What a $125 Million Payroll Leaves Behind

A County Budget Stripped to the Bone

By Aaron Knapp

Investigative Journalist

Founder and Editor, Unplugged with Knapp

Knapp Unplugged Media LLC

Editor’s Note: A quick clarification before this turns into bad math and worse assumptions

The $125,299,193.69 payroll figure being discussed here is not an estimate, a projection, or a “rage number.” It comes directly from the county’s own public record titled Lorain County Employees 2025 Salaries, dated January 29, 2026. It lists every individual paid by Lorain County during 2025, line by line, with department, classification, and gross pay, and it totals the amount at the bottom of the report G PETTY REQUEST 2025 LC EMP (1).

A few important points before people start dividing numbers that do not belong together.

First, this document is not a list of identical full-time employees. It includes full-time staff, part-time staff, seasonal workers, grant-funded positions, court personnel, election workers, and individuals who worked only a portion of the year. Some entries are a few hundred dollars. Others are six figures. That is why dividing the total payroll by a census headcount produces a meaningless average. Census employment estimates are snapshots in time. Payroll records count every person paid at any point during the year.

Second, this figure reflects gross pay only. It does not include the county’s employer costs for OPERS retirement contributions, health insurance, Medicare taxes, or other benefits required by law. Those costs exist. They are real. They are simply not captured in this document. The true cost of county employment is higher than $125 million, not lower.

Third, citing “national averages” for individual positions misses the point. The issue is not whether a salary is defensible in isolation. The issue is whether the total payroll structure is sustainable and accountable in a county where per-capita income is roughly $26,000, services are being reduced, and offices are now closing due to budget constraints.

This is not about attacking workers. It is about understanding where public money actually goes. The context is not missing. The context is the document itself. Anyone is free to review it, analyze it, and disagree with conclusions using the same record.

That is how transparency works.

For months, Lorain County delayed the release of its full 2025 employee payroll. The records were formally requested. The obligation to produce them was clear. What followed instead was a prolonged period of silence, partial explanations, and procedural drift that kept the County’s single largest recurring expense out of public view.

The reasons offered were familiar. Staffing constraints. Processing backlogs. Time. None of those explanations altered the underlying reality that, while the records were delayed, the County continued to spend, budget, and govern without public access to the most basic document needed to evaluate those decisions.

Now the records are here.

What they reveal is not a sudden shock. It is confirmation of a trajectory that was already visible, already documented, and already warned about.

The newly released payroll document titled Lorain County Employees 2025 Salaries, dated January 29, 2026, lists every Lorain County employee, their department, their classification, and their gross pay for the year. The total payroll reflected in the document is $125,299,193.69. That number is not an estimate, a projection, or an outside calculation. It is the sum printed directly in the County’s own payroll report.

This figure does not exist in a vacuum. It represents the first and largest claim on the County’s resources, taken before any discussion of what remains.

In 2024, The Payroll That Ate the Budget documented how Lorain County’s payroll growth had begun to outpace revenue growth, quietly reshaping spending priorities and consuming financial flexibility before the public was fully aware of the scale involved. That reporting was not written in hindsight. It was written as a warning. It asked what happens when payroll becomes structurally untethered from long-term planning and treated as an inevitability rather than a policy choice.

The answer is no longer theoretical. It is now printed in the record.

What the County Finally Released

The payroll document produced by Lorain County is comprehensive rather than curated. It does not isolate a single department or employment category. It lists elected officials, appointed officials, full-time employees, part-time workers, levy-funded positions, grant-funded roles, and special classifications spanning every major operational arm of county government. The scope of the document makes clear that this is not a partial snapshot. It is the County’s full employment ledger for the year.

Within that record, clear compensation patterns emerge. Personnel within the Sheriff’s Office account for a significant share of the highest earners, with multiple employees listed above $100,000 in gross pay. That group includes jail facility staff receiving premium percentage classifications as well as specialized and supervisory roles. The Prosecutor’s Office similarly reflects multiple six-figure salaries, encompassing senior staff and officials whose compensation places them among the County’s top earners.

Other departments appear consistently throughout the upper tiers of the payroll as well. Children Services, MRDD, District Health, and the Common Pleas Court system all show recurring high-compensation entries, underscoring that elevated payroll costs are not confined to a single function but distributed across core service and administrative structures.

The County Commissioners themselves are listed as officers with six-figure compensation. The payroll reflects Commissioner David J. Moore with gross pay of $102,043 Riddell, Jeffrey F. Commissioners

County Payroll Report

Gross Pay: $102,043.00 and Commissioner Martin F. Gallagher with gross pay of $101,763.43, figures taken directly from the County’s own payroll report.

