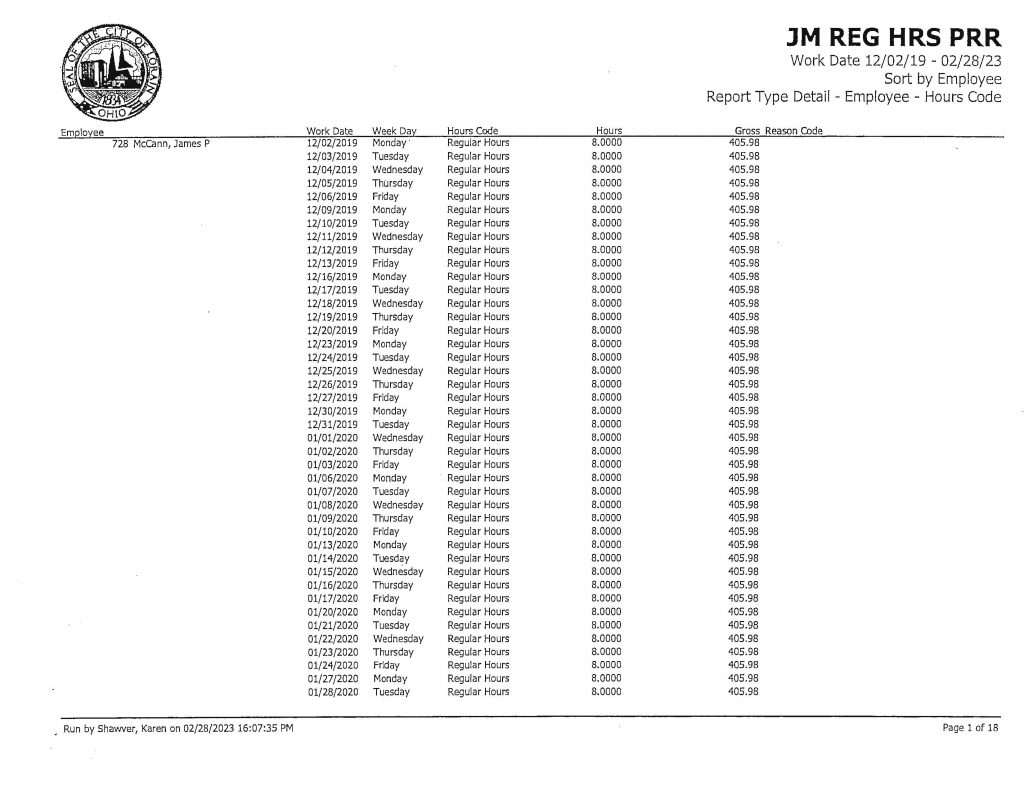

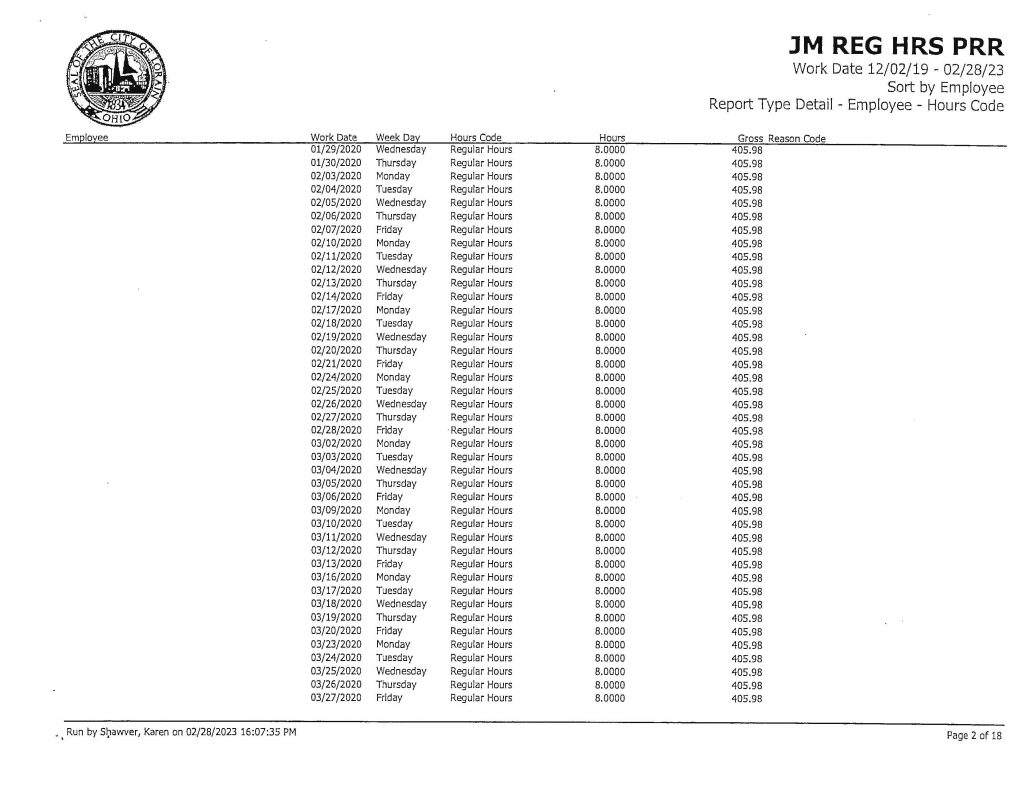

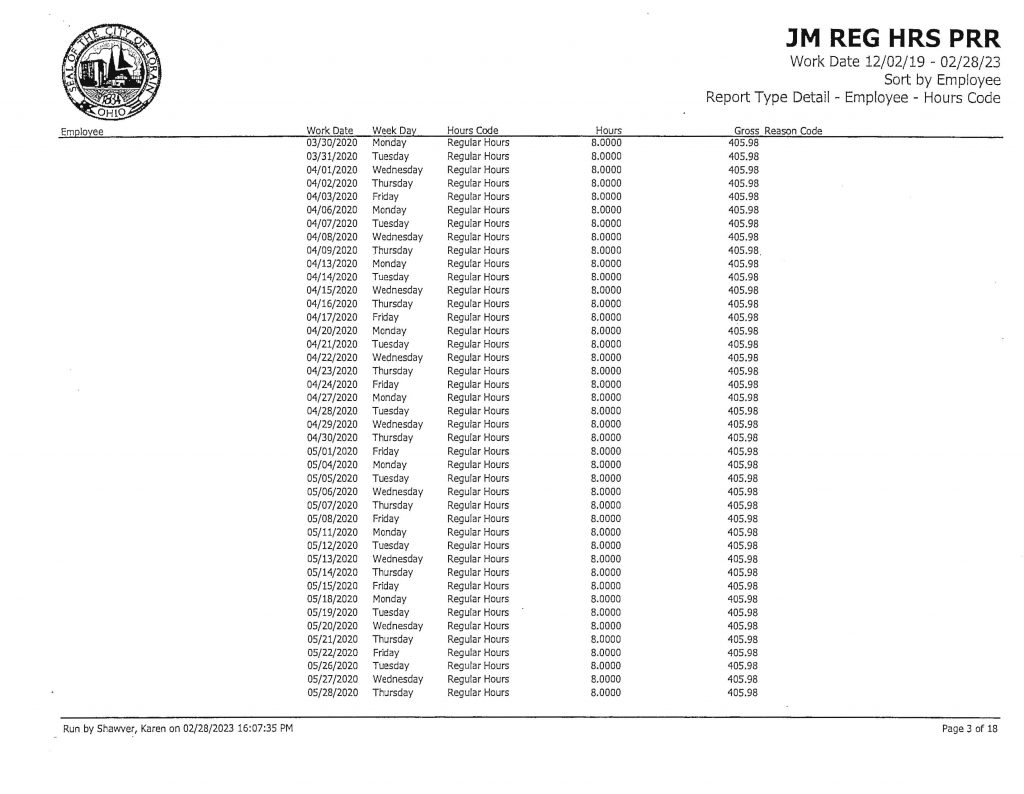

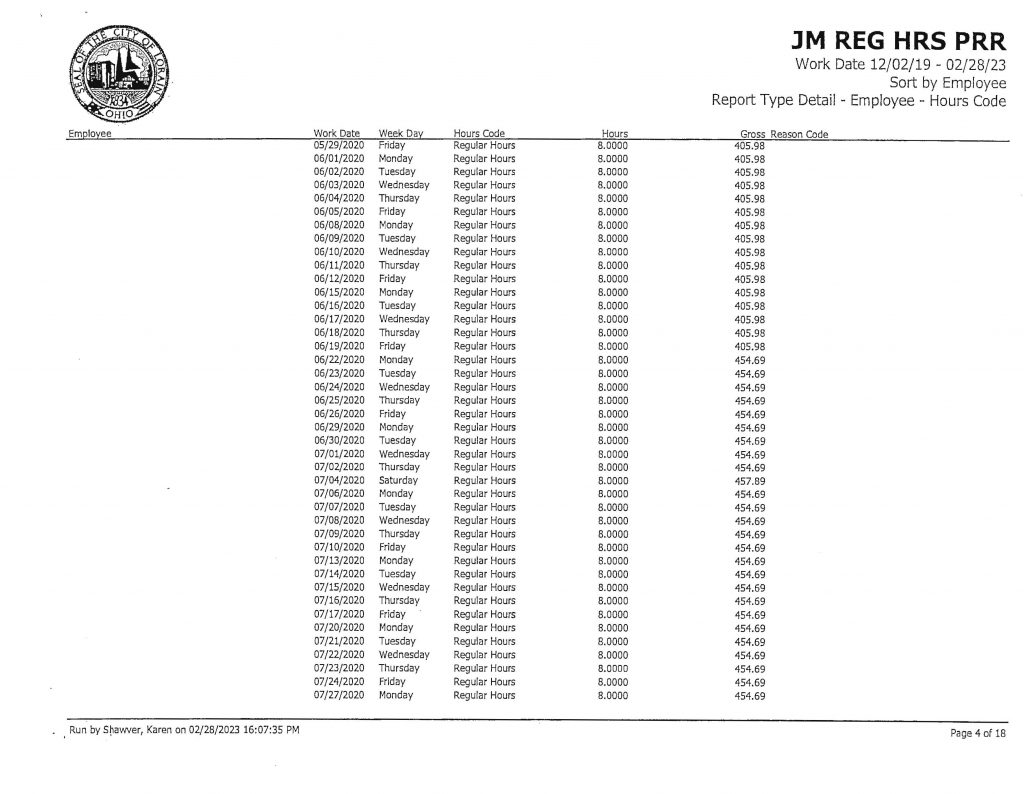

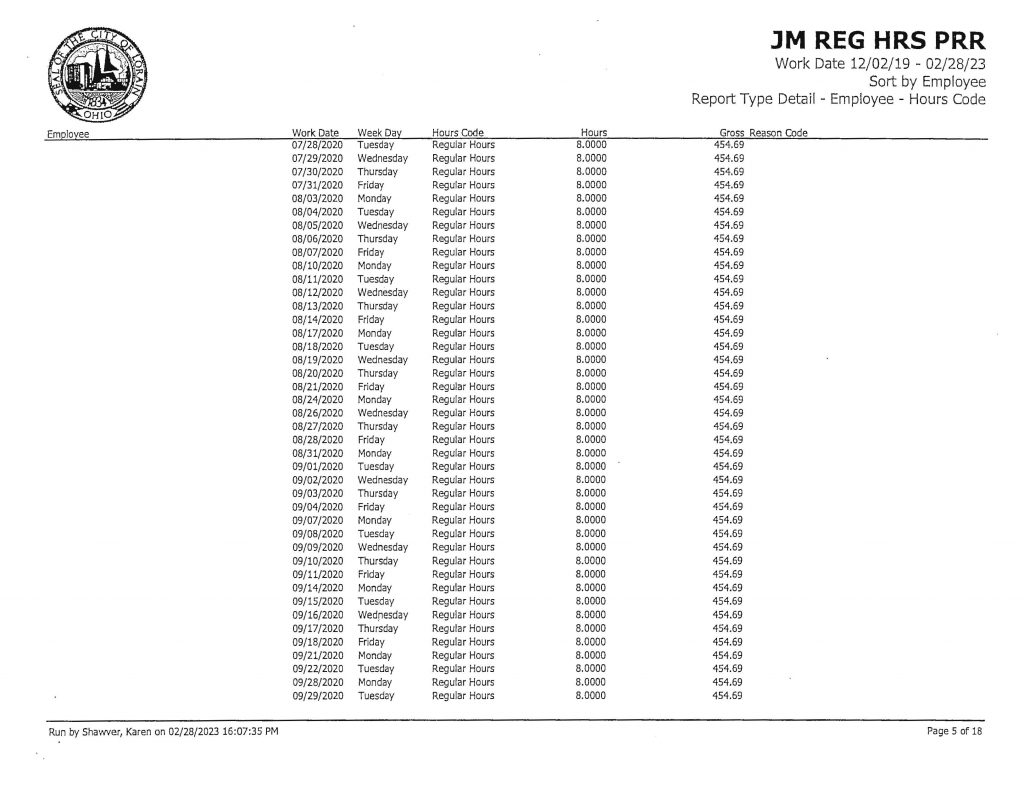

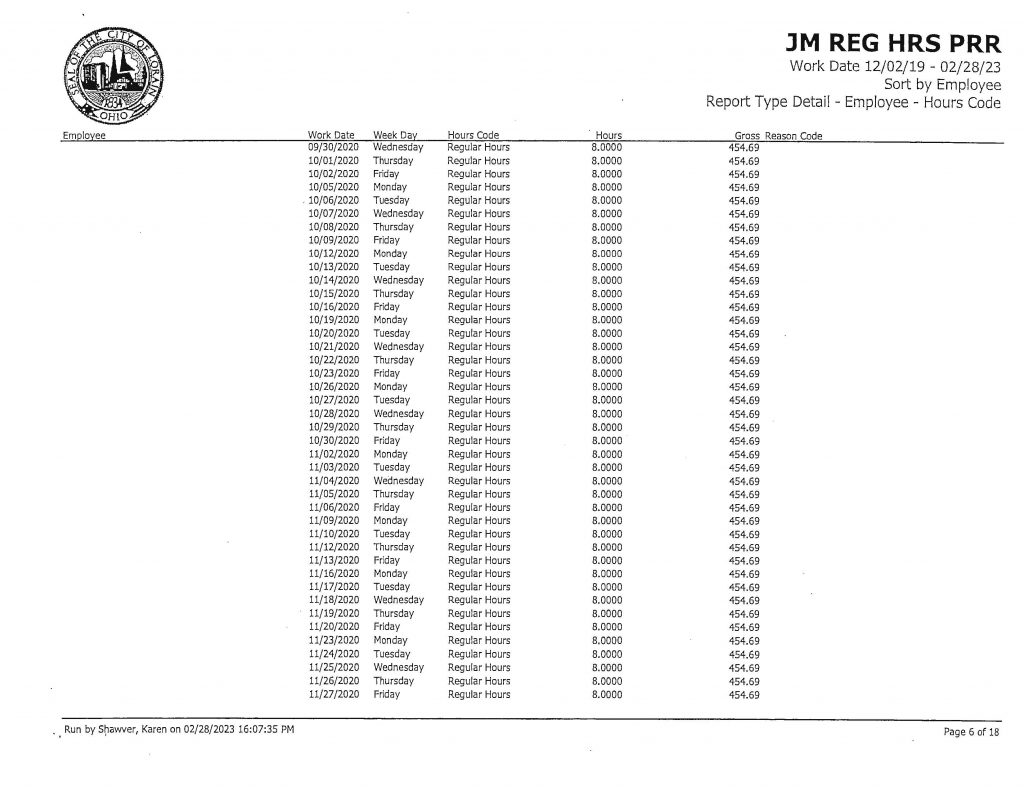

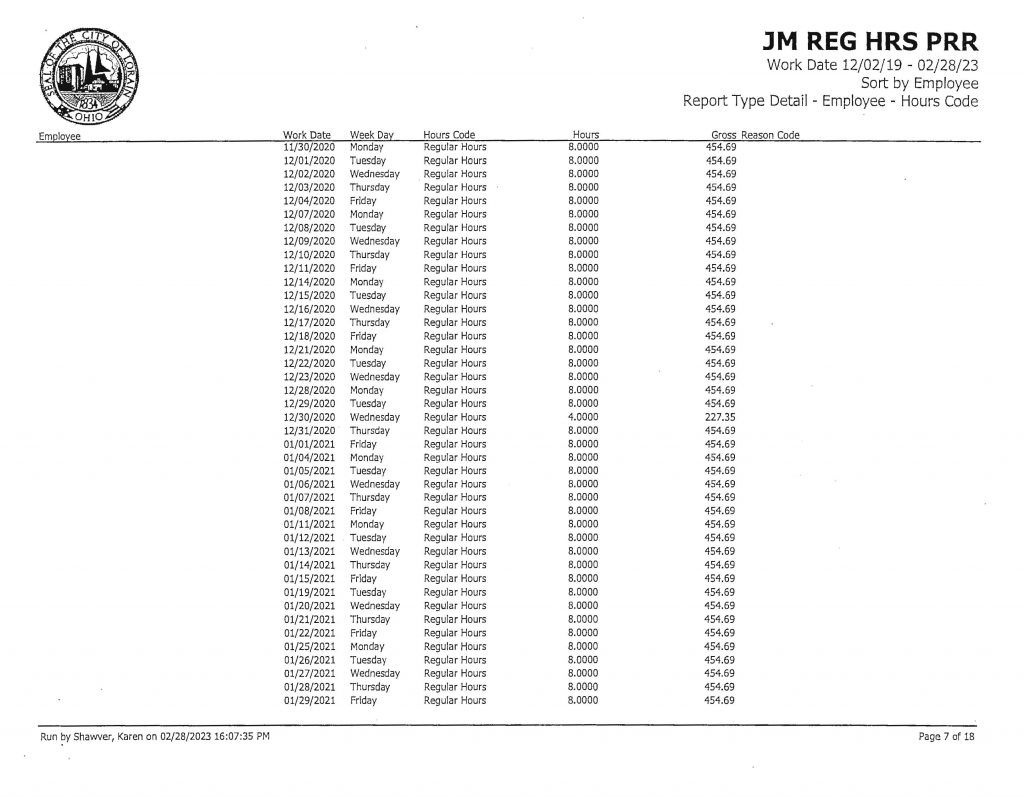

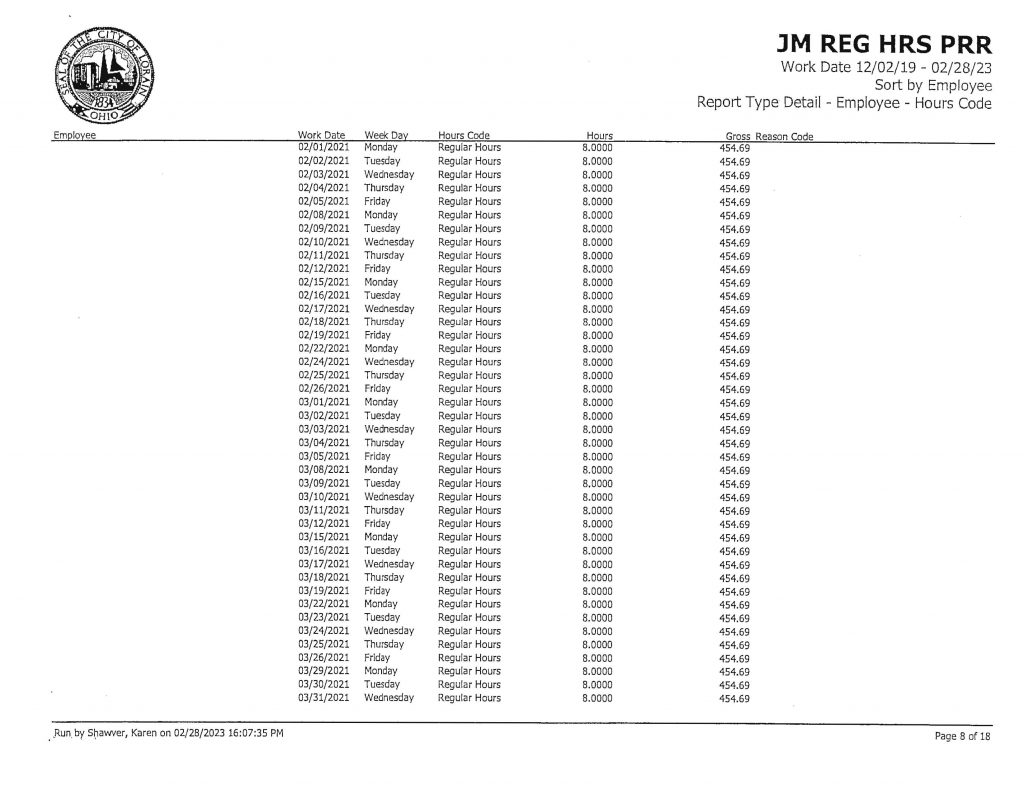

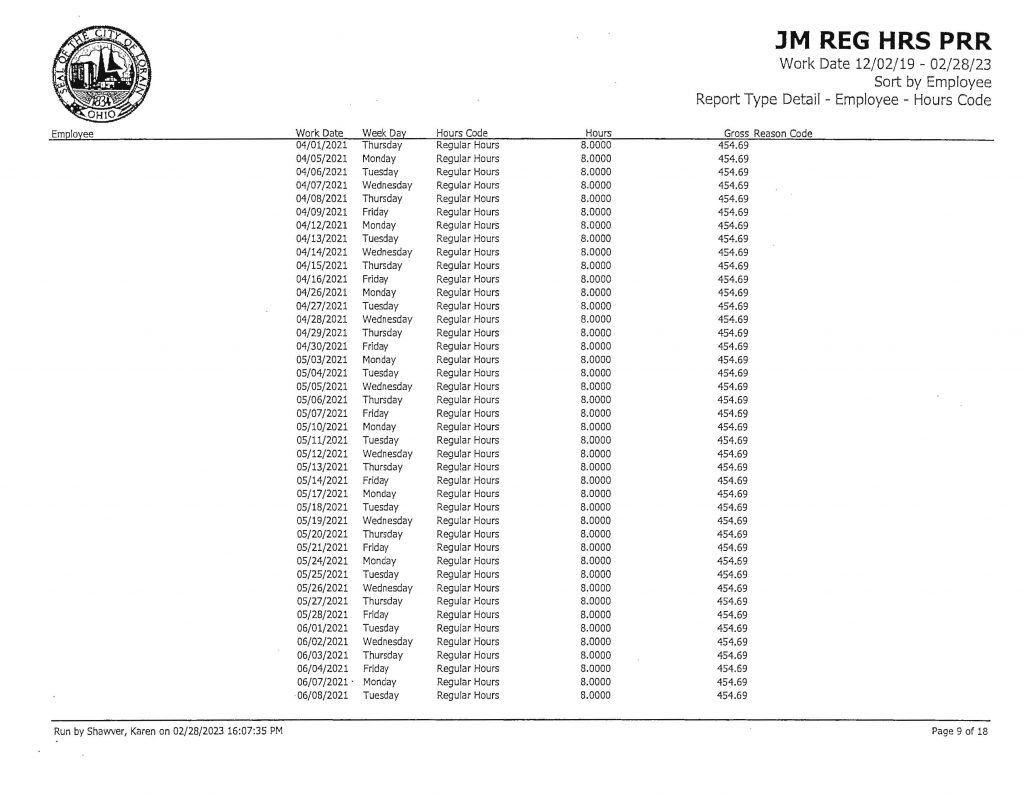

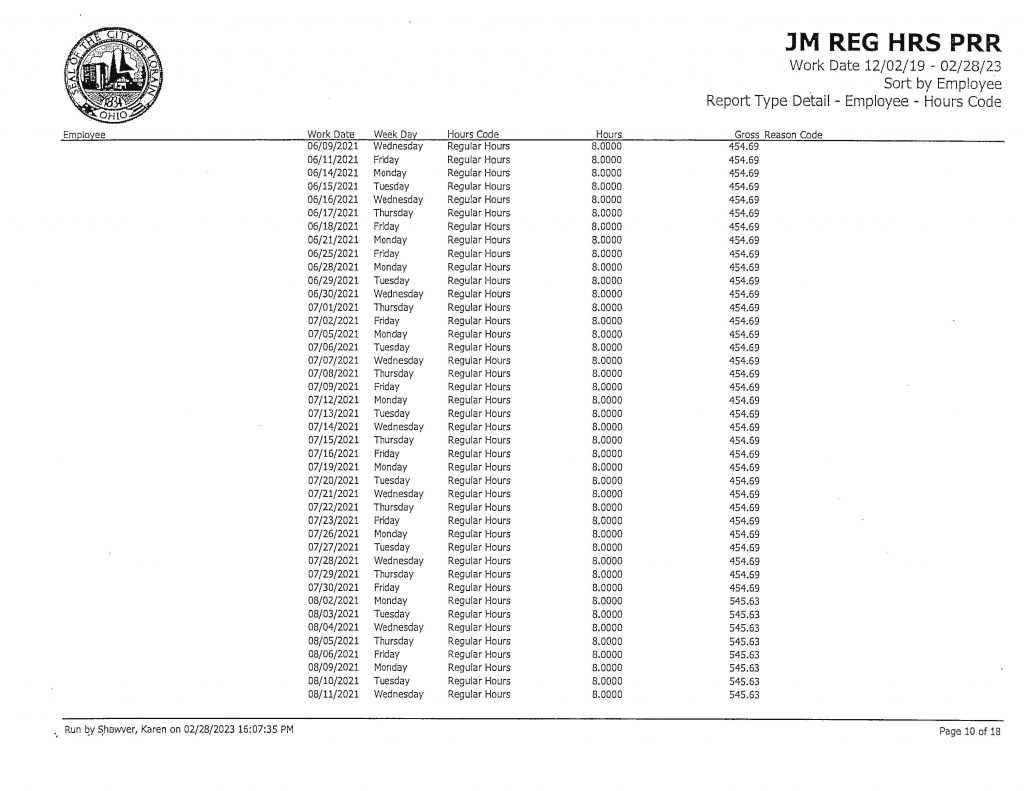

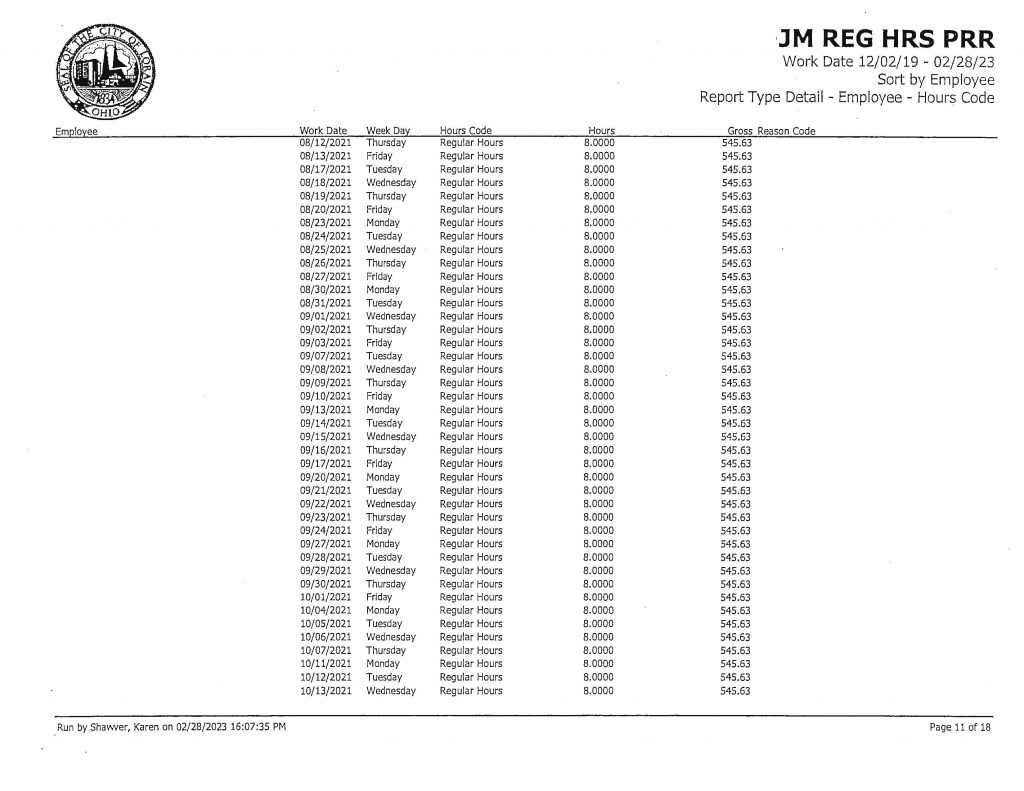

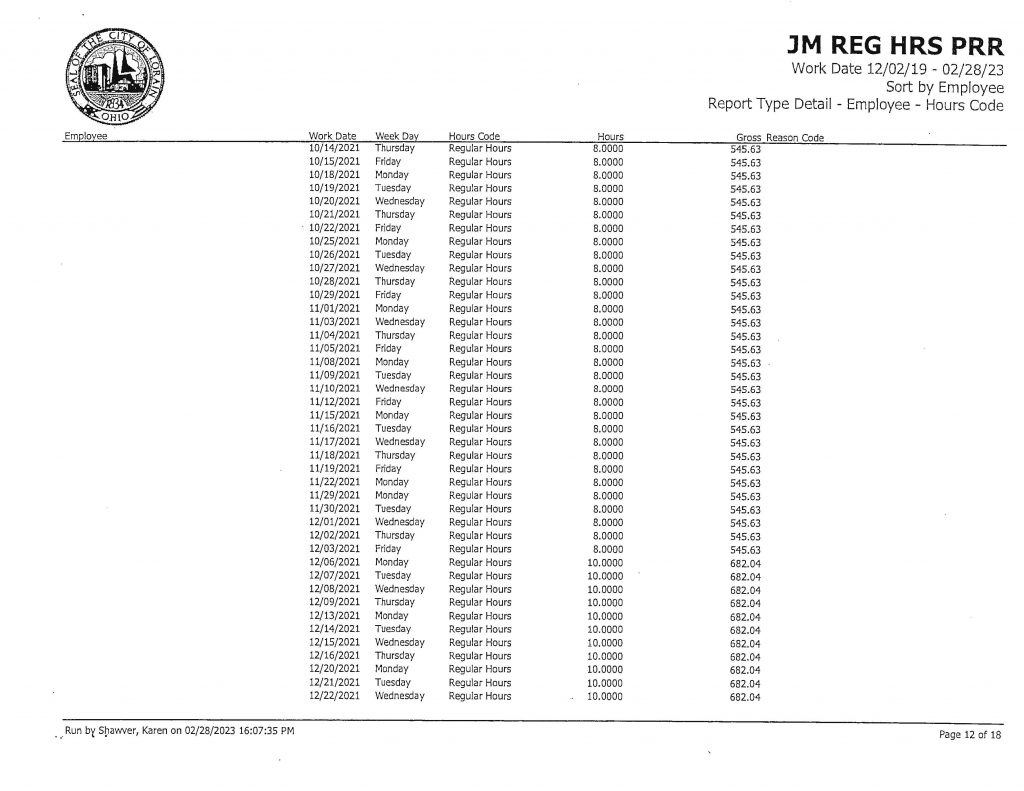

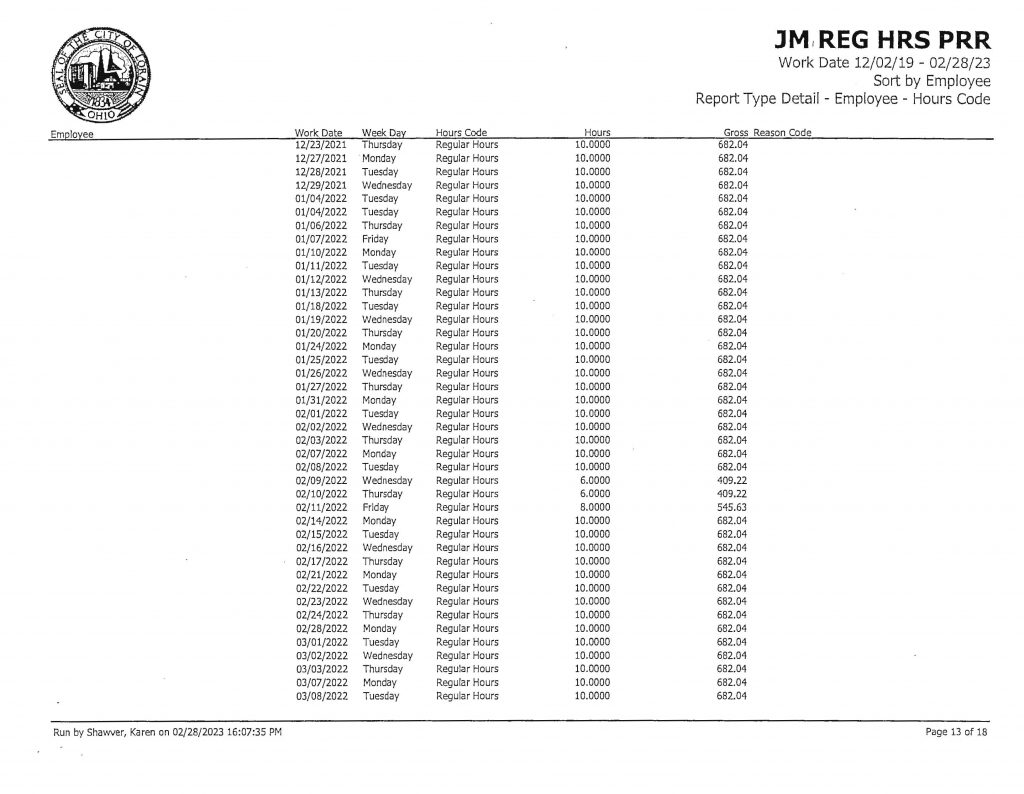

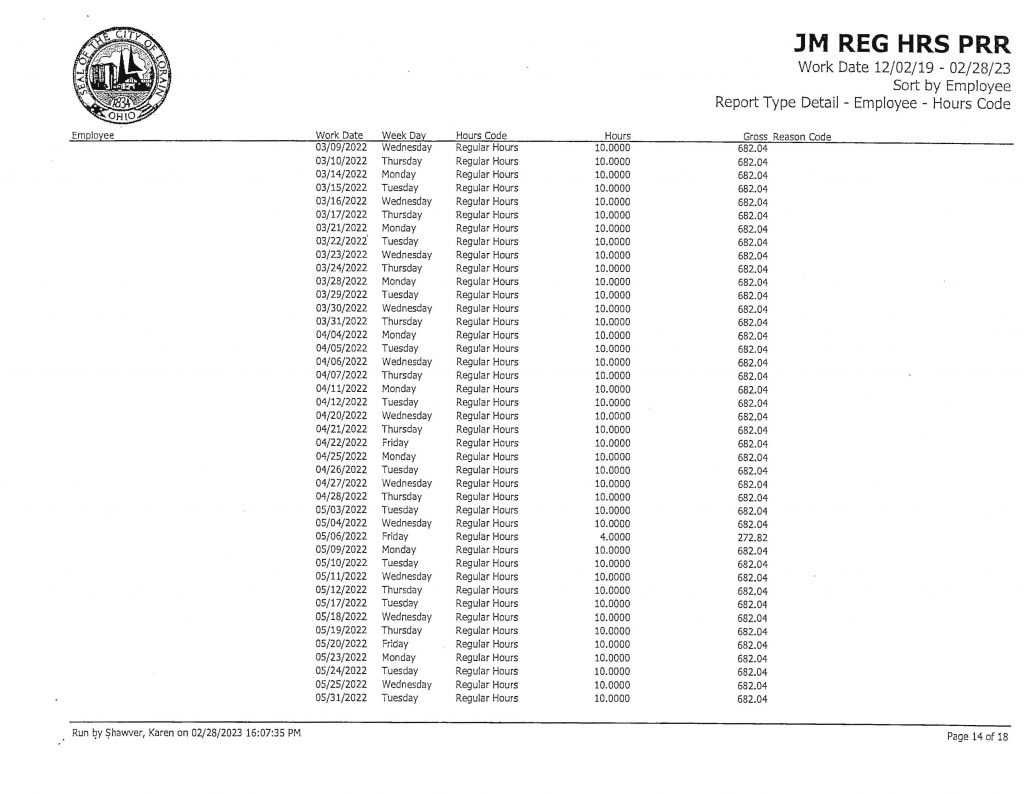

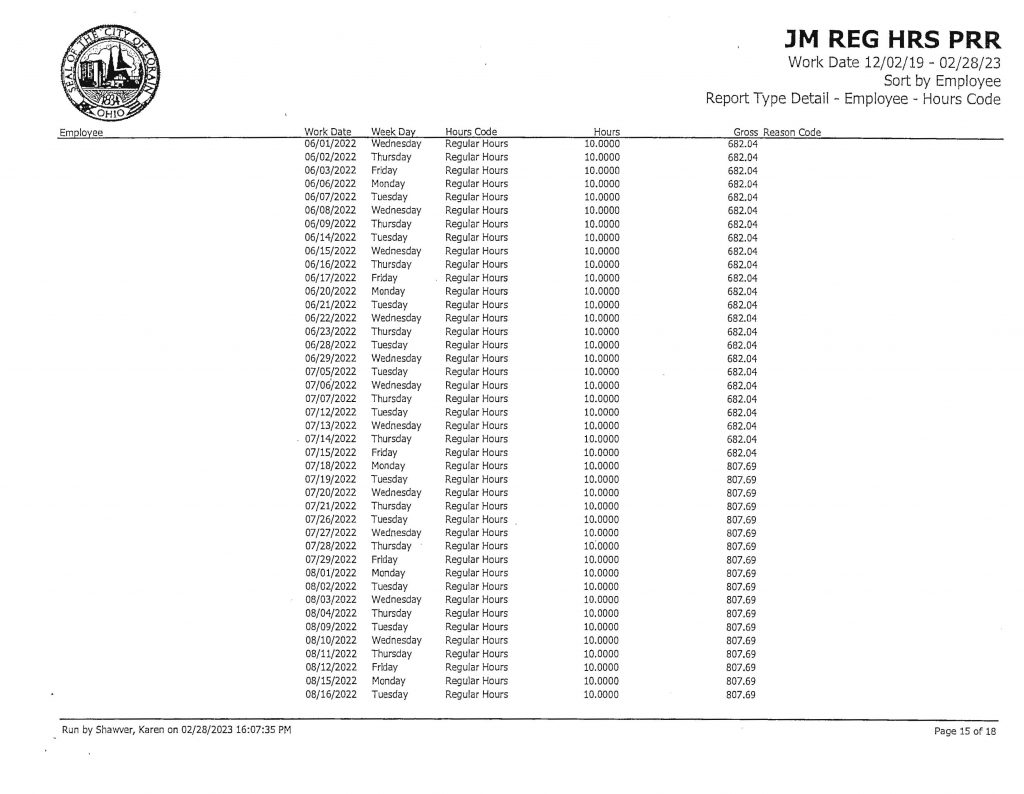

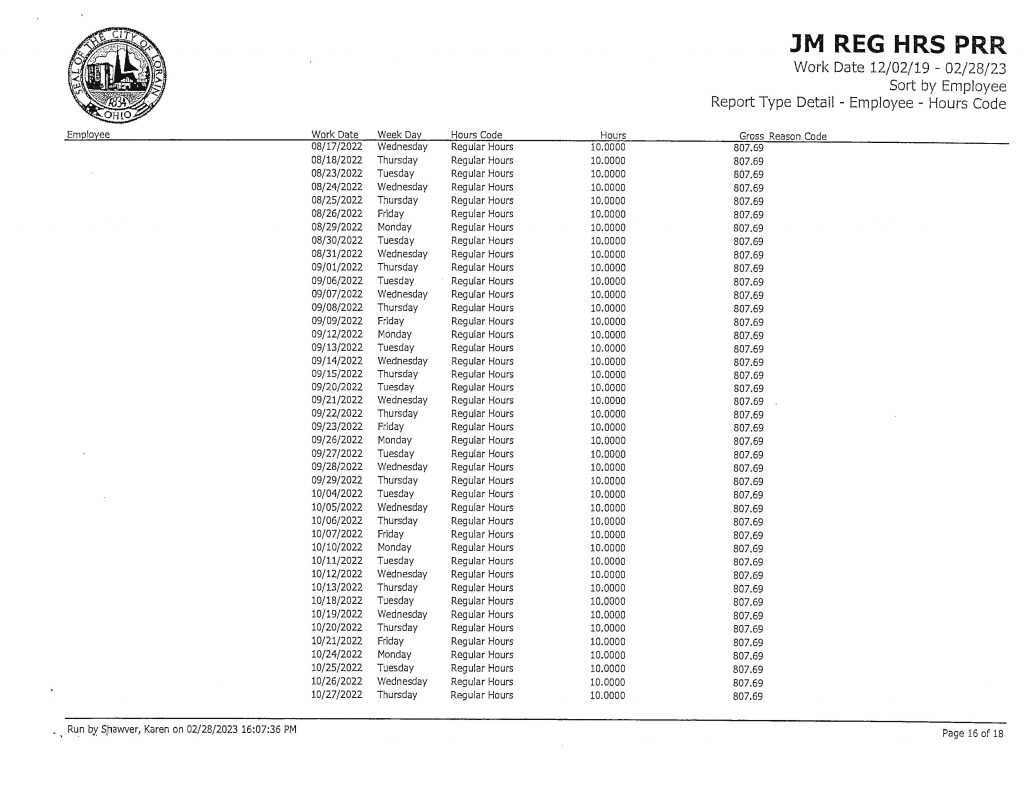

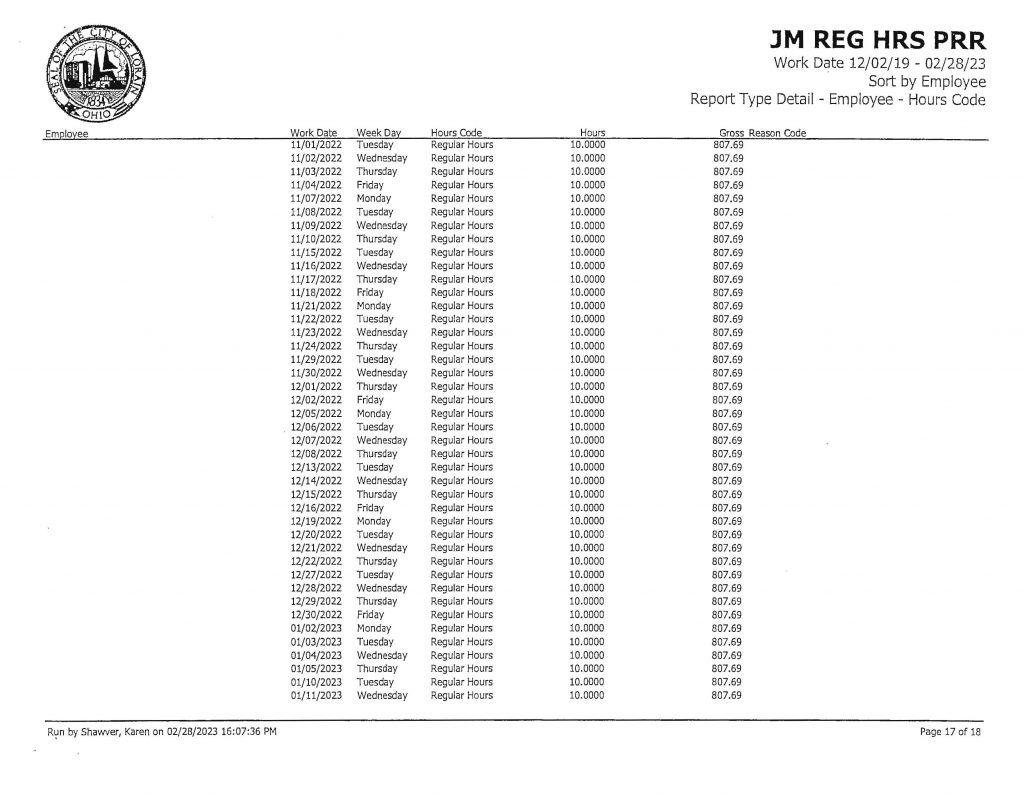

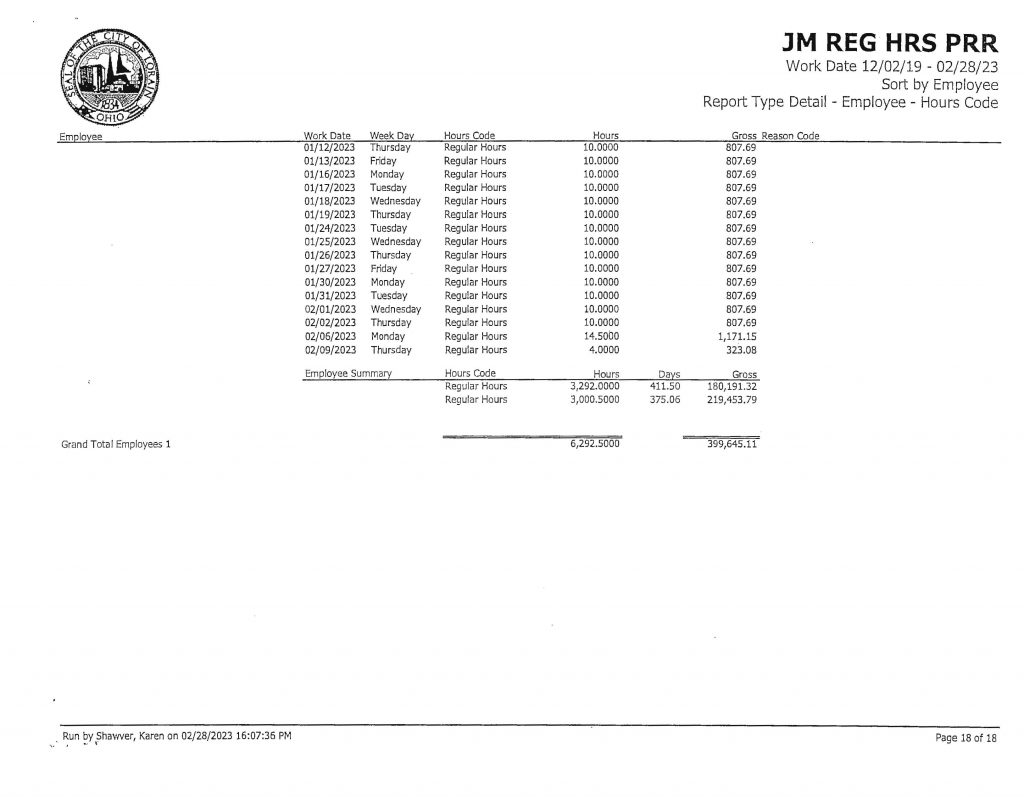

The packet at issue was not theoretical. It included printed payroll records generated from the City of Lorain payroll system, including “Higher Position” pay summaries for specific captains and detailed “Regular Hours” entries for the Chief of Police. Those records reflect date specific entries, hour codes, and gross pay amounts across dozens of individual work dates. For example, the payroll summaries show recurring entries coded “Higher Position” for Captains on dates where Chief James McCann is simultaneously reflected as receiving “Regular Hours” pay. The summaries culminate in a calculation identifying sixty eight total days in which a Captain received higher position pay while the Chief received regular pay.

