When Innocence Is Declared Without the Evidence

A Response to the Framing of Chief McCann and the Limits of Institutional Journalism

By Aaron Christopher Knapp

Investigative Journalist and Government Accountability Reporter

Editor-in-Chief, Lorain Politics Unplugged

Licensed Social Worker (LSW), Ohio

Public Records Litigant and Research Analyst

Introduction: This Is Not Journalism, It Is Participation

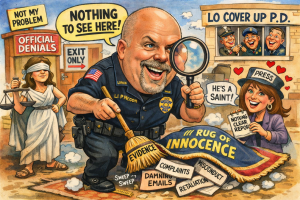

The problem with the article written by Heather Chapin is not that it reached a conclusion favorable to former Lorain Police Chief James McCann. Journalists are allowed to reach conclusions. The problem is that the conclusion was reached by someone who is not operating as a neutral observer at all, and who has previously inserted herself into the very narrative she now claims to evaluate from a distance.

This is the same Heather Chapin who, according to contemporaneous accounts and communications, relayed allegations to McCann asserting that I intended to harm Tia Hilton. Those allegations were false. They were not supported by evidence. They were not the product of a law enforcement finding. And yet they were passed along in a way that gave them institutional oxygen and personal consequence.

That matters. Not as a side note, but as a threshold issue of credibility.

A journalist who transmits unverified or false allegations about a subject to a police chief is no longer merely reporting on events. She is influencing them. She becomes a participant in the chain of action she later purports to analyze. And unlike me, who has repeatedly disclosed my role, my interests, and my stake in the matters I report on, Chapin does not acknowledge this involvement. She presents herself as neutral while having acted in ways that directly affected the people and institutions she now covers.

That is not an academic concern. It goes to the heart of whether the article can be trusted at all.

The article does not prove McCann’s innocence. It assumes it, then arranges the narrative to shield that assumption from scrutiny. This is not a semantic distinction. It is the difference between investigation and amplification, between journalism and reputation management.

When a story begins with the premise that a chief of police must be innocent because no criminal charges were filed, and then treats that absence of charges as affirmative proof, the analysis collapses under its own weight. Prosecutorial inaction is not exculpation. Silence is not clearance. Declination is not vindication. These are not controversial propositions. They are baseline principles in accountability reporting, especially when the subject of scrutiny is a powerful law enforcement official operating within a system that rarely charges its own.

What makes this failure more egregious is that it comes from a reporter who cannot plausibly claim detachment. A journalist who has previously relayed false allegations about a subject to the very official later defended in print is not standing outside the story. She is inside it. And when that involvement is not disclosed, the reader is misled about the frame through which the reporting is being done.

This is not about personal animus. It is about method and honesty. A reporter who influences the narrative behind the scenes and then publishes a piece declaring one side innocent without grappling with records, patterns, or contradictions is not performing journalism. She is laundering an institutional position through the credibility of her byline.

The article does not examine the documentary record. It does not interrogate policy. It does not engage the retaliation framework. It does not confront the contradictions between public denials and private communications. Instead, it relies on the absence of charges and the assurances of those in power, while ignoring the reporter’s own role in shaping the environment in which those assurances were made.

That is not neutrality. It is participation without disclosure.

And when journalism crosses that line, when it pretends to stand apart while actively shaping outcomes, the issue is no longer whether the conclusion is right or wrong. The issue is that the process is compromised. Readers are not being informed. They are being managed.

This kind of reporting does not merely fail to hold power accountable. It becomes part of the mechanism by which power avoids accountability. And calling that out is not hostility. It is the bare minimum required if the word journalism is to mean anything at all.

The False Equation Between “No Charges” and “No Misconduct”

The central analytical failure in the article is the lazy and indefensible equation of no criminal charges with no wrongdoing. That equation is not supported by law, it is not supported by journalism ethics, and it is flatly contradicted by historical reality. It is a rhetorical shortcut used when a writer either does not understand how power insulates itself or does not wish to confront that fact.

Police chiefs are rarely charged while in office. They are even more rarely charged when the alleged misconduct involves misuse of authority, retaliatory communications, off-the-books pressure, or coordination through informal channels that are designed precisely to avoid criminal exposure. Those cases do not disappear because the conduct is lawful. They disappear because criminal statutes are narrow, prosecutorial incentives are political, and proof burdens are intentionally high when the subject wears a badge and controls an institution.

Any journalist with even a passing familiarity with accountability reporting knows this. Declinations are common. Investigations quietly stall. Referrals die in drawers. Silence is the system working as designed, not evidence that nothing happened.

A competent investigative analysis therefore asks a different and far more important question. Not whether charges were filed, but whether the conduct alleged, when measured against departmental policy, professional ethics, constitutional constraints, and public records law, was lawful, appropriate, or defensible. That is the work. That is the analysis. And that is precisely the work that Heather Chapin refused to do.

Her article never asks whether the communications at issue were authorized. It never asks whether they violated policy. It never asks whether they chilled speech, interfered with employment, or crossed ethical boundaries. It never asks whether similar conduct would be tolerated if committed by a lower-ranking officer. It never examines the paper trail. It never applies a retaliation framework. Instead, it treats prosecutorial inertia as if it were a finding on the merits.