None of this information is concealed. None of it requires inference or reconstruction. Every figure is printed plainly in the County’s own report, exactly as the County chose to record and release it. The picture it presents is not selective. It shows the County as it is built to operate, with costs that must be carried before anything else is considered.

SEE PDF Files of ALL Payroll Here (1)

SEE PDF Files of ALL Payroll Here

The Number That Matters Most

The most consequential figure in the payroll document is not any individual salary, title, or department line. It is the aggregate total. It is the number that governs everything else.

$125.3 million in payroll for a single year.

That figure exists independently of narrative. It does not require justification to have effect. It does not depend on whether any one salary can be defended in isolation, whether a role is necessary, or whether a department performs valuable work. Payroll at this scale operates as a structural fact, not a political argument.

Once a county commits itself to a payroll obligation of this magnitude, that commitment becomes the first claim on available resources. It sets the baseline before a single dollar is allocated to capital improvements, before infrastructure needs are evaluated, before reserves are replenished, and before new initiatives are even contemplated. Everything else becomes conditional on what remains after payroll is satisfied.

This is where payroll stops being a line item and becomes a governing constraint.

At $125.3 million, payroll does not merely reflect past decisions. It locks in future ones. It strips flexibility from the budget and leaves little margin for error. The County’s ability to absorb unexpected costs, respond to economic downturns, or course-correct after miscalculations narrows as more of the budget is committed before deliberation begins.

That reality reshapes priorities quietly. Discussions about services become discussions about sustainability rather than expansion. Capital projects are evaluated not on merit alone but on whether they can coexist with fixed personnel costs. Tax policy debates are framed less around what the County wants to do and more around what it must do to maintain existing obligations.

This is not a critique of public employment. It is a recognition of arithmetic.

When payroll consumes this much of a county’s operating reality, it becomes the lens through which all other fiscal questions must be viewed. Transparency does not change that fact. Disclosure does not undo it. But without disclosure, the public cannot see clearly what has already been taken and what is left on the bone.

That was the warning embedded in the earlier reporting. Payroll growth, once it crossed a certain threshold, would cease to be merely a trend and would instead become a condition.

This payroll record confirms that the threshold has been crossed.

The number is no longer abstract. It is no longer projected. It is no longer hypothetical.

It is printed in the County’s own record, and it defines the space in which every future decision will be made.

What Kathryn Kennedy Warned About Before the Numbers Were Public

Long before Lorain County released its full 2025 payroll, the structural consequences now visible in the record had already been identified. Not in hindsight. Not after the fact. But prospectively, in real time, by Kathryn Kennedy.

Across the Kennedy Report series, Kennedy documented a pattern that did not depend on access to internal payroll spreadsheets or delayed disclosures. Her analysis focused instead on budget structure, revenue assumptions, one-time funding decisions, and the quiet expansion of recurring obligations. She warned that Lorain County was constructing a fiscal framework that relied on optimism rather than margin, and on deferral rather than discipline.

That analysis began taking clear shape in The Kennedy Report 2, where early warning signs were tied to budget mechanics rather than political messaging.

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/kennedy-report-2/

In The Kennedy Report 3, the warning sharpened. Kennedy described how one-time money was being used to justify permanent commitments, how payroll expansion was treated as a political achievement rather than a structural liability, and how budget narratives emphasized balance while obscuring the erosion of long-term flexibility. She described this dynamic as a financial illusion not because numbers were fabricated, but because they were incomplete.

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/the-kennedy-report-3/

What the County did not disclose at that time is what the payroll record now discloses plainly.

A county carrying more than $125 million in annual payroll obligation cannot rely indefinitely on temporary revenue, optimistic projections, or political framing to absorb error. Kennedy warned that this approach would eventually force hard choices not because of a sudden crisis, but because of arithmetic. The County would reach a point where payroll alone would define what was possible and what was not.

Kathryn Kennedy

That point has now been reached.

In The Kennedy Report 4, Kennedy’s analysis extended beyond budgeting into governance behavior. She tied fiscal posture to decision-making culture, documenting how confidence replaced caution, certainty substituted for verification, and structural risk was repeatedly reframed as manageable inconvenience. The warning was not that collapse was inevitable, but that exposure was cumulative. Each year payroll grew without corresponding long-term planning reduced the County’s ability to absorb shock elsewhere.

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/the-kennedy-report-4/

The 2025 payroll record confirms that assessment with precision.