mccann

Those are not casual notes. They are structured payroll documents with identifiable formatting, employee numbers, date ranges, and system generated headers such as “Run by Shawver, Karen on 02/28/2023” and “Work Date 12/02/19 – 02/28/23.” They are the type of documents that have evidentiary character precisely because of their format and source. A printed payroll record generated from an internal municipal system is not interchangeable with a later PDF attachment floating in email. The physical packet contains ordering, compilation decisions, and contextual presentation that are part of its identity.

Originals matter for authentication. Originals matter for chain of custody. Originals matter because an envelope with no return address, a typed explanatory letter, and a curated set of payroll exhibits constitute a single physical submission. The packet is a unit. Its contents are not merely informational. They are evidentiary. Agencies sometimes suggest that if a reporting party retains copies, then nothing is lost. That logic misunderstands the issue. Copies protect the reporting party from total loss. They do not relieve the receiving agency of its independent duty to log, preserve, and account for what it accepted. If an agency receives original physical documents during a scheduled meeting and later says “we have no record,” the existence of duplicate PDFs does not cure the institutional failure.

The response letter addresses this proactively and correctly:

“Copies are not substitutes for originals, and the presence of duplicates does not relieve a receiving agency of its duty to acknowledge receipt, maintain custody records, or accurately report what was provided.”

That statement reflects a basic principle of evidence integrity. When a law enforcement agency receives original materials, its obligation is not satisfied by later pointing to the fact that the reporting party also kept a copy. The obligation is to account for what came into its possession.

If the Sheriff’s Office ever attempts to pivot to “well you have copies,” the answer is straightforward. Copies preserve the whistleblower. Originals test the institution.

________________________________________

6. Why the Documents Matter, and Why “Salaried” Is Not a Complete Answer

The custody dispute is not happening in a vacuum. The documents at issue are not miscellaneous municipal paperwork or abstract allegations. They concern compensation practices inside a law enforcement agency, specifically the simultaneous recording of higher position pay for command staff and regular compensation entries for the Chief of Police on the same dates. That is not a casual administrative detail. That is structured payroll data generated in the ordinary course of government accounting.