That is not scrutiny. It is abdication.

By substituting the absence of charges for analysis, the article does not inform readers about how power operates. It misleads them. It teaches the false lesson that misconduct only exists when a prosecutor announces it, that records do not matter if officials deny them, and that law enforcement leadership should be presumed clean unless convicted. That worldview is not journalism. It is institutional comfort masquerading as restraint.

The truth is simpler and far more damning. The absence of charges answers only one question: whether a prosecutor chose to act. It answers nothing about whether misconduct occurred. Treating it as proof of innocence is not just wrong. It is bullshit dressed up as reason.

Ignoring the Paper Trail While Quoting the Institution

Another fatal structural flaw in the article is its total dependence on institutional statements while deliberately refusing to confront the documentary record that contradicts them. This is not a subtle omission. It is the backbone of the piece.

Defenders of James McCann are quoted at length. Their denials are printed verbatim. Their explanations are treated as sufficient. What is conspicuously absent is any serious engagement with the emails, internal communications, timelines, or policy provisions that exist independently of anyone’s spin. The article substitutes voices of authority for evidence and calls that balance.

This is not a dispute over interpretations or opinions. It is a dispute over records. Records either exist or they do not. Emails were either sent or they were not. Communications either complied with policy or they did not. Journalism that refuses to grapple with those facts is not exercising judgment. It is avoiding it.

When a chief of police sends emails about a civilian to court administrators, discusses licensure, mental health, or employment status outside any formal investigatory channel, and those emails exist in writing, the story cannot simply end with “no wrongdoing was found.” Not unless the reporter has reviewed those communications, explained their context, analyzed their legality, and reconciled them with the department’s own policies and governing law.

That work was never done.

The article does not analyze the content of the communications. It does not quote from them. It does not contextualize them. It does not ask whether the chief had authority to engage in those discussions at all. It does not examine whether the subject matter exceeded the scope of any legitimate law enforcement function. It does not compare the conduct to departmental policy on confidentiality, retaliation, or external communications. It does not ask whether similar conduct by a rank-and-file officer would have been tolerated. It does not even acknowledge that these questions exist.

Instead, it reports that the institution says everything was appropriate and moves on.

That is not journalism. That is stenography.

A reporter does not discharge their duty by asking officials whether they broke the rules and then printing the answer. Institutions deny misconduct as a matter of course. That is not news. The role of journalism is to test those denials against the record, not to elevate them above it.

By ignoring the paper trail and privileging institutional assurances, the article reverses the proper hierarchy of evidence. Documents become irrelevant. Policies become optional. The record becomes subordinate to reputation management. Readers are left with the impression that nothing improper occurred, not because the evidence supports that conclusion, but because the evidence was never examined.

That choice is not neutral. It is protective.

When journalism treats records as disposable and denials as decisive, it stops being a check on power and becomes a conduit for it. And once that line is crossed, the article is no longer an analysis of misconduct. It is part of the mechanism by which misconduct is obscured.

The Absence of the Retaliation Framework

Perhaps the most consequential omission in the article is the complete failure to apply a retaliation framework, a failure so fundamental that it renders the analysis intellectually unserious from the outset. Retaliation by law enforcement almost never presents itself as a single dramatic event that announces its own illegitimacy. It does not usually arrive as an arrest without cause or a public threat. It arrives quietly, incrementally, and plausibly deniable, through a sequence of actions that are each framed as routine but collectively form a pattern of punishment.

Retaliation looks like emails that never should have been sent but were. It looks like complaints that did not need to be filed but suddenly were. It looks like records being shared outside proper channels, reputational information being circulated without necessity, and discretionary decisions being exercised in one direction and never the other. It looks like pressure applied through intermediaries, through institutions adjacent to law enforcement, through licensing bodies, courts, employers, and administrative processes that are insulated from public view. None of this is accidental, and none of it is visible if a reporter insists on examining each act in isolation.

A competent analysis therefore does not ask whether any single act, standing alone, could be explained away. It asks whether the same individual appears repeatedly at critical junctures. It asks whether the same tactics recur. It asks whether the timing of decisions aligns with protected activity, criticism, or reporting. It asks whether similar conduct has been directed at others who posed similar problems. It asks whether the pattern makes sense as coincidence or only as response.

The article does none of this. It atomizes the allegations, strips them of context, and then declares each fragment insufficient on its own. That approach is not neutral. It is structurally biased in favor of the person with power. Retaliation is designed to survive that kind of analysis. Anyone familiar with civil rights litigation, employment law, or police misconduct knows that patterns are the evidence. Intent is inferred from accumulation, not confession.

By refusing to zoom out, Heather Chapin ensures that retaliation cannot be seen even if it is present in plain view. The article never asks whether James McCann appears repeatedly across the communications, complaints, referrals, or institutional actions at issue. It never asks whether the same mechanisms were used more than once. It never asks whether the conduct escalated over time. It never asks whether the actions align with a known retaliation playbook that has been documented for decades in cases involving law enforcement critics and whistleblowers.

This is not a gap in detail. It is a refusal to apply the correct analytical lens.