The County’s largest recurring cost is no longer inferred. It is documented. And it sits exactly where Kennedy’s analysis indicated it would. Dominant. Inflexible. Defining.

This is not a matter of agreement or disagreement. It is a matter of sequence. The Kennedy Reports laid out the conditions under which Lorain County would eventually confront its own commitments. The payroll disclosure marks the moment when those conditions became unavoidable.

What is most striking when the Kennedy analysis is read alongside the payroll record is how little the outcome depended on any single decision. Kennedy did not argue that one hire, one contract, or one department caused the problem. She documented a pattern in which each choice appeared manageable in isolation but collectively narrowed the County’s margin for error.

The payroll number now gives that pattern scale.

The value of the Kennedy Reports lies not in prediction for its own sake, but in documentation that allows the public to understand how present constraints were built deliberately, incrementally, and openly, even if they were not fully acknowledged at the time. The payroll record does not contradict that work. It completes it.

This is what accountability looks like when analysis precedes disclosure.

The warning was issued before the ledger was visible. The ledger now confirms the warning. And the County must now govern within the reality that both reveal.

Patterns, Not Isolated Paychecks

What the payroll record reveals is not a problem of individual excess or a handful of anomalous salaries. It reveals structure. It shows how Lorain County has organized itself to function, how responsibility has been layered, and how cost accumulates when those layers become permanent rather than provisional.

Across departments, the payroll reflects multiple tiers of administration, specialized classifications, and overlapping functional roles that, taken together, carry substantial cumulative cost. There are numerous part-time employees earning modest wages, positions that in isolation appear unremarkable and necessary to daily operations. At the same time, there is a dense concentration of mid-range salaries, particularly between $60,000 and $90,000, forming the backbone of the County’s operational workforce. These positions are not aberrations. They are the structural middle that sustains the system.

Above that middle tier, the pattern becomes more consequential. Six-figure compensation appears repeatedly and predictably across law enforcement, prosecution, the courts, and human services. These salaries are not confined to a single department or justified by a single function. They recur across systems that are foundational to County operations, indicating that high compensation is embedded in the way authority, expertise, and supervision are distributed.

This is why the payroll should not be read as a scandal spreadsheet. It does not point to one decision gone wrong or one individual paid out of proportion. It functions instead as a governance snapshot. It captures how the County has chosen to build capacity, how it has institutionalized expertise, and how it has translated policy priorities into permanent financial commitments.

When viewed this way, the payroll becomes a map rather than a list. It shows what the County values enough to sustain year after year. It shows which functions are insulated from reduction and which costs are effectively fixed. And it shows how incremental decisions, made over time and often justified individually, have combined to create a system whose cost is now both predictable and inflexible.

This is not about outrage. It is about understanding. The payroll record explains how Lorain County operates, what it has prioritized, and what it must now carry forward. Year after year, budget after budget, those structural choices define the boundaries within which every future decision must be made.

Why the Delay Matters

The delay in releasing Lorain County’s payroll records is not a procedural footnote. It is a substantive part of the story. Timing determines accountability, and when disclosure is postponed, accountability is weakened even if the records are eventually produced.

Public payroll records are not discretionary documents. They are foundational to the public’s ability to evaluate governance in real time. Payroll is the County’s largest recurring obligation, and access to that information is essential for understanding budget proposals, assessing policy tradeoffs, and judging whether public assurances align with fiscal reality. When those records are delayed, the public is asked to evaluate decisions without the very data needed to do so meaningfully.

Delay reduces relevance. It dulls urgency. It pushes consequences beyond the window in which they might influence decision making. By the time the payroll becomes fully visible, budgets have already been adopted, contracts approved, staffing levels fixed, and structural choices effectively locked in. The opportunity for informed debate has passed, replaced by after-the-fact recognition.

This is not an abstract concern. Fiscal decisions are time sensitive. Once adopted, they carry momentum and legal weight. Payroll commitments are not easily reversed, and transparency that arrives after those commitments are cemented cannot alter them. It can only explain them.

That distinction matters.

Transparency after the fact is not transparency in the functional sense. It does not enable oversight. It documents outcomes. It allows the public to see what happened, but not to participate in shaping what happens next. When disclosure is delayed, transparency becomes archival rather than corrective.

The payroll record now provides clarity. But it arrives after key moments for intervention have already passed. That reality does not erase the value of disclosure, but it does underscore why timing is inseparable from accountability. In public finance, when transparency arrives late, its power is diminished, and the cost of decisions has already been transferred forward.