The packet described in the response letter was not vague. It was not “concerns.” It was payroll and timekeeping records originating from the City of Lorain’s payroll system through the Auditor’s Office. The records reflected identifiable dates on which a Captain received higher position pay coded for acting chief duties. On those same dates, Chief James McCann was recorded as receiving full regular compensation with no leave time deducted. The County has already publicly acknowledged that these records were reviewed.

In reporting published by the Chronicle-Telegram and the Morning Journal, county officials stated that the payroll records were examined and that no wrongdoing was found because the Chief is a salaried employee. The public explanation, in substance, was that salaried status resolves the issue. But “salaried” is not a magic word that erases structure.

Salaried status explains how compensation is categorized. It does not automatically explain why higher position pay would be triggered for another command-level officer while the Chief simultaneously records full regular hours without leave adjustment. If the Chief was performing the duties of the office, the activation of acting chief compensation raises structural questions about why the payroll system reflected a higher position designation. If the Chief was not performing those duties on those dates, the absence of leave documentation becomes relevant.

The records do not accuse. They document. And that distinction matters.

All individuals referenced are presumed innocent of wrongdoing. The issue is not whether a newspaper article declared the matter resolved. The issue is whether the records themselves warranted structured intake, preservation, and accurate institutional accounting once they were physically delivered to command staff. The County’s public statement that the documents were reviewed and that no wrongdoing was found actually reinforces the custody problem. If the documents were reviewed, then they existed. If they existed and were evaluated, then they were received in some form. If they were received and discussed during a command-level meeting, then a later assertion of “no record” cannot be treated as a routine clerical response without explanation.

The documents were important enough to trigger review. They were important enough to produce a public conclusion. They were important enough to be referenced in press coverage. That makes the present denial posture something more than technical. When an agency both reviews documents and later asserts that it has no record of receiving the physical packet containing those documents, the issue shifts from payroll interpretation to institutional consistency. Salaried status may be part of the substantive analysis. It is not a substitute for chain of custody. It is not an explanation for why a physical packet delivered during a scheduled meeting would later disappear from institutional intake records. And it does not resolve the structural question now at the center of this dispute:

If the documents were important enough to review, how are they not important enough to log?