An analysis that refuses to look for patterns cannot identify retaliation by design. It guarantees a predetermined outcome while maintaining the appearance of objectivity. That is why retaliation cases so often fail when examined superficially and succeed when examined holistically. The article chooses the former, not out of ignorance, but out of methodological choice.

In doing so, it strips the concept of retaliation of its meaning and replaces it with a caricature that requires a single overt act, an explicit admission, or a criminal charge. That is not how retaliation works, and pretending otherwise does not make the analysis cautious. It makes it dishonest.

When journalism declines to apply the very framework necessary to understand abuse of power, it is not merely incomplete. It is misleading. And when that choice consistently benefits the same actors, the omission stops being accidental and starts being explanatory.

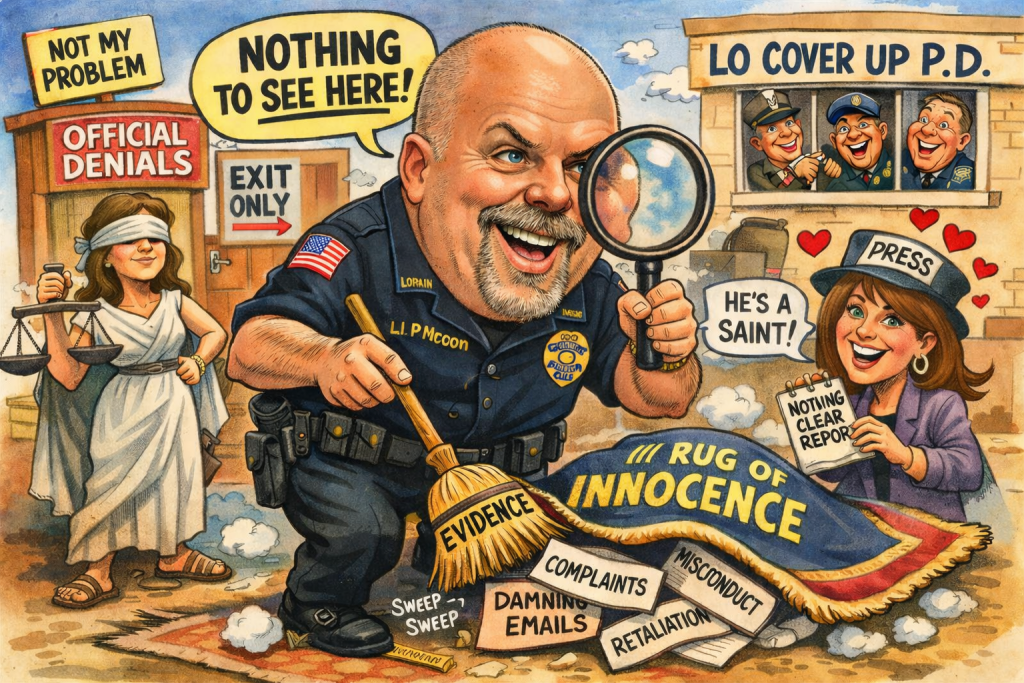

Treating Ethics as Optional Because Crime Is Hard to Prove

Another glaring analytical failure in the article is the implicit suggestion that if conduct is not criminal, it is therefore acceptable. That premise is not merely wrong. It is corrosive. It misunderstands how public service functions and it excuses precisely the kind of abuse that ethical frameworks exist to prevent.

Public officials, and police chiefs in particular, are not governed solely by the criminal code. They are bound by ethical standards, departmental policies, constitutional constraints, and public trust obligations that extend far beyond whether a prosecutor can prove a felony beyond a reasonable doubt. The criminal law sets the floor, not the ceiling. Treating it as the only relevant standard is how misconduct flourishes in plain sight.

A chief of police can violate policy without committing a crime. A chief can retaliate without satisfying the elements of a criminal statute. A chief can misuse authority in ways that are profoundly unlawful in civil or constitutional terms even if no handcuffs ever come out. That is not a loophole. It is a reality that anyone covering law enforcement is expected to understand.

Yet Heather Chapin collapses all of these distinctions into a single, lazy question: was he charged. When the answer is no, the inquiry stops. Policies are not examined. Ethics are not discussed. Constitutional implications are ignored. The analysis ends where it should begin.

This is not an innocent oversight. It is a deliberate narrowing of the frame that benefits the person with power. Criminal cases against police executives are rare not because misconduct is rare, but because the system is structurally disinclined to pursue them. Using that reality as proof of propriety is not caution. It is complicity.

The effect of this framing is to tell the public that unless a police chief is indicted, everything else is noise. Emails that should never have been sent become irrelevant. Conflicts of interest become technicalities. Retaliatory patterns become coincidences. Policy violations become misunderstandings. Ethics become optional.

That is not how accountability works. It is how it is avoided.

By reducing the question of conduct to the presence or absence of criminal charges, the article launders behavior that would be unacceptable if committed by anyone without a badge. It normalizes a two-tiered standard where power determines scrutiny and the lack of prosecution becomes a shield against all other forms of responsibility.

That framing does not just protect James McCann. It protects the system that allowed the conduct to go unexamined in the first place. And when journalism adopts that posture, it is no longer holding power to account. It is explaining away why power should not have to answer at all.