What This Confirms

The payroll record confirms that the concerns raised earlier were not speculative. They were directional. They did not predict a single outcome or allege misconduct. They identified a trajectory. A set of choices moving consistently in one direction, with consequences that would eventually become unavoidable once the full scale of commitment was visible.

That scale is now visible.

Lorain County’s payroll is not simply large in absolute terms. It is structurally dominant. It functions as the primary constraint around which every other financial and policy decision must now be organized. At this level, payroll is no longer a flexible variable. It is a fixed condition that shapes what can be funded, what can be deferred, and what risks can realistically be absorbed.

Once payroll reaches this scale, meaningful reduction becomes exponentially more difficult. Any attempt to reverse course carries immediate and tangible consequences, including service disruption, labor conflict, or political fallout. Those realities are not hypothetical. They are inherent in the structure of public employment. Fixed personnel costs do not unwind gradually. They resist change by design.

This is why the warning mattered when it was issued. And this is why confirmation matters now.

The payroll record does not accuse. It clarifies. It shows that earlier concerns were not exaggerated responses to isolated decisions, but accurate readings of a system moving toward rigidity. What once appeared manageable in isolation has combined into a governing reality that limits options rather than expanding them.

That reality does not assign blame. It assigns responsibility. Responsibility to acknowledge the structure that now exists. Responsibility to govern within it honestly. Responsibility to recognize that future decisions will be constrained not by rhetoric, but by commitments already made.

The Question That Follows the Record

The question raised by this payroll record is not who is paid too much. It is not an exercise in singling out individuals or ranking salaries. The record points instead to a more fundamental issue. Whether Lorain County has constructed a compensation structure that can be sustained without compromising other obligations to the public it serves.

At this scale, payroll is not merely an internal management issue. It is a public policy choice with long-term consequences. Every dollar committed to fixed personnel costs is a dollar that cannot be redeployed easily to infrastructure, capital maintenance, service expansion, or fiscal resilience. The question, then, is not whether the County values its workforce, but whether it has preserved sufficient flexibility to meet competing public needs over time.

That question does not belong to one official or one department. It does not attach neatly to a single vote, contract, or administration. It belongs to the system as a whole. It reflects years of incremental decisions that, taken individually, may have seemed reasonable, but collectively have defined the boundaries within which the County must now operate.

The payroll record makes those boundaries visible.

For the first time, the public can see the full scale of the County’s largest recurring obligation in one place, unfiltered and complete. With that visibility comes the ability to ask harder questions. Not driven by suspicion or outrage, but by evidence. Not framed by rhetoric, but by record.

The document does not answer those questions on its own. It does something more important. It allows them to be asked honestly.

And once asked honestly, they cannot be set aside.

The Five-Year Spiral Comes Into Focus

The significance of this payroll record is not limited to wages and titles. It becomes fully legible only when placed alongside the County’s recent history of financial exposure and governance failure.

Midway Mall and the Cost of Certainty documented how Lorain County converted public funds into speculative redevelopment exposure while treating confidence as a substitute for enforceable safeguards. That decision did not stand alone. It reflected a broader pattern in which institutional certainty preceded verification, and where downside risk was acknowledged only after it had already materialized.

The same pattern reappeared in the County’s handling of its radio communications system.

The CCI lawsuit series traced how secrecy, mismanagement, and internal contradiction brought Lorain County to the brink of a public safety communications collapse. In The CCI Lawsuit: How Secrecy and Mismanagement Brought Lorain County to the Brink, the County’s own filings and conduct revealed a system operating without transparency while insisting on public trust. In The Contradictor-in-Chief: Dave Moore’s 8/15 Performance and the Unraveling of the CCI Sabotage Narrative, that insistence collapsed under the weight of the record itself. In A Filing the Lorain County Commissioners Did Not Want the Public to Read, the paper trail made clear that the County’s public posture diverged sharply from what it was prepared to acknowledge in court.

Those stories examined discrete controversies. Midway Mall. Radio communications. Litigation exposure. Public statements versus sworn filings.

This payroll record connects them.

A County operating with more than $125 million in annual payroll obligation does not have the luxury of serial miscalculation. Payroll at this scale reduces margin for error. It magnifies the consequences of bad bets, delayed disclosures, and confidence-driven decision making. When payroll becomes structurally dominant, every misstep compounds faster and recovers slower.

That is the throughline.

The payroll did not cause the Midway Mall exposure. It did not create the CCI conflict. It did not write the filings that later contradicted public narratives. But it explains why those failures matter more, last longer, and cost more than they otherwise would have.

This is not a story about individual employees. It is not a condemnation of public service. It is a documentation of scale, structure, and consequence.