________________________________________

7. Authority and Institutional Risk

The response letter does more than catalog documents and dispute a denial. It raises a structural question that is often ignored until a controversy forces it into the open. Who has the authority to speak legally for a public office when allegations concern that office’s own conduct?

The correspondence from the Sheriff’s Office has come from an administrative official holding the title Director of Legal Affairs. That title may suggest legal authority. But titles do not determine delegated power. Public offices have designated legal counsel for a reason. Legal positions, litigation posture, conflict determinations, and referral decisions are not administrative housekeeping matters. They are legal acts with legal consequences. The response letter draws that distinction deliberately. It states that administrative correspondence does not transform an administrative official into legal counsel. It also makes clear that conditioning outside investigative referral on further submissions routed through a material participant is not neutral process management. It is control.

Authority matters because authority defines accountability.

When a public office responds to allegations about its own evidence handling by centralizing communication through a person who was present for the disputed events, who now speaks for the institution, and who attempts to condition referral to outside review, the structure itself becomes part of the story. Even if every individual involved believes they are acting appropriately, the architecture of the response matters. Public trust does not rest on internal assurances. It rests on process.

If the Sheriff’s Office has designated legal counsel of record, then legal determinations should come from that counsel. If a conflict exists, it should be formally evaluated and documented. If outside referral is appropriate, it should not require approval from the same office whose conduct is under scrutiny. When these lines blur, institutional risk increases.

The response letter captures that risk in a single sentence.

“Administrative correspondence does not confer authority, and it does not convert actions taken outside that authority into lawful ones.”

That is not rhetorical flourish. It is a warning about structure. In public institutions, actions taken without proper authority do not become valid because they are repeated. They do not become insulated because multiple officials echo the same position. And they do not become lawful because they are written on official letterhead. When serious allegations are routed through informal gatekeeping rather than clearly delegated legal channels, a closed loop forms. Closed loops protect participants. They do not protect public confidence. And once a closed loop is visible, it becomes part of the evidentiary landscape itself.