The Selective Use of Credibility

The article also exposes a deeply selective and fundamentally dishonest approach to credibility. Institutional actors are treated as reliable narrators by default. Their statements are accepted as sober, objective, and authoritative. Civilians and critics, by contrast, are treated as inherently suspect, emotional, or self interested, their accounts implicitly discounted unless they meet an impossible standard of perfection.

This asymmetry is not accidental, and it is not benign. When a police department speaks, it does so through layers of legal review, public information officers, and risk management strategy. Every word is vetted. Every denial is calculated. Every statement is crafted to minimize exposure. That is not a moral failing. It is how institutions protect themselves. But journalism that treats those statements as presumptively true while treating civilian accounts as presumptively unreliable is not exercising judgment. It is outsourcing credibility to power.

When a civilian speaks, especially one criticizing law enforcement leadership, they do so at personal risk. They risk retaliation, reputational harm, professional consequences, and legal exposure. They do not have counsel editing their emails or public relations staff shaping their narrative. They speak without institutional insulation. That imbalance should make journalists more skeptical of official statements, not less.

Yet in Heather Chapin’s analysis, the opposite occurs. Institutional denials are treated as clean and sufficient. Civilian allegations are framed as questionable unless they can clear a burden of proof that journalism itself refuses to undertake. Records are demanded from the critic but not from the institution. Consistency is demanded from the civilian but not from officials whose stories evolve behind closed doors.

This is not neutrality. It is protection.

A journalist who reflexively credits the institution while demanding flawlessness from the critic is not balancing perspectives. They are reinforcing a hierarchy of credibility in which power speaks truth by virtue of its position and dissent is suspect by virtue of its existence. That hierarchy is exactly what accountability journalism is supposed to dismantle.

The result is predictable. Official narratives harden into accepted fact. Civilian accounts are reduced to noise. Patterns of misconduct disappear because each individual voice is treated as unreliable in isolation. And the public is left with a distorted understanding of reality that favors those least in need of protection.

Credibility is not something that should be allocated based on title or uniform. It is something that must be earned through evidence, consistency, and transparency. When journalism abandons that principle and instead treats institutional authority as a proxy for truth, it does not merely fail to challenge power. It becomes one of the mechanisms through which power avoids being challenged at all.

What an Honest Analysis Would Have Required

A serious and honest analysis of James McCann’s conduct would have required an approach fundamentally different from the one taken. It would have started with the primary evidence, not the institutional talking points. That means examining the emails themselves, in full, with dates, recipients, context, and sequencing, rather than relying on paraphrased summaries or assurances from interested parties. Words matter. Who was contacted, what was said, why it was said, and whether it was authorized are not peripheral details. They are the substance of the inquiry.

An honest analysis would have then measured that conduct against the Lorain Police Department’s own policies, against generally accepted law enforcement standards, and against the constitutional and ethical constraints that govern the use of police authority. It would have asked whether the communications were within the scope of McCann’s role, whether they served a legitimate law enforcement purpose, and whether they respected the boundaries between policing, courts, licensing bodies, and civilian life. Policy exists precisely so that discretion does not become pretext. Ignoring policy while quoting officials about propriety is not analysis. It is avoidance.

A credible examination would also have acknowledged a basic reality that anyone who has ever covered civil rights, employment retaliation, or police misconduct understands. Retaliation does not require a criminal charge to be real. It does not require an indictment to be harmful. It does not require a prosecutor’s press release to exist. Retaliation is identified through patterns, timing, escalation, and misuse of authority, not through the narrow lens of criminal liability alone. Pretending otherwise is not caution. It is willful blindness.

An honest analysis would have asked why certain communications occurred at all. Why a police chief was discussing a civilian’s licensure, mental health, or employment status with court administrators. Why those discussions took place outside any transparent investigatory process. Why they coincided with criticism or protected activity. Why similar conduct appears in other contexts involving other critics. Those are not hostile questions. They are the minimum questions required when power is exercised behind closed doors.

Most importantly, an honest analysis would have resisted the reflexive urge to declare innocence simply because the system declined to act against one of its own. Systems routinely fail to discipline their leaders. Prosecutors routinely decline cases involving senior law enforcement officials. That reality is not controversial. Treating it as proof of propriety is not journalism. It is institutional deference masquerading as restraint.

What was required here was skepticism, rigor, and independence. What was delivered instead was a narrative that substituted official silence for scrutiny and treated inaction as vindication. That choice did not merely weaken the analysis. It defined it.

Conclusion: Innocence Is Not Proven by Silence, and Journalism Is Not Proven by a Byline

Heather Chapin’s article does not establish the innocence of James McCann. It establishes only that the institutions surrounding him declined to act in ways that would create criminal liability. That is not exoneration. It is institutional inertia. Confusing the two is not analysis. It is misrepresentation by omission.

More troubling, the article reveals nothing about what evidence Chapin actually reviewed before reaching her conclusion. Did she examine the emails themselves, in full and unredacted form. Did she obtain official reports rather than verbal summaries. Did she review internal policies, disciplinary standards, or communication rules. Did she request the records that would either corroborate or contradict the denials she printed. Or did she simply repeat the official narrative supplied to her and call that reporting.