Taken together, the Midway Mall redevelopment, the radio system conflict, the litigation record, and now the fully disclosed payroll form a single arc. A five-year spiral in which certainty repeatedly replaced caution, transparency followed conflict instead of preceding it, and structural cost quietly narrowed the County’s ability to absorb error.

The payroll after the warning does not introduce a new controversy.

It confirms that the warning was warranted.

And it makes clear that the next set of decisions will be made with far less room to maneuver than the last.

Lorain County Payroll Overview

Highest Earners Based on 2025 Salary Records

What follows is a county-only accounting drawn directly from the Lorain County payroll records dated January 29, 2026, as reflected in the documents you provided. This is not an estimate, not a projection, and not a narrative summary. These are gross pay figures recorded by the County itself. No City of Lorain employees are included here, and no roles outside Lorain County government appear in this list.

I am separating this into two sections. First are all individuals whose recorded gross pay exceeds $100,000. Second is a Top 20 earners list, ordered by gross pay where the data clearly supports ranking. Where ties or close clustering exist, that is noted.

Lorain County Employees Earning Over $100,000

The single highest paid individual in the 2025 Lorain County payroll is Frank P. Miller, Coroner, whose gross pay is recorded at $191,727.50. This figure stands well above the rest of the payroll and represents the highest compensation reflected in the dataset.

Next is Kenneth P. Carney, Engineer-Official, with recorded gross pay of $131,516.00. Closely following is Joshua A. Croston, Sheriff’s Office employee with a 13 percent designation, whose gross pay is listed at $131,280.95.

Christina M. Turcola, Children’s Services, appears next with gross pay of $129,323.36, placing her firmly in the upper tier of county compensation. Joanne Ferritto, District Health, earned $133,927.20, exceeding even that level and ranking among the very highest non-elected compensation lines.

Lisa A. Reed, MRDD Full-Time Employees, is recorded at $118,970.38, while Gregory T. Putka, District Health, earned $118,243.99.

Stacie L. Starr, MRDD Full-Time Employees, appears at $100,954.50, just over the six-figure threshold. Nancy L. Iorillo, Sheriff Jail Facility with a 10 percent designation, earned $101,464.62.

Jason J. Grant, Sheriff Jail Facility 10 percent, is listed at $101,165.68, while Preethi R. Kishman, Prosecutor IVD Program, earned $104,953.40.

Jose F. Gracia, Engineer Road Labor, is recorded at $105,691.21. Jean E. Nazario, Sheriff Jail Facility 10 percent, earned $105,657.27, and William A. Westgate, MRDD Full-Time Employees, appears at $105,930.30.

Finally, Anna M. Tyson, Children’s Services, is recorded at $106,720.13.

These individuals represent every Lorain County employee whose gross pay exceeded $100,000 in the 2025 payroll data provided. This group alone illustrates how six-figure compensation is no longer isolated to a single office or role within the County.

Top 20 Earners in Lorain County by Gross Pay

When the payroll is ranked from highest downward, the Top 20 earners are dominated by leadership, engineering, public safety, health, and services roles.

At the top is Frank P. Miller, Coroner, at $191,727.50.

Second is Joanne Ferritto, District Health, at $133,927.20.

Third is Kenneth P. Carney, Engineer-Official, at $131,516.00.

Fourth is Joshua A. Croston, Sheriff employee 13 percent, at $131,280.95.

Fifth is Christina M. Turcola, Children’s Services, at $129,323.36.

Sixth is Lisa A. Reed, MRDD Full-Time Employees, at $118,970.38.

Seventh is Gregory T. Putka, District Health, at $118,243.99.

Eighth is Anna M. Tyson, Children’s Services, at $106,720.13.

Ninth is William A. Westgate, MRDD Full-Time Employees, at $105,930.30.

Tenth is Jose F. Gracia, Engineer Road Labor, at $105,691.21.

Eleventh is Jean E. Nazario, Sheriff Jail Facility 10 percent, at $105,657.27.

Twelfth is Preethi R. Kishman, Prosecutor IVD Program, at $104,953.40.

Thirteenth is Nancy L. Iorillo, Sheriff Jail Facility 10 percent, at $101,464.62.

Fourteenth is Jason J. Grant, Sheriff Jail Facility 10 percent, at $101,165.68.

Fifteenth is Stacie L. Starr, MRDD Full-Time Employees, at $100,954.50.