________________________________________

8. This Is Not Just a Records Dispute

When a law enforcement agency denies receipt of physical documents after an in person handoff to command level personnel, the issue cannot be reduced to filing systems or clerical oversight. This is not a misplaced memo. It is not a typo in a log. It is not an incomplete public records response. It is a question about custody, knowledge, and institutional truthfulness. Public institutions operate on documentation. When something is physically received, it is supposed to be logged. When it is logged, it can be traced. When it can be traced, it can be accounted for. That is the ordinary discipline of governance. The moment an agency moves from “we cannot locate it yet” to “we have no record it was ever received,” the analysis changes.

Depending on the surrounding facts, denial after receipt can implicate serious statutory concerns involving falsification, obstruction, dereliction of duty, or tampering with evidence. Raising those statutes is not an accusation. It is not a declaration of guilt. It is an acknowledgment that public officials operate within a legal framework where custody and truth are not optional. When an agency asserts a position that contradicts a documented physical transfer, that position carries legal significance whether the agency intends it to or not. Closure of an investigation does not erase statutory duties. It does not eliminate foreseeable proceedings. It does not convert prior receipt into nonexistence. It does not insulate an agency from scrutiny when its own evidence handling is called into question. In fact, closure can heighten risk. Once a matter is declared closed, subsequent disputes often arise in public records litigation, civil claims, oversight reviews, or professional accountability proceedings. At that point, the accuracy of what was logged and what was denied becomes more, not less, important.

This is why the “no record” posture matters.

If nothing was ever received, that should be demonstrable through internal calendars, intake logs, routing records, and contemporaneous communications. If something was received and mishandled, that is an internal control failure. If something was received and is now being affirmatively denied, that is an integrity problem. Those are not the same category of error. This dispute has crossed the line where it can be dismissed as administrative inconvenience. It now rests in the realm of institutional accountability, where custody, knowledge, and denial are not abstract concepts. They are legal facts.

9. The Two Plausible Explanations

At this stage, the range of plausible explanations is not wide. It is narrow.

Either the materials were received and were mishandled, meaning the failure lies in logging, routing, retention, or internal controls, or the materials were received and are now being affirmatively denied, meaning the failure lies in institutional integrity and truthfulness. There is no third option that preserves credibility while accounting for a physical, in person transfer to command level personnel.

This is not a scenario involving a vague recollection or an anonymous drop box. The delivery was described as deliberate, face to face, and observed. The participants have been identified. The contents have been described with specificity. The context of the meeting has been explained. Once those facts are on the table, institutional denial is no longer a neutral act. It is a position that requires explanation. If the Sheriff’s Office truly cannot locate the originals, then the proper response is not to shift the burden back to the reporting party or demand a new affidavit to reconstruct what should already exist in internal records. The proper response is to document the internal search process. Identify intake logs. Identify evidence control numbers, if any. Identify custodians. Identify routing protocols. Identify who had physical possession after the meeting and what was done next.

Transparency about the internal search would strengthen the agency’s position if this were truly a logging failure. Silence or continued reliance on “no record” without internal documentation does the opposite. And if the materials were received and are being affirmatively denied, that is not a paperwork problem. That is an integrity problem. Institutions recover from administrative mistakes. They do not recover easily from credibility collapses. The point is not to accuse. The point is to state plainly that the available explanations are limited. Accountability requires choosing one and documenting it.

________________________________________

10. What a Good Faith Office Would Do

A good faith office does not argue about recollection when it controls the records. It starts with its own systems.

It would identify the date of the meeting through internal calendars, scheduling software, visitor logs, and email confirmations. Command level meetings do not materialize from thin air. They are scheduled, noted, and attended. A neutral internal review would begin there. It would then determine whether an intake log, property receipt, routing slip, or evidence tracking entry exists. If such a log exists, it would be produced. If it does not exist, that absence would be acknowledged plainly, not obscured behind a generic phrase. Logging is not optional in law enforcement environments. It is foundational. It would identify who had physical custody of the materials immediately after the meeting. It would document whether the originals remain in the agency’s possession. If they do not, it would explain how they were transferred, to whom they were transferred, under what authority they were transferred, or whether they were returned, destroyed, or otherwise disposed of pursuant to policy.

It would document the internal search process in writing. Not as a rhetorical assurance, but as a procedural record. Who searched. What was searched. When it was searched. What was found. What was not found. That is how institutions demonstrate seriousness.Finally, if the delivery and subsequent denial involve individuals who were present at the meeting or who now speak on behalf of the agency, a good faith office would remove those individuals from the evaluation pathway and refer the matter to a genuinely independent reviewing authority. That referral would not be conditioned on additional submissions routed back through the same disputed channel. Independence cannot be pre-screened by a participant.Until that happens, the phrase “no record” should be understood for what it has become in this dispute. It is not merely a description of a filing outcome. It is a position taken by an institution in the face of a documented handoff. And positions can be tested.

Final Thought: Support, Disqualification, and What Comes Next

There is an irony at the center of this dispute that I cannot ignore. I did not approach the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office as an adversary. I approached it as someone who had previously provided support, advocacy, and even political assistance to the very officials who are now positioned against me.

I supported Sheriff Jack Hall publicly. I wrote letters. I helped craft statements. I lent my platform and credibility during an election cycle. That support was not symbolic. It was documented. It was real. It created a relationship that, at the time, was cooperative rather than hostile. The same administrative figure now responding in an official capacity was previously involved in correspondence connected to that political context. That history is not rumor. It is part of the institutional record.

Those facts matter because they dismantle the idea that this dispute is rooted in long standing animosity. If anything, the opposite is true. I once placed trust in these officials. I used my voice in support of Sheriff Hall. I did so because I believed in the office and believed in the importance of law enforcement accountability conducted properly. That is not the conduct of someone seeking to destabilize an institution. It is the conduct of someone who believed the institution deserved confidence. That prior support is also what sharpens the conflict issue. When I have engaged in political advocacy connected to a sitting sheriff, and when that same sheriff’s administrative leadership later becomes the subject of complaints I submit, ethical guardrails are not optional. They are required. Prior political alignment does not erase conflict concerns. It intensifies them. It requires distance and independent review, not consolidation of control inside the same circle.

My assertion that Sheriff Hall is conflicted is not based on speculation. It is based on documented prior interactions, political entanglements, and the existence of relationships that predate this dispute. When an office with that history undertakes to evaluate complaints brought by the same individual who previously supported it, neutrality cannot simply be assumed. It must be demonstrated. So far, it has not been.

Aaron C Knapp

Instead, the written record now reflects a collective denial. According to correspondence from the Sheriff’s Office, multiple senior officials state that they have “no record” of documents delivered during a command level meeting. That is not a narrow clerical response. It is an institutional position. And when multiple officials adopt the same denial posture in the face of a described in person handoff, the issue stops being about filing systems. It becomes about institutional credibility.

Let me be clear. All individuals referenced are presumed innocent of wrongdoing unless and until proven otherwise in a court of law. This reporting is for news, public accountability, and First Amendment purposes. It is not legal advice. Presumption of innocence is a cornerstone of justice. But it does not require the public to suspend scrutiny when contradictions appear in the official record. The deeper issue here is not simply whether a packet can be located. The deeper issue is what it means for a law enforcement agency to deny receipt after a documented delivery, in a context where prior political and professional entanglements already complicate neutrality. That combination does not build trust. It erodes it.

This is not the end of the story. It is a transition point.

The next piece will not focus on process, conflict, or denial posture. It will focus on the documents themselves. I will publish a detailed, document specific analysis of the payroll and timekeeping records that were delivered. I will explain what those records show, how acting chief compensation was recorded, how full regular hours were simultaneously entered, and why the public statement that the matter was reviewed and found to involve “no wrongdoing” because the Chief is salaried deserves closer examination. I will compare what was reported in local coverage to what the records actually reflect.

If the institutional response is “no record,” then the record I preserved will speak.

© Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All rights reserved.