Those questions are not rhetorical. They are the core of journalistic credibility. And they remain unanswered.

This is especially serious because Chapin is not a neutral observer parachuting into a complex dispute. She is the same reporter who previously relayed false allegations about my supposed intent to harm Tia Hilton to McCann, allegations that were unsupported, unverified, and demonstrably untrue. That act alone places her inside the chain of events she later purports to assess. A journalist who transmits false claims to law enforcement is no longer merely reporting. She is influencing outcomes.

What makes this indefensible is that Chapin does not disclose this involvement. She presents herself as detached, impartial, and authoritative, while failing to acknowledge her prior role in shaping the very narrative she now frames for the public. That is not transparency. It is concealment. And when a reporter conceals her own participation, the credibility of everything that follows collapses.

Journalism does not get to claim neutrality while acting as an intermediary for power. It does not get to launder institutional denials without interrogating the record. It does not get to declare innocence by default while ignoring documentary evidence that raises serious questions about misuse of authority, retaliation, and ethical violations.

And this failure does not belong to Chapin alone.

Her editor, Darrell Tucker, bears responsibility for allowing this article to go into print without demanding answers to the most basic editorial questions. What documents did the reporter review. What records were requested and denied. What evidence contradicts the official statements being quoted. What conflicts of interest exist. What facts are missing. An editor’s job is not to smooth prose or manage deadlines. It is to prevent exactly this kind of institutional regurgitation from being mistaken for reporting.

By publishing an article that treats the absence of charges as proof of propriety, that elevates official denials over documentary records, and that fails to disclose the reporter’s own prior involvement, the publication did not inform the public. It misled it.

The opposite story is not that James McCann is guilty. That question requires evidence, process, and scrutiny. The opposite story is that the question was never honestly examined at all.

When journalism treats silence as vindication, when it substitutes access for analysis and denials for documentation, it abdicates its role. It stops being a check on power and becomes a mechanism through which power protects itself.

In a system built on public trust, that is not a minor failure. It is the most dangerous outcome of all.

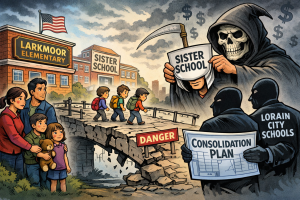

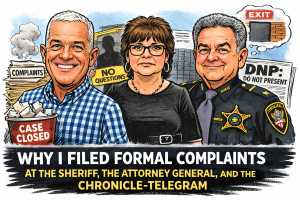

The Unanswered Conflicts Inside the Sheriff’s Office

Separate from the failures of journalism and institutional silence surrounding James McCann, there is a second, equally troubling layer of this story that has received virtually no public scrutiny. That layer concerns the conduct of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office itself, and its decision to insert itself into matters involving my complaints despite glaring and documented conflicts of interest.

In a formal written demand, I requested a complete explanation of why the Sheriff’s Office undertook, or attempted to undertake, any investigative involvement related to my complaints when clear conflicts existed involving Sheriff Jack Hall and an attorney referred to here as Nici, both of whom had prior political and professional entanglements directly connected to me. Those conflicts were not hypothetical. They were known, documented, and unavoidable.

At the center of the request is the basic principle that law enforcement agencies do not get to police matters in which their leadership has a personal, political, or adversarial stake. Under accepted ethical standards and long-standing conflict-of-interest principles, the proper response in such circumstances is recusal and referral to a neutral outside agency. That did not occur here. Instead, the Sheriff’s Office involved itself without publicly articulating any legal or policy justification for doing so.

The conflict involving Sheriff Hall is straightforward. There is a documented history of conflict between us. That alone should have disqualified the Sheriff’s Office from exercising discretion over any complaint connected to me. Yet no explanation has been provided identifying what statute, internal policy, or directive justified continued involvement rather than referral to an outside authority such as the Bureau of Criminal Investigation or the Ohio Attorney General’s Office.

The involvement of the attorney known as Anthony Nici deepens the problem. Nici is a licensed attorney subject to the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct. He previously authored letters for me in support of Sheriff Hall during an election, creating a clear political and professional entanglement. More troubling, he later drafted a letter that was sent to me through Sheriff Hall and asked that I submit it myself, a maneuver that appears designed to obscure authorship and route an election-related challenge through my name. That conduct raises serious ethical concerns that go well beyond politics and squarely implicate professional responsibility.

Any participation by an attorney with that history in the review, evaluation, or influence of an investigation touching the same parties is a textbook conflict of interest. Yet the Sheriff’s Office has never explained why that conflict was ignored, who authorized continued involvement, or what safeguards, if any, were put in place to prevent bias or improper influence.

Compounding these concerns is the unexplained dismissal of a packet of evidence I submitted to the Sheriff’s Office. That packet originated from a high-ranking law enforcement officer and contained detailed, professionally prepared documentation supporting my complaints. Despite the credibility of the source and the completeness of the material, the Sheriff’s Office concluded that the evidence was insufficient or did not merit further action. No meaningful follow-up occurred.