The remaining top earners just below the six-figure mark include Gary R. Croston, Todd A. Weegmann, Gerald E. Engineer personnel, and multiple Sheriff and District Health roles clustered in the mid- to high-$90,000 range, showing a dense compensation tier immediately below the six-figure threshold.

Final Thought

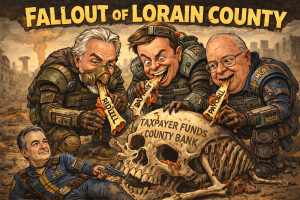

This Is Not a Show. There Is No Reset Button.

Fallout works on television because consequences are optional. When the numbers do not add up, the plot bends. When the vault opens and the shelves are bare, the next episode delivers a twist, a hidden cache, or a miracle stash of caps that somehow makes everything work again. The audience is entertained because scarcity is temporary and accountability is fictional.

Lorain County does not get that luxury.

There is no writers’ room where payroll overruns can be rewritten as heroic inevitability. There is no season finale that allows the ledger to be reconciled by surprise revenue, a forgotten safe, or a deus ex machina buried beneath concrete. The County’s finances operate under arithmetic, not narrative.

When expenditures outpace revenue, when compensation commitments harden into structural obligations, and when warnings are documented and ignored, the result is not suspense. It is fallout.

Aaron Knapp

The numbers were not hidden. The warnings were not vague. Retired CPA, turned “auditor”, Kathryn Kennedy did not speak in metaphors or hypotheticals. She spoke in figures, in trends, in balance sheets that showed payroll growth accelerating faster than sustainable revenue. Those warnings did not come after collapse. They came before it. That distinction matters, because it separates misfortune from decision making.

What followed was not an accident. The County Commissioners are classified as officers. They receive six figure compensation. They approve budgets, classifications, and compensation structures that shape the County’s financial reality. The payroll reflects Commissioner David J. Moore at $102,043, Commissioner Jeffrey F. Riddell at $102,043, and Commissioner Martin F. Gallagher at $101,763.43. Those figures are not symbolic. They are entries in the County’s own ledger. The Sheriff operates within that same ecosystem, funded by the same appropriations, governed by the same fiscal choices.

This is why the Fallout imagery resonates. Not because it is exaggerated, but because it captures the illusion that institutions sometimes cling to. The illusion that tomorrow will fix what today refuses to confront. The illusion that there will always be another vault, another reserve, another workaround that allows hard choices to be deferred without consequence.

But this is the real world. When taxpayer funds are committed, they are not props. When payroll grows, it does not reset at the end of the episode. When warnings are ignored, they do not disappear. They compound.

The fallout here is not fictional ruin. It is diminished flexibility, constrained services, and a County boxed in by decisions that were made openly, documented clearly, and approved anyway. Accountability does not require villains. It requires memory. It requires refusing to pretend that this was unforeseeable, unavoidable, or accidental.

Fallout is entertainment because it lets us escape reality. This story matters because it does the opposite.

Aaron Knapp, LSW,BSSW

Why This Matters

This list shows, in black-and-white numbers, that Lorain County payroll concentration is not anecdotal. It is documented, repeatable, and structural. Six-figure compensation is spread across departments rather than isolated, and the clustering just below $100,000 suggests a payroll ceiling that has effectively become a soft floor.

Related Reporting and Prior Warnings

This payroll disclosure does not stand alone. It completes and corroborates a body of reporting that has examined the City of Lorain’s financial posture, internal budgeting habits, and exposure to cumulative fiscal risk over multiple budget cycles. Rather than emerging suddenly or without warning, the figures now reflected in the payroll record align with trends that were visible in the City’s own data well before the full 2025 payroll was compiled and released.

The most direct antecedent to this disclosure is The Payroll That Ate the Budget, which documented how the City of Lorain’s personnel costs were increasing at a pace that outstripped revenue growth and quietly reshaped spending priorities long before the current payroll totals became public. That reporting treated payroll not as a series of discrete salaries or isolated compensation decisions, but as a structural driver of fiscal constraint, demonstrating how rising personnel costs recalibrated the City’s budgetary baseline year after year. The warning embedded in that analysis is now borne out by the City’s own payroll ledger, which confirms that the growth identified earlier was neither hypothetical nor temporary, but embedded in the City’s operating reality.

The Payroll That Ate the Budget

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-payroll-that-ate-the-budget/

That payroll analysis sits within a broader financial narrative examined in the Financial Illusion series, which traced how one-time funding, optimistic assumptions, and political framing combined to create the appearance of stability while embedding long-term obligations into the County’s operating structure.

Lorain County’s Financial Illusion: How One-Time Money, Payroll Expansion, and Political Gamesmanship Created a Manufactured Crisis

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/state-government-ohio/county-of-lorain/lorain-countys-financial-illusion-how-one-time-money-payroll-expansion-and-political-gamesmanship-created-a-manufactured-crisis/

That analysis continued in a second installment examining what those structural choices meant going forward once temporary revenue disappeared and recurring costs remained.

Lorain County’s Financial Illusion, Part Two: What Comes Next and Why It Matters

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/state-government-ohio/county-of-lorain/lorain-countys-financial-illusion-part-two-what-comes-next-and-why-it-matters/

Long before the payroll ledger was made public, Kathryn Kennedy’s reporting identified the same trajectory through budget mechanics rather than delayed disclosures. Her analysis did not rely on insider documents. It relied on structure, sequencing, and arithmetic.

In The Kennedy Report 2, early warning signs were tied to revenue assumptions, expenditure growth, and the increasing reliance on confidence rather than margin.

The Kennedy Report 2

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/kennedy-report-2/

That warning sharpened in The Kennedy Report 3, which described how one-time money was being used to justify permanent commitments and how payroll expansion was treated as a political accomplishment rather than a structural liability.

The Kennedy Report 3

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/the-kennedy-report-3/

In The Kennedy Report 4, the analysis expanded beyond finance into governance behavior, documenting how certainty replaced verification and how cumulative exposure was repeatedly reframed as manageable inconvenience.

The Kennedy Report 4

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/kennedy-reports/the-kennedy-report-4/

Those financial patterns intersect with Lorain County’s broader record of high-risk decision making and delayed accountability, most notably in the Midway Mall redevelopment and the County’s handling of its public safety radio system.

Midway Mall and the Cost of Certainty documented how public funds were converted into speculative redevelopment exposure under conditions of institutional confidence without enforceable safeguards, a pattern that later produced measurable loss.

Midway Mall and the Cost of Certainty

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-warning-that-preceded-the-collapse/

The same governance posture reappeared in the CCI litigation, where secrecy, mismanagement, and internal contradiction pushed the County toward operational and legal crisis.

The CCI Lawsuit: How Secrecy and Mismanagement Brought Lorain County to the Brink

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-cci-lawsuit-how-secrecy-and-mismanagement-brought-lorain-county-to-the-brink/

That narrative further unraveled when public statements collided with sworn filings and internal records.

The Contradictor-in-Chief: Dave Moore’s 8/15 Performance and the Unraveling of the CCI Sabotage Narrative

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/the-contradictor-in-chief-dave-moores-8-15-performance-and-the-unraveling-of-the-cci-sabotage-narrative/

And finally,

A Filing the Lorain County Commissioners Did Not Want the Public to Read

https://aaronknappunplugged.com/news/a-filing-the-lorain-county-commissioners-did-not-want-the-public-to-read/

Together, those stories form a continuous record. The payroll disclosure does not introduce a new controversy. It provides the missing scale that makes the prior warnings fully legible.

Aaron Knapp is an investigative journalist and public-records litigator based in Lorain County, Ohio. His reporting focuses on local government finance, public accountability, records compliance, and the gap between official narrative and documentary record. His work is grounded in primary-source documentation, statutory analysis, and court filings, and is published independently without advertising or institutional sponsorship.

Publisher Information

Unplugged with Knapp is an independent investigative publication operated by Knapp Unplugged Media LLC, an Ohio limited liability company. All reporting is produced without advertising and is supported by readers who value document-driven journalism and public accountability.

Copyright © 2026 Knapp Unplugged Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Legal Disclosure and Scope of Reporting

This article is a work of journalism and commentary protected under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution.

It is not legal advice, not financial advice, and not a substitute for professional counsel. The analysis herein reflects the author’s interpretation of publicly available records, government documents, payroll reports, court filings, and budget materials. Readers should consult qualified professionals for advice specific to their circumstances.

All factual statements are based on documents produced by Lorain County, filings submitted in court, or prior published reporting cited within the article. Allegations referenced from litigation or public controversy remain allegations unless and until adjudicated. Nothing herein should be construed as a finding of criminal, civil, or ethical liability.

Public Records and Source Integrity Disclosure

This reporting relies on public records obtained pursuant to Ohio law, including payroll records, budget documents, and court filings. Quotes, figures, and descriptions are presented as they appear in the source materials unless otherwise noted. Emphasis, contextual framing, and analysis are the work of the author.

Any errors discovered will be corrected promptly and transparently.