In response, I requested a written explanation detailing how the evidence was evaluated, who reviewed it, what standards were applied, why such comprehensive documentation was dismissed, what follow-up steps were taken, and whether the outcome was influenced by the fact that I was the complainant. To date, no transparent explanation has been provided. The appearance created is difficult to avoid. The matter appears to have been dismissed not because of the evidence, but because of who submitted it.

Finally, I formally demanded the return of all original materials I provided to the Sheriff’s Office, including documents, letters, audio, digital files, and any other evidence in its possession. That demand was made in anticipation of seeking outside investigations, particularly in light of additional evidence reflecting personal familiarity between Sheriff Hall and James McCann, including photographs showing them socializing together. At that point, continued internal handling was no longer merely questionable. It was indefensible.

What remains most striking is not that these questions were asked. It is that they remain unanswered. No conflict-of-interest review has been disclosed. No legal basis for jurisdiction has been articulated. No record of referral to a neutral agency has been produced. No explanation for the dismissal of evidence has been given. Silence has been substituted for accountability, once again.

In a system that depends on public trust, that silence is not neutral. It is explanatory.

How the Sheriff’s Office Conduct Fits the McCann Retaliation Pattern

The conduct of the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office does not exist in isolation. It mirrors, reinforces, and extends the same retaliation dynamics present in the McCann matter, which is precisely why it cannot be dismissed as a separate or unrelated controversy.

Retaliation by law enforcement rarely takes the form of a single overt act. It is almost always structural. It functions through discretionary decisions that appear neutral on the surface but are applied selectively, inconsistently, or without explanation when the subject is a critic, complainant, or perceived adversary. In the McCann context, that pattern is visible through informal communications, off-channel information sharing, and the use of institutional authority in ways that fall outside ordinary process while remaining insulated from criminal scrutiny.

The Sheriff’s Office involvement follows that same script. Rather than recusing from a matter involving known conflicts, the Office retained discretionary control. Rather than referring the complaints to a neutral agency, it kept the matter internal. Rather than transparently documenting how evidence was reviewed, it dismissed a professionally prepared evidentiary packet without explanation. Each of those choices, standing alone, can be framed as routine. Viewed together, they form a familiar pattern of containment.

This is how retaliation scales. When one agency’s conduct generates scrutiny, adjacent institutions step in not to investigate rigorously, but to absorb pressure, diffuse accountability, and provide procedural cover. The dismissal of evidence, the refusal to articulate jurisdiction, and the absence of a conflict-of-interest review do not interrupt the McCann retaliation framework. They continue it.

What matters is not whether the Sheriff’s Office explicitly coordinated with McCann. Retaliation does not require a meeting of the minds. It requires aligned incentives and shared institutional culture. The result here is the same. A complainant is isolated. Evidence is neutralized. Oversight is avoided. And the appearance of legitimacy is maintained through silence.

That is not coincidence. It is how retaliation survives without ever announcing itself.

The Ethical and Conflict-of-Interest Standards That Were Ignored

Ohio law does not require proof of a crime before ethical obligations attach. Public officials and attorneys are governed by overlapping but distinct standards designed to prevent exactly the type of entanglement present here.

For law enforcement leadership, accepted conflict-of-interest principles require recusal when personal, political, or adversarial relationships create even the appearance of bias. Ohio ethics guidance has long recognized that public confidence is undermined not only by actual impropriety, but by situations in which discretion is exercised by someone with a stake in the outcome. When such conflicts exist, referral to a neutral outside agency is the standard corrective measure. That step was not taken.

For attorneys, the obligations are even clearer. Under the Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct, a lawyer may not participate in matters where personal interests, former representations, or political entanglements materially limit professional judgment. Conflicts are not cured by silence, nor by routing actions through intermediaries. They are addressed through disclosure, withdrawal, or refusal to participate. When an attorney drafts or influences communications tied to an election, then later becomes connected to the handling of complaints involving the same individuals, the ethical problem is not subtle. It is structural.

The situation described here implicates both sets of standards. A sheriff with a documented adversarial relationship retains control over a matter instead of recusing. An attorney with prior political and professional involvement becomes entangled in subsequent actions affecting the same parties. Evidence from a high-ranking law enforcement source is dismissed without explanation. At no point is there a documented conflict review, a written justification for jurisdiction, or a referral to a neutral authority.

None of this requires speculation about intent. Ethics law does not turn on whether someone meant to act improperly. It turns on whether the safeguards designed to prevent bias were followed. Here, they were not.

Why This Matters

This matters because retaliation does not need to be criminal to be real, and conflicts of interest do not need to be proven in court to corrode public trust. What is being documented is not a technical dispute over procedure. It is a pattern of institutional behavior that consistently places discretion in the hands of conflicted actors, dismisses inconvenient evidence, and substitutes silence for explanation.

When journalism fails to interrogate this pattern, and when institutions refuse to explain their choices, the public is left with a dangerous fiction. The fiction that nothing happened because no one was charged. The fiction that evidence was fairly considered because no one admits otherwise. The fiction that accountability exists because the process claims to have worked.

But process without transparency is not accountability. It is insulation.

The McCann matter and the Sheriff’s Office conduct converge on the same conclusion. The system did not examine itself honestly, and it relied on the assumption that most people would not notice. The fact that these questions have been asked, documented, and left unanswered is not a side issue. It is the story.

And until those answers are provided, silence will continue to speak louder than any denial.

Final Thought: Accountability Does Not Belong to the Powerful

At some point, the conversation has to move past politeness and into honesty. What has unfolded here is not a disagreement about tone, or style, or even conclusions. It is a failure of accountability involving people who know better and institutions that benefit from pretending otherwise. The only reason this critique exists in the realm of journalism rather than litigation is simple and narrow. My name was deliberately kept out of the article. That omission is the sole reason I am not suing. It is not a badge of restraint on the part of the reporter. It is a tactical boundary that avoided legal exposure while leaving the underlying failures untouched.

When Heather Chapin chose to frame the absence of criminal charges as proof of innocence, she did not merely take a position. She adopted the most protective possible posture toward power while declining to interrogate the record that contradicts it. That choice matters. Journalism is not obligated to accuse, but it is obligated to examine. When a reporter accepts official narratives at face value in cases involving law enforcement retaliation, selective enforcement, or misuse of authority, the result is not balance. It is insulation. It is the conversion of access into authority and silence into vindication.

The same is true for James McCann, whose conduct has repeatedly been defended not through transparent engagement with documentary evidence, but through institutional silence and procedural evasion. Innocence is not established by attrition. It is established by confronting facts, policies, timelines, and contradictions head on. When those are avoided, credibility erodes whether a courtroom is involved or not. Institutions do not earn trust by waiting out criticism. They earn it by answering it.

And then there is Jack Hall, whose actions, as reflected in the record, illustrate a deeper and more corrosive problem. One cannot invoke law enforcement status to gain eligibility, authority, or political advantage, while simultaneously disavowing involvement when that same status creates accountability. Public office does not permit selective identity. You do not get to be a law enforcement officer when it helps you and a private actor when it does not. Authority is not a costume that can be put on and taken off to suit convenience.

The involvement of an attorney, Nici, only sharpens the concern. Lawyers are not neutral scribes. They are trained professionals bound by rules that exist precisely to prevent authorship manipulation, misattribution, and process gaming. When a lawyer participates in conduct that obscures authorship or routes political challenges through another person’s name, that is not clever strategy. It is a breakdown of professional boundaries that demands scrutiny, not spin.

What ties all of this together is not conspiracy. It is culture. A culture in which law enforcement closes ranks, journalism defers to authority, and ethical lines are treated as optional when the right people are involved. A culture in which the absence of charges is treated as absolution and the presence of records is treated as inconvenient. A culture that depends on quiet, on omission, and on the hope that no one will insist on seeing what actually exists on paper.

That culture survives only when people are quiet. It survives when reporters do not ask what documents were reviewed, when editors do not demand to see the records, and when institutions learn that silence will be mistaken for innocence. It survives when accountability is treated as aggression and scrutiny as bias.

The reason this matters is not personal. It is structural. When journalists fail to interrogate power, when lawyers forget their obligations, and when law enforcement treats accountability as a threat rather than a duty, the public loses the ability to trust any of it. Not because everyone is corrupt, but because too many people are protected from being questioned. Trust collapses not from scandal alone, but from the repeated experience of watching serious questions go unanswered.

This is not a call for prosecution. It is a call for honesty. It is a demand that facts be addressed rather than waved away. It is a reminder that public office is not a shield and journalism is not supposed to be a comfort blanket for institutions that refuse to explain themselves. Leaving a name out of a story may avoid a lawsuit. It does not cure a failure of method.

The bad actors here are not defined by guilt or innocence. They are defined by choices. Choices to avoid transparency. Choices to rely on silence. Choices to protect reputations instead of confronting records. And those choices deserve to be named, examined, and remembered, because accountability does not belong to the powerful. It belongs to the public.

Addendum

Was My Name Released as the “Victim” in the Sheriff’s Office Complaint and Why That Matters

The short answer, based on the text of the Chronicle-Telegram article and the structure of the Sheriff’s Office findings it summarizes, is yes. My name was affirmatively released and publicly identified in connection with the final set of allegations reviewed by the Lorain County Sheriff’s Office, even though the Sheriff’s Office declined to characterize me as a crime victim in any formal charging sense. That distinction is not semantic. It is legally and ethically significant.

What occurred here was not the anonymous reporting of a generalized allegation. The article explicitly states that “the final set of allegations against McCann included a series of complaints submitted by Lorain resident Aaron Knapp.” That sentence does two things at once. It identifies the complainant by full name and residence, and it situates those complaints within a criminal investigative review conducted by the Sheriff’s Office and forwarded to the Prosecutor’s Office. In ordinary public understanding, that places the named individual in the role of reporting party and alleged victim, even if the investigating agency ultimately concludes that no criminal elements were met.

How Identification Occurred and Why It Is Not Neutral

The Sheriff’s Office report, as summarized, did not treat the complaints attributed to me as abstract or hypothetical. They were framed as a “final set of allegations” reviewed alongside claims of fraud, threats, and improper conduct by a sitting police chief. By naming me in that context, the reporting converted a set of documented complaints into a publicly attributed investigative outcome tied to my identity.