Artificial Intelligence and Visual Media Disclosure

Some illustrative images accompanying this article may be AI-generated or digitally enhanced for editorial and illustrative purposes only. AI tools are used solely for visual representation, layout assistance, or image generation and are not used to fabricate facts, alter documents, or generate reporting content.

All written analysis, conclusions, and narrative framing are authored by the journalist. AI tools do not determine editorial judgment.

Editorial Independence Disclosure

This publication accepts no advertising, no government funding, and no political sponsorship. Financial support from readers does not influence editorial decisions, conclusions, or coverage priorities.

Transparency is not hostility. It is the baseline expectation of a system that exercises power over the public.

Independent local journalism exists to do the work that institutions cannot do for themselves.

This investigation is published free and without advertising so that access to information is not conditioned on ability to pay, platform algorithms, or tolerance for distraction. That choice is deliberate. It reflects a belief that public accountability work loses its value the moment it becomes gated, sponsored, or softened to satisfy commercial interests. It is also a choice that carries real cost.

This work requires time, records requests, document review, litigation monitoring, and long-form analysis that cannot be produced on a volunteer basis indefinitely. Filing public records requests is not free. Obtaining transcripts, reviewing filings, preserving evidence, and publishing findings with care and accuracy requires sustained effort and financial support. Doing this work without advertising protects editorial independence, but it removes the revenue streams most media organizations rely upon.

Please consider supporting this reporting.

If this work matters to you, if you believe local government functions best when it is observed rather than trusted blindly, and if you value journalism that documents rather than speculates, your support makes a direct difference. Contributions allow this publication to continue requesting records, reviewing filings, publishing findings, and preserving timelines without pressure to soften conclusions or chase attention.

Transparency is not guaranteed by statute alone. It is guaranteed by people. It is guaranteed by readers who understand that sunlight does not appear automatically, that records do not surface on their own, and that accountability requires sustained, independent effort. When institutions resist scrutiny, the only thing that forces the record into view is persistence backed by public support.

This work remains free because access matters. Its continuation depends on whether the public believes that independent local journalism is worth sustaining.

Legal Disclaimer and Intellectual Property Notice

This illustration and the accompanying article are published as political commentary and journalistic expression concerning Lorain County public finances, payroll data, and governance. The images are expressive works intended to convey criticism, satire, and commentary on matters of public concern. They are protected speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 11 of the Ohio Constitution. No assertion of criminal conduct is made unless explicitly supported by cited public records, filings, or adjudicated findings. All individuals depicted are public officials or public employees whose compensation and roles are matters of public record under Ohio Revised Code 149.43.

This content is not legal advice. It is not a factual assertion that any individual engaged in unlawful activity. It is an opinionated, illustrative commentary based on disclosed payroll figures, public budgets, and governance decisions reflected in official county records. Readers are encouraged to review the underlying source documents directly and to draw their own conclusions.

Fair Use and Parody Notice Regarding Fallout

The imagery used in this work is inspired by the visual language and aesthetic commonly associated with the Fallout video game and television franchise. Fallout is a registered trademark and copyrighted property of Bethesda Softworks LLC, a subsidiary of ZeniMax Media Inc. All trademarks, logos, character styles, and franchise references remain the property of their respective owners.

This work is an unauthorized, noncommercial parody and commentary that makes nominative and transformative use of familiar visual tropes for the purpose of criticism, satire, and public-interest journalism. Such use is protected under the doctrine of fair use pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 107. The illustrations do not claim affiliation with, endorsement by, or sponsorship from Bethesda Softworks, ZeniMax Media, Microsoft, Amazon Studios, or any entity associated with the Fallout franchise.

The use of a post-apocalyptic vault motif is intended as metaphor. Any resemblance to specific proprietary characters such as Vault Boy is stylistic and illustrative, not a claim of origin, authorship, or endorsement.

Attribution and Reference

Fallout® is a registered trademark of Bethesda Softworks LLC

https://bethesda.net

https://fallout.bethesda.net

All rights to the Fallout franchise, including game titles, television adaptations, characters, and related intellectual property, are expressly acknowledged as belonging to Bethesda Softworks LLC and its licensors.

Editorial Independence Statement

This publication operates independently and without advertising. Visual illustrations may incorporate AI-assisted generation as part of the creative process. All factual claims regarding payroll, compensation, titles, and public roles are derived from Lorain County records released pursuant to Ohio public records law. Any illustrative exaggeration is intentional and serves rhetorical and critical purposes only.

Transparency is not hostility. Satire is not defamation. Public accountability reporting necessarily includes uncomfortable facts and expressive critique.

Thank you Miss Kennedy