This matters because Ohio public records law and Ohio criminal procedure draw an important distinction between records of investigation and the discretionary publication of complainant identities. Nothing in Ohio Revised Code 149.43 requires a law enforcement agency or a media outlet to publish the name of a complainant when no charges are filed, particularly when the underlying conduct alleged includes retaliation, harassment, or intimidation by law enforcement officers. Disclosure is permitted, but permission is not obligation. Editorial discretion still exists, and so does ethical responsibility.

The result here is that my name was released not as a neutral witness, not as a third party, but as the identifiable source of allegations that the Sheriff’s Office then characterized as not meeting criminal elements. That framing, when paired with naming, predictably carries reputational consequences. It invites the reader to associate the complainant with claims deemed unsupported, without providing the underlying documentary record, the full statutory analysis, or the civil and constitutional standards that govern retaliation, public records obstruction, and abuse of authority.

Victim, Complainant, and the Legal Disconnect

It is also important to be precise about what the Sheriff’s Office did and did not decide. The report did not make a judicial finding. It did not adjudicate credibility under oath. It did not apply civil standards such as preponderance of the evidence, nor did it address constitutional retaliation under the First Amendment or Ohio’s Public Records Act. It assessed whether criminal intent could be established beyond a reasonable doubt.

Under Ohio law, a person can be a victim of unlawful retaliation, intimidation, or misuse of authority without the conduct rising to the level of a prosecutable criminal offense. That distinction is foundational. Criminal declination does not negate harm, does not resolve civil liability, and does not retroactively justify the conduct complained of. Yet by naming me and immediately pairing that identification with the phrase “did not meet the elements of criminal intent,” the reporting collapses those categories in the public mind.

Why the Disclosure Raises Broader Accountability Concerns

There is an additional and uncomfortable asymmetry in how disclosure was handled. The article relies heavily on a Sheriff’s Office report that is not quoted in full, not linked, and not independently published for public inspection. The reader is asked to accept summarized conclusions while the named complainant is exposed to scrutiny without the benefit of the underlying evidentiary record being made equally accessible.

That imbalance is not accidental. It mirrors a broader pattern in which government agencies selectively disclose conclusions while withholding primary records, and media outlets repeat those conclusions while naming private citizens who challenged official conduct. In that dynamic, the state retains institutional credibility while the complainant bears the reputational risk.

Why This Addendum Belongs in the Story

This clarification is not about disputing the Sheriff’s Office’s authority to investigate or the Prosecutor’s discretion not to charge. It is about accuracy, context, and accountability. My name was released in connection with a criminal investigative summary that rejected criminal charges, without a parallel explanation of the noncriminal legal frameworks under which my complaints were made and remain viable.

Readers deserve to understand that distinction. They deserve to know that being named in such a report does not equate to having filed false claims, nor does it resolve questions of retaliation, public records interference, or constitutional violations. And they deserve to know that the decision to name a complainant is itself a consequential act, one that should be examined with the same scrutiny applied to the conduct of the officials involved.

This addendum exists to make that clear, on the record, and without euphemism.

Editorial and Legal Disclosure

This article is an investigative opinion and accountability analysis based on public records, contemporaneous communications, documented timelines, and the author’s direct involvement in matters of public concern. Statements of fact are drawn from records in the author’s possession, records produced through public records requests, sworn statements, or from the absence of evidence where such evidence would reasonably be expected to exist.

Nothing in this article constitutes legal advice, nor is it intended to substitute for findings by a court of law, a disciplinary authority, or a prosecutorial agency. References to retaliation, misconduct, ethical violations, or abuse of authority are used in their commonly understood civil, ethical, and journalistic sense, not as declarations of criminal guilt.

Individuals and institutions named in this article are discussed in connection with their public roles, public conduct, or documented involvement in matters of public interest. Allegations are characterized as such. Conclusions are drawn from the available record, the content of disclosed documents, and the failure of responsible parties to meaningfully address documented contradictions.

The author has disclosed his role, interests, and stake in the matters discussed, consistent with ethical journalism standards. Where the conduct of journalists, editors, or media institutions is analyzed, such analysis constitutes protected opinion and critique concerning journalistic method, disclosure, conflicts of interest, and accountability.

This publication is intended to advance transparency, public accountability, and informed civic discourse. Readers are encouraged to review original source materials, request public records, and reach their own conclusions.

AI and Editorial Tools Disclosure

This article was drafted and edited with the assistance of AI-based editorial tools used solely for organization, clarity, structure, and formatting. All factual assertions, interpretations, conclusions, and editorial judgments are those of the author alone. The use of AI tools does not replace independent verification, document review, or human editorial control.

Right of Reply

Individuals and institutions discussed in this article are invited to respond. Substantive responses will be reviewed for possible publication, subject to verification, relevance, and editorial standards. Nonresponsive statements, personal attacks, or unsupported denials will not be published as rebuttal.

Notice Regarding Litigation

The author notes that certain editorial choices by others, including the omission of his name from prior coverage, bear directly on whether disputes remain within the realm of journalism or enter the realm of litigation. This article should not be construed as a waiver of any rights, claims, or remedies available under